Sarasvatī. Riverine Goddess of Knowledge. from the Manuscript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

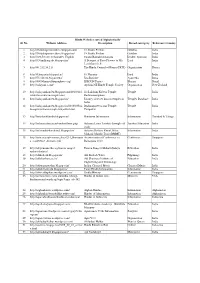

3.Hindu Websites Sorted Country Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Country wise Sl. Reference Country Broad catergory Website Address Description No. 1 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindushahi Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 2 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jayapala King Jayapala -Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 3 Afghanistan Dynasty http://www.afghanhindu.com/history.asp The Hindu Shahi Dynasty (870 C.E. - 1015 C.E.) 4 Afghanistan History http://hindutemples- Hindu Roots of Afghanistan whthappendtothem.blogspot.com/ (Gandhar pradesh) 5 Afghanistan History http://www.hindunet.org/hindu_history/mode Hindu Kush rn/hindu_kush.html 6 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindu.wordpress.com/ Afghan Hindus 7 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindusandsikhs.yuku.com/ Hindus of Afaganistan 8 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.com/vedic.asp Afghanistan and It's Vedic Culture 9 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.de.vu/ Hindus of Afaganistan 10 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.afghanhindu.info/ Afghan Hindus 11 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.asamai.com/ Afghan Hindu Asociation 12 Afghanistan Temple http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindu_Temples_ Hindu Temples of Kabul of_Kabul 13 Afghanistan Temples Database http://www.athithy.com/index.php?module=p Hindu Temples of Afaganistan luspoints&id=851&action=pluspoint&title=H indu%20Temples%20in%20Afghanistan%20. html 14 Argentina Ayurveda http://www.augurhostel.com/ Augur Hostel Yoga & Ayurveda 15 Argentina Festival http://www.indembarg.org.ar/en/ Festival of -

2.Hindu Websites Sorted Category Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Category wise Sl. No. Broad catergory Website Address Description Reference Country 1 Archaelogy http://aryaculture.tripod.com/vedicdharma/id10. India's Cultural Link with Ancient Mexico html America 2 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa Harappa Civilisation India 3 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civil Indus Valley Civilisation India ization 4 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kiradu_temples Kiradu Barmer Temples India 5 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohenjo_Daro Mohenjo_Daro Civilisation India 6 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nalanda Nalanda University India 7 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxila Takshashila University Pakistan 8 Archaelogy http://selians.blogspot.in/2010/01/ganesha- Ganesha, ‘lingga yoni’ found at newly Indonesia lingga-yoni-found-at-newly.html discovered site 9 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Ancient Idol of Lord Vishnu found Russia om/2012/05/27/ancient-idol-of-lord-vishnu- during excavation in an old village in found-during-excavation-in-an-old-village-in- Russia’s Volga Region russias-volga-region/ 10 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Mahendraparvata, 1,200-Year-Old Cambodia om/2013/06/15/mahendraparvata-1200-year- Lost Medieval City In Cambodia, old-lost-medieval-city-in-cambodia-unearthed- Unearthed By Archaeologists 11 Archaelogy http://wikimapia.org/7359843/Takshashila- Takshashila University Pakistan Taxila 12 Archaelogy http://www.agamahindu.com/vietnam-hindu- Vietnam -

1.Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

Use Style: Paper Title

The 2015 WEI International Academic Conference Proceedings Athens, Greece LINKING RELIGIONS WITH TRADE NETWORKS AND THEIR MARKETING INFRASTRUCTURE IN ASIA1 Ruchi Agarwal Mahidol University International College Nakorn Pathom, Thailand Abstract Number of researches outlines the relations between religions and trade but few focused on the two-way relationship shared between religions and trade networks and the role of marketing infrastructure in facilitating this relationship. This article aims to fill this gap by examining the role of trade networks in the dissemination of Buddhism and Hinduism in China and Southeast Asia and how these religions facilitated trade networks in expanding their businesses. Historical data reveals a strong link between the two and marketing made an important contribution in developing these links further. Contemporary data on the basis of supply-side theory shows new marketing strategies introduced in religious marketplace leading to commodification of religions with an emphasis religiosity in Thailand as a case study. Keywords: Buddhism, China, Hinduism, India, Markets, Religious dissemination, Southeast Asia, Trade I. INTRODUCTION This paper aims to study the role of trade networks in the dissemination of religions and vise versa by focusing on two religions, Buddhism and Hinduism both originating in India. In this paper, I argue that religious dissemination and trade networks share strong links and marketing infrastructure plays an important role in facilitating this link. To support my argument two examples of a historical linkage between religions and trade will be provided before focusing on more of the contemporary developments. One focuses on how the dissemination of Buddhism in China linked two very diverse regions together and the second focuses on Hinduism travelling to Southeast Asia, largely a function of South Asian migration. -

The Hindu Temple in China

2019 International Conference on Humanities, Cultures, Arts and Design (ICHCAD 2019) The Hindu Temple in China Xubiao Yang College of Marxism Studies, Guizhou University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Guiyang, Guizhou, China Keywords: Hindu temple, China, Silk road, Border and coastal areas Abstract: With the spread of Hinduism, the Hindu temple was introduced into China. The Hindu temple was introduced into China mainly through the Overland Silk Road and the Maritime Silk Road, the Hindu temples in border and coastal areas of Chinese territory were mainly patronized by wealthy individuals and commercial guilds. The Hindu temple was localized and assiminated in the coures of spread and gradually became an integral part of Chinese architecture culture. 1. Introduction The Hindu temple is the abobe of gods on earth, it links the world of man and the world of the gods. The Hindu temple is essential to understand the Indian culure, art, economy, politics, etc. A Hindu temple incorporates all elements of Hinduism- symbolism, cosmology, the goals of life, the caste system and henceon. In the course of history, with the spread of Hinduism to alien lands, the Hindu templ architecture was alhencespread to many regions and countries outside the South Asia Subcontinent.And China was one of these regions and countries, the Hindu temples in Chinese territory built by Indian immigrants and merchants witness the cultural exchange between Indian and China. 2. The Spread of Hinduism to China Hinduism was introduced into China around the first century AD when the Indian immigrates and merchants migrated to some border areas and coastal cities of the Chinese territory. -

India-Japan Cultural Syncretism Reflected in Japanese Pantheon of Deities Siddharth Singh Director, Vivekananda Cultural Centre

India-Japan Cultural syncretism reflected in Japanese Pantheon of deities Siddharth Singh Director, Vivekananda Cultural Centre, Embassy of India, Tokyo “India is culturally, Mother of Japan. For centuries it has, in her own characteristic way, been exercising her influence on the thought and culture of Japan. …..without Indian influence, Japanese culture would not be what it is today. As most Japanese profess the Buddhist faith, needless to say, they have generally been influenced by Indian ideas to a great extent.” [1] Hajime Nakamura “It is very important for the Japanese to know that in the bottom of Japanese culture, Indian culture is very firmly imprinted.”[2] Yasukuni Enoki, Former Ambassador of Japan to India It is pertinent to know how closely Indian culture is embedded in the Japanese past and present and a bright example of such deeper linkages is Japanese temples containing the statues of various deities. Numerous major and minor deities, ubiquitously present in Japanese temples, have their origin in the ancient Indian pantheon of gods and goddesses, but since these deities were introduced to Japan via China with Chinese names, Japanese people, in most of the cases, are unaware of their origins. There are well-theorized claims that establish the introduction of Indian culture to Japan even before the formal introduction of Buddhism from Korea in 552 CE. According to the Book of Liang, which was written in 635, five Buddhist monks from the Gandhara region of India traveled to Japan during the Kofun period (250-538 CE) in 467 CE. [3] After the arrival of Buddhism, Aryadhamma, a Buddhist monk from Rajgriha (Bihar, India) seems to have entered Japan via China in 645 CE,[4] much before Bodhisena’s arrival at Naniwa (Osaka). -

Seven Lucky Gods of Japan

Seven Lucky Gods of Japan The Treasure Ship and the Seven Lucky Gods From bottom left: Daikokuten (with magic mallet), Fukurokuju (with large head), Bishimonten (in helmet), Benten (with lute), Ebisu (with fish), Jurojin (with white beard) and Hotei (with treasure sack) The Shichifukujin 七福神 are an eclectic group of deities from Japan, India, and China. Only one is native to Japan (Ebisu) and Japan’s indigenous Shint, tradition. Three are deva from India’s Hindu pantheon (Benzaiten, Bishamonten, Daikokuten) and three are gods from China’s Taoist-Buddhist traditions (Fukurokuju, Hotei, Jur,jin). Each deity existed independently before Japan’s “artificial” creation of the group. The origin of the group is unclear, although most scholars point to the Muromachi era (1392-1568) and the late 15th century. By the 19th century, most major cities had developed special pilgrimage circuits for the seven. These pilgrimages remain well trodden in contemporary times, but many people now use cars, buses, and trains to move between the sites. Today images of the seven appear with great frequency in Japan. In one popular Japanese tradition, they travel together on their treasure ship (Takarabune 宝船 ) and visit human ports on New Year’s Eve to dispense happiness to believers. Children are told to place a picture of this ship (or of Baku, the nightmare eater) under their pillows on the evening of January first. Local custom says if they have a good dream that night, they will be lucky for the whole year. Ebisu: origin Japan. God of the Ocean, Fishing Folk, Good Fortune, Honest Labor, Commerce. -

Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically Sl

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

The Analects Online

4s9bv (Download pdf) The Analects Online [4s9bv.ebook] The Analects Pdf Free Confucius *Download PDF | ePub | DOC | audiobook | ebooks Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #886013 in Books 2016-09-13Original language:English 9.02 x .44 x 5.98l, #File Name: 1613827865138 pages | File size: 79.Mb Confucius : The Analects before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Analects: 3 of 3 people found the following review helpful. Itrsquo;s packed with a lot of great gems!By Brian Johnson[[VIDEOID:89c7d4bfd017d8efb0e43c5f6d6bd237]] ldquo;For those who approve but do not carry out, who are stirred, but do not change, I can do nothing at all.rdquo;ldquo;The Master said, To men who have risen at all above the middling sort, one may talk of things higher yet. But to men who are at all below the middling sort it is useless to talk of things that are above them.rdquo;ldquo;As to be being a Divine Sage or even a Good Man, far be it from me to make any such claim. As for unwavering effort to learn and unflagging patience in teaching others, those are merits that I do not hesitate to claim.rdquo;~ Confucius from The Analects of ConfuciusWersquo;re going old school on this one.Believed to be rockinrsquo; it in the 5th/6th century BCE (around the same time as Lao Tzu and Buddha), Confucius was super passionate about learning and developing himself into the best person he could be according to the dictates of his classic society.The book can get a little funny as Confucius goes into some detail on how to live properly according to ancient Chinese customs (donrsquo;t forget to wear the black silk on special occasions! :) but itrsquo;s packed with a lot of great gems.Here are some of the Big Ideas:1. -

Ancient China 4 Cover Story

Dubai's The Beatles Yogathon 44 Let it Be in India 32 Ethics Culture Philosophy Meditation Vastu Religion Panchang Issue No. 61 June 2013 Price: 2.95 ISSN 2040-1825 Krishna and Shiva Worship in Ancient China 4 Cover Story Native India 12 g y .or Hindus of Ethics .hindutoday Histor www Guyana 27 of Life 43 Editorial EDITOR-IN-CHIEF : ARJAN VEKARIA PUBLISHER : PANNA VEKARIA LEGAL CONSULTANT : VIJAY GOEL USA EDITOR : VRNDAVAN BRANNON PARKER AFRICA EDITOR : MULJIBHAI PINDOLIA Native India VASTU EDITOR : CORALIE FELICITAS SRIVASTAVA n this edition of Hindu Today we are shining the light EDITORIAL, ADVERTISEMENT & CIRCULATION : upon both the past and present scenario of Hinduism VASCROFT ESTATE,861, CORONATION ROAD, I PARK ROYAL, LONDON,NW 107 PT in India and around the world. Our cover story details TEL: + 44(0) 20 8961 8928 the presence of Hinduism in ancient China. Significant FAX : +44(0) 20 8961 8928 discoveries have been made confirming the popularity EMAIL : [email protected] [email protected] of many Vedic deities and Temples that once dotted the Chinese landscape. HINDU TODAY PUBLISHED BY As the two giants of Asia and the world's largest and PANNA VEKARIA VASCROFT ESTATE,861, CORONATION ROAD, ongoing civilizations, it is hoped that these ancient links PARK ROYAL, LONDON,NW 107 PT will complement the well-known Buddhist commonal- ity between China and India. These two nations repre- PRINTED BY rd EVOLUTION PRINT & DESIGN LTD. UNIT 12 sent one 3 of Humanity and many solutions to our LEWISHER ROAD, LEICESTER LE4 9LR modern conundrums can be found within these traditions and culture. -

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 30/1-2 (2003) Divinity Daikokuten (Sk

REVIEWS | 177 Iyanaga Nobumi 彌永信美,Daikokuten henso: Bukkyd shinwagaku I 大黒天変相一 仏教神話学I Kyoto: Hozokan, 2002. x + 651 d d ., including bioiiography and motif/deity/place name/personal mme/Daizdkyo reference indexes. ¥14,000 cloth, i s b n 4-8318-7671-2. 響寒譚 Iyanaga Nobumi, Kannon henydtan: Bukkyd smnwagaku II 観音変容譚ー仏教神話学II _ Kyoto: Hozokan, 2002. ix + 769 pp.,including bioliography and same set of indexes as Volume 1. ¥18,000 cloth, i s b n 4-8318- 7672-0. This set of w orks constitutes the first serious attempt ever conducted to develop an approach to Buddhist studies that the author calls “Buddhist mythology.” Iyanaga Nobumi, who previously studied under Rolf A. Stein of the College de France, offers an elaborate study of mythological representations of the Buddhist 178 | Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 30/1-2 (2003) divinity Daikokuten (Sk. Mahakala) and bodhisattva Kannon (Sk. Avalokitesvara) throughout Asia to attempt to demonstrate not merely that Buddhist art, architec ture, and literature included a developed mythology but that Buddhist mythology should constitute a basic approach within Buddhist studies. It would be an understatement to call these works a “great read.” Beginning with the Introduction to the first volume, I realized that I was reading work that tran scends academic scholarship. While, as I will later explain, such a condition does at points prevent the level of meticulous analysis ideal to academic works, Iyanaga has spent these past 15 years or so drawing together an impressive compendium of sources into a narrative that is irresistibly engaging. Iyanaga’s use of the Japanese language can only be compared with the great scholars of Japanese literary-religious studies, figures such as Abe Yasuro in our era; it is clear that he has spent much of the time in writing these works not only in analyzing the works at hand but also in carefully constructing a discipline in convincing as well as edifying language. -

Shichi Fukujin – Seven Gods of Luck and Good Fortune

Shichi Fukujin – Seven Gods of Luck and Good Fortune (Ritual researched, written and presented by Maria in Sydney and presented by Samantha in Nowra on Friday 5th December 2014.) Shichi Fukujin: are the Seven Gods of Luck and Good Fortune in Japan. Shichi means seven, fuku means luck, and jin means god Each one of them symbolizes a virtue: Honesty, Fortune, Dignity. Amiability, Longevity, Happiness and Wisdom. The Seven Lucky Gods of Japan are an eclectic group of popular deities whose origins stem from Indian, Chinese and Japanese gods of fortune and settled in Japanese Folklore Gods. They were chosen from Hinduism, Buddhism, Taoist and Shinto gods or saints, and believed to have been grouped together around 17th century. Japan (Ebisu), Shinto Tradition India (Daikokuten, Bishamonten, and Benzaiten) Hindu Pantheon China (Hotei, Jurojin, and Fukurokuju). Taoist – Buddhist Traditions According to the Japanese legend, they travel in a ship called Takarabune which is filled with treasures and comes from sea to bring fortune and prosperity to everyone. It is said that if you leave a picture of the Shichi Fukujin below your pillow on the night of the last day of the year, you will be lucky and have good fortune the whole New Year The Seven Gods of Luck and Good Fortune are: Ebisu 恵比須 Also known as Yebisu, he is the God of Fishing, Shipping and Commerce and is the only one to have his origins in Japan. Ebisu is very popular among the people who works in the food industry (farmers and sailors) as is commonly presented wearing formal court clothes or hunting robes.