January 4, 1987 - Conrail’S Darkest Day

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reporting Marks

Lettres d'appellation / Reporting Marks AA Ann Arbor Railroad AALX Advanced Aromatics LP AAMX ACFA Arrendadora de Carros de Ferrocarril S.A. AAPV American Association of Private RR Car Owners Inc. AAR Association of American Railroads AATX Ampacet Corporation AB Akron and Barberton Cluster Railway Company ABB Akron and Barberton Belt Railroad Company ABBX Abbott Labs ABIX Anheuser-Busch Incorporated ABL Alameda Belt Line ABOX TTX Company ABRX AB Rail Investments Incorporated ABWX Asea Brown Boveri Incorporated AC Algoma Central Railway Incorporated ACAX Honeywell International Incorporated ACBL American Commercial Barge Lines ACCX Consolidation Coal Company ACDX Honeywell International Incorporated ACEX Ace Cogeneration Company ACFX General Electric Rail Services Corporation ACGX Suburban Propane LP ACHX American Cyanamid Company ACIS Algoma Central Railway Incorporated ACIX Great Lakes Chemical Corporation ACJR Ashtabula Carson Jefferson Railroad Company ACJU American Coastal Lines Joint Venture Incorporated ACL CSX Transportation Incorporated ACLU Atlantic Container Line Limited ACLX American Car Line Company ACMX Voith Hydro Incorporated ACNU AKZO Chemie B V ACOU Associated Octel Company Limited ACPX Amoco Oil Company ACPZ American Concrete Products Company ACRX American Chrome and Chemicals Incorporated ACSU Atlantic Cargo Services AB ACSX Honeywell International Incorporated ACSZ American Carrier Equipment ACTU Associated Container Transport (Australia) Limited ACTX Honeywell International Incorporated ACUU Acugreen Limited ACWR -

Semiannual Report to Congress Go Green!

Go Green! Consumes less energy than car or air travel* Semiannual Report to Congress Report #41 H 10/01/09 – 3/31/10 ON THE COVER Amtrak® Empire Builder® Message from the Inspector General am pleased to present the first Semiannual Report We made a series of recommendations to improve to Congress since my appointment as Amtrak the effectiveness and efficiency of training and IInspector General in November 2009. In addition employee development, focusing on developing and to reporting on the Office of Inspector General’s (OIG) implementing a corporate-wide training and employee accomplishments during the six-month period ending development strategy. This would ensure that training March 31, 2010, I am identifying several significant aligns with the overall corporate strategy and provides challenges the OIG faces and the ongoing and planned employees with the skills needed to assume leadership actions we are pursuing to overcome the challenges. roles in the future. Significant Accomplishments Management recently agreed with all of our recommendations and provided a plan to implement During this semi-annual reporting period, the OIG them. It is important, however, for management to continued to identify opportunities to reduce costs, stay focused on making near-term improvements, improve management operations, enhance revenue, and because effective training and development practices institute more efficient and effective business processes. will be a key component of Amtrak’s ability to deliver For example: high quality services. H An OIG audit of the monthly on time performance H The Office of Investigations was instrumental in (OTP) bills and schedules from April 1993 through securing convictions and restitutions in multiple theft April 2004 disclosed that CSX inaccurately billed schemes. -

Rio Grande Station Cape May County, NJ Name of Property County and State 5

NPS Form 10-900 JOYf* 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) !EO 7 RECE!\ United States Department of the Interior National Park Service n m National Register of Historic Places Registration Form ii:-:r " HONAL PARK" -TIO.N OFFICE This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategones from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form I0-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property________________________________________________ historic name R'Q Grande Station____________________________________ other names/site number Historic Cold Spring Village Station______________________ 2. Location street & number 720 Route 9 D not for publication city or town Lower Township D vicinity state New Jersey_______ code NJ county Cape May_______ code 009 zip code J5§204 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this Q nomination G request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property S meets D doss not meet the National Register criteria. -

Multi-Municipal Comprehensive Plan

GWA Planning Area Acknowledgements 2017 COMPREHENSIVE PLAN REVIEW AND IMPLEMENTATION STRATEGY Plan Adoptions WILLIAMSPORT CITY COUNCIL – Adopted October 26, 2017 DUBOISTOWN BOROUGH COUNCIL – Adopted December 7, 2017 SOUTH WILLIAMSPORT BOROUGH COUNCIL – Adopted November 13, 2017 ARMSTRONG TOWNSHIP BOARD OF SUPERVISORS – Adopted August 10, 2017 LOYALSOCK TOWNSHIP BOARD OF SUPERVISORS – Adopted August 22, 2017 OLD LYCOMING TOWNSHIP BOARD OF SUPERVISORS – Adopted September 12, 2017 *Please refer to Appendix F for the Adopted Municipal Resolutions Lycoming 2030: Plan the Possible 1 GWA Planning Area Acknowledgements 2017 COMPREHENSIVE PLAN REVIEW AND IMPLEMENTATION STRATEGY Acknowledgements Greater Williamsport Alliance (GWA) Planning Advisory Team (PAT) MUNICIPALITIES JAMES CRAWFORD, LYCOMING COUNTY PLANNING COMMISSION GABRIEL CAMPANA, CITY OF WILLIAMSPORT BONNIE KATZ, CITY OF WILLIAMSPORT JOHN GRADO, CITY OF WILLIAMSPORT JOE GIRARDI, CITY OF WILLIAMSPORT GARY KNARR, CITY OF WILLIAMSPORT MICHAEL CASCHERA, DUBOISTOWN BOROUGH ROBIN RUNDIO, DUBOISTOWN BOROUGH MICHAEL MILLER, SOUTH WILLIAMSPORT BOROUGH JIM DUNN, ARMSTRONG TOWNSHIP/LYCOMING COUNTY PLANNING COMMISSION DICK STAIB, ARMSTRONG TOWNSHIP MARC SORTMAN, LOYALSOCK TOWNSHIP VIRGINIA EATON, LOYALSOCK TOWNSHIP JOHN BOWER, LOYALSOCK TOWNSHIP BILL BURDETT, LOYALSOCK TOWNSHIP LINDA MAZZULLO, OLD LYCOMING TOWNSHIP JOHN ECK, OLD LYCOMING TOWNSHIP BOB WHITFORD, OLD LYCOMING TOWNSHIP MUNICIPAL AUTHORITIES/ENTITIES DOUG KEITH, WILLIAMSPORT MUNICIPAL WATER AUTHORITY/WILLIAMSPORT SANITARY AUTHORITY -

Personal Rapid Transit (PRT) New Jersey

Personal Rapid Transit (PRT) for New Jersey By ORF 467 Transportation Systems Analysis, Fall 2004/05 Princeton University Prof. Alain L. Kornhauser Nkonye Okoh Mathe Y. Mosny Shawn Woodruff Rachel M. Blair Jeffery R Jones James H. Cong Jessica Blankshain Mike Daylamani Diana M. Zakem Darius A Craton Michael R Eber Matthew M Lauria Bradford Lyman M Martin-Easton Robert M Bauer Neset I Pirkul Megan L. Bernard Eugene Gokhvat Nike Lawrence Charles Wiggins Table of Contents: Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction to Personal Rapid Transit .......................................................................................... 3 New Jersey Coastline Summary .................................................................................................... 5 Burlington County (M. Mosney '06) ..............................................................................................6 Monmouth County (M. Bernard '06 & N. Pirkul '05) .....................................................................9 Hunterdon County (S. Woodruff GS .......................................................................................... 24 Mercer County (M. Martin-Easton '05) ........................................................................................31 Union County (B. Chu '05) ...........................................................................................................37 Cape May County (M. Eber '06) …...............................................................................................42 -

November 14, 2014 in Honor of Veterans Day This Week, My Thanks

Dear All: November 14, 2014 In honor of Veterans Day this week, my thanks go out to the men and women of yesterday, today and tomorrow who have and who will sacrifice so much for the U.S.A. It seems to me, the train world really comes alive during the holidays to help us remember years gone by. So many of you volunteer your time to set up and run a layout at various locations, how amazing it is because you are touching the lives of so many in a positive and healthy way. Bravo! I would love to include YOUR story with the next e‐ blast that connects your family memories with the holiday season and the world of trains. I think it would be great to share these stories over the next several weeks leading up to the end of 2014! What did you say? You have pictures to go along with the story, well send them along to me and as long as they are family friendly I’ll share them with those that read the eblast. As a reminder, the eblasts and attachments will be placed on the WB&A website under the “About” tab for your viewing/sharing pleasure http://www.wbachapter.org/2014%20E‐ Blast%20Page.htm The attachments are contained in the one PDF attached to this email in an effort to streamline the sending of this email and to ensure the attachments are able to be received. If you need a PDF viewer to read the document which can be downloaded free at http://www.adobe.com/products/acrviewer/acrvd nld.html. -

Chapter Four

CHAPTER FOUR EXISTING TRANSPORTATION SYSTEM INVENTORY WITH NEEDS ASSESSMENT ANALYSIS This Chapter of the WATS Long Range Transportation Plan provides a description of the existing multi-modal transportation system in Lycoming County encompassing highways and bridges, public transportation, airports, railroads and bike / pedestrian facilities. There are no waterway or inland ports located in the County. An inventory of current transportation assets by transportation mode will be provided, including a current physical condition and operational performance needs assessment. This data driven inventory and assessment is important to properly address transportation asset management needs and to improve operational performance of the overall system in terms of public safety, security, efficiency and cost effective movement of people and goods. HIGHWAY SYSTEM Highway Designations / Classification System According to the PennDOT Bureau of Planning and Research, there are 1,995.18 linear miles of publicly owned roadways throughout Lycoming County. PennDOT owns 716.59 linear miles, (35%) of public roadways in Lycoming County. In addition, there are 1,258.86 miles, (63%) of locally-owned roadways owned by 52 different local municipalities included on the PennDOT Liquid Fuels System. Other agencies own the remainder of roads in the County. Lycoming County government only owns two roads which are County Farm Road at the Lysock View county complex housing the Department of Public Safety (911 center), Pre- Release and county farm and an entrance road to the White Deer Recreation Complex. There are federal designations and classifications established for highway systems in the nation as noted in the following sections. Road Functional Classification System The Federal Highway Administration, PennDOT and Metropolitan & Rural Planning Organizations cooperatively establish and update maps that delineate various road classifications which group roadways into a hierarchy based on the type of highway service provided. -

Transportation Trips, Excursions, Special Journeys, Outings, Tours, and Milestones In, To, from Or Through New Jersey

TRANSPORTATION TRIPS, EXCURSIONS, SPECIAL JOURNEYS, OUTINGS, TOURS, AND MILESTONES IN, TO, FROM OR THROUGH NEW JERSEY Bill McKelvey, Editor, Updated to Mon., Mar. 8, 2021 INTRODUCTION This is a reference work which we hope will be useful to historians and researchers. For those researchers wanting to do a deeper dive into the history of a particular event or series of events, copious resources are given for most of the fantrips, excursions, special moves, etc. in this compilation. You may find it much easier to search for the RR, event, city, etc. you are interested in than to read the entire document. We also think it will provide interesting, educational, and sometimes entertaining reading. Perhaps it will give ideas to future fantrip or excursion leaders for trips which may still be possible. In any such work like this there is always the question of what to include or exclude or where to draw the line. Our first thought was to limit this work to railfan excursions, but that soon got broadened to include rail specials for the general public and officials, special moves, trolley trips, bus outings, waterway and canal journeys, etc. The focus has been on such trips which operated within NJ; from NJ; into NJ from other states; or, passed through NJ. We have excluded regularly scheduled tourist type rides, automobile journeys, air trips, amusement park rides, etc. NOTE: Since many of the following items were taken from promotional literature we can not guarantee that each and every trip was actually operated. Early on the railways explored and promoted special journeys for the public as a way to improve their bottom line. -

The Story of Federal Express and Its Founder Fred Smith

A Review of OVERNIGHT SUCCESS: FEDERAL EXPRESS AND ITS RENEGADE CREATOR by Vance Trimble reviewed by Bernhard Reichert INTRODUCTION This article is divided in two parts. The first part discusses common traits of new business ventures. The second, and major part, is the story of Federal Express and its founder Fred Smith. The primary source of the discussion of Federal Express is Vance Trimble’s Overnight Success.1 A REVIEW OF SUCCESSFUL BUSINESS VENTURES There seems to be a pattern exhibited by successful new companies which they seem to have in common: Communication: The management style in new companies is very informal. Communication and work organization is easy going. Work responsibilities are not clearly defined and change; job rotation is practiced; and responsibilities are overlapping. Open access to the person in charge seems to improve work motivation and lead to an esprit de corps. Thinking about this makes perfect sense. Complaining to your boss in a casual company is like a nice talk in a pub. It gives you the feeling your criticism, and you, are taken seriously, and by being able to go to the person in charge you feel it is the first step in turning around a bad situation. Once companies become larger and open access to the person in charge is no longer possible, workers can no longer direct 33 JOURNAL OF BUSINESS LEADERSHIP - 2000-2001 their complaints to top management. Immediate superiors, who should be the person to talk to about suggestions and criticism, are busy meeting their performance targets. They do not appreciate people complaining and view complainants as potential sources of trouble. -

FRA Guide for Preparing Accident/Incident Reports

FRA Guide for Preparing Accident/Incident Reports U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Railroad Administration Office of Railroad Safety DOT/FRA/RRS-22 Published: May 23, 2011 Effective: July 1, 2011 This page intentionally left blank MAIL MONTHLY ACCIDENT/INCIDENT REPORTING SUBMISSIONS TO: FRA Project Office 2600 Park Tower Drive, Suite 1000 Vienna, VA 22180 Please refer to http://safetydata.fra.dot.gov/OfficeofSafety, and click on “Click Here for Changes in Accident/Incident Recordkeeping and Reporting” for updated information. Preface The Federal Railroad Administration’s (FRA) regulations on reporting railroad accidents/incidents are found primarily in Title 49 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Part 225.1 The purpose of the regulations in Part 225 is to provide FRA with accurate information concerning the hazards and risks that exist on the Nation’s railroads. See § 225.1. FRA needs this information to effectively carry out its regulatory and enforcement responsibilities under the Federal railroad safety statutes.2 FRA also uses this information for determining comparative trends of railroad safety and to develop hazard elimination and risk reduction programs that focus on preventing railroad injuries and accidents. 1 For brevity, further references in the Guide to sections in 49 CFR Part 225 will omit “49 CFR” and include only the section, e.g., § 225.9. 2 Title 49 U.S.C. chapters 51, 201–213. iv Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 1 1. Overview of Railroad Accident/Incident Recordkeeping and Reporting Requirements and Miscellaneous Provisions and Information ............................................................................... 4 1.1 General ............................................................................................................................. 4 1.1.1 Purpose of the FRA Guide for Preparing Accident/Incident Reports ....................... -

Federal Register / Vol. 61, No. 170 / Friday, August 30, 1996 / Notices

46020 Federal Register / Vol. 61, No. 170 / Friday, August 30, 1996 / Notices 1201 Constitution Avenue, N.W., series of anticipated transactions that miles of rail line owned by Consolidated Washington, DC 20423 and served on: would connect Lycoming with any other Rail Corporation known as the Eric M. Hocky, Gollatz, Griffin & Ewing, railroad in its corporate family; and (3) Lewistown Cluster in Mifflin County, P.C., 213 West Miner Street, P. O. Box the transaction does not involve a Class PA. Juniata will become a Class III rail 796, West Chester, PA 19381±0796. I railroad. The transaction therefore is carrier.3 Consummation was expected to Decided: August 22, 1996. exempt from the prior approval occur on or after August 15, 1996. By the Board, Joseph H. Dettmar, Acting requirements of 49 U.S.C. 11323. See 49 If the notice contains false or Director, Office of Proceedings. CFR 1180.2(d)(2). misleading information, the exemption Vernon A. Williams, Under 49 U.S.C. 10502(g), the Board is void ab initio. Petitions to revoke the may not use its exemption authority to Secretary. exemption under 49 U.S.C. 10502(d) relieve a rail carrier of its statutory [FR Doc. 96±22206 Filed 8±29±96; 8:45 am] may be filed at any time. The filing of obligation to protect the interests of its a petition to revoke will not BILLING CODE 4915±00±P employees. Section 11326(c), however, automatically stay the transaction. does not provide for labor protection for An original and 10 copies of all Surface Transportation Board 1 transactions under sections 11324 and pleadings, referring to STB Finance 11325 that involve only Class III Docket No. -

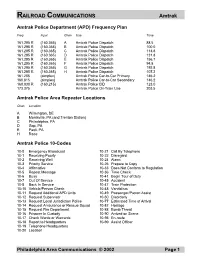

RAILROAD COMMUNICATIONS Amtrak

RAILROAD COMMUNICATIONS Amtrak Amtrak Police Department (APD) Frequency Plan Freq Input Chan Use Tone 161.295 R (160.365) A Amtrak Police Dispatch 88.5 161.295 R (160.365) B Amtrak Police Dispatch 100.0 161.295 R (160.365) C Amtrak Police Dispatch 114.8 161.295 R (160.365) D Amtrak Police Dispatch 131.8 161.295 R (160.365) E Amtrak Police Dispatch 156.7 161.295 R (160.365) F Amtrak Police Dispatch 94.8 161.295 R (160.365) G Amtrak Police Dispatch 192.8 161.295 R (160.365) H Amtrak Police Dispatch 107.2 161.205 (simplex) Amtrak Police Car-to-Car Primary 146.2 160.815 (simplex) Amtrak Police Car-to-Car Secondary 146.2 160.830 R (160.215) Amtrak Police CID 123.0 173.375 Amtrak Police On-Train Use 203.5 Amtrak Police Area Repeater Locations Chan Location A Wilmington, DE B Morrisville, PA (and Trenton Station) C Philadelphia, PA D Gap, PA E Paoli, PA H Race Amtrak Police 10-Codes 10-0 Emergency Broadcast 10-21 Call By Telephone 10-1 Receiving Poorly 10-22 Disregard 10-2 Receiving Well 10-24 Alarm 10-3 Priority Service 10-26 Prepare to Copy 10-4 Affirmative 10-33 Does Not Conform to Regulation 10-5 Repeat Message 10-36 Time Check 10-6 Busy 10-41 Begin Tour of Duty 10-7 Out Of Service 10-45 Accident 10-8 Back In Service 10-47 Train Protection 10-10 Vehicle/Person Check 10-48 Vandalism 10-11 Request Additional APD Units 10-49 Passenger/Patron Assist 10-12 Request Supervisor 10-50 Disorderly 10-13 Request Local Jurisdiction Police 10-77 Estimated Time of Arrival 10-14 Request Ambulance or Rescue Squad 10-82 Hostage 10-15 Request Fire Department