Perceptions of Meaningfulness Among High School Instrumental

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newly Cataloged Items in the Music Library August - December 2017

Newly Cataloged Items in the Music Library August - December 2017 Call Number Author Title Publisher Enum Publication Date MUSIC. MCD3.C63 B37 v.1 Vivaldi, Antonio, 1678- Vivaldi : Venetian splendour. International Masters 2006 2006 1741. Pub., MUSIC. MCD3.C63 B37 v.2 Bach, Johann Sebastian, Bach : Baroque masterpieces. International Masters 2005 2005 1685-1750. Pub., MUSIC. MCD3.C63 B37 v.3 Bach, Johann Sebastian, Bach : master musician. International Masters 2007 2007 1685-1750. Pub., MUSIC. MCD3.C63 B37 v.5 Handel, George Frideric, Handel : from opera to oratorio. International Masters 2006 2006 1685-1759. Pub., MUSIC. MCD3.C63 C63 v.1 Haydn, Joseph, 1732- Haydn : musical craftsman. International Masters 2006 2006 1809. Pub., MUSIC. MCD3.C63 C63 v.2 Haydn, Joseph, 1732- Haydn : master of music. International Masters 2006 2006 1809. Pub., MUSIC. MCD3.C63 C63 v.3 Mozart, Wolfgang Mozart : musical masterpieces. International Masters 2005 2005 Amadeus, 1756-1791. Pub., MUSIC. MCD3.C63 C63 v.4 Mozart, Wolfgang Mozart : classic melodies. International Masters 2005 2005 Amadeus, 1756-1791. Pub., MUSIC. MCD3.C63 C63 v.5 Mozart, Wolfgang Mozart : magic of music. International Masters 2007 2007 Amadeus, 1756-1791. Pub., MUSIC. MCD3.C63 E17 .1 Beethoven, Ludwig van, Beethoven : the spirit of freedom. International Masters 2005 2005 1770-1827. Pub., MUSIC. MCD3.C63 E17 Rossini, Gioacchino, Rossini : opera and overtures. International Masters 2006 v.10 2006 1792-1868. Pub., MUSIC. MCD3.C63 E17 Schumann, Robert, 1810- Schumann : poetry and romance. International Masters 2006 v.11 2006 1856. Pub., MUSIC. MCD3.C63 E17 Mendelssohn-Bartholdy, Mendelssohn : dreams and fantasies. International Masters 2005 v.12 2005 Felix, 1809-1847. -

![Downloads.Html [Accessed November 29, 2011]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4308/downloads-html-accessed-november-29-2011-1214308.webp)

Downloads.Html [Accessed November 29, 2011]

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 A Performer's Guide to Dr. Thomas Jefferson Anderson's Sunstar for Solo B-Flat Trumpet and Two Cassette Recorders Kenneth C. Trimmins Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC A PERFORMER’S GUIDE TO DR. THOMAS JEFFERSON ANDERSON’S SUNSTAR FOR SOLO B-FLAT TRUMPET AND TWO CASSETTE RECORDERS By KENNETH C. TRIMMINS A treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2012 Kenneth C. Trimmins defended this treatise on June 27, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Christopher R. Moore Professor Directing Treatise Richard Clary University Representative Paul Ebbers Committee Member Patrick Meighan Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the treatise has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii I believe in the old saying about a village raising a child. I would like to dedicate this document to the “village” that raised and educated me; my entire family, former teachers and friends who have been so supportive of me during my life of learning. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I want to thank God for giving me the strength and presence of mind to accomplish this wonderful achievement. The completion of this treatise would not have been possible without the encouragement, assistance and support of many people. First, to the members of my committee: Christopher Moore, Richard Clary, Patrick Meighan, and Paul Ebbers. -

Canada 14Usic

TTItr CAI{ADIAAT MUSIC TtrACHER LE PROFESSET_IR DE MUSTQUE CANADTEN oF Muslc lE4c,,eaa. -{f€o€FAnoN r"*2.,fo* c-ffi'r,A % 'W' o CFMTA tt^n't*f*ff#**.*d FCAPM CANADA 14USIC otfft'" t*""t""'ru" -rr$teoeRerto* "\ "".- cFffisl-A iwr 7 CONTTNIS n-*"^"F"#HM.,".."d h|EEK* Greetings from CFMT4....................... 3 Pyovincial Co-ordinators ............ ..........4 Canada Music WeekrM Supplies ............5 LA SEMAINE DE LA MUSIOUE CANADIENNE Diamond Jubilee CoIIection .................6 From the Provinces ..............................8 Editing Your Composition,................13 M)'sten' Music ....,.............14 Lessons With Yiolet fucher................I5 Inten'ierv u'ith Nlartin Beaver.............16 Classical trlusic Comes to lvlanitoulin ............ ........21 The Forsvths...,.,......... ......23 Music and Creativin' ............ ..............27 Music Writing Competition ...............29 1999 Provincial Winners ............ ........29 Music Writing Competition Regulations...............30 Music Writing Entry Form........ .........32 Music Writing Competition Winners .......33 Reviervs.... ........37 Music Qui2......... ..............39 - I - Executive Directory ..........40 NOVEMBEP 19 26 ' 2OAO P 26 NOVEMBPE Advertising Rate Card. ......42 The Prcven Theory Series It's the proven series to help your students learn, understand, enjoy and excel on RCM exams. Written by one of Canada's leading theorists and the former head of exams for the Royal Conservatory. The Lawless Theory Series Tnk,tl ,i Getting off to the right start... This -

JOURNAL of the AMERICAN THEATRE ORGAN SOCIETY Orbil ID™E Eclronic 1Ynrhe1izer P,UJ ~ -~Oh Xe01pinel Orgon Equoj

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN THEATRE ORGAN SOCIETY Orbil ID™e eclronic 1ynrhe1izer P,UJ ~ -~oh_xe01pinel orgon equoJ... rhenewe;I woy lo mo <.emu1ic fromWur irzec Now with the Orbit III electronic synthesizer from slowly, just as the theatre organist did by opening and Wurlitzer you can create new synthesized sounds in closing the chamber louvers. stantly ... in performance. And with the built-in Orbit III synthesizer, this This new Wurlitzer instrument is also a theatre organ, instrument can play exciting combinations of synthe with a sectionalized vibrato/tremolo, toy counter, in sized, new sounds, along with traditional organ music. A dependent tibias on each keyboard and the penetrating built-in cassette player/recorder lets you play along with kinura voice that all combine to recreate the sounds of pre-recorded tapes for even more dimensions in sound. the twenty-ton Mighty Wurlitzers of silent screen days. But you've got to play the Orbit III to believe it. And it's a cathedral/classical organ, too, with its own in Stop in at your Wurlitzer dealer and see the Wurlitzer dividually voiced diapason, reed, string and flute voices. 4037 and 4373. Play the eerie, switched-on sounds New linear accent controls permit you to increase or of synthesized music. Ask for your free Orbit III decrease the volume of selected sections suddenly, or demonstration record. Or write: Dep t: 1072 WURLilzER ® The Wurlitzer Company, DeKalb, Illinois 60115. ha.4'1he ,vay cover- photo ... Genii's console, the 3/13 235 Special Wurlitzer with Brass Trumpet, was installed in the Canal Street Theatre in New York in 1927, and was moved to the Triboro The atre in Queens, New York in 1931. -

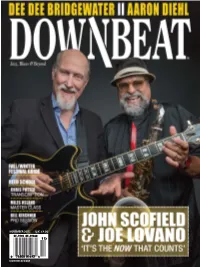

Downbeat.Com November 2015 U.K. £4.00

NOVEMBER 2015 2015 NOVEMBER U.K. £4.00 DOWNBEAT.COM DOWNBEAT JOHN SCOFIELD « DEE DEE BRIDGEWATER « AARON DIEHL « ERIK FRIEDLANDER « FALL/WINTER FESTIVAL GUIDE NOVEMBER 2015 NOVEMBER 2015 VOLUME 82 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer ĺDQHWDÎXQWRY£ Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Bookkeeper Emeritus Margaret Stevens Editorial Assistant Stephen Hall Editorial Intern Baxter Barrowcliff ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sam Horn 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; -

August 1910) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 8-1-1910 Volume 28, Number 08 (August 1910) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 28, Number 08 (August 1910)." , (1910). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/561 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CELEBRATED CONTRIBUTORS TO THE ETUDE KJiAkt U THE ETVDE AUGUST 1910 Theo. PresserCo.. Philadelphia.Pa. 501 STUDIES IN OCTAVES | THE ETUDE New ADVANCED PASSAGE-WORK Publications EIGHT MELODIOUS STUDIES IN MODERN TECHNIC Premiums and Special Offers Easy Engelmann Album By CEZA HORVATH Singers’ Repertoire Studies for the Lett Hand Op. 87, Price $ 1.25 Crade IV-V FOR THE PIANO These « are in gM of Interest to Our Readers A Collection of Sacred end Secular Alone k. MONTHLY JOURNAL FOR THE MUSICIAN, T Songs for Medium Voice Price. 50 Cents MUSIC STUDENT, AND ALL MUSIC LOVERS. Price. 50 Cents For the Pianoforte Edited by .TAMES FRANCIS COOKE Twenty-six of Mr. -

JAZZ: a Regional Exploration

JAZZ: A Regional Exploration Scott Yanow GREENWOOD PRESS JAZZ A Regional Exploration GREENWOOD GUIDES TO AMERICAN ROOTS MUSIC JAZZ A Regional Exploration Scott Yanow Norm Cohen Series Editor GREENWOOD PRESS Westport, Connecticut • London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Yanow, Scott. Jazz : a regional exploration / Scott Yanow. p. cm. – (Greenwood guides to American roots music, ISSN 1551-0271) Includes bibliographical references and index. Discography: p. ISBN 0-313-32871-4 (alk. paper) 1 . Jazz—History and criticism. I. Title. II. Series. ML3508.Y39 2005 781.65'0973—dc22 2004018158 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2005 by Scott Yanow All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2004018158 ISBN: 0-313-32871-4 ISSN: 1551-0271 First published in 2005 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48-1984). 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents Series Foreword vii Preface xi Chronology xiii Introduction xxiii 1. Sedalia and St. Louis: Ragtime 1 2. New Orleans Jazz 7 3. Chicago: Classic Jazz 15 4. New York: The Classic Jazz and Swing Eras 29 5. Kansas City Swing, the Territory Bands, and the San Francisco Revival 99 6. New York Bebop, Latin, and Cool Jazz 107 7. -

Concerts for Kids

Concerts for Kids Study Guide 2014-15 San Francisco Symphony Davies Symphony Hall study guide cover 1415_study guide 1415 9/29/14 11:41 AM Page 2 Children’s Concerts – “Play Me A Story!” Donato Cabrera, conductor January 26, 27, 28, & 30 (10:00am and 11:30am) Rossini/Overture to The Thieving Magpie (excerpt) Prokofiev/Excerpts from Peter and the Wolf Rimsky-Korsakov/Flight of the Bumblebee Respighi/The Hen Bizet/The Doll and The Ball from Children’s Games Ravel/Conversations of Beauty and the Beast from Mother Goose Prokofiev/The Procession to the Zoo from Peter and the Wolf Youth Concerts – “Music Talks!” Edwin Outwater, conductor December 3 (11:30am) December 4 & 5 (10:00am and 11:30am) Mussorgsky/The Hut on Fowl’s Legs from Pictures at an Exhibition Strauss/Till Eulenspiegel’s Merry Pranks (excerpt) Tchaikovsky/Odette and the Prince from Swan Lake Kvistad/Gending Bali for Percussion Grieg/In the Hall of the Mountain King from Peer Gynt Britten/Storm from Peter Grimes Stravinsky/Finale from The Firebird San Francisco Symphony children’s concerts are permanently endowed in honor of Mrs. Walter A. Haas. Additional support is provided by the Mimi and Peter Haas Fund, the James C. Hormel & Michael P. NguyenConcerts for Kids Endowment Fund, Tony Trousset & Erin Kelley, and Mrs. Milton Wilson, together with a gift from Mrs. Reuben W. Hills. We are also grateful to the many individual donors who help make this program possible. San Francisco Symphony music education programs receive generous support from the Hewlett Foundation Fund for Education, the William Randolph Hearst Endowment Fund, the Agnes Albert Youth Music Education Fund, the William and Gretchen Kimball Education Fund, the Sandy and Paul Otellini Education Endowment Fund, The Steinberg Family Education Endowed Fund, the Jon and Linda Gruber Education Fund, the Hurlbut-Johnson Fund, and the Howard Skinner Fund. -

The Conductor-Teacher, Conductor-Learner: an Autoethnography of the Dynamic Conducting/Teaching, Learning Process of an Advanced Level Wind Ensemble Conductor

The conductor-teacher, conductor-learner: An autoethnography of the dynamic conducting/teaching, learning process of an advanced level wind ensemble conductor By Stephen Mark King B. App Comp, B.P.A. (Mus), B. Teach (Hons) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Education (Research) Faculty of Education University of Tasmania June 2011 STATEMENT OF ORIGINALITY This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of the my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis, nor does the thesis contain any material that infringes copyright. ……………………………………… Stephen King i PERMISSION TO COPY I hereby give permission to the staff of the University Library and to staff and the students of the Faculty of Education within the University of Tasmania to copy this thesis. This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. This permission covers only single copies made for study purposes, subject to normal conditions of acknowledgement. ……………………………………… Stephen King ii STATEMENT OF ETHICAL CONDUCT The research associated with this thesis abides by the international and Australian codes on human and animal experimentation, the guidelines by the Australian Government's Office of the Gene Technology Regulator and the rulings of the Safety, Ethics and Institutional Biosafety Committees of the University. ……………………………………… Stephen King iii ABSTRACT This study aimed to examine the nature of the work of a conductor-music educator, more specifically my lived experience as a music educator, conductor and performer as I worked with a community music program in regional Tasmania, Australia. -

SMT-Based Generation of Film Scores from Lightweight Annotations

SMT-Based Generation of Film Scores From Lightweight Annotations Halley Young Department of Computer Science University of Pennsylvania Pennsylvania, PA 19104, USA [email protected] September 2020 1 Introduction The film industry turns out over $200 billion of films every year, and a sub- stantial portion of that is spent creating appealing film scores [14]. According to studies by Stuart Fischoff, himself both a film writer and scholar of me- dia psychology, music scores to films account for much of our understanding of the emotional impact of film scenes as well as characterizations of different characters, locations, and events [5]. However, there has not been substantial research on formalizing the way that film scores produce these effects. While there has been some research on producing film scores semi-automatically, these approaches are either statistical (and suffer the same problems as most deep- learning based music, such as lack of memorable material or global structure), or don't include a background theory of film composition, and thus require ex- tensive manual specification by the composer [13] [6]. This study addresses the formalization of a theory of film music, written in a decidable fragment of first- order logic. This theory allows for the generation of appropriate film music from extremely lightweight annotations. 2 Input and Output The input to the algorithm is a specification. A specification contains an arbi- trary lines, each of which contains a list of variables, a specified duration time in seconds, and optionally a description of the scene (used only for documentation and not by the algorithm). -

Kyle Dean Pruett, MD

Kyle Dean Pruett, M.D. BORN 27 August 1943 Raton, New Mexico EDUCATION 1965 B.A. in History and Music, Yale University 1967 Summer fellowship in child psychiatry/Langley Porter Neuropsychiatric Institute, San Francisco, CA 1969 M.D. Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, MA CAREER 7/1/1969-6/30/70 Combined Internship, Mt. Auburn Hospital (Harvard University), Cambridge, MA, and Boston City Hospital (Pediatrics) 7/1/1970-6/30/72 Psychiatry Residency, Tufts New England Medical Center, Boston, MA 7/1/1972-6/30/74 Child Psychiatry Fellowship, Yale Child Study Center, New Haven, CT 7/1/1974-6/30/08 Private practice of Child, Adolescent, Adult, and Family Psychiatry, New Haven and Guilford, CT 9/1/1974-8/30/76 Staff child psychiatrist, Adolescent Crisis Unit for Treatment and Evaluation, St. Raphael's Hospital, New Haven, CT 5/1/1975-8/1/75 Visiting Fellow, Hampstead Child Therapy Clinic with Anna Freud, London, England, fall 7/1/1975-6/30/79 Assistant Clinical Professor of Psychiatry, Yale Child Study Center 9/1/1978-6/30/08 Attending Physician, Yale-New Haven Hospital 7/1/1979-6/30/87 Associate Clinical Professor of Psychiatry, Yale Child Study Center; Coordinator of Training, Child Development Unit 7/1/1987-present Clinical Professor of Psychiatry, Yale Child Study Center, Yale University School of Medicine 7/1/1993-present Joint Appointment as Clinical Professor, Yale School of Nursing 1995-98 Coordinator of Education and Training, Yale Child Study Center 1999-2007 Director of Medical Studies, Yale Child Study Center 1999-2007 Director -

Sendung, Sendedatum

WDR 3 Jazz & World, 19. Mai 2018 Persönlich mit Götz Alsmann 13:04-14:45 Stand: 17.05.2018 E-Mail: [email protected] WDR JazzRadio: http://jazz.wdr.de Moderation: Götz Alsmann Redaktion: Bernd Hoffmann 22:04-24:00 Laufplan 1. Hotshoe K/T: Leith Stevens 2:38 LEITH STEVENS Bear Family 16393; LC: 05197 CD: The Wild One 2. If I Ever Find You, Baby K/T: Buddy Johnson 2:11 BUDDY JOHNSON Decca 2641; LC: 00171 Single 3. Hard Rocks In My Bed K/T: Amos Easton 2:45 BUMBLE BEE SLIM Magpie 1801; LC: 99999 LP: Everybody’s Fishing 4. Where Are You K/T: Harold Adamson/ Jimmy McHugh 4:51 BEN WEBSTER & Verve 8349; LC: 00383 OSCAR PETERSON LP: Ben Webster Meets Oscar Peterson 5. Perdido K/T: Juan Tizol/ HarryLenk/ Ervin Drake 6:13 OSCAR PETERSON MPS 15181; LC: 00979 LP: My Favorite Instrument 6. Singin’ In The Rain K/T: Nacio Brown/ Arthur Freed 2:55 TONI HARPER Verve 2001; LC: 00383 LP: Toni 7. Goody Goody K/T: Johnny Mercer/ Matty Malneck 1:58 ELLA FITZGERALD Verve 2332051; LC: 00383 LP: The Best Of Ella Fitzgerald 8. Jam Up K/T: Tommy Ridgley 2:54 TOMMY RIDGLEY Atlantic 8162; LC: 00121 LP: History of Rhythm & Blues Vol.2 9. Looped K/T: Jesse Allen 2:24 TOMMY RIDGLEY Imperial 5203; LC: 00116 Single 10. King Solomon’s Blues K/T: Jerry Leiber/ Mike Stoller 2:29 GIL BERNAL Spark 106 Single Dieses Manuskript ist ausschließlich zum persönlichen, privaten Gebrauch bestimmt. Jede weitere Vervielfältigung und Verbreitung bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des WDR.