Musical Innovation, Collaboration, and Ideological Expression in the Chilean Netlabel Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beyond Salsa Bass the Cuban Timba Revolution

BEYOND SALSA BASS THE CUBAN TIMBA REVOLUTION VOLUME 1 • FOR BEGINNERS FROM CHANGÜÍ TO SON MONTUNO KEVIN MOORE audio and video companion products: www.beyondsalsa.info cover photo: Jiovanni Cofiño’s bass – 2013 – photo by Tom Ehrlich REVISION 1.0 ©2013 BY KEVIN MOORE SANTA CRUZ, CA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED No part of this publication may be reproduced in whole or in part, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording or otherwise, without written permission of the author. ISBN‐10: 1482729369 ISBN‐13/EAN‐13: 978‐148279368 H www.beyondsalsa.info H H www.timba.com/users/7H H [email protected] 2 Table of Contents Introduction to the Beyond Salsa Bass Series...................................................................................... 11 Corresponding Bass Tumbaos for Beyond Salsa Piano .................................................................... 12 Introduction to Volume 1..................................................................................................................... 13 What is a bass tumbao? ................................................................................................................... 13 Sidebar: Tumbao Length .................................................................................................................... 1 Difficulty Levels ................................................................................................................................ 14 Fingering.......................................................................................................................................... -

Redalyc.Mambo on 2: the Birth of a New Form of Dance in New York City

Centro Journal ISSN: 1538-6279 [email protected] The City University of New York Estados Unidos Hutchinson, Sydney Mambo On 2: The Birth of a New Form of Dance in New York City Centro Journal, vol. XVI, núm. 2, fall, 2004, pp. 108-137 The City University of New York New York, Estados Unidos Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=37716209 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Hutchinson(v10).qxd 3/1/05 7:27 AM Page 108 CENTRO Journal Volume7 xv1 Number 2 fall 2004 Mambo On 2: The Birth of a New Form of Dance in New York City SYDNEY HUTCHINSON ABSTRACT As Nuyorican musicians were laboring to develop the unique sounds of New York mambo and salsa, Nuyorican dancers were working just as hard to create a new form of dance. This dance, now known as “on 2” mambo, or salsa, for its relationship to the clave, is the first uniquely North American form of vernacular Latino dance on the East Coast. This paper traces the New York mambo’s develop- ment from its beginnings at the Palladium Ballroom through the salsa and hustle years and up to the present time. The current period is characterized by increasing growth, commercialization, codification, and a blending with other modern, urban dance genres such as hip-hop. [Key words: salsa, mambo, hustle, New York, Palladium, music, dance] [ 109 ] Hutchinson(v10).qxd 3/1/05 7:27 AM Page 110 While stepping on count one, two, or three may seem at first glance to be an unimportant detail, to New York dancers it makes a world of difference. -

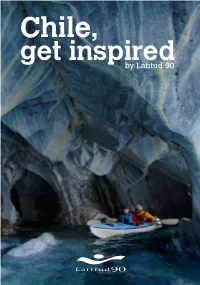

Latitud 90 Get Inspired.Pdf

Dear reader, To Latitud 90, travelling is a learning experience that transforms people; it is because of this that we developed this information guide about inspiring Chile, to give you the chance to encounter the places, people and traditions in most encompassing and comfortable way, while always maintaining care for the environment. Chile offers a lot do and this catalogue serves as a guide to inform you about exciting, adventurous, unique, cultural and entertaining activities to do around this beautiful country, to show the most diverse and unique Chile, its contrasts, the fascinating and it’s remoteness. Due to the fact that Chile is a country known for its long coastline of approximately 4300 km, there are some extremely varying climates, landscapes, cultures and natures to explore in the country and very different geographical parts of the country; North, Center, South, Patagonia and Islands. Furthermore, there is also Wine Routes all around the country, plus a small chapter about Chilean festivities. Moreover, you will find the most important general information about Chile, and tips for travellers to make your visit Please enjoy reading further and get inspired with this beautiful country… The Great North The far north of Chile shares the border with Peru and Bolivia, and it’s known for being the driest desert in the world. Covering an area of 181.300 square kilometers, the Atacama Desert enclose to the East by the main chain of the Andes Mountain, while to the west lies a secondary mountain range called Cordillera de la Costa, this is a natural wall between the central part of the continent and the Pacific Ocean; large Volcanoes dominate the landscape some of them have been inactive since many years while some still present volcanic activity. -

Program Notes

studying clarinet with her father, Nick Cionitti, followed by lessons with Valentine Anzalone and Michael Webster. She received her B.M. degree from the Crane School of Music at SUNY Potsdam, studying with Alan Woy. Her M.M. and D.M.A. degrees are from Michigan State University, where she studied with Elsa Ludewig-Verdehr. Maila Gutierrez Springfield is an instructor at Valdosta State University and a member of the Maharlika Trio, a group dedicated to commissioning and performing new works for saxophone, trombone and piano. She can be heard on saxophonist Joren Cain’s CD Voices of Dissent and on clarinetist Linda Cionitti’s CD Jag & Jersey. MusicWeb International selected Jag & Jersey as the recording of the month for February 2010 and noted that Maila “is superb in the taxing piano part with its striding bass lines and disjointed rhythms”. For Voices of Dissent, the American Record Guide describes Maila as “an excellent pianist, exhibiting solid technique and fine touch and pedal work." Twice- honored with the Excellence in Accompanying Award at Eastman School of Music, Maila has been staff accompanist for the Georgia Governor’s Honors Program, Georgia Southern University, the Buffet Crampon Summer Clarinet Academy and the Interlochen Arts Camp where she had the privilege of working with cellist Yo-Yo Ma. She has collaborated with members of major symphony orchestras, including those in Philadelphia, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Los Angeles and Jacksonville. She was awarded a Bachelor of Music degree from Syracuse University, and a Master of Music degree from the Eastman School of Music. SELECTED RELATED LIBRARY RESOURCES 780.92 A1N532, 1984 The New Grove modern masters : Bartók, Stravinsky, Hindemith 788.620712 S932s 1970 The study of the clarinet / by William H. -

Listado De Generos Autorizados.Xls

POR SUBGENERO LISTADO DE GENEROS AUTORIZADOS ACTUALIZADO AL 10 / 10 / 2006 SUBGENERO CODIGO GENERO AFRO 500 INTERNACIONAL AGOGO 594 INTERNACIONAL AIRES ESPAÑOLES 501 INTERNACIONAL ALBORADA 502 INTERNACIONAL ALEGRO VIVACE 455 SINFONICO Y CAMARA ANATEADA 627 FOLKLORE ANDANTE 400 SINFONICO Y CAMARA ARIA 401 SINFONICO Y CAMARA AUQUI AUQUI 633 FOLKLORE BAGUALA 300 FOLKLORE BAILECITO 301 FOLKLORE BAILE 402 INTERNACIONAL BAILES 302 FOLKLORE BAION 503 INTERNACIONAL BALADA 100 MELODICO BALLET 403 SINFONICO Y CAMARA BAMBUCO 595 INTERNACIONAL BARCAROLA 504 INTERNACIONAL BATUCADA 505 INTERNACIONAL BEAT 101 MELODICO BEGUINE 102 MELODICO BERCEUSE 404 SINFONICO Y CAMARA BLUES 103 MELODICO BOCETO 405 SINFONICO Y CAMARA BOGALOO 105 MELODICO BOLERO 104 MELODICO BOMBA 506 INTERNACIONAL BOOGIE BOOGIE 106 MELODICO BOSSA NOVA 507 INTERNACIONAL BOTECITO 508 INTERNACIONAL BULERIAS 509 INTERNACIONAL CACHACA 615 INTERNACIONAL CACHARPAYA 302 FOLKLORE CAJITA DE MUSICA 406 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CALIPSO 107 MELODICO CAMPERA 303 FOLKLORE CAN CAN 510 INTERNACIONAL CANCION 108 MELODICO CANCION DE CUNA 453 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CANCION FOLKLORICA 358 FOLKLORE Página 1 POR SUBGENERO LISTADO DE GENEROS AUTORIZADOS ACTUALIZADO AL 10 / 10 / 2006 SUBGENERO CODIGO GENERO CANCION INDIA 643 FOLKLORE CANCION INFANTIL 407 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CANCION MAPUCHE 642 FOLKLORE CANDOMBE 1 POPULAR CANON 408 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CANTATA 409 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CANTE JONDO 511 INTERNACIONAL CANZONETTA 109 MELODICO CAPRICCIO 410 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CARAMBA 304 FOLKLORE CARNAVAL 348 FOLKLORE CARNAVALITO -

Dossierdelio2019-2020-EN.Pdf

La Delio Valdez is an orchestra born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, in 2009. It is a group of musicians who has developed an original proposal rooted in cumbia, a genre that has spread throughout Latin America like a common musical language. La Delio Valdez (from now on: LDV) takes up the continent’s rich orchestral tra- dition. It mirrors certain aspects of Argentina’s national tango orchestras, namely their cooperative organization, their excellence and their theatricality on stage. It also emulates the great Caribbean orchestras of the past in that it counts dance and potent and overwhelming sound among the essential features of its style. LDV reappropria- tes those languages in its own way and renders them in a more modern format, where the electric and the acoustic blend. LDV’s music has a varied quality which fusions features from other genres: the Andean tradition, salsa, rock, jazz and reggae, to yield a style that is both traditional and modern. An international and contemporary sound which reflects the region’s mestizo identities. LDV’s repertoire includes both original works by the orchestra and arrangements of pieces belonging to the Latin American songbook. To these ends, the orchestra counts on a rhythm section made up of six musicians: Pedro Rodriguez in vocals, timpani with bass drums, and tambora; Sebastían Ague- ro in conga drums; Tomás Arístide in guiro and/or maracas; Marcos “Pollo” Díaz in bongoes and conical drums (“tambor alegre” in Spanish); Manuel Cibrian in vo- cals and guitar, and León Podolsky in electric bass. Plus, a section made up of seven winds: Agustina Massara, Pablo Broide in alto and tenor saxophones; Santiago Mol- dovan in the clarinet; Milton Rodriguez and Damian Chavarria in trombones; Pa- blo Vazquez Reyna and Agustin Zuanigh in trumpets. -

Music Industry Report 2020 Includes the Work of Talented Student Interns Who Went Through a Competitive Selection Process to Become a Part of the Research Team

2O2O THE RESEARCH TEAM This study is a product of the collaboration and vision of multiple people. Led by researchers from the Nashville Area Chamber of Commerce and Exploration Group: Joanna McCall Coordinator of Applied Research, Nashville Area Chamber of Commerce Barrett Smith Coordinator of Applied Research, Nashville Area Chamber of Commerce Jacob Wunderlich Director, Business Development and Applied Research, Exploration Group The Music Industry Report 2020 includes the work of talented student interns who went through a competitive selection process to become a part of the research team: Alexander Baynum Shruthi Kumar Belmont University DePaul University Kate Cosentino Isabel Smith Belmont University Elon University Patrick Croke University of Virginia In addition, Aaron Davis of Exploration Group and Rupa DeLoach of the Nashville Area Chamber of Commerce contributed invaluable input and analysis. Cluster Analysis and Economic Impact Analysis were conducted by Alexander Baynum and Rupa DeLoach. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 5 - 6 Letter of Intent Aaron Davis, Exploration Group and Rupa DeLoach, The Research Center 7 - 23 Executive Summary 25 - 27 Introduction 29 - 34 How the Music Industry Works Creator’s Side Listener’s Side 36 - 78 Facets of the Music Industry Today Traditional Small Business Models, Startups, Venture Capitalism Software, Technology and New Media Collective Management Organizations Songwriters, Recording Artists, Music Publishers and Record Labels Brick and Mortar Retail Storefronts Digital Streaming Platforms Non-interactive -

Transnational Trajectories of Colombian Cumbia

SPRING 2020 TRANSNATIONAL TRAJECTORIES OF COLOMBIAN CUMBIA Transnational Trajectories of Colombian Cumbia Dr. Lea Ramsdell* Abstract: During 19th and 20th century Latin America, mestizaje, or cultural mixing, prevailed as the source of national identity. Through language, dance, and music, indigenous populations and ethnic groups distinguished themselves from European colonizers. Columbian cumbia, a Latin American folk genre of music and dance, was one such form of cultural expression. Finding its roots in Afro-descendant communities in the 19th century, cumbia’s use of indigenous instruments and catchy rhythm set it apart from other genres. Each village added their own spin to the genre, leaving a wake of individualized ballads, untouched by the music industry. However, cumbia’s influence isn’t isolated to South America. It eventually sauntered into Mexico, crossed the Rio Grande, and soon became a staple in dance halls across the United States. Today, mobile cumbia DJ’s, known as sonideros, broadcast over the internet and radio. By playing cumbia from across the region and sending well-wishes into the microphone, sonideros act as bridges between immigrants and their native communities. Colombian cumbia thus connected and defined a diverse array of national identities as it traveled across the Western hemisphere. Keywords: Latin America, dance, folk, music, cultural exchange, Colombia What interests me as a Latin Americanist are the grassroots modes of expression in marginalized communities that have been simultaneously disdained and embraced by dominant sectors in their quest for a unique national identity. In Latin America, this tension has played out time and again throughout history, beginning with the newly independent republics in the 19th century that sought to carve a national identity for themselves that would set them apart – though not too far apart – from the European colonizers. -

Donn Borcherdt Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt0t1nc989 No online items Finding Aid for the Donn Borcherdt Collection 1960-1964 Processed by . Ethnomusicology Archive UCLA 1630 Schoenberg Music Building Box 951657 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1657 Phone: (310) 825-1695 Fax: (310) 206-4738 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.ethnomusic.ucla.edu/Archive/ ©2007 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Donn 1966.01 1 Borcherdt Collection 1960-1964 Descriptive Summary Title: Donn Borcherdt Collection, Date (inclusive): 1960-1964 Collection number: 1966.01 Creator: Borcherdt, Donn Extent: 7 boxes Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Ethnomusicology Archive Los Angeles, California 90095-1490 Abstract: This collection consists of sound recordings and field notes. Language of Material: Collection materials in English, Spanish Access Archive materials may be accessed in the Archive. As many of our collections are stored off-site at SRLF, we recommend you contact the Archive in advance to check on the availability of the materials. Publication Rights Archive materials do not circulate and may not be duplicated or published without written permission from the copyright holders, collectors, and/or performers. For more information contact the Archive Librarians: [email protected]. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Donn Borcherdt Collection, 1966.01, Ethnomusicology Archive, University of California, Los Angeles. Biography Donn Borcherdt was born in Montrose, California. Borcherdt was a composer and pianist. After he received his BA from UCLA in composition and conducting, he began his graduate studies in ethnomusicology in 1956, focusing first on Armenian folk music and, later, on the music of Mexico. -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

UNIVERSIDAD VERACRUZANA Ecos De La Bamba. Una Historia

UNIVERSIDAD VERACRUZANA INSTITUTO DE INVESTIGACIONES HISTÓRICO -SOCIALES DOCTORADO EN HISTORIA Y ESTUDIOS REGIONALES Ecos de La bamba. Una historia etnomusicológica sobre el son jarocho del centro - sur de Veracruz, 1946 -1959. TESIS Que para optar el grado de: DOCTOR EN HISTORIA Y ESTUDIOS REGIONALES PRESENTA: Randall Ch. Kohl S. Director de tesis: Dr. Ernesto Isunza Vera Xalapa, Veracruz Mayo de 2004 * { ■,>■£$■ f t JúO t Agradecimientos......................................................... ..................................................... iii Dedicatoria...........................................................................................................................iv Capítulo I Introducción......................................................................................................1 1) Límites temporales y espaciales...................................... ........................... 2 2) Construcción de la región musical y marco teórico...................................6 3) Definiciones de términos................................................ .............................. 10 4) Revisión de la literatura existente.................................................................14 5) Metodología y fuentes primarias...................................................................19 6) Organización....................................................................................................35 Capítulo II El alemanismo y el son jarocho...................................................................37 -

Perspectives on New Wave Cumbia | Norient.Com 7 Oct 2021 06:12:57

Perspectives on New Wave Cumbia | norient.com 7 Oct 2021 06:12:57 Perspectives on New Wave Cumbia by Moses Iten Since the beginning of the 21st century «new wave cumbia» has been growing as an independent club culture simultaneously in several parts of the world. Innovative producers have reinvented the dance music-style cumbia and thus produced countless new subgenres. The common ground: they mix traditional Latin American cumbia-rhythms with rough electronic sounds. An insider perspective on a rapid evolution. From the Norient book Out of the Absurdity of Life (see and order here). https://norient.com/stories/new-wave-cumbia Page 1 of 15 Perspectives on New Wave Cumbia | norient.com 7 Oct 2021 06:12:58 Dreams are made of being at the right place at the right time and in early June 2007 I happened to arrive in Tijuana, Mexico. Tijuana had been proclaimed a new cultural Mecca by the US magazine Newsweek, largely due to the output of a group of artists called Nortec Collective and inadvertently spawned a new scene – a movement – called nor-tec (Mexican norteno folk music and techno). In 2001, the release of the compilation album Nortec Collective: The Tijuana Sessions Vol.1 (Palm Pictures) catapulted Tijuana from its reputation of being a sleazy, drug-crime infested Mexico/US border town to the frontline of hipness. Instantly it was hailed as a laboratory for artists exploring the clash of worlds: haves and have-nots, consumption and its leftovers, South meeting North, developed vs. underdeveloped nations, technology vs. folklore. After having hosted some of the first parties in Australia featuring members of the Nortec Collective back in 2005 and 2006, the connection was made.