196-227 Welt Sum 09.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Georgia's October 2013 Presidential Election: Outcome and Implications

Georgia’s October 2013 Presidential Election: Outcome and Implications Jim Nichol Specialist in Russian and Eurasian Affairs November 4, 2013 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R43299 Georgia’s October 2013 Presidential Election: Outcome and Implications Summary This report discusses Georgia’s October 27, 2013, presidential election and its implications for U.S. interests. The election took place one year after a legislative election that witnessed the mostly peaceful shift of legislative and ministerial power from the ruling party, the United National Movement (UNM), to the Georgia Dream (GD) coalition bloc. The newly elected president, Giorgi Margvelashvili of the GD, will have fewer powers under recently approved constitutional changes. Most observers have viewed the 2013 presidential election as marking Georgia’s further progress in democratization, including a peaceful shift of presidential power from UNM head Mikheil Saakashvili to GD official Margvelashvili. Some analysts, however, have raised concerns over ongoing tensions between the UNM and GD, as well as Prime Minister and GD head Bidzini Ivanishvili’s announcement on November 2, 2013, that he will step down as the premier. In his victory speech on October 28, Margvelashvili reaffirmed Georgia’s Euro-Atlantic foreign policy orientation, including the pursuit of Georgia’s future membership in NATO and the EU. At the same time, he reiterated that GD would continue to pursue the normalization of ties with Russia. On October 28, 2013, the U.S. State Department praised the Georgian presidential election as generally democratic and expressing the will of the people, and as demonstrating Georgia’s continuing commitment to Euro-Atlantic integration. -

INTERNATIONAL ELECTION OBSERVATION MISSION Georgia — Municipal Elections, 30 May 2010

INTERNATIONAL ELECTION OBSERVATION MISSION Georgia — Municipal Elections, 30 May 2010 STATEMENT OF PRELIMINARY FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS PRELIMINARY CONCLUSIONS The 30 May municipal elections marked evident progress towards meeting OSCE and Council of Europe commitments. However, significant remaining shortcomings include deficiencies in the legal framework, its implementation, an uneven playing field, and isolated cases of election-day fraud. The authorities and the election administration made clear efforts to pro-actively address problems. Nevertheless, the low level of public confidence persisted. Further efforts in resolutely tackling recurring misconduct are required in order to consolidate the progress and enhance public trust before the next national elections. While the elections were overall well administered, systemic irregularities on election day were noted, as in past elections, in particular in Kakheti, Samtskhe-Javakheti and Shida Kartli. The election administration managed these elections in a professional, transparent and inclusive manner. The new Central Election Commission (CEC) chairperson tried to reach consensus among CEC members, including those nominated by political parties, on all issues. For the first time, Precinct Election Commission (PEC) secretaries were elected by opposition-appointed PEC members, which was welcomed by opposition parties and increased inclusiveness. The transparency of the electoral process was enhanced by a large number of domestic observers. Considerable efforts were made to improve the quality of voters’ lists. In the run-up to these elections, parties received state funding to audit the lists. Voters were given sufficient time and information to check their entries. As part of the recent UEC amendments, some restrictions were placed on the rights of certain categories of citizens to vote in municipal elections, in order to address opposition parties’ concerns of possible electoral malpractices. -

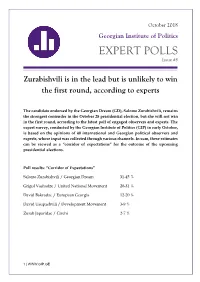

EXPERT POLLS Issue #8

October 2018 Georgian Institute of Politics EXPERT POLLS Issue #8 Zurabishvili is in the lead but is unlikely to win the first round, according to experts The candidate endorsed by the Georgian Dream (GD), Salome Zurabishvili, remains the strongest contender in the October 28 presidential election, but she will not win in the first round, according to the latest poll of engaged observers and experts. The expert survey, conducted by the Georgian Institute of Politics (GIP) in early October, is based on the opinions of 40 international and Georgian political observers and experts, whose input was collected through various channels. In sum, these estimates can be viewed as a “corridor of expectations” for the outcome of the upcoming presidential elections. Poll results: “Corridor of Expectations” Salome Zurabishvili / Georgian Dream 31-45 % Grigol Vashadze / United National Movement 20-31 % David Bakradze / European Georgia 12-20 % David Usupashvili / Development Movement 3-9 % Zurab Japaridze / Girchi 2-7 % 1 | WWW.GIP.GE Figure 1: Corridor of expectations (in percent) Who is going to win the presidential election? According to surveyed experts (figure 1), Salome Zurabishvili, who is endorsed by the governing Georgian Dream party, is poised to receive the most votes in the upcoming presidential elections. It is likely, however, that she will not receive enough votes to win the elections in the first round. According to the survey, Zurabishvili’s vote share in the first round of the elections will be between 31-45%. She will be followed by the United National Movement (UNM) candidate, Grigol Vashadze, who is expected to receive between 20-31% of votes. -

Russia-Georgia Relations

russian analytical russian analytical digest 68/09 digest the moment. So are specific steps aimed at resolving the usually are not focused on activities that cannot bring Abkhazia and South Ossetia conflicts. Harm reduction anything tangible in the short run. is the only realistic policy objective in that area. As to the long run, one should admit that nobody At the same time, Georgia cannot afford to lose ties can confidently predict what will be happening in the to the people who live in Abkhazia and South Ossetia region in ten–fifteen years time or beyond that. Georgia now – whatever political attitudes they may have. This has too much on its hands right now to be too involved is not easy, but Georgians – both in government and in speculations about it. It is rational to focus on ob- in society – should be creative and inventive on this jectives that can be achieved and not allow things that point. Apart from technical impediments for such con- cannot be changed for the time being to get one de- tacts, the trick is that there can be no short-term politi- pressed. cal advantages coming from such contacts, and people About the Author: Professor Ghia Nodia is the Director of the School of Caucasus Studies at Ilia Chavchavadze State University in Tbilisi, Georgia and chairman of the Caucasus Institute for Peace, Democracy and Development, a Georgian think-tank. Georgian Attitudes to Russia: Surprisingly Positive By Hans Gutbrod and Nana Papiashvili, Tbilisi Abstract What do Georgians think about Russia? What relationship would they like to have with their northern neighbor? And what do they think about the August conflict? Data collected by the Caucasus Research Resource Center (CRRC) allows a nuanced answer to these questions: although Georgians have a very crit- ical view of Russia’s role in the August conflict, they continue to desire a good political relationship with their northern neighbor, as long as this is not at the expense of close ties with the West. -

Georgia's 2008 Presidential Election

Election Observation Report: Georgia’s 2008 Presidential Elections Election Observation Report: Georgia’s saarCevno sadamkvirveblo misiis saboloo angariSi angariSi saboloo misiis sadamkvirveblo saarCevno THE IN T ERN at ION A L REPUBLIC A N INS T I T U T E 2008 wlis 5 ianvari 5 wlis 2008 saqarTvelos saprezidento arCevnebi saprezidento saqarTvelos ADV A NCING DEMOCR A CY WORLD W IDE demokratiis ganviTarebisTvis mTel msoflioSi mTel ganviTarebisTvis demokratiis GEORGI A PRESIDEN T I A L ELEC T ION JA NU A RY 5, 2008 International Republican Institute saerTaSoriso respublikuri instituti respublikuri saerTaSoriso ELEC T ION OBSERV at ION MISSION FIN A L REPOR T Georgia Presidential Election January 5, 2008 Election Observation Mission Final Report The International Republican Institute 1225 Eye Street, NW, Suite 700 Washington, DC 20005 www.iri.org TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction 3 II. Pre-Election Period 5 A. Political Situation November 2007 – January 2008 B. Presidential Candidates in the January 5, 2008 Presidential Election C. Campaign Period III. Election Period 11 A. Pre-Election Meetings B. Election Day IV. Findings and Recommendations 15 V. Appendix 19 A. IRI Preliminary Statement on the Georgian Presidential Election B. Election Observation Delegation Members C. IRI in Georgia 2008 Georgia Presidential Election 3 I. Introduction The January 2008 election cycle marked the second presidential election conducted in Georgia since the Rose Revolution. This snap election was called by President Mikheil Saakashvili who made a decision to resign after a violent crackdown on opposition street protests in November 2007. Pursuant to the Georgian Constitution, he relinquished power to Speaker of Parliament Nino Burjanadze who became Acting President. -

Georgia: What Now?

GEORGIA: WHAT NOW? 3 December 2003 Europe Report N°151 Tbilisi/Brussels TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................. 2 A. HISTORY ...............................................................................................................................2 B. GEOPOLITICS ........................................................................................................................3 1. External Players .........................................................................................................4 2. Why Georgia Matters.................................................................................................5 III. WHAT LED TO THE REVOLUTION........................................................................ 6 A. ELECTIONS – FREE AND FAIR? ..............................................................................................8 B. ELECTION DAY AND AFTER ..................................................................................................9 IV. ENSURING STATE CONTINUITY .......................................................................... 12 A. STABILITY IN THE TRANSITION PERIOD ...............................................................................12 B. THE PRO-SHEVARDNADZE -

PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION in GEORGIA 27Th October 2013

PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION IN GEORGIA 27th October 2013 European Elections monitor The candidate in office, Giorgi Margvelashvili, favourite in the Presidential Election in Georgia Corinne Deloy Translated by Helen Levy On 27th October next, 3,537,249 Georgians will be electing their president of the republic. The election is important even though the constitutional reform of 2010 deprived the Head of State of some of his powers to be benefit of the Prime Minister and Parliament (Sakartvelos Parlamenti). The President of the Republic will no longer be able to dismiss the government and convene a new Analysis cabinet without parliament’s approval. The latter will also be responsible for appointing the regional governors, which previously lay within the powers of the President of the Republic. The constitutional reform which modified the powers enjoyed by the head of State was approved by the Georgian parliament on 21st March last 135 votes in support, i.e. all of the MPs present. The outgoing President, Mikheil Saakashvili (United National Movement, ENM), in office since the election on 4th January 2004 cannot run for office again since the Constitution does not allow more than two consecutive mandates. Georgian Dream-Democratic Georgia in coalition with Mikheil Saakashvili. 10 have been appointed by politi- Our Georgia-Free Democrats led by former representa- cal parties, 13 by initiative groups. 54 people registe- tive of Georgia at the UN, Irakli Alasania, the Republi- red to stand in all. can Party led by Davit Usupashvili, the National Forum The candidates are as follows: led by Kakha Shartava, the Conservative Party led by Zviad Dzidziguri and Industry will save Georgia led by – Giorgi Margvelashvili (Georgian Dream-Democratic Prime Minister Bidzina Ivanishvili has been in office Georgia), former Minister of Education and Science and since the general elections on 1st October 2012. -

Proverb As a Tool of Persuasion in Political Discourse (On the Material of Georgian and French Languages)

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 10, No. 6, pp. 632-637, June 2020 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/tpls.1006.02 Proverb as a Tool of Persuasion in Political Discourse (on the Material of Georgian and French languages) Bela Glonti School of Arts and Sciences, Ilia State University, Tbilisi, Georgia; The Francophone Regional Doctoral College of Central and Eastern Europe in the Humanities (CODFREURCOR), Georgia Abstract—Our study deals with the use of proverbs as a tool of persuasion in political discourse. Within this study we have studied and analyzed the texts of Georgian and French political articles, speeches and proverbs used therein. The analysis revealed that the proverbs found and used by us in the French discourses were not only of French origin. Also, most of the proverbs found in the French discourses were used as titles of the articles. As for the Georgian proverbs, they consisted mainly of popular proverbs well known to the Georgian public. Georgia proverbs have rarely been cited as an article title. According to the general conclusion, the use of proverbs as a tool of persuasion in the political discourse by the politicians of both countries is quite relevant. It is effective when it is persuasive and at the same time causes an emotional reaction. Quoting the proverbs, the politicians base their thinking on positions. The proverb is one of the key argumentative techniques. Index Terms—proverb, translation, culture, argumentation I. INTRODUCTION The article is concerned with a proverb, as a tool of persuasion in Georgian and French political discourse. -

Tbilisi Architecture at the Intersection of Continents

Tbilisi Architecture at the Intersection of Continents From 10 March until 27 April 2016 Concept: Adolph Stiller Exhibition venue: Exhibition Centre in the Ringturm 1010 Vienna, Schottenring 30 Opening hours: Monday to Friday, 9 am to 6 pm, free admission (closed on public holidays as well as 25 March 2016) Press tour: Wednesday, 9 March 2016, 4 pm Speakers: Irina Kurtishvili, Rostyslaw Bortnyk, Adolph Stiller Official Opening Wednesday, 9 March 2016, 6.30 pm (by invitation only) Enquiries to: Romy Schrammel T: +43 (0)50 350-21224 F: +43 (0)50 350 99-21224 E-Mail: [email protected] Free press photos are available for download at http://go.picturedesk.com/ElaVKAiP WIENER STÄDTISCHE WECHSELSEITIGER VERSICHERUNGSVEREIN – VERMÖGENSVERWALTUNG – VIENNA INSURANCE GROUP Ringturm, Schottenring 30, PO Box 80, A-1011 Vienna Mutual insurance company with a registered office in Vienna; Commercial Court of Vienna; FN 101530 i; DVR no 0688533; VAD ID no ATU 15363309 Tbilisi – architecture at the crossroads of Europe and Asia The name Tbilisi is derived from the old Georgian word “tbili”, which roughly translates as “warm” and refers to the region’s numerous hot sulphur springs that reach temperatures of up to 47°C. The area was first settled in the early Bronze Age, and ancient times also left their mark: in Greek mythology, the Argonauts sailed to Colchis, which was part of Georgia, in their quest for the Golden Fleece. In the fifth century King Vakhtang I Gorgasali turned the existing settlement into a fortified town, and in the first half of that century Tbilisi was recognised as the second capital of the kings of Kartli in eastern Georgia. -

Who Owned Georgia Eng.Pdf

By Paul Rimple This book is about the businessmen and the companies who own significant shares in broadcasting, telecommunications, advertisement, oil import and distribution, pharmaceutical, privatisation and mining sectors. Furthermore, It describes the relationship and connections between the businessmen and companies with the government. Included is the information about the connections of these businessmen and companies with the government. The book encompases the time period between 2003-2012. At the time of the writing of the book significant changes have taken place with regards to property rights in Georgia. As a result of 2012 Parliamentary elections the ruling party has lost the majority resulting in significant changes in the business ownership structure in Georgia. Those changes are included in the last chapter of this book. The project has been initiated by Transparency International Georgia. The author of the book is journalist Paul Rimple. He has been assisted by analyst Giorgi Chanturia from Transparency International Georgia. Online version of this book is available on this address: http://www.transparency.ge/ Published with the financial support of Open Society Georgia Foundation The views expressed in the report to not necessarily coincide with those of the Open Society Georgia Foundation, therefore the organisation is not responsible for the report’s content. WHO OWNED GEORGIA 2003-2012 By Paul Rimple 1 Contents INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................................3 -

Misuse of Administrative Resources During Georgia's 2020

Misuse of Administrative Resources during Georgia’s 2020 Parliamentary Elections Final Report December 2020 Authors Gigi Chikhladze Tamta Kakhidze Co-author and research supervisor Levan Natroshvili This report was made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The opinions expressed in the report belong to Transparency International Georgia and may not reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. Contents Key Findings ____________________________________________________________________ 4 Introduction ____________________________________________________________________ 7 Chapter I. What is the misuse of administrative resources during electoral processes? ____________________________________________________________________ 8 Chapter II. Misuse of Enforcement Administrative Resources during Electoral Processes ____________________________________________________________________ 9 1. Violence, threatening, intimidation, and law enforcement response _________ 10 1.1. Incidents that occurred during the pre-election period _____________________ 10 1.2. Incidents that occurred during the Election Day ____________________________ 14 1.3. Incidents that occurred after the Election Day ____________________________ 15 2. Destruction of political party property and campaigning materials and law enforcement response to them _________________________________________________ 15 3. Use of water cannons against demonstrators gathered at the CEC ___________ 16 4. -

The EU's Eastern Policy in Light of the Georgian Conflict and the Gas

The EU’s Eastern Policy in light of the Georgian Conflict and the Gas War Abstract The EU is seeking to develop its relations with former ex-Soviet republics at a time of growing Russian opposition to the expansion of Western influence into what it considers its sphere of influence, coupled with increased tensions between Russia and some of the other former Soviet states. The EU should not accept the concept of a Russian sphere of influence in Eastern Europe. The circumstances leading to the Second World War and the Cold War have made it clear that the same principles of international law, and national sovereignty, must apply throughout the continent. Furthermore, the Georgian conflict and the Russo-Ukrainian gas war have shown that the state of Russia’s relations with its neighbours can adversely affect EU interests. Furthermore, there is a danger of a renewal of the Georgia conflict and of further interruptions of the Russian gas transiting Ukraine. The EU should therefore make the state of Russia’s relations with its neighbours a factor in the EU’s co-operation with Russia. For the EU to influence most effectively Russian policy, and for the EU to develop its relations with the other former Soviet republics without Russian opposition, the West has to deal with Russian fears of Western expansion by working out a new security arrangement for Europe. The West might place greater emphasis on engaging Russia constructively on a wide range of world issues. The West should also seek to involve Russia further in the Western network of organizations and agreements.