Japan's Experiences in Public Health and Medical Systems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE Buddhist Thinker and Reformer Nichiren (1222–1282) Is Consid

J/Orient/03 03.10.10 10:55 AM ページ 94 A History of Women in Japanese Buddhism: Nichiren’s Perspectives on the Enlightenment of Women Toshie Kurihara OVERVIEW HE Buddhist thinker and reformer Nichiren (1222–1282) is consid- Tered among the most progressive of the founders of Kamakura Bud- dhism, in that he consistently championed the capacity of women to achieve salvation throughout his ecclesiastic writings.1 This paper will examine Nichiren’s perspectives on women, shaped through his inter- pretation of the 28-chapter Lotus Sutra of Gautama Shakyamuni in India, a version of the scripture translated by Buddhist scholar Kumara- jiva from Sanskrit to Chinese in 406. The paper’s focus is twofold: First, to review doctrinal issues concerning the spiritual potential of women to attain enlightenment and Nichiren’s treatises on these issues, which he posited contrary to the prevailing social and religious norms of medieval Japan. And second, to survey the practical solutions that Nichiren, given the social context of his time, offered to the personal challenges that his women followers confronted in everyday life. THE ATTAINMENT OF BUDDHAHOOD BY WOMEN Historical Relationship of Women and Japanese Buddhism During the Middle Ages, Buddhism in Japan underwent a significant transformation. The new Buddhism movement, predicated on simpler, less esoteric religious practices (igyo-do), gained widespread acceptance among the general populace. It also redefined the roles that women occupied in Buddhism. The relationship between established Buddhist schools and women was among the first to change. It is generally acknowledged that the first three individuals in Japan to renounce the world and devote their lives to Buddhist practice were women. -

Glossary of Japanese Terms

RADAR Research Archive and Digital Asset Repository Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Note if anything has been removed from thesis. Images from page after title page, p74, 95, 99, 116, 122, 149 When referring to this work, the full bibliographic details must be given as follows: Fraser, A. (2012) An investigation of the medical use of thermo-mineral springs found in Misasa (Japan) and Jáchymov (Czech Republic). PhD Thesis. Oxford Brookes University. WWW.BROOKES.AC.UK/GO/RADAR AN INVESTIGATION OF THE MEDICAL USE OF THERMO-MINERAL SPRINGS FOUND IN MISASA (JAPAN) AND JÁCHYMOV (CZECH REPUBLIC) Anna Fraser Department of Social Sciences; Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences This degree is awarded by Oxford Brookes University. This thesis is submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the award of Doctor of Philosophy. Date: October 2012 Y a m a i w a k i k a r a “Illness comes from ki” (Japanese proverb) Abstract This thesis presents an analysis of the beliefs and practices surrounding balneotherapy, a technique that uses waters of natural mineral springs for healing. Balneotherapy as employed in the treatment of mainly chronic, incurable and painful disorders will be used as a tool for revealing the pluralistic medical belief systems in the two cultures chosen for this study, the cultures of Japan and the Czech Republic. -

Social Determinants of Health in Non-Communicable Diseases Case Studies from Japan Springer Series on Epidemiology and Public Health

Springer Series on Epidemiology and Public Health Katsunori Kondo Editor Social Determinants of Health in Non-communicable Diseases Case Studies from Japan Springer Series on Epidemiology and Public Health Series Editors Wolfgang Ahrens, Leibniz Institute for Prevention Research and Epidemiology—BIPS, Bremen, Germany Iris Pigeot, Leibniz Institute for Prevention Research and Epidemiology—BIPS, Bremen, Germany The series has two main aims. First, it publishes textbooks and monographs addressing recent advances in specific research areas. Second, it provides comprehensive overviews of the methods and results of key epidemiological studies marking cornerstones of epidemiological practice, which are otherwise scattered across numerous narrow-focused publications. Thus the series offers in-depth knowledge on a variety of topics, in particular, on epidemiological concepts and methods, statistical tools, applications, epidemiological practice and public health. It also covers innovative areas such as molecular and genetic epidemiology, statistical principles in epidemiology, modern study designs, data management, quality assurance and other recent methodological developments. Written by the key experts and leaders in corresponding fields, the books in the series offer both broad overviews and insights into specific areas and topics. The series serves as an in-depth reference source that can be used complementarily to the “The Handbook of Epidemiology,” which provides a starting point of orientation for interested readers (2nd edition published in 2014 http://www.springer.com/public+health/ book/978-0-387-09835-7). The series is intended for researchers and professionals involved in health research, health reporting, health promotion, health system administration and related aspects. It is also of interest for public health specialists and researchers, epidemiologists, physicians, biostatisticians, health educators, and students worldwide. -

Construction and Verification of the Scale Detection Method for Traditional Japanese Music – a Method Based on Pitch Sequence of Musical Scales –

International Journal of Affective Engineering Vol.12 No.2 pp.309-315 (2013) Special Issue on KEER 2012 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Construction and Verification of the Scale Detection Method for Traditional Japanese Music – A Method Based on Pitch Sequence of Musical Scales – Akihiro KAWASE Department of Corpus Studies, National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics, 10-2 Midori-cho, Tachikawa City, Tokyo 190-8561, Japan Abstract: In this study, we propose a method for automatically detecting musical scales from Japanese musical pieces. A scale is a series of musical notes in ascending or descending order, which is an important element for describing the tonal system (Tonesystem) and capturing the characteristics of the music. The study of scale theory has a long history. Many scale theories for Japanese music have been designed up until this point. Out of these, we chose to formulate a scale detection method based on Seiichi Tokawa’s scale theories for traditional Japanese music, because Tokawa’s scale theories provide a versatile system that covers various conventional scale theories. Since Tokawa did not describe any of his scale detection procedures in detail, we started by analyzing his theories and understanding their characteristics. Based on the findings, we constructed the scale detection method and implemented it in the Java Runtime Environment. Specifically, we sampled 1,794 works from the Nihon Min-yo Taikan (Anthology of Japanese Folk Songs, 1944-1993), and performed the method. We compared the detection results with traditional research results in order to verify the detection method. If the various scales of Japanese music can be automatically detected, it will facilitate the work of specifying scales, which promotes the humanities analysis of Japanese music. -

The Karin Ikebana Exhibition

Sairyuka - Art and ancient Asian philosophy rooted in nature KARIN-en vol.6 Sairyuka No. 35 Supplementary Karin-en News No. 6, January 2018 Ikebana / Paintings / Vessels ... The Karin Ikebana Exhibition Kanazawa / Tokyo “ Ikebana / Paintings / Vessels - The Karin Ikebana Exhibitions” were held in Kanazawa and Tokyo, co- inciding with the Hina festival and Boy’s Day celebration (Sairyuka No. 35). This page and the next show designs from the Tokyo exhibition. Sairyuka - Ikebana of the Wind Camellia (single-variant); by Karin Painting (hanging scroll) - “Sea bream”; by Karin Mounting by Akira Nagashima Vessel: Boat-form ceramic vase and square/circular stand (thick board) Design by Karin Production by Yatomi Maeda (ceramics), Kazuhiko Tada (stand) Koryu Association, Komagome, Tokyo 23 November Held together with the Koryu Ikebana Exhi- bition (continued on p2) Jiyuka (versatile arrangement); by Risei Morikawa Pine, camellia, eucalyptus, lily, soaproot, kori willow, other Vessel: Reika - beech, other; by Box-form ceramic vase Design by Karin Hosei Sakamoto Painting Production by Yatomi Maeda (hanging scroll) - “frog”; by Positioned at the venue entrance Karin Mounting by Akira Na- gashima Vessel: Ceramic “ kagamigata ” (parabolic) vase Design by Karin Production by Yatomi Maeda 1 The Karin Ikebana Exhibition 23 November23 Continued from page page 1 from Continued KoryuAssociation, Komagome, Sairyuka - Five Ikebana: Camellia (single tone) (From left: Wind Ikebana, Water Ikebana, Sword Ikebana, Earth Ikebana, Fire Ikebana): by Karin, Kyuuka Yamaki, Kyuuka Higashimori Paintings (hanging scroll) - From left: Enso-Wind, Enso-Water, Enso-Sword, Enso-Earth, Enso-Fire: Karin Mounting by Akira Nagashima Vessel: Square-circular ceramic vase Design by Karin Tokyo Production by Yatomi Maeda The Tokyo “Karin Ikebana Exhibition” was held on 23 【Right】 November at the Koryu Reika - (Japanese yew), other: by Association in Komagome, Ribin Okamoto alongside the established Painting (hanging scroll) - “sword”; Koryu Shoseikai Ikebana by Karin exhibition. -

Hybrid Identities of Buraku Outcastes in Japan

Educating Minds and Hearts to Change the World A publication of the University of San Francisco Center for the Volume IX ∙ Number 2 June ∙ 2010 Pacific Rim Copyright 2010 The Sea Otter Islands: Geopolitics and Environment in the East Asian Fur Trade >>..............................................................Richard Ravalli 27 Editors Joaquin Gonzalez John Nelson Shadows of Modernity: Hybrid Identities of Buraku Outcastes in Japan Editorial >>...............................................................Nicholas Mucks 36 Consultants Barbara K. Bundy East Timor and the Power of International Commitments in the American Hartmut Fischer Patrick L. Hatcher Decision Making Process >>.......................................................Christopher R. Cook 43 Editorial Board Uldis Kruze Man-lui Lau Syed Hussein Alatas: His Life and Critiques of the Malaysian New Economic Mark Mir Policy Noriko Nagata Stephen Roddy >>................................................................Choon-Yin Sam 55 Kyoko Suda Bruce Wydick Betel Nut Culture in Contemporary Taiwan >>..........................................................................Annie Liu 63 A Note from the Publisher >>..............................................Center for the Pacific Rim 69 Asia Pacific: Perspectives Asia Pacific: Perspectives is a peer-reviewed journal published at least once a year, usually in April/May. It Center for the Pacific Rim welcomes submissions from all fields of the social sciences and the humanities with relevance to the Asia Pacific 2130 Fulton St, LM280 region.* In keeping with the Jesuit traditions of the University of San Francisco, Asia Pacific: Perspectives com- San Francisco, CA mits itself to the highest standards of learning and scholarship. 94117-1080 Our task is to inform public opinion by a broad hospitality to divergent views and ideas that promote cross-cul- Tel: (415) 422-6357 Fax: (415) 422-5933 tural understanding, tolerance, and the dissemination of knowledge unreservedly. -

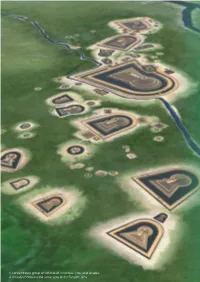

A Concentrated Group of Kofun Built in Various Sizes and Shapes a Virtually Reconstructed Aerial View of the Furuichi Area Chapter 3

A concentrated group of kofun built in various sizes and shapes A virtually reconstructed aerial view of the Furuichi area Chapter 3 Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.1.b Criteria under Which Inscription is Proposed 3.1.c Statement of Integrity 3.1.d Statement of Authenticity 3.1.e Protection and Management Requirements 3.2 Comparative Analysis 3.3 Proposed Statement of Outstanding Universal Value 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis The property “Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group” is a tomb group of the king’s clan and the clan’s affiliates that ruled the ancient Japanese archipelago and took charge of diplomacy with contemporary East Asian powers. The tombs were constructed between the late 4th century and the late 5th century, which was the peak of the Kofun period, characterized by construction of distinctive mounded tombs called kofun. A set of 49 kofun in 45 component parts is located on a plateau overlooking the bay which was the maritime gateway to the continent, in the southern part of the Osaka Plain which was one of the important political cultural centers. The property includes many tombs with plans in the shape of a keyhole, a feature unique in the world, on an extraordinary scale of civil engineering work in terms of world-wide constructions; among these tombs several measure as much as 500 meters in mound length. They form a group, along with smaller tombs that are differentiated by their various sizes and shapes. In contrast to the type of burial mound commonly found in many parts of the world, which is an earth or piled- stone mound forming a simple covering over a coffin or a burial chamber, kofun are architectural achievements with geometrically elaborate designs created as a stage for funerary rituals, decorated with haniwa clay figures. -

Kamakura Period, Early 14Th Century Japanese Cypress (Hinoki) with Pigment, Gold Powder, and Cut Gold Leaf (Kirikane) H

A TEACHER RESOURCE 1 2 Project Director Nancy C. Blume Editor Leise Hook Copyright 2016 Asia Society This publication may not be reproduced in full without written permission of Asia Society. Short sections—less than one page in total length— may be quoted or cited if Asia Society is given credit. For further information, write to Nancy Blume, Asia Society, 725 Park Ave., New York, NY 10021 Cover image Nyoirin Kannon Kamakura period, early 14th century Japanese cypress (hinoki) with pigment, gold powder, and cut gold leaf (kirikane) H. 19½ x W. 15 x D. 12 in. (49.5 x 38.1 x 30.5 cm) Asia Society, New York: Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection, 1979.205 Photography by Synthescape, courtesy of Asia Society 3 4 Kamakura Realism and Spirituality in the Sculpture of Japan Art is of intrinsic importance to the educational process. The arts teach young people how to learn by inspiring in them the desire to learn. The arts use a symbolic language to convey the cultural values and ideologies of the time and place of their making. By including Asian arts in their curriculums, teachers can embark on culturally diverse studies and students will gain a broader and deeper understanding of the world in which they live. Often, this means that students will be encouraged to study the arts of their own cultural heritage and thereby gain self-esteem. Given that the study of Asia is required in many state curriculums, it is clear that our schools and teachers need support and resources to meet the demands and expectations that they already face. -

The Heian Period

A Companion to Japanese History Edited by William M. Tsutsui Copyright © 2007 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd CHAPTER TWO The Heian Period G. Cameron Hurst III Heian is Japan’s classical age, when court power was at its zenith and aristocratic culture flourished. Understandably, it has long been assiduously studied by historians. The Heian period is the longest of the accepted divisions of Japanese history, covering almost exactly 400 years. Its dates seem obvious: ‘‘The Heian period opened in 794 with the building of a new capital, Heian-kyo¯, later known as Kyoto. The Heian period closed in 1185 when the struggle for hegemony among the warrior families resulted in the victory of Minamoto no Yoritomo and most political initiatives devolved into his hands at his headquarters at Kamakura.’’1 Although the establishment of a new capital would seem irrefutable evidence of the start of a new ‘‘period,’’ some argue that the move of the capital from Nara to Nagaoka in 784 better marks the beginning of the era. Indeed, some even consider the accession of Emperor Kammu in 781 a better starting date. Heian gives way to the next period, the Kamakura era, at the end of the twelfth century and the conclusion of the Gempei War. The end dates are even more contested and include (1) 1180 and Taira no Kiyomori’s forced move of the capital to Fukuhara; (2) 1183 and the flight of the Taira from the capital; (3) 1185, the end of the war and Retired Emperor Go-Shirakawa’s confirmation of Minamoto no Yoritomo’s right to appoint shugo and jito¯; or (4) 1192 and Yoritomo’s appointment as sho¯gun. -

JSPS Postdoctoral Fellowships for Research in Japan

List of Fellows Selected through Open Recruitment in Japan Humanities The following list includes the names of the selected fellows, their host researchers and research themes under the 1st recruitment of FY2019-2020 JSPS Postdoctoral Fellowship for Research in Japan (Standard). Under this recruitment, 1127 applications were received, among which 120 fellowships were awarded. Notification of the selection results will be made in writing to the head of the applying institution in December, 2018. An award letter will be sent to the successful candidates in the middle of January, 2019. Unsuccessful candidates are not directly notified of their selection results. However, applicants (host researchers) can see their approximate ranking among all the applications through the JSPS Electronic Application System. Individual requests for selection results are not accepted. Fellow Nationality Host Researcher Host Institution Research Theme Family Name First Name Middle Name KOLODZIEJ Magdalena Patrycia GERMANY Doshin SATO Tokyo University of the Arts Studies of the Imperial Art World of Modern Japan KOWALCZYK Beata Maria POLAND Mitsuyoshi NUMANO The University of Tokyo Nihon no sakka: Constructing Literary Careers in the Japanese Literary World ROH Junia KOREA Seishi NAMIKI Kyoto Institute of Technology A Study on the Invention of Locality of Japanese Craft in Meiji era (REP. OF KOREA) JAMMO Sari SYRIA Yoshihiro NISHIAKI The University of Tokyo Investigating human behavior during the Neolithization intra/beyond the Fertile Crescent SIM Jeongmyoung -

A History of Tuberculosis in Occupied Japan by Bailey

THE INHERITED EPIDEMIC: A HISTORY OF TUBERCULOSIS IN OCCUPIED JAPAN BY BAILEY KIRSTEN ALBRECHT THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in East Asian Studies in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2014 Urbana, Illinois Master’s Committee: Assistant Professor Roderick Wilson, Chair Associate Professor Robert Tierney Professor Leslie Reagan ABSTRACT Scholarship on Japan’s Occupation Period (1945-1952) has focused on the ways in which Japan was transformed from an imperial power to a democratic nation. While such work provides valuable information about how the Supreme Commanders for the Allied Powers (SCAP) affected Japan’s political climate following the end of the Asia- Pacific War, they gloss over other ways in which the SCAP government came in contact with the Japanese people. The topic of health is one that has seldom been explored within the context of the Allied Occupation of Japan, despite the fact that the task of restoring and maintaining health brought SCAP personnel and policies into daily contact with both the Japanese government and people. By focusing on the disease tuberculosis, which boasted the highest mortality rate not only during the Occupation Period, but also for most of the first-half of the twentieth century, this paper hopes to illuminate the ways in which health brought the Allied Powers and Japanese into constant contact. The managing of tuberculosis in the Occupation Period represented a major success for SCAP’s Public Health and Welfare (PH&W) section. The new medical findings, medicines, and management and education systems that the PH&W incorporated into the Japanese health systems played a large role in the PH&W’s success in controlling tuberculosis within Japan. -

JAPAN for ASIA Occupational Safety and Health the Rapid Economic Growth of Japan Has Been Supported by Workers

For People, Life and Future Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare JAPAN for ASIA Occupational Safety and Health The rapid economic growth of Japan has been supported by workers. Meanwhile, many of the experienced workers who supported the economic growth and young people who were about to support development in the future have lost their lives due to various occupational accidents at construction sites and factories, and occupational diseases caused by asbestos, chemical substances including bladder cancer. Based on the experience and the knowledge that Japan has learned from the past, we would like to contribute to the sound economic development in developing countries by considering occupational safety and health, taking necessary actions and practicing measures together with the people in the country. We believe such cooperation is an important contribution of Japan in the international society, which promotes human security and development of human resources. History of Occupational Safety and Health in Japan (main items) 1950’s ●Along with post-war reconstruction, rash of silicosis in metal/coal mines, pneumoconiosis in manufacturing industry → Law on Special Protection Measures concerning Silicosis, etc. (1955), Pneumoconiosis Law (1960) ●Response to radiation hazards by nuclear power development and non-destructive inspection technology → Regulation on Prevention of Ionizing Radiation Hazards (1959) ●Onset of aplastic anemia due to benzene contained rubber glue at sandal factory → Regulation on Prevention of Organic Solvent Intoxication