Mats, P. Vii, 1, 13–16

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book I. Title XXVII. Concerning the Office of the Praetor Prefect Of

Book I. Title XXVII. Concerning the office of the Praetor Prefect of Africa and concerning the whole organization of that diocese. (De officio praefecti praetorio Africae et de omni eiusdem dioeceseos statu.) Headnote. Preliminary. For a better understanding of the following chapters in the Code, a brief outline of the organization of the Roman Empire may be given, but historical works will have to be consulted for greater details. The organization as contemplated in the Code was the one initiated by Diocletian and Constantine the Great in the latter part of the third and the beginning of the fourth century of the Christian era, and little need be said about the time previous to that. During the Republican period, Rome was governed mainly by two consuls, tow or more praetors (C. 1.39 and note), quaestors (financial officers and not to be confused with the imperial quaestor of the later period, mentioned at C. 1.30), aediles and a prefect of food supply. The provinces were governed by ex-consuls and ex- praetors sent to them by the Senate, and these governors, so sent, had their retinue of course. After the empire was established, the provinces were, for a time, divided into senatorial and imperial, the later consisting mainly of those in which an army was required. The senate continued to send out ex-consuls and ex-praetors, all called proconsuls, into the senatorial provinces. The proconsul was accompanied by a quaestor, who was a financial officer, and looked after the collection of the revenue, but who seems to have been largely subservient to the proconsul. -

RICE, CARL ROSS. Diocletian's “Great

ABSTRACT RICE, CARL ROSS. Diocletian’s “Great Persecutions”: Minority Religions and the Roman Tetrarchy. (Under the direction of Prof. S. Thomas Parker) In the year 303, the Roman Emperor Diocletian and the other members of the Tetrarchy launched a series of persecutions against Christians that is remembered as the most severe, widespread, and systematic persecution in the Church’s history. Around that time, the Tetrarchy also issued a rescript to the Pronconsul of Africa ordering similar persecutory actions against a religious group known as the Manichaeans. At first glance, the Tetrarchy’s actions appear to be the result of tensions between traditional classical paganism and religious groups that were not part of that system. However, when the status of Jewish populations in the Empire is examined, it becomes apparent that the Tetrarchy only persecuted Christians and Manichaeans. This thesis explores the relationship between the Tetrarchy and each of these three minority groups as it attempts to understand the Tetrarchy’s policies towards minority religions. In doing so, this thesis will discuss the relationship between the Roman state and minority religious groups in the era just before the Empire’s formal conversion to Christianity. It is only around certain moments in the various religions’ relationships with the state that the Tetrarchs order violence. Consequently, I argue that violence towards minority religions was a means by which the Roman state policed boundaries around its conceptions of Roman identity. © Copyright 2016 Carl Ross Rice All Rights Reserved Diocletian’s “Great Persecutions”: Minority Religions and the Roman Tetrarchy by Carl Ross Rice A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of North Carolina State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts History Raleigh, North Carolina 2016 APPROVED BY: ______________________________ _______________________________ S. -

Ius Militare – Military Courts in the Roman Law (I)

International Journal of Sciences: Basic and Applied Research (IJSBAR) ISSN 2307-4531 (Print & Online) http://gssrr.org/index.php?journal=JournalOfBasicAndApplied --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Ius Militare – Military Courts in the Roman Law (I) PhD Dimitar Apasieva*, PhD Olga Koshevaliskab a,bGoce Delcev University – Shtip, Shtip 2000, Republic of Macedonia aEmail: [email protected] bEmail: [email protected] Abstract Military courts in ancient Rome belonged to the so-called inconstant coercions (coercitio), they were respectively treated as “special circumstances courts” excluded from the regular Roman judicial system and performed criminal justice implementation, strictly in conditions of war. To repress the war torts, as well as to overcome the soldiers’ resistance, which at moments was violent, the king (rex) himself at first and the highest new established magistrates i.e. consuls (consules) afterwards, have been using various constrained acts. The authority of such enforcement against Roman soldiers sprang from their “military imperium” (imperium militiae). As most important criminal and judicial organs in conditions of war, responsible for maintenance of the military courtesy, were introduced the military commander (dux) and the array and their subsidiary organs were the cavalry commander, military legates, military tribunals, centurions and regents. In this paper, due to limited available space, we will only stick to the main military courts in ancient Rome. Keywords: military camp; tribunal; dux; recruiting; praetor. 1. Introduction “[The Romans...] strictly cared about punishments and awards of those who deserved praise or lecture… The military courtesy was grounded at the fear of laws, and god – for people, weapon, brad and money are the power of war! …It was nothing more than an army, that is well trained during muster; it was no possible for one to be defeated, who knows how to apply it!” [23]. -

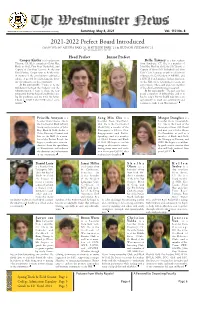

2021-2022 Prefect Board Introduced - - - Times

Westminster School Simsbury, CT 06070 www.westminster-school.org Saturday, May 8, 2021 Vol. 110 No. 8 2021-2022 Prefect Board Introduced COMPILED BY ALEYNA BAKI ‘21, MATTHEW PARK ‘21 & HUDSON STEDMAN ‘21 CO-EDITORS-IN-CHIEF, 2020-2021 Head Prefect Junior Prefect Cooper Kistler is a boarder from Bella Tawney is a day student Tiburon, CA. He is a member of John Hay, from Simsbury, CT. She is a member of Black & Gold, First Boys’ Basketball, and John Hay, Black & Gold, the SAC Board, a Captain of First Boys’ lacrosse. As the new Captain of First Girls’ Basketball and First Head Prefect, Cooper aims to be the voice Girls’ Cross Country, as well as a Horizons of everyone in the community to cultivate a volunteer, the Co-President of AWARE, and culture of growth by celebrating the diver- a HOTH board member. In her final year sity of perspectives in the community. on the Hill, she is determined to create an In his own words: “I want to be the environment, where each and every member middleman between the Students and the of the school community feels accepted. Administration. I want to share the new In her own words: “The past year has perspective that we have all established dur- posed a number of difficulties, and it is ing the pandemic, and use it for the better. hard to adapt, but we should take this as an I want to UNITE the NEW school com- opportunity to teach our community and munity." continue to make it our Westminster." Priscilla Ameyaw is a Sung Min Cho is a Margot Douglass is a boarder from Ghana. -

The Cultural Creation of Fulvia Flacca Bambula

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2017 The cultural creation of Fulvia Flacca Bambula. Erin Leigh Wotring University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Gender Commons, Intellectual History Commons, Political History Commons, Social History Commons, and the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation Wotring, Erin Leigh, "The cultural creation of Fulvia Flacca Bambula." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2691. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2691 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CULTURAL CREATION OF FULVIA FLACCA BAMBULA By Erin Leigh Wotring A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts in History Department of History University of Louisville Louisville, KY May, 2017 Copyright 2017 by Erin Leigh Wotring All rights reserved THE CULTURAL CREATION OF FULVIA FLACCA BAMBULA By Erin Leigh Wotring A Thesis Approved on April 14, 2017 by the following Thesis Committee: Dr. Jennifer Westerfeld, Director Dr. Blake Beattie Dr. Carmen Hardin ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. -

First Triumvirate and Rise of Octavian BY: Jake, Eliza and Maheen First Triumvirate

First Triumvirate and Rise of Octavian BY: Jake, Eliza and Maheen First Triumvirate • An alliance of the three most powerful men in Rome, Marcus Licinus Crassus, Gaius Julius Caesar, and Gneaus Pompey Magnus. Rome was in chaos and the 3 seized control of the Republic. • The three would dominate Roman politics for personal gains throughout the territories of the Republic. Julius Caesar • In Rome, Julius Caesar was elected as the tribune of the Plebs, military tribune, and governor of many provinces throughout the Republic. • Believed Crassus helped Julius Caesar win the election to become the Propraetor or governor of Hispania in 63 B.C.E. • Julius returned to Rome after his term as governor. Caesar had a business or political agreement with Pompey and Crassus in 60 B.C.E. Caesar was the consul while Pompey and Crassus were in the senate. • Created the First Triumvirate • After his term, Julius was in deeply in debt politically and financially to Crassus and desperately needed to raise money. Marcus Crassus • Crassus was the richest man in all the Roman Republic. He was sharp and clever in Roman politics. He would be a senator and even become consul a few times. • He was a mentor to Julius Caesar in his early career. • Gained much fame during the Spartacus rebellion but much of it was stolen by Pompey. • He was a longtime rival to Pompey Magnus and this would be his eventually downfall. He would ally with Caesar and Pompey, but strived for military victory over Pompey. He went to Parthia where he was defeated at Carrhae. -

Using Roman Law to Test the Validity of Livy's Caudine Forks Narrative

A Legal Interpretation of Livy's Caudine Sponsio: Using Roman Law to test the validity of Livy's Caudine Forks Narrative Michael Aston Although much has been written about Livy's account of the defeat of a Roman army at the hands of the Samnites at the Caudine Forks in 321 B.C., commentators do not agree as to whether the account describes an historical event. This paper offers a new approach to the problem, by analyzing the legal form and content of the sponsio (agreement) that acts as the backbone of Livy's narrative. The body of the paper analyzes Uvy's sponsio in detail, from a legal perspective. The analysis leads to the conclusion that U\y based his narrative upon the sponsio of Roman civil law. Since it is unlikely that the Romans and Samnites conducted their agreement on the basis of Roman private law, it is concluded that the events at the Caudine Forks are either fictional, or did not happen as LJvy describes them. Livy's account of the stunning Roman defeat at the Caudine Forks in 321 B.C. and the ensuing settlement is exciting and dramatic. But is it more than a well told story? Is it possible to prove or disprove Livy's account? The details of the Roman defeat recounted by Livy are well-known: a Samnite army under Gaius Pontius trapped a Roman army, under the command of consuls Spurius Postumius Albinus and Titus Veturius Calvinus, at the Caudine Forks.1 The Romans and Samnites subsequently reached an agreement (sponsio), whereby the Samnites proposed release of the captured army in exchange for a treaty of peace and Roman withdrawal from Samnite territory. -

The Late Republic in 5 Timelines (Teacher Guide and Notes)

1 180 BC: lex Villia Annalis – a law regulating the minimum ages at which a individual could how political office at each stage of the cursus honorum (career path). This was a step to regularising a political career and enforcing limits. 146 BC: The fall of Carthage in North Africa and Corinth in Greece effectively brought an end to Rome’s large overseas campaigns for control of the Mediterranean. This is the point that the historian Sallust sees as the beginning of the decline of the Republic, as Rome had no rivals to compete with and so turn inwards, corrupted by greed. 139 BC: lex Gabinia tabelleria– the first of several laws introduced by tribunes to ensure secret ballots for for voting within the assembliess (this one applied to elections of magistrates). 133 BC – the tribunate of Tiberius Gracchus, who along with his younger brother, is seen as either a social reformer or a demagogue. He introduced an agrarian land that aimed to distribute Roman public land to the poorer elements within Roman society (although this act quite likely increased tensions between the Italian allies and Rome, because it was land on which the Italians lived that was be redistributed). He was killed in 132 BC by a band of senators led by the pontifex maximus (chief priest), because they saw have as a political threat, who was allegedly aiming at kingship. 2 123-121 BC – the younger brother of Tiberius Gracchus, Gaius Gracchus was tribune in 123 and 122 BC, passing a number of laws, which apparent to have aimed to address a number of socio-economic issues and inequalities. -

Flavius Athanasius, Dux Et Augustalis Thebaidis – a Case Study on Landholding and Power in Late Antique Egypt

Imperium and Officium Working Papers (IOWP) Flavius Athanasius, dux et Augustalis Thebaidis – A case study on landholding and power in Late Antique Egypt Version 01 March 2013 Anna Maria Kaiser (University of Vienna, Department of Ancient History, Papyrology and Epigraphy) Abstract: From 565 to 567/568 CE Flavius Triadius Marianus Michaelius Gabrielius Constantinus Theodorus Martyrius Iulianus Athanasius was dux et Augustalis Thebaidis. Papyri mention him explicitly in this function, as the highest civil and military authority in the Thebaid, the southernmost province of the Eastern Roman Empire. Flavius Athanasius might be not the most typical dux et Augustalis Thebaidis concerning his career, but most typical concerning his powerful standing in society. And he has the benefit of being one of the better- known duces et Augustales Thebaidis in the second half of the 6th century. This article will focus first on his official competence as dux et Augustalis: The geographic area(s) of responsibility, the civil and military branches of power will be treated. Second will be his civil branch of power; documents show his own domus gloriosa and prove his involvement with the domus divina, the estates of members of the imperial family itself. We will end with a look at his integration in the network of power – both in the Egyptian provinces and beyond. © Anna Maria Kaiser 2013 [email protected] Anna Kaiser 1 Flavius Athanasius, dux et Augustalis Thebaidis – A case study on landholding and power in Late Antique Egypt* Anna Maria Kaiser From 565 to 567/568 CE Flavius Triadius Marianus Michaelius Gabrielius Constantinus Theodorus Martyrius Iulianus Athanasius was dux et Augustalis Thebaidis. -

The Military Reforms of Gaius Marius in Their Social, Economic, and Political Context by Michael C. Gambino August, 2015 Directo

The Military Reforms of Gaius Marius in their Social, Economic, and Political Context By Michael C. Gambino August, 2015 Director of Thesis: Dr. Frank Romer Major Department: History Abstract The goal of this thesis is, as the title affirms, to understand the military reforms of Gaius Marius in their broader societal context. In this thesis, after a brief introduction (Chap. I), Chap. II analyzes the Roman manipular army, its formation, policies, and armament. Chapter III examines Roman society, politics, and economics during the second century B.C.E., with emphasis on the concentration of power and wealth, the legislative programs of Ti. And C. Gracchus, and the Italian allies’ growing demand for citizenship. Chap. IV discusses Roman military expansion from the Second Punic War down to 100 B.C.E., focusing on Roman military and foreign policy blunders, missteps, and mistakes in Celtiberian Spain, along with Rome’s servile wars and the problem of the Cimbri and Teutones. Chap. V then contextualizes the life of Gaius Marius and his sense of military strategy, while Chap VI assesses Marius’s military reforms in his lifetime and their immediate aftermath in the time of Sulla. There are four appendices on the ancient literary sources (App. I), Marian consequences in the Late Republic (App. II), the significance of the legionary eagle standard as shown during the early principate (App. III), and a listing of the consular Caecilii Metelli in the second and early first centuries B.C.E. (App. IV). The Marian military reforms changed the army from a semi-professional citizen militia into a more professionalized army made up of extensively trained recruits who served for longer consecutive terms and were personally bound to their commanders. -

Leges Regiae

DIPARTIMENTO IURA SEZIONE STORIA DEL DIRITTO UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI PALERMO ANNALI DEL SEMINARIO GIURIDICO (Aupa) Fontes - 3.1 Revisione ed integrazione dei Fontes Iuris Romani Anteiustiniani (FIRA) Studi preparatori I Leges a cura di Gianfranco Purpura G. Giappichelli Editore - Torino DIPARTIMENTO IURA SEZIONE STORIA DEL DIRITTO UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI PALERMO ANNALI DEL SEMINARIO GIURIDICO (AuPA) Fontes - 3.1 Revisione ed integrazione dei Fontes Iuris Romani Anteiustiniani (FIRA) Studi preparatori I Leges a cura di Gianfranco Purpura G. Giappichelli Editore - Torino © Copyright 2012 - G. GIAPPICHELLI EDITORE - TORINO VIA PO, 21 - TEL. 011-81.53.111 - FAX 011-81.25.100 http://www.giappichelli.it ISBN/EAN 978-88-348-3821-1 Il presente volume viene pubblicato con il contributo dei fondi PRIN 2008, nell’ambito della ricerca dal titolo “Revisione ed integrazione dei Fontes Iuris Romani Antejustiniani – FIRA”, coordinata dal Prof. Gianfranco Purpura. Stampa: OfficineT ipografiche Aiello & Provenzano s.r.l. Sede legale ed amministrativa: Via del Cavaliere, 93 - Tel. +39.091.903327 +39.091.902385 Fax +39.091.909419 - Stabilimento: Via del Cavaliere, 87/g - Tel. +39.091.901873 90011 Bagheria (PA) Le fotocopie per uso personale del lettore possono essere effettuate nei limiti del 15% di ciascun volume/fascicolo di periodico dietro pagamento alla SIAE del compenso previsto dall’art. 68, commi 4 e 5, della legge 22 aprile 1941, n. 633. Le fotocopie effettuate per finalità di carattere professionale, economico o commerciale o comunque per uso diverso da quello personale possono essere effettuate a seguito di specifica autorizzazione rilasciata da CLEARedi, Centro Licenze e Autorizzazioni per le Riproduzioni Editoriali, Corso di Porta Romana 108, 20122 Milano, e-mail [email protected] e sito web www.clearedi.org INDICE Prefazione (G. -

De Ornanda Instruendaque Urbe Anne Truetzel

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) 1-1-2011 De Ornanda Instruendaque Urbe Anne Truetzel Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Recommended Citation Truetzel, Anne, "De Ornanda Instruendaque Urbe" (2011). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 527. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/527 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY Department of Classics De Ornanda Instruendaque Urbe: Julius Caesar’s Influence on the Topography of the Comitium-Rostra-Curia Complex by Anne E. Truetzel A thesis presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts August 2011 Saint Louis, Missouri ~ Acknowledgments~ I would like to take this opportunity to thank the Classics department at Washington University in St. Louis. The two years that I have spent in this program have been both challenging and rewarding. I thank both the faculty and my fellow graduate students for allowing me to be a part of this community. I now graduate feeling well- prepared for the further graduate study ahead of me. There are many people without whom this project in particular could not have been completed. First and foremost, I thank Professor Susan Rotroff for her guidance and support throughout this process; her insightful comments and suggestions, brilliant ideas and unfailing patience have been invaluable.