The Yigu Episode and Its Repercussions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Report

Document of The World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized Report No.: 48966 PROJECT PERFORMANCE ASSESSMENT REPORT Public Disclosure Authorized CHINA TRI-PROVINCIAL HIGHWAY PROJECT (LOAN 4356-CHA) AND HUBEI-XIAOGAN-XIANGFAN HIGHWAY PROJECT (LOAN 4677-CHA) Public Disclosure Authorized June 17, 2009 Public Disclosure Authorized Sector Evaluation Division Independent Evaluation Group (World Bank) Currency Equivalents (annual averages) Currency Unit = Yuan, USD1.00 = 7.32 Y (RMB) 1998 US$1.00 Y 8.28 1999 US$1.00 Y 8.27 2000 US$1.00 Y 8.27 2001 US$1.00 Y 8.27 2002 US$1.00 Y 8.27 2003 US$1.00 Y 8.27 2004 US$1.00 Y 8.27 2005 US$1.00 Y 8.20 2006 US$1.00 Y 7.97 2007 US$1.00 Y 7.50 Abbreviations and Acronyms AA Alternative Analysis ADT Average Daily Traffic BDH Baotou-Dongsheng Highway BDR Baotou-Dongsheng Road BFH Baiyinchagan-Fengzhen Highway CAS Country Assistance Strategy CPS Country Partnership Strategy DPL Development Policy Loan EA Environmental Assessment EAP Environmental Action Plan EIA Environmental Impact Assessment EMP Environmental Management Plan ENPV Economic Net Present Value ERR Economic Rate of Return FIDIC Fédération Internationale des Ingénieurs-Conseils FRR Financial Rate of Return FNPV Financial Net Present Value GNP Gross National Product GOC Government of China GRP Gross Regional Product GOVAI Gross Output Value of Agriculture and Industry GPCD Gansu Provincial Communications Department GWH Guyaozi-Wangquanliang Highway ICR Implementation Completion Report ICB International Competitive Bidding IEGWB Independent Evaluation -

Continuing Crackdown in Inner Mongolia

CONTINUING CRACKDOWN IN INNER MONGOLIA Human Rights Watch/Asia (formerly Asia Watch) CONTINUING CRACKDOWN IN INNER MONGOLIA Human Rights Watch/Asia (formerly Asia Watch) Human Rights Watch New York $$$ Washington $$$ Los Angeles $$$ London Copyright 8 March 1992 by Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. ISBN 1-56432-059-6 Human Rights Watch/Asia (formerly Asia Watch) Human Rights Watch/Asia was established in 1985 to monitor and promote the observance of internationally recognized human rights in Asia. Sidney Jones is the executive director; Mike Jendrzejczyk is the Washington director; Robin Munro is the Hong Kong director; Therese Caouette, Patricia Gossman and Jeannine Guthrie are research associates; Cathy Yai-Wen Lee and Grace Oboma-Layat are associates; Mickey Spiegel is a research consultant. Jack Greenberg is the chair of the advisory committee and Orville Schell is vice chair. HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH Human Rights Watch conducts regular, systematic investigations of human rights abuses in some seventy countries around the world. It addresses the human rights practices of governments of all political stripes, of all geopolitical alignments, and of all ethnic and religious persuasions. In internal wars it documents violations by both governments and rebel groups. Human Rights Watch defends freedom of thought and expression, due process and equal protection of the law; it documents and denounces murders, disappearances, torture, arbitrary imprisonment, exile, censorship and other abuses of internationally recognized human rights. Human Rights Watch began in 1978 with the founding of its Helsinki division. Today, it includes five divisions covering Africa, the Americas, Asia, the Middle East, as well as the signatories of the Helsinki accords. -

Chinacoalchem

ChinaCoalChem Monthly Report Issue May. 2019 Copyright 2019 All Rights Reserved. ChinaCoalChem Issue May. 2019 Table of Contents Insight China ................................................................................................................... 4 To analyze the competitive advantages of various material routes for fuel ethanol from six dimensions .............................................................................................................. 4 Could fuel ethanol meet the demand of 10MT in 2020? 6MTA total capacity is closely promoted ....................................................................................................................... 6 Development of China's polybutene industry ............................................................... 7 Policies & Markets ......................................................................................................... 9 Comprehensive Analysis of the Latest Policy Trends in Fuel Ethanol and Ethanol Gasoline ........................................................................................................................ 9 Companies & Projects ................................................................................................... 9 Baofeng Energy Succeeded in SEC A-Stock Listing ................................................... 9 BG Ordos Started Field Construction of 4bnm3/a SNG Project ................................ 10 Datang Duolun Project Created New Monthly Methanol Output Record in Apr ........ 10 Danhua to Acquire & -

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level Corresponding Type Chinese Court Region Court Name Administrative Name Code Code Area Supreme People’s Court 最高人民法院 最高法 Higher People's Court of 北京市高级人民 Beijing 京 110000 1 Beijing Municipality 法院 Municipality No. 1 Intermediate People's 北京市第一中级 京 01 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Shijingshan Shijingshan District People’s 北京市石景山区 京 0107 110107 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Haidian District of Haidian District People’s 北京市海淀区人 京 0108 110108 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Mentougou Mentougou District People’s 北京市门头沟区 京 0109 110109 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Changping Changping District People’s 北京市昌平区人 京 0114 110114 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Yanqing County People’s 延庆县人民法院 京 0229 110229 Yanqing County 1 Court No. 2 Intermediate People's 北京市第二中级 京 02 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Dongcheng Dongcheng District People’s 北京市东城区人 京 0101 110101 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Xicheng District Xicheng District People’s 北京市西城区人 京 0102 110102 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Fengtai District of Fengtai District People’s 北京市丰台区人 京 0106 110106 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality 1 Fangshan District Fangshan District People’s 北京市房山区人 京 0111 110111 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Daxing District of Daxing District People’s 北京市大兴区人 京 0115 -

CREATING LIVABLE ASIAN CITIES Edited by Bambang Susantono and Robert Guild

CREATING LIVABLE ASIAN CITIES Edited by Bambang Susantono and Robert Guild APRIL ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK Book Endorsements Seung-soo Han Former Prime Minister of the Republic of Korea Creating Livable Asian Cities comes at a timely moment. The book emphasizes innovative technologies that can overcome challenges to make the region’s cities better places to live and grow. Its approach encourages stronger urban institutions focused on all people in every community. The book will inspire policy makers to consider concrete measures that can help cities ‘build back better,’ in other words, to be more resilient and able to withstand the next crisis. In the post-pandemic period, livable Asian cities are a public good, just as green spaces are. Following this credo, however, requires Asia to invest in creating livable cities so they can fulfil their potential as avenues of innovation, prosperity, inclusiveness, and sustainability. In this book, Asian Development Bank experts map the challenges facing cities in the region. Its five priority themes—smart and inclusive planning, sustainable transport, sustainable energy, innovative financing, and resilience and rejuvenation—illuminate a path for urbanization in Asia over the next decade. This book will lead us to the innovative thinking needed to improve urban life across the region. Maimunah Modh Sharif Under-Secretary-General and Executive Director, United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat) Creating Livable Asian Cities addresses various urban development challenges and offers in-depth analysis and rich insights on urban livability in Asia from an urban economics perspective. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) is well-placed to review the investment needs of cities that will contribute to sustainable development. -

Laogai Handbook 劳改手册 2007-2008

L A O G A I HANDBOOK 劳 改 手 册 2007 – 2008 The Laogai Research Foundation Washington, DC 2008 The Laogai Research Foundation, founded in 1992, is a non-profit, tax-exempt organization [501 (c) (3)] incorporated in the District of Columbia, USA. The Foundation’s purpose is to gather information on the Chinese Laogai - the most extensive system of forced labor camps in the world today – and disseminate this information to journalists, human rights activists, government officials and the general public. Directors: Harry Wu, Jeffrey Fiedler, Tienchi Martin-Liao LRF Board: Harry Wu, Jeffrey Fiedler, Tienchi Martin-Liao, Lodi Gyari Laogai Handbook 劳改手册 2007-2008 Copyright © The Laogai Research Foundation (LRF) All Rights Reserved. The Laogai Research Foundation 1109 M St. NW Washington, DC 20005 Tel: (202) 408-8300 / 8301 Fax: (202) 408-8302 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.laogai.org ISBN 978-1-931550-25-3 Published by The Laogai Research Foundation, October 2008 Printed in Hong Kong US $35.00 Our Statement We have no right to forget those deprived of freedom and 我们没有权利忘却劳改营中失去自由及生命的人。 life in the Laogai. 我们在寻求真理, 希望这类残暴及非人道的行为早日 We are seeking the truth, with the hope that such horrible 消除并且永不再现。 and inhumane practices will soon cease to exist and will never recur. 在中国,民主与劳改不可能并存。 In China, democracy and the Laogai are incompatible. THE LAOGAI RESEARCH FOUNDATION Table of Contents Code Page Code Page Preface 前言 ...............................................................…1 23 Shandong Province 山东省.............................................. 377 Introduction 概述 .........................................................…4 24 Shanghai Municipality 上海市 .......................................... 407 Laogai Terms and Abbreviations 25 Shanxi Province 山西省 ................................................... 423 劳改单位及缩写............................................................28 26 Sichuan Province 四川省 ................................................ -

December 1998

JANUARY - DECEMBER 1998 SOURCE OF REPORT DATE PLACE NAME ALLEGED DS EX 2y OTHER INFORMATION CRIME Hubei Daily (?) 16/02/98 04/01/98 Xiangfan C Si Liyong (34 yrs) E 1 Sentenced to death by the Xiangfan City Hubei P Intermediate People’s Court for the embezzlement of 1,700,00 Yuan (US$20,481,9). Yunnan Police news 06/01/98 Chongqing M Zhang Weijin M 1 1 Sentenced by Chongqing No. 1 Intermediate 31/03/98 People’s Court. It was reported that Zhang Sichuan Legal News Weijin murdered his wife’s lover and one of 08/05/98 the lover’s relatives. Shenzhen Legal Daily 07/01/98 Taizhou C Zhang Yu (25 yrs, teacher) M 1 Zhang Yu was convicted of the murder of his 01/01/99 Zhejiang P girlfriend by the Taizhou City Intermediate People’s Court. It was reported that he had planned to kill both himself and his girlfriend but that the police had intervened before he could kill himself. Law Periodical 19/03/98 07/01/98 Harbin C Jing Anyi (52 yrs, retired F 1 He was reported to have defrauded some 2600 Liaoshen Evening News or 08/01/98 Heilongjiang P teacher) people out of 39 million Yuan 16/03/98 (US$4,698,795), in that he loaned money at Police Weekend News high rates of interest (20%-60% per annum). 09/07/98 Southern Daily 09/01/98 08/01/98 Puning C Shen Guangyu D, G 1 1 Convicted of the murder of three children - Guangdong P Lin Leshan (f) M 1 1 reported to have put rat poison in sugar and 8 unnamed Us 8 8 oatmeal and fed it to the three children of a man with whom she had a property dispute. -

August 29 - September 03, 2021

August 29 - September 03, 2021 www.irmmw-thz2021.org 1 PROGRAM PROGRAM MENU FUTURE AND PAST CONFERENCES························ 1 ORGANIZERS·················································· 2 COMMITTEES················································· 3 PLENARY SESSION LIST······································ 8 PRIZES & AWARDS··········································· 10 SCIENTIFIC PROGRAM·······································16 MONDAY···················································16 TUESDAY··················································· 50 WEDNESDAY·············································· 85 THURSDAY··············································· 123 FRIDAY···················································· 167 INFORMATION.. FOR PRESENTERS ORAL PRESENTERS PLENARY TALK 45 min. (40 min. presentation + 5 min. discussion) KEYNOTES COMMUNICATION 30 min. (25 min. presentation + 5 min.discussion) ORAL COMMUNICATION 15 min. (12 min. presentation + 3 min.discussion) Presenters should be present at ZOOM Meeting room 10 minutes before the start of the session and inform the Session Chair of their arrival through the chat window. Presenters test the internet, voice and video in advance. We strongly recommend the External Microphone for a better experience. Presenters will be presenting their work through “Screen share” of their slides. POSTER PRESENTERS Presenters MUST improve the poster display content through exclusive editing links (Including the Cover, PDF file, introduction.) Please do respond in prompt when questions -

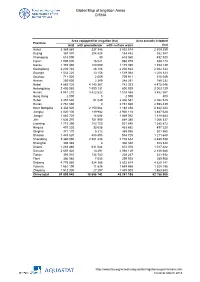

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA Area equipped for irrigation (ha) Area actually irrigated Province total with groundwater with surface water (ha) Anhui 3 369 860 337 346 3 032 514 2 309 259 Beijing 367 870 204 428 163 442 352 387 Chongqing 618 090 30 618 060 432 520 Fujian 1 005 000 16 021 988 979 938 174 Gansu 1 355 480 180 090 1 175 390 1 153 139 Guangdong 2 230 740 28 106 2 202 634 2 042 344 Guangxi 1 532 220 13 156 1 519 064 1 208 323 Guizhou 711 920 2 009 709 911 515 049 Hainan 250 600 2 349 248 251 189 232 Hebei 4 885 720 4 143 367 742 353 4 475 046 Heilongjiang 2 400 060 1 599 131 800 929 2 003 129 Henan 4 941 210 3 422 622 1 518 588 3 862 567 Hong Kong 2 000 0 2 000 800 Hubei 2 457 630 51 049 2 406 581 2 082 525 Hunan 2 761 660 0 2 761 660 2 598 439 Inner Mongolia 3 332 520 2 150 064 1 182 456 2 842 223 Jiangsu 4 020 100 119 982 3 900 118 3 487 628 Jiangxi 1 883 720 14 688 1 869 032 1 818 684 Jilin 1 636 370 751 990 884 380 1 066 337 Liaoning 1 715 390 783 750 931 640 1 385 872 Ningxia 497 220 33 538 463 682 497 220 Qinghai 371 170 5 212 365 958 301 560 Shaanxi 1 443 620 488 895 954 725 1 211 648 Shandong 5 360 090 2 581 448 2 778 642 4 485 538 Shanghai 308 340 0 308 340 308 340 Shanxi 1 283 460 611 084 672 376 1 017 422 Sichuan 2 607 420 13 291 2 594 129 2 140 680 Tianjin 393 010 134 743 258 267 321 932 Tibet 306 980 7 055 299 925 289 908 Xinjiang 4 776 980 924 366 3 852 614 4 629 141 Yunnan 1 561 190 11 635 1 549 555 1 328 186 Zhejiang 1 512 300 27 297 1 485 003 1 463 653 China total 61 899 940 18 658 742 43 241 198 52 -

Metallogeny of Northern, Central and Eastern Asia

METALLOGENY OF NORTHERN, CENTRAL AND EASTERN ASIA Explanatory Note to the Metallogenic map of Northern–Central–Eastern Asia and Adjacent Areas at scale 1:2,500,000 VSEGEI Printing House St. Petersburg • 2017 Abstract Explanatory Notes for the “1:2.5 M Metallogenic Map of Northern, Central, and Eastern Asia” show results of long-term joint research of national geological institutions of Russia, China, Kazakhstan, Mongolia, and the Republic of Korea. The latest published geological materials and results of discussions for Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and North Korea were used as well. Described metallogenic objects: 7,081 mineral deposits, 1,200 ore knots, 650 ore regions and ore zones, 231 metallogenic areas and metallogenic zones, 88 metallogenic provinces. The total area of the map is 30 M km2. Tab. 10, fig. 15, list of ref. 94 items. Editors-in-Chief: O.V. Petrov, A.F. Morozov, E.A. Kiselev, S.P. Shokalsky (Russia), Dong Shuwen (China), O. Chuluun, O. Tomurtogoo (Mongolia), B.S. Uzhkenov, M.A. Sayduakasov (Kazakhstan), Hwang Jae Ha, Kim Bok Chul (Korea) Authors G.A. Shatkov, O.V. Petrov, E.M. Pinsky, N.S. Solovyev, V.P. Feoktistov, V.V. Shatov, L.D. Rucheykova, V.A. Gushchina, A.N. Gureev (Russia); Chen Tingyu, Geng Shufang, Dong Shuwen, Chen Binwei, Huang Dianhao, Song Tianrui, Sheng Jifu, Zhu Guanxiang, Sun Guiying, Yan Keming, Min Longrui, Jin Ruogu, Liu Ping, Fan Benxian, Ju Yuanjing, Wang Zhenyang, Han Kunying, Wang Liya (China); Dezhidmaa G., Tomurtogoo O. (Mongolia); Bok Chul Kim, Hwang Jae Ha (Republic of Korea); B.S. Uzhkenov, A.L. -

CHINA HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2007/08 Access for All: Basic Public Services for 1.3 Billion People

CHINA HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2007/08 Access for all: Basic public services for 1.3 billion people The preparation of this report was commissioned by UNDP China and coordinated by the China Institute for Reform and Development China Publishing Group Corporation China Translation & Publishing Corporation CIP Data &KLQD+XPDQ'HYHORSPHQW5HSRUW%DVLF3XEOLF6HUYLFHV%HQH¿WLQJ%LOOLRQ&KLQHVH 3HRSOH(QJOLVK &RPSLOHGE\8QLWHG1DWLRQV'HYHORSPHQW3URJUDP±%HLMLQJ&KLQD7UDQVODWLRQDQG3XEOLVKLQJ &RUSRUDWLRQ1RYHPEHU,6%1 ,&KLQD«,,8QLWHG«,,,6RFLDOGHYHORSPHQW±5HVHDUFKUHSRUW±&KLQD²a²(QJOLVK 6RFLDOVHUYLFH²5HVHDUFKUHSRUW²&KLQD²a²(QJOLVK,9' $UFKLYDO/LEUDU\RI&KLQHVH3XEOLFDWLRQV&,3'DWD+= 1R All rights reserved. Any part of this publication may be quoted, copied, or translated by indicating the source. No part of this publication may be stored for commercial purposes without prior written permission. 7KHSXEOLFDWLRQRQO\UHÀHFWVWKHRSLQLRQVRIWKHZULWHUVEXWQRWQHFHVVDULO\WKH8QLWHG 1DWLRQVRU8QLWHG1DWLRQV'HYHORSPHQW3URJUDPPH7KHIRUPDQGFRQWHQWRIDQ\PDS LQFOXGHGLQWKHSXEOLFDWLRQGRHVQRWUHSUHVHQWRULQGLFDWHWKHOHJDOVWDWXVDQGULJKWRI81 6HFUHWDULDWRU81'3WRDQ\FRXQWU\UHJLRQFLW\RUDUHDRUWKHSRVLWLRQDQGYLHZSRLQWWR the territory and boundary. 3XEOLVKHGE\&KLQD7UDQVODWLRQDQG3XEOLVKLQJ&RUSRUDWLRQ $GGUHVV)ORRU:XKXD%XLOGLQJ $ &KHJRQJ]KXDQJ6WUHHW ;LFKHQJ'LVWULFW%HLMLQJ&KLQD 7HO Email: [email protected] :HEVLWHhttp://www.ctpc.com.cn &RYHU'HVLJQ6SHQFH//& /D\RXW'HVLJQ6SHQFH//& Distributor: Xinhua Bookstore )RUPDWîPP (GLWLRQ1RYHPEHU¿UVWHGLWLRQ 3ULQWLQJ1RYHPEHU¿UVWSULQWLQJ ,6%13ULFH50% $OOULJKWUHVHUYHG &KLQD7UDQVODWLRQDQG3XEOLVKLQJ&RUSRUDWLRQ -

Human Brucellosis Occurrences in Inner Mongolia, China: a Spatio-Temporal Distribution and Ecological Niche Modeling Approach Peng Jia1* and Andrew Joyner2

Jia and Joyner BMC Infectious Diseases (2015) 15:36 DOI 10.1186/s12879-015-0763-9 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Human brucellosis occurrences in inner mongolia, China: a spatio-temporal distribution and ecological niche modeling approach Peng Jia1* and Andrew Joyner2 Abstract Background: Brucellosis is a common zoonotic disease and remains a major burden in both human and domesticated animal populations worldwide. Few geographic studies of human Brucellosis have been conducted, especially in China. Inner Mongolia of China is considered an appropriate area for the study of human Brucellosis due to its provision of a suitable environment for animals most responsible for human Brucellosis outbreaks. Methods: The aggregated numbers of human Brucellosis cases from 1951 to 2005 at the municipality level, and the yearly numbers and incidence rates of human Brucellosis cases from 2006 to 2010 at the county level were collected. Geographic Information Systems (GIS), remote sensing (RS) and ecological niche modeling (ENM) were integrated to study the distribution of human Brucellosis cases over 1951–2010. Results: Results indicate that areas of central and eastern Inner Mongolia provide a long-term suitable environment where human Brucellosis outbreaks have occurred and can be expected to persist. Other areas of northeast China and central Mongolia also contain similar environments. Conclusions: This study is the first to combine advanced spatial statistical analysis with environmental modeling techniques when examining human Brucellosis outbreaks and will help to inform decision-making in the field of public health. Keywords: Brucellosis, Geographic information systems, Remote sensing technology, Ecological niche modeling, Spatial analysis, Inner Mongolia, China, Mongolia Background through the consumption of unpasteurized dairy products Brucellosis, a common zoonotic disease also referred to [4].