No Will, No Way: US-Funded Security Sector Reform in the Democratic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report of the Interim Chairperson of the Commission of the African Union on the Situation in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Drc)

AFRICAN UNION UNION AFRICAINE UNIÃO AFRICANA P. O. Box 3243, Addis Ababa, ETHIOPIA Tel.: (251-1) 513822 Fax: (251-1) 519321 Email: [email protected] EIGHTY SIXTH ORDINARY SESSION OF THE CENTRAL ORGAN OF THE MECHANISM FOR CONFLICT PREVENTION, MANAGEMENT AND RESOLUTION 29 October 2002 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Central Organ/MEC/AMB/2 (LXXXVI) REPORT OF THE INTERIM CHAIRPERSON OF THE COMMISSION OF THE AFRICAN UNION ON THE SITUATION IN THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO (DRC) Central Organ/MEC/AMB/2 (LXXXVI) Page 1 REPORT OF THE INTERIM CHAIRPERSON OF THE COMMISSION OF THE AFRICAN UNION ON THE SITUATION IN THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO (DRC) I. INTRODUCTION 1. At the 76th Ordinary Session of the OAU Council of Ministers held in Durban, South Africa, from 4 to 6 July 2002, I reported on the development of the Peace Process in the DRC and on the efforts made by the OAU, the UN and the International Community to implement the Lusaka Ceasefire Agreement. In Decision CM/Dec. 663 (LXXVI) Council had, among others, urged the Parties to the Peace Process to fulfill their obligations issuing from the Lusaka Agreement, expressed its concern about the delay in the process of the withdrawal of foreign troops, encouraged the signatories to the Lusaka Agreement to continue their contacts in order to establish the conditions conducive to its implementation, requested the United Nations to strengthen the capacity and expand the mandate of MONUC to enable it carry out successfully the tasks assigned to it in Phase III of its deployment and appealed to the International Community to continue to support the Peace Process in the DRC. -

Executive Summary

Monthly Protection Monitoring Report – North Kivu September 2015 Executive Summary 2845 incidents have been recorded in September 2015. The number has decreased by 6,3% compared to August 2015 pendant, when 3037 incidents were reported. The territory Incidents per territory of Rutshuru has had the BENI 369 highest LUBERO 369 number of MASISI 639 incidents in NYIRAGONGO 133 September RUTSHURU 919 2015 WALIKALE 416 TOTAL 2845 Incidents per Incidents per alleged perpetrator category of victim Nombre des cas par type d’incident The majority of incidents in September 2015 were violations to the right of property and liberty PROTECTION MONITORING PMS Province du Nord Kivu 2 | UNHCR Protection Monitoring Nor th K i v u – Sept. Monthly Report PROTECTION MONITORING PMS Province du Nord Kivu I. Summary of main protection concerns Throughout September 2015, the PMS has registered 59,8% less internal displacement than in August 2015. This decrease can be justified by the relative calm perceived in significant displacement areas. On 17 September 2015, alleged NDC Cheka members pillaged Kalehe village to the Northeast of Bunyatenge and kidnapped around 30 people that were forced to transport the stolen goods to Mwanza and Mutiri, in Lubero territory. II. Protection context by territory MASISI The security situation in Masisi was characterised by clashes between FARDC and FDLR, between two different factions of FDDH (FDDH/Tuombe and FDDH/Mugwete) and between FARDC and APCLS. These conflicts have led to the massive displacement of the population from the areas affected by fighting followed by looting, killings and other violations. In Bibwe, around 400 families were displaced, among which 72 households are staying in a church and a school in Bibwe and around 330 families created a new site, accessible by car, around 2km from the Bibwe site. -

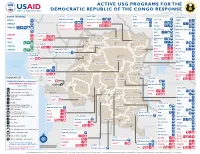

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS for the DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC of the CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS FOR THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20 BAS-UELE HAUT-UELE ITURI S O U T H S U D A N COUNTRYWIDE NORTH KIVU OCHA IMA World Health Samaritan’s Purse AIRD Internews CARE C.A.R. Samaritan’s Purse Samaritan’s Purse IMA World Health IOM UNHAS CAMEROON DCA ACTED WFP INSO Medair FHI 360 UNICEF Samaritan’s Purse Mercy Corps IMA World Health NRC NORD-UBANGI IMC UNICEF Gbadolite Oxfam ACTED INSO NORD-UBANGI Samaritan’s WFP WFP Gemena BAS-UELE Internews HAUT-UELE Purse ICRC Buta SCF IOM SUD-UBANGI SUD-UBANGI UNHAS MONGALA Isiro Tearfund IRC WFP Lisala ACF Medair UNHCR MONGALA ITURI U Bunia Mercy Corps Mercy Corps IMA World Health G A EQUATEUR Samaritan’s NRC EQUATEUR Kisangani N Purse WFP D WFPaa Oxfam Boende A REPUBLIC OF Mbandaka TSHOPO Samaritan’s ATLANTIC NORTH GABON THE CONGO TSHUAPA Purse TSHOPO KIVU Lake OCEAN Tearfund IMA World Health Goma Victoria Inongo WHH Samaritan’s Purse RWANDA Mercy Corps BURUNDI Samaritan’s Purse MAI-NDOMBE Kindu Bukavu Samaritan’s Purse PROGRAM KEY KINSHASA SOUTH MANIEMA SANKURU MANIEMA KIVU WFP USAID/BHA Non-Food Assistance* WFP ACTED USAID/BHA Food Assistance** SA ! A IMA World Health TA N Z A N I A Kinshasa SH State/PRM KIN KASAÏ Lusambo KWILU Oxfam Kenge TANGANYIKA Agriculture and Food Security KONGO CENTRAL Kananga ACTED CRS Cash Transfers For Food Matadi LOMAMI Kalemie KASAÏ- Kabinda WFP Concern Economic Recovery and Market Tshikapa ORIENTAL Systems KWANGO Mbuji T IMA World Health KWANGO Mayi TANGANYIKA a KASAÏ- n Food Vouchers g WFP a n IMC CENTRAL y i k -

UNJHRO) MONUSCO – OHCHR March 2021 REPORTED HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS in DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC of the CONGO (DRC)

Protection of civilians: Human rights violations documented in provinces affected by conflict United Nations Joint Human Rights Office in the DRC (UNJHRO) MONUSCO – OHCHR March 2021 REPORTED HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS IN DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO (DRC) Figure 1. Percentage of violations per territory Figure 2. Number of violations per province in DRC SOUTH CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC SUDAN North Kivu Tanganyika Bas-Uele Haut-Uele Masisi 79% 21 Kalemie 36% 65 North-Ubangi Beni 64 36 Manono0 100 2 UGANDA CAMEROON South-Ubangi Rutshuru 69 31 Moba0 100 Ituri Mongala Lubero 29 71 77 Nyiragongo 86 14 Maniema Tshopo Walikale 90 10 Kabambare 63% 395 CONGO Equateur North Butembo0 100 Kasongo0 100 Kivu Kibombo0 100 GABON Tshuapa 359 South Kivu RWANDA Kasai Shabunda 82% 18 Mai-Ndombe Kamonia (Kas.)0 100% Kinshasa Uvira 33 67 5 BURUNDI Llebo (Kas.)0 100 Sankuru 15 63 Fizi 33 67 Kasai South Tshikapa (Kas.)0 100 Maniema Kivu Kabare 100 0 Luebo (Kas.)0 100 Kwilu 23 TANZANIA Walungu 29 71 Kananga (Kas. C)0 100 Lomami Bukavu0 100 22 4 Demba (Kas. C)0 100 Kongo 46 Mwenga 67 33 Central Luiza (Kas. C)0 100 Kwango Tanganyika Kalehe0 100 Kasai Dimbelenge (Kas. C)0 100 Central Haut-Lomami Ituri Miabi (Kas. O)0 100 Kasai 0 100 ANGOLA Oriental Irumu 88% 12 Mbuji-Mayi (Kas. O) Haut- Djugu 64 36 Lualaba Bas-Uele Katanga Mambasa 30 70 Buta0 100% Mahagi 100 0 % by armed groups % by State agents The boundaries and names shown and designations ZAMBIA used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

UN Security Council, Children and Armed Conflict in the DRC, Report of the Secretary General, October

United Nations S/2020/1030 Security Council Distr.: General 19 October 2020 Original: English Children and armed conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Report of the Secretary-General Summary The present report, submitted pursuant to Security Council resolution 1612 (2005) and subsequent resolutions, is the seventh report of the Secretary-General on children and armed conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It covers the period from 1 January 2018 to 31 March 2020 and the information provided focuses on the six grave violations committed against children, the perpetrators thereof and the context in which the violations took place. The report sets out the trends and patterns of grave violations against children by all parties to the conflict and provides details on progress made in addressing grave violations against children, including through action plan implementation. The report concludes with a series of recommendations to end and prevent grave violations against children in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and improve the protection of children. 20-13818 (E) 171120 *2013818* S/2020/1030 I. Introduction 1. The present report, submitted pursuant to Security Council resolution 1612 (2005) and subsequent resolutions, is the seventh report of the Secretary-General on children and armed conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and covers the period from 1 January 2018 to 31 March 2020. It contains information on the trends and patterns of grave violations against children since the previous report (S/2018/502) and an outline of the progress and challenges since the adoption by the Working Group on Children and Armed Conflict of its conclusions on children and armed conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, in July 2018 (S/AC.51/2018/2). -

A Colonial Genealogy of Violence Against Tutsi Women in The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Gender-Based Violence and Submerged Histories: A Colonial Genealogy of Violence Against Tutsi Women in the 1994 Rwandan Genocide A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Gender Studies by Helina Asmelash Beyene 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Gender-Based Violence and Submerged Histories: A Colonial Genealogy of Violence Against Tutsi Women in the 1994 Rwandan Genocide by Helina Asmelash Beyene Doctor of Philosophy in Gender Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Sondra Hale, Chair My dissertation is a genealogical study of gender-based violence (GBV) during the 1994 Rwandan genocide. A growing body of feminist scholarship argues that GBV in conflict zones results mainly from a continuum of patriarchal violence that is condoned outside the context of war in everyday life. This literature, however, fails to account for colonial and racial histories that also inform the politics of GBV in African conflicts. My project examines the question of the colonial genealogy of GBV by grounding my inquiry within postcolonial, transnational and intersectional feminist frameworks that center race, historicize violence, and decolonize knowledge production. I employ interdisciplinary methods that include (1) discourse analysis of the gender-based violence of Belgian rule and Tutsi women’s iconography in colonial texts; (2) ii textual analysis of the constructions of Tutsi women’s sexuality and fertility in key official documents on overpopulation and Tutsi refugees in colonial and post-independence Rwanda; and (3) an ethnographic study that included leading anti gendered violence activists based in Kigali, Rwanda, to assess how African feminists account for the colonial legacy of gendered violence in the 1994 genocide. -

World Bank Document

AID AND REFORM THE CASE OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO Public Disclosure Authorized TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Abstract 2 Introduction 3 Part One: Economic Policy and Performance 3 The chaotic years following independence 3 The early Mobutu years 4 Public Disclosure Authorized The shocks of 1973-75 4 The recession years and early attempts at reform 5 The 1983 reform 5 Renewed fiscal laxity 5 The promise of structural reforms 6 The last attempt 7 Part Two: Aid and Reform 9 Financial flows and reform 9 Adequacy of the reform agenda 10 Public resource management 12 Public Disclosure Authorized The political dimension of reform 13 Conclusion 14 This paper is a contribution to the research project initiated by the Development Research Group of the World Bank on Aid and Reform in Africa. The objective of the study is to arrive at a better understanding of the causes of policy reforms and the foreign aid-reform link. The study is to focus on the real causes of reform and if and how aid in practice has encouraged, generated, influenced, supported or retarded reforms. A series of country case studies were launched to achieve the objective of the research project. The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) was selected among nine other countries in Africa. The case study has been conducted by a team of two researchers, including Public Disclosure Authorized Gilbert Kiakwama, who was Congo’s Minister of Finance in 1983-85, and Jerome Chevallier. AID AND REFORM The case of the Democratic Republic of Congo ABSTRACT. i) During its first years of independence, the Democratic Republic of the Congo plunged into anarchy and became a hot spot in the cold war between the Soviet Union and the West. -

Democratic Republic of Congo

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO 350 Fifth Ave 34 th Floor New York, N.Y. 10118-3299 http://www.hrw.org (212) 290-4700 Vol. 15, No. 11 (A) - July 2003 I hid in the mountains and went back down to Songolo at about 3:00 p.m. I saw many people killed and even saw traces of blood where people had been dragged. I counted 82 bodies most of whom had been killed by bullets. We did a survey and found that 787 people were missing – we presumed they were all dead though we don’t know. Some of the bodies were in the road, others in the forest. Three people were even killed by mines. Those who attacked knew the town and posted themselves on the footpaths to kill people as they were fleeing. -- Testimony to Human Rights Watch ITURI: “COVERED IN BLOOD” Ethnically Targeted Violence In Northeastern DR Congo 1630 Connecticut Ave, N.W., Suite 500 2nd Floor, 2-12 Pentonville Road 15 Rue Van Campenhout Washington, DC 20009 London N1 9HF, UK 1000 Brussels, Belgium TEL (202) 612-4321 TEL: (44 20) 7713 1995 TEL (32 2) 732-2009 FAX (202) 612-4333 FAX: (44 20) 7713 1800 FAX (32 2) 732-0471 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] “You cannot escape from the horror” This story of fifteen-year-old Elise is one of many in Ituri. She fled one attack after another and witnessed appalling atrocities. Walking for more than 300 miles in her search for safety, Elise survived to tell her tale; many others have not. -

Democratic Republic of Congo Democratic Republic of Congo Gis Unit, Monuc Africa

Map No.SP. 103 ADMINISTRATIVE MAP OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO GIS UNIT, MONUC AFRICA 12°30'0"E 15°0'0"E 17°30'0"E 20°0'0"E 22°30'0"E 25°0'0"E 27°30'0"E 30°0'0"E Central African Republic N N " " 0 0 ' Sudan ' 0 0 ° ° 5 5 Z o n g oBangui Mobayi Bosobolo Gbadolite Yakoma Ango Yaounde Bondo Nord Ubangi Niangara Faradje Cameroon Libenge Bas Uele Dungu Bambesa Businga G e m e n a Haut Uele Poko Rungu Watsa Sud Ubangi Aru Aketi B u tt a II s ii rr o r e Kungu Budjala v N i N " R " 0 0 ' i ' g 0 n 0 3 a 3 ° b Mahagi ° 2 U L ii s a ll a Bumba Wamba 2 Orientale Mongala Co Djugu ng o R i Makanza v Banalia B u n ii a Lake Albert Bongandanga er Irumu Bomongo MambasaIturi B a s a n k u s u Basoko Yahuma Bafwasende Equateur Isangi Djolu Yangambi K i s a n g a n i Bolomba Befale Tshopa K i s a n g a n i Beni Uganda M b a n d a k a N N " Equateur " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° Lubero ° 0 Ingende B o e n d e 0 Gabon Ubundu Lake Edward Opala Bikoro Bokungu Lubutu North Kivu Congo Tshuapa Lukolela Ikela Rutshuru Kiri Punia Walikale Masisi Monkoto G o m a Yumbi II n o n g o Kigali Bolobo Lake Kivu Rwanda Lomela Kalehe S S " KabareB u k a v u " 0 0 ' ' 0 Kailo Walungu 0 3 3 ° Shabunda ° 2 2 Mai Ndombe K ii n d u Mushie Mwenga Kwamouth Maniema Pangi B a n d u n d u Bujumbura Oshwe Katako-Kombe South Kivu Uvira Dekese Kole Sankuru Burundi Kas ai R Bagata iver Kibombo Brazzaville Ilebo Fizi Kinshasa Kasongo KasanguluKinshasa Bandundu Bulungu Kasai Oriental Kabambare K e n g e Mweka Lubefu S Luozi L u s a m b o S " Tshela Madimba Kwilu Kasai -

Democratic Republic of Congo: Background and U.S

Democratic Republic of Congo: Background and U.S. Relations name redacted Specialist in African Affairs July 5, 2018 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov R43166 Democratic Republic of Congo: Background and U.S. Relations Summary Since the 2003 conclusion of “Africa’s World War”—a conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) that drew in neighboring countries and reportedly caused millions of deaths—the United States and other donors have focused substantial resources on stabilizing the country. Smaller-scale insurgencies have nonetheless persisted in DRC’s densely-inhabited, mineral-rich eastern provinces, causing regional instability and a long-running humanitarian crisis. In recent years, political uncertainty at the national level has sparked new unrest. Elections due in 2016 have been repeatedly delayed, leaving President Joseph Kabila—who is widely unpopular—in office well past the end of his second five-year term. State security forces have brutally cracked down on anti-Kabila street protests. Armed conflicts have worsened in the east, while new crises have emerged in previously stable areas such as the central Kasai region and southeastern Tanganyika province. An Ebola outbreak in early 2018 added to the country’s humanitarian challenges, although it appears likely to be contained. The Trump Administration has maintained a high-level concern with human rights abuses and elections in DRC. It has simultaneously altered the U.S. approach in some ways by eliminating a senior Special Envoy position created under the Obama Administration and securing a reduction in the U.N. peacekeeping operation in DRC (MONUSCO). The United States remains the largest humanitarian donor in DRC and the largest financial contributor to MONUSCO. -

Who Belongs Where? Conflict, Displacement, Land and Identity in North Kivu, Democratic Republic of Congo

Who Belongs Where? Conflict, Displacement, Land and Identity in North Kivu, Democratic Republic of Congo CITIZENSHIP AND DISPLACEMENT IN THE GREAT LAKES REGION WORKING PAPER NO. 3 MARCH 2010 International Refugee Social Science Rights Initiative Research Council C ITIZENSHIP AND D ISPLACEMENT IN THE G REAT L AKES W ORKING P APER NO. 3 Background to the Paper This paper is the result of a co-ordinated effort between staff from the International Refugee Rights Initiative (IRRI) and the Social Science Research Council (SSRC). The field research was carried out by Joseph Okumu and Kibukila Ben Bonome, and the paper was drafted by Lucy Hovil of IRRI. Deirdre Clancy and Olivia Bueno of IRRI, Josh DeWind of SSRC, and Bronwen Manby of AfriMAP, the Africa Governance Monitoring and Advocacy Project of the Open Society Institute, reviewed and edited the material. The field research team would like to express its gratitude to all those who participated in the study, in particular those displaced by the conflict. Citizenship and Displacement in the Great Lakes Region Working Paper Series The paper is the third in a series of working papers that form part of a collaborative project between the International Refugee Rights Initiative, the Social Science Research Council, and civil society and academic partners in the Great Lakes region. The project seeks to gain a deeper understanding of the linkages between conflicts over citizenship and belonging in the Great Lakes region, and forced displacement. It employs social science research under a human rights framework in order to illuminate how identity affects the experience of the displaced before, during, and after their displacement. -

Kitona Operations: Rwanda's Gamble to Capture Kinshasa and The

Courtesy of Author Courtesy of Author of Courtesy Rwandan Patriotic Army soldiers during 1998 Congo war and insurgency Rwandan Patriotic Army soldiers guard refugees streaming toward collection point near Rwerere during Rwanda insurgency, 1998 The Kitona Operation RWANDA’S GAMBLE TO CAPTURE KINSHASA AND THE MIsrEADING OF An “ALLY” By JAMES STEJSKAL One who is not acquainted with the designs of his neighbors should not enter into alliances with them. —SUN TZU James Stejskal is a Consultant on International Political and Security Affairs and a Military Historian. He was present at the U.S. Embassy in Kigali, Rwanda, from 1997 to 2000, and witnessed the events of the Second Congo War. He is a retired Foreign Service Officer (Political Officer) and retired from the U.S. Army as a Special Forces Warrant Officer in 1996. He is currently working as a Consulting Historian for the Namib Battlefield Heritage Project. ndupress.ndu.edu issue 68, 1 st quarter 2013 / JFQ 99 RECALL | The Kitona Operation n early August 1998, a white Boeing remain hurdles that must be confronted by Uganda, DRC in 1998 remained a safe haven 727 commercial airliner touched down U.S. planners and decisionmakers when for rebels who represented a threat to their unannounced and without warning considering military operations in today’s respective nations. Angola had shared this at the Kitona military airbase in Africa. Rwanda’s foray into DRC in 1998 also concern in 1996, and its dominant security I illustrates the consequences of a failure to imperative remained an ongoing civil war the southwestern Bas Congo region of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).