North East History Volume 50

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of the Ati-Apartheid Nlwemt 10 Police Shoot Demonstrators Dead As They Say 'Kissi, Go Home' 1I Ote Dm ,Ve Right) Entrelpages

ANTI-APARTHEID NEW ANTI-APARTHEID NEW TI " newuinpa" of the Ati-Apartheid Nlwemt 10 Police shoot demonstrators dead as they say 'Kissi, Go Home' 1i ote dm ,ve right) entrelpages. Kissinger buys time for whites campa ui moveme . La South wl .s i EC wil 'a nion recognise Transkei AT a meeting in September that what the Foreig Ministers of the carrythe nine EEC countries announced hole labo r that they wbuld not extend rebognition to the Transkei ramm Bantustan when Suth Africa rgrants it "independence on iOctober 26. KADER ASMAL, Vice Chairman of ,tment the Irish Anti-Apartheid has adopted Movement, explains the back0s5is for a ground to the decision, page 8 stment in )support SWAPO rejects SA i move on Namibia 11 1r. ai -iusive nerview witn AA NEWS, PETER KATJAVIViSWAPO' s Western European representative, sets out the liberation movement's case, page 9. Smith dismisses death appeals SO far this year, at least 37 Zimbabweans have had their appeals against death senfenee 2 . ACTION-NATIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL Britain Haringey HARINGEY Anti-Apartheid Group has held two suCjcessful house meetings and discussion groups on the Soweto crisis and after, and is planning for a major public meeting in October. Solly Smith and Ronnie Kasrils addressed groups in Crouch End andMuswell Hill on the implications of the current wave of strikes and protests in South Africa and the role of the African National Congress. On October 21 the Group is arranging a follow up to the Labour Party Conference in the form of a public meeting at which the main speaker will be Hornsey Labour Party's recently adopted Parliamen tary candidate, Ted Knight SACTU THE trade union and labour movewent must give overwhelming support to the Labour Party NEC call for a freeze on investment, mandatory economic sanctions and the halting of sales of any equipmant which enhances South Africa's military capacity. -

Bishop Press, Press, January May 30Th, 9Th, 2010.2009 Page 1 BURNS NIGHT EVENT TRAIN STATION SET for Bishop Auckland Town Hall Band

Issue No. 21 Holdforth Interiors Holdforth Crest, B.A. Tel: 01388 664777 Fax: 01388 665982 Soft Furnishings, Your local Curtains, Alterations Community Newspaper (both clothing & soft furnishings) Bishop Auckland, Saturday, January 9th, 2010. Telephone/Fax: 01388 775896 www.bishoppress.com Free Estimates Email: [email protected] - Duty journalist 0790 999 2731 No job too small Published at 3-4 First Floor Offices, Shildon Town Council, Civic Hall Square, Shildon, DL4 1AH. Competitive Rates PUBLIC CONSULTATION TO BE FREE LIFE HELD ON BRIDGE CLOSURE SKILLS COURSE A week-long People in Bishop Auckland part of the session, which will public exhibition are being offered the chance to involve a DIY lesson, where will provide join in free basic skills classes experts from Gentoo will show information to help them get the most out participants how to build flat- on an essential of life. pack furniture. scheme to repair Anyone can sign up for the Course co-ordinator, Damian a busy road half-day courses and go home Pearson, said, “We have had a bridge in Bishop with a piece of furniture they really positive response from Auckland. built themselves. the people who have done our Cockton Hill The courses have been held course so far. Railway Bridge regularly for the past year by “It is aimed at anyone in the will be closed to housing management company area and participants get to vehicles for up to Dale & Valley Homes and have keep what they build.” five weeks while proved popular with those who The next course will take Durham County have signed up. -

Escomb Saxon Church

Escomb Saxon Church The church was built around 675 AD with stone probably from the Roman Fort at Binchester. It was originally thought that the church was an offshoot of one of the local monasteries for example Whitby or Hartlepool, but this is only one of several possibilities as there are no known written records until 990 AD. Escomb is situated two miles west of Bishop Auckland in the Wear Valley. The church is one of five parishes grouped with Etherley, Hamsterley, Witton Park and Witton-le-Wear. Our church is on the national register of the Small Pilgrim Places Network. These places are small, spiritual oases, offering an atmosphere that encourages stillness, prayer and reflection for people of all faiths or none. Guides available by arrangement if required. Please contact us or visit our website for details of services. When is it on? Time of day Morning Afternoon Evening Session Day time and evening. information Who to contact Contact name Elisheva Mechanic Contact Vicar position Telephone 01388 768 898 E-mail [email protected] Website escombsaxonchurch.co.uk Where to go Name Escomb Church Address Escomb Green Escomb County Durham Postcode DL14 7SY Local Offer Local Offer Interior not accessible by wheelchair. description Disclaimer Durham County Council's Families Information Service does not promote nor endorse the services advertised on this website. Anyone seeking to use/access such services does so at their own risk and may make all appropriate enquiries about fitness for purpose and suitability to meet their needs. Call the Families Information Service: 03000 269 995 or email: [email protected] Disclaimer: Durham County Council's Families Information Service encourages and promotes the use of plain English. -

Sajal Philatelics Cover Auctions Sale No. 261 Thu 16 Aug 2007 1 Lot No

Lot No. Estimate 1924 BRITISH EMPIRE EXHIBITION 1 H.R.Harmer Display FDC with Empire Exhibition Wembley Park slogan. Minor faults, average condition. Cat £350. AT (see photo) £240 2 Plain FDC with Empire Exhibition Wembley Park slogan. Neatly slit open, tiny rust spot at bottom & ink smudge from postmark at bottom of 1d stamp, otherwise very fine fresh cover. Cat £300. AP (see photo) £220 1929 UNIVERSAL POSTAL UNION CONGRESS 3 Plain FDC with T.P.O. CDS. Relevant & rare. Slight ageing in places. UA (see photo) £160 1935 SILVER JUBILEE 4 1d value only on reverse of Silver Jubilee picture postcard with Eltham M/C. AW £80 5 Forgery of Westminster Stamp Co. illustrated FDC with London SW1 CDS. (Cat £550 as genuine). AP (see photo) £30 1937 CORONATION 6 Illustrated FDC with indistinct CDS cancelling the stamp but clear London W1 13th May M/C on reverse. Neatly slit open at top. Cat £20. AT £8 1940 CENTENARY 7 Perkins Bacon FDC with Stamp Centenary (Red Cross) Exhibition London special H/S. Cat £95. AT (see photo) £36 1946 VICTORY 8 Display FDC with Birkenhead slogan "Don't Waste Bread". Cat £75. AT £26 1960 GENERAL LETTER OFFICE 9 with Norwich CDS. Cat £200. AW (see photo) £42 1961 CEPT 10 with Torquay slogan "CEPT European Conference". Cat £15. AT £5 1961 PARLIAMENTARY CONFERENCE 11 Illustrated FDC with London SW1 slogan "Commonwealth Parliamentary Conference". Stamps badly arranged on cover. Cat £75. AT £10 1962 NATIONAL PRODUCTIVITY YEAR 12 (Phosphor) with Cannon Street EC4 CDS. Cat £90. AP (see photo) £50 1963 NATIONAL NATURE WEEK 13 (Phosphor) with Totton, Southampton CDS. -

North East History 39 2008 History Volume 39 2008

north east history north north east history volume 39 east biography and appreciation North East History 39 2008 history Volume 39 2008 Doug Malloch Don Edwards 1918-2008 1912-2005 John Toft René & Sid Chaplin Special Theme: Slavery, abolition & north east England This is the logo from our web site at:www.nelh.net. Visit it for news of activities. You will find an index of all volumes 1819: Newcastle Town Moor Reform Demonstration back to 1968. Chartism:Repression or restraint 19th Century Vaccination controversies plus oral history and reviews Volume 39 north east labour history society 2008 journal of the north east labour history society north east history north east history Volume 39 2008 ISSN 14743248 NORTHUMBERLAND © 2008 Printed by Azure Printing Units 1 F & G Pegswood Industrial Estate TYNE & Pegswood WEAR Morpeth Northumberland NE61 6HZ Tel: 01670 510271 DURHAM TEESSIDE Editorial Collective: Willie Thompson (Editor) John Charlton, John Creaby, Sandy Irvine, Lewis Mates, Marie-Thérèse Mayne, Paul Mayne, Matt Perry, Ben Sellers, Win Stokes (Reviews Editor) and Don Watson . journal of the north east labour history society www.nelh.net north east history Contents Editorial 5 Notes on Contributors 7 Acknowledgements and Permissions 8 Articles and Essays 9 Special Theme – Slavery, Abolition and North East England Introduction John Charlton 9 Black People and the North East Sean Creighton 11 America, Slavery and North East Quakers Patricia Hix 25 The Republic of Letters Peter Livsey 45 A Northumbrian Family in Jamaica - The Hendersons of Felton Valerie Glass 54 Sunderland and Abolition Tamsin Lilley 67 Articles 1819:Waterloo, Peterloo and Newcastle Town Moor John Charlton 79 Chartism – Repression of Restraint? Ben Nixon 109 Smallpox Vaccination Controversy Candice Brockwell 121 The Society’s Fortieth Anniversary Stuart Howard 137 People's Theatre: People's Education Keith Armstrong 144 2 north east history Recollections John Toft interview with John Creaby 153 Douglas Malloch interview with John Charlton 179 Educating René pt. -

Drjonespodiatryleaflet.Pdf

DARLINGTON NHS Foundation Trust Hundens Rehabilitation Centre Building A Hundens Willington Health Centre DERWENTSIDE EASINGTON Chapel Street, Willington DL15 0EQ Service Lane Darlington DL1 1JE Shotley Bridge Community Hospital Murton Clinic delivered by County Durham & Darlington NHS Service delivered by County Durham & Consett DH8 0NB 21 Woods Terrace, Murton SR7 9AG Foundation Trust. Darlington NHS Foundation Trust. Service delivered by County Durham & Service by NHS City Hospitals Sunderland Darlington NHS Foundation Trust CDDFT provide assessment and ongoing care at CDDFT provide assessment and ongoing care Peterlee Community Hospital O’Neill Drive, the clinics indicated above, they also provide at the clinics indicated above, they also Stanley Primary Care Centre Clifford Road, Peterlee SR8 5UQ Service by North Tees & following an initial assessment clinics at the provide following an initial assessment clinics Stanley DH9 0AB Service delivered by County Hartlepool NHS Foundation Trust following venues:- at the following venues:- Durham & Darlington NHS Foundation Trust. Cockfield GP Surgery Peterlee Health Centre Gainford GP Surgery Flemming Place, Peterlee SR8 1AD Evenwood GP Surgery CDDFT provide assessment and ongoing care at Whinfield Medical Practice Whinbush Way, Service by Minor Ops Limited Middleton-in-Teasdale GP Surgery the clinics indicated above, they also provide Darlington DL1 3RT Service by Minor Ops Limited following an initial assessment clinics at the Seaham Primary Care Centre following venues:- DURHAM DALES -

Northumberland Square Conservation Area Character Appraisal November 2020

NORTHUMBERLAND SQUARE CONSERVATION AREA CHARACTER APPRAISAL NOVEMBER 2020 Northumberland Square Conservation Area Character Appraisal Contents Spatial Analysis ............................................................................ 18 Introduction ..................................................................................... 5 Development Pattern ................................................................ 18 Conservation Areas ..................................................................... 5 Layout, Grain and Density ......................................................... 20 Planning Policy Context ............................................................... 5 Views within the Area ................................................................ 20 This Character Appraisal ............................................................. 6 Character Analysis ....................................................................... 23 Location and Setting ....................................................................... 7 Character Zones ....................................................................... 23 Location ....................................................................................... 7 Use and Hierarchy of Buildings ................................................. 24 Boundary ..................................................................................... 7 Architectural Qualities ............................................................... 25 Geology ...................................................................................... -

Was There an Armenian Genocide?

WAS THERE AN ARMENIAN GENOCIDE? GEOFFREY ROBERTSON QC’S OPINION WITH REFERENCE TO FOREIGN & COMMONWEALTH OFFICE DOCUMENTS WHICH SHOW HOW BRITISH MINISTERS, PARLIAMENT AND PEOPLE HAVE BEEN MISLED 9 OCTOBER 2009 “HMG is open to criticism in terms of the ethical dimension. But given the importance of our relations (political, strategic and commercial) with Turkey ... the current line is the only feasible option.” Policy Memorandum, Foreign & Commonwealth Office to Minister 12 April 1999 GRQCopCover9_wb.indd 1 20/10/2009 11:53 Was there an Armenian Genocide? Geoffrey Robertson QC’s Opinion 9 October 2009 NOTE ON THE AUTHOR Geoffrey Robertson QC is founder and Head of Doughty Street Chambers. He has appeared in many countries as counsel in leading cases in constitutional, criminal and international law, and served as first President of the UN War Crimes Court in Sierra Leone, where he authored landmark decisions on the limits of amnesties, the illegality of recruiting child soldiers and other critical issues in the development of international criminal law. He sits as a Recorder and is a Master of Middle Temple and a visiting professor in human rights law at Queen Mary College. In 2008, he was appointed by the Secretary General as one of three distinguished jurist members of the UN Justice Council. His books include Crimes Against Humanity: The Struggle for Global Justice; The Justice Game (Memoir) and The Tyrannicide Brief, an award-winning study of the trial of Charles I. GRQCopCover9_wb.indd 2 20/10/2009 11:53 Was there an Armenian Genocide? Geoffrey Robertson QC’s Opinion 9 October 2009 PREFACE In recent years, governments of the United Kingdom have refused to accept that the deportations and massacres of Armenians in Turkey in 1915 -16 amounted to genocide. -

“Run with the Fox and Hunt with the Hounds”: Managerial Trade Unionism and the British Association of Colliery Management, 1947-1994

“Run with the fox and hunt with the hounds”: managerial trade unionism and the British Association of Colliery Management, 1947-1994 Abstract This article examines the evolution of managerial trade-unionism in the British coal industry, specifically focusing on the development of the British Association of Colliery Management (BACM) from 1947 until 1994. It explores the organization’s identity from its formation as a conservative staff association to its emergence as a distinct trade union, focusing on key issues: industrial action and strike cover; affiliation to the Trades Union Congress (TUC); colliery closures; and the privatization of the coal industry. It examines BACM’s relationship with the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) and the National Association of Colliery Overmen, Deputies and Shotfirers (NACODS), the National Coal Board (NCB) and subsequently the British Coal Corporation (BCC). This is explored within the wider context of the growth of managerial trade unions in post-war Britain and managerial identity in nationalized industries. Keywords: Managerial unionism; white-collar trade unions; public ownership; coal industry The British Association of Colliery Management was a very British institution in that it seemed to have the freedom both to run with the fox and hunt with the hounds … Although it never really joined in the dispute [1984-5 miners’ strike] when it came, it took some getting used to a situation in which people who clearly laid full claim to being representatives of “management” could, and did, through their union, criticize that management.1 Former NCB chairman Ian MacGregor’s vituperative attack on BACM reflected the breakdown between the two parties and their distinct 1 outlooks on the future of the industry in the 1980s. -

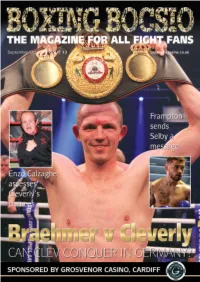

Bocsio Issue 13 Lr

ISSUE 13 20 8 BOCSIO MAGAZINE: MAGAZINE EDITOR Sean Davies t: 07989 790471 e: [email protected] DESIGN Mel Bastier Defni Design Ltd t: 01656 881007 e: [email protected] ADVERTISING 24 Rachel Bowes t: 07593 903265 e: [email protected] PRINT Stephens&George t: 01685 388888 WEBSITE www.bocsiomagazine.co.uk Boxing Bocsio is published six times a year and distributed in 22 6 south Wales and the west of England DISCLAIMER Nothing in this magazine may be produced in whole or in part Contents without the written permission of the publishers. Photographs and any other material submitted for 4 Enzo Calzaghe 22 Joe Cordina 34 Johnny Basham publication are sent at the owner’s risk and, while every care and effort 6 Nathan Cleverly 23 Enzo Maccarinelli 35 Ike Williams v is taken, neither Bocsio magazine 8 Liam Williams 24 Gavin Rees Ronnie James nor its agents accept any liability for loss or damage. Although 10 Brook v Golovkin 26 Guillermo 36 Fight Bocsio magazine has endeavoured 12 Alvarez v Smith Rigondeaux schedule to ensure that all information in the magazine is correct at the time 13 Crolla v Linares 28 Alex Hughes 40 Rankings of printing, prices and details may 15 Chris Sanigar 29 Jay Harris 41 Alway & be subject to change. The editor reserves the right to shorten or 16 Carl Frampton 30 Dale Evans Ringland ABC modify any letter or material submitted for publication. The and Lee Selby 31 Women’s boxing 42 Gina Hopkins views expressed within the 18 Oscar Valdez 32 Jack Scarrott 45 Jack Marshman magazine do not necessarily reflect those of the publishers. -

ISC Annual Report 2003-2004

Intelligence and Security Committee Annual Report 2003–2004 Chairman: The Rt. Hon. Ann Taylor, MP Intelligence Services Act 1994 Chapter 13 Cm 6240 £10.50 Intelligence and Security Committee Annual Report 2003–2004 Chairman: The Rt. Hon. Ann Taylor, MP Intelligence Services Act 1994 Chapter 13 Presented to Parliament by the Prime Minister by Command of Her Majesty JUNE 2004 Cm 6240 £10.50 ©Crown Copyright 2004 The text in this document (excluding the Royal Arms and departmental logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and the title of the document specified. Any enquiries relating to the copyright in this document should be addressed to The Licensing Division, HMSO, St Clements House, 2–16 Colegate, Norwich NR3 1BQ. Fax: 01603 723000 or e-mail: [email protected] From the Chairman: The Rt. Hon. Ann Taylor, MP INTELLIGENCE AND SECURITY COMMITTEE 70 Whitehall London SW1 2AS 26 May 2004 Rt. Hon. Tony Blair, MP Prime Minister 10 Downing Street London SW1A 2AA In September 2003 the Committee produced a unanimous Report following our inquiry into Iraqi Weapons of Mass Destruction – Intelligence and Assessments. I now enclose the Intelligence and Security Committee’s Annual Report for 2003–04. This Report records how we have examined the expenditure, administration and policies of the three intelligence and security Agencies. We also report to you on a number of other Agency related matters and the wider intelligence community. -

Popular Political Oratory and Itinerant Lecturing in Yorkshire and the North East in the Age of Chartism, 1837-60 Janette Lisa M

Popular political oratory and itinerant lecturing in Yorkshire and the North East in the age of Chartism, 1837-60 Janette Lisa Martin This thesis is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of York Department of History January 2010 ABSTRACT Itinerant lecturers declaiming upon free trade, Chartism, temperance, or anti- slavery could be heard in market places and halls across the country during the years 1837- 60. The power of the spoken word was such that all major pressure groups employed lecturers and sent them on extensive tours. Print historians tend to overplay the importance of newspapers and tracts in disseminating political ideas and forming public opinion. This thesis demonstrates the importance of older, traditional forms of communication. Inert printed pages were no match for charismatic oratory. Combining personal magnetism, drama and immediacy, the itinerant lecturer was the most effective medium through which to reach those with limited access to books, newspapers or national political culture. Orators crucially united their dispersed audiences in national struggles for reform, fomenting discussion and coalescing political opinion, while railways, the telegraph and expanding press reportage allowed speakers and their arguments to circulate rapidly. Understanding of political oratory and public meetings has been skewed by over- emphasis upon the hustings and high-profile politicians. This has generated two misconceptions: that political meetings were generally rowdy and that a golden age of political oratory was secured only through Gladstone’s legendary stumping tours. However, this thesis argues that, far from being disorderly, public meetings were carefully regulated and controlled offering disenfranchised males a genuine democratic space for political discussion.