Downloads.Html [Accessed November 29, 2011]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67

Listening in Double Time: Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67 Marc Howard Medwin A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2008 Approved by: David Garcia Allen Anderson Mark Katz Philip Vandermeer Stefan Litwin ©2008 Marc Howard Medwin ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT MARC MEDWIN: Listening in Double Time: Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67 (Under the direction of David F. Garcia). The music of John Coltrane’s last group—his 1965-67 quintet—has been misrepresented, ignored and reviled by critics, scholars and fans, primarily because it is a music built on a fundamental and very audible disunity that renders a new kind of structural unity. Many of those who study Coltrane’s music have thus far attempted to approach all elements in his last works comparatively, using harmonic and melodic models as is customary regarding more conventional jazz structures. This approach is incomplete and misleading, given the music’s conceptual underpinnings. The present study is meant to provide an analytical model with which listeners and scholars might come to terms with this music’s more radical elements. I use Coltrane’s own observations concerning his final music, Jonathan Kramer’s temporal perception theory, and Evan Parker’s perspectives on atomism and laminarity in mid 1960s British improvised music to analyze and contextualize the symbiotically related temporal disunity and resultant structural unity that typify Coltrane’s 1965-67 works. -

Newly Cataloged Items in the Music Library August - December 2017

Newly Cataloged Items in the Music Library August - December 2017 Call Number Author Title Publisher Enum Publication Date MUSIC. MCD3.C63 B37 v.1 Vivaldi, Antonio, 1678- Vivaldi : Venetian splendour. International Masters 2006 2006 1741. Pub., MUSIC. MCD3.C63 B37 v.2 Bach, Johann Sebastian, Bach : Baroque masterpieces. International Masters 2005 2005 1685-1750. Pub., MUSIC. MCD3.C63 B37 v.3 Bach, Johann Sebastian, Bach : master musician. International Masters 2007 2007 1685-1750. Pub., MUSIC. MCD3.C63 B37 v.5 Handel, George Frideric, Handel : from opera to oratorio. International Masters 2006 2006 1685-1759. Pub., MUSIC. MCD3.C63 C63 v.1 Haydn, Joseph, 1732- Haydn : musical craftsman. International Masters 2006 2006 1809. Pub., MUSIC. MCD3.C63 C63 v.2 Haydn, Joseph, 1732- Haydn : master of music. International Masters 2006 2006 1809. Pub., MUSIC. MCD3.C63 C63 v.3 Mozart, Wolfgang Mozart : musical masterpieces. International Masters 2005 2005 Amadeus, 1756-1791. Pub., MUSIC. MCD3.C63 C63 v.4 Mozart, Wolfgang Mozart : classic melodies. International Masters 2005 2005 Amadeus, 1756-1791. Pub., MUSIC. MCD3.C63 C63 v.5 Mozart, Wolfgang Mozart : magic of music. International Masters 2007 2007 Amadeus, 1756-1791. Pub., MUSIC. MCD3.C63 E17 .1 Beethoven, Ludwig van, Beethoven : the spirit of freedom. International Masters 2005 2005 1770-1827. Pub., MUSIC. MCD3.C63 E17 Rossini, Gioacchino, Rossini : opera and overtures. International Masters 2006 v.10 2006 1792-1868. Pub., MUSIC. MCD3.C63 E17 Schumann, Robert, 1810- Schumann : poetry and romance. International Masters 2006 v.11 2006 1856. Pub., MUSIC. MCD3.C63 E17 Mendelssohn-Bartholdy, Mendelssohn : dreams and fantasies. International Masters 2005 v.12 2005 Felix, 1809-1847. -

Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage

Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage Aaron Joseph Johnson Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Aaron Joseph Johnson All rights reserved ABSTRACT Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage Aaron Joseph Johnson This dissertation is a study of jazz on American radio. The dissertation's meta-subjects are mediation, classification, and patronage in the presentation of music via distribution channels capable of reaching widespread audiences. The dissertation also addresses questions of race in the representation of jazz on radio. A central claim of the dissertation is that a given direction in jazz radio programming reflects the ideological, aesthetic, and political imperatives of a given broadcasting entity. I further argue that this ideological deployment of jazz can appear as conservative or progressive programming philosophies, and that these tendencies reflect discursive struggles over the identity of jazz. The first chapter, "Jazz on Noncommercial Radio," describes in some detail the current (circa 2013) taxonomy of American jazz radio. The remaining chapters are case studies of different aspects of jazz radio in the United States. Chapter 2, "Jazz is on the Left End of the Dial," presents considerable detail to the way the music is positioned on specific noncommercial stations. Chapter 3, "Duke Ellington and Radio," uses Ellington's multifaceted radio career (1925-1953) as radio bandleader, radio celebrity, and celebrity DJ to examine the medium's shifting relationship with jazz and black American creative ambition. -

Perceptions of Meaningfulness Among High School Instrumental

Perceptions of Meaningfulness Among High School Instrumental Musicians by Janet Cape A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts Approved January 2012 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Sandra Stauffer, Chair Jeffrey Bush Margaret Schmidt Jill Sullivan Evan Tobias ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY May 2012 ABSTRACT The purpose of this multiple case study was to investigate what students in three high school music groups perceived as most meaningful about their participation. I also examined the role that context played in shaping students’ perceptions, and sought potential principles underlying meaning and value in instrumental ensembles. Over the course of six months I conducted a series of in-depth, semi- structured interviews with six student wind ensemble members, five student guitar class members, and six jazz band members at three high schools in Winnipeg, Canada. I interviewed the participants’ music teachers and school principals, observed rehearsals and performances, and spoke informally with parents and peers. Drawing upon praxial and place philosophies, I examined students’ experiences within the context of each music group, and looked for themes across the three groups. What students perceived to be meaningful about their participation was multifaceted and related to fundamental human concerns. Students valued opportunities to achieve, to form and strengthen relationships, to construct identities as individuals and group members, to express themselves and communicate with others, and to engage with and through music. Although these dimensions were common to students in all three groups, students experienced and made sense of them differently, and thus experienced meaningful participation in multiple, variegated ways. -

David Liebman Papers and Sound Recordings BCA-041 Finding Aid Prepared by Amanda Axel

David Liebman papers and sound recordings BCA-041 Finding aid prepared by Amanda Axel This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit November 30, 2018 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Berklee Archives Berklee College of Music 1140 Boylston St Boston, MA, 02215 617-747-8001 David Liebman papers and sound recordings BCA-041 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Biographical/Historical note.......................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Contents note............................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement note...........................................................................................................................................4 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................5 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................6 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 7 Scores and Charts................................................................................................................................... -

Canada 14Usic

TTItr CAI{ADIAAT MUSIC TtrACHER LE PROFESSET_IR DE MUSTQUE CANADTEN oF Muslc lE4c,,eaa. -{f€o€FAnoN r"*2.,fo* c-ffi'r,A % 'W' o CFMTA tt^n't*f*ff#**.*d FCAPM CANADA 14USIC otfft'" t*""t""'ru" -rr$teoeRerto* "\ "".- cFffisl-A iwr 7 CONTTNIS n-*"^"F"#HM.,".."d h|EEK* Greetings from CFMT4....................... 3 Pyovincial Co-ordinators ............ ..........4 Canada Music WeekrM Supplies ............5 LA SEMAINE DE LA MUSIOUE CANADIENNE Diamond Jubilee CoIIection .................6 From the Provinces ..............................8 Editing Your Composition,................13 M)'sten' Music ....,.............14 Lessons With Yiolet fucher................I5 Inten'ierv u'ith Nlartin Beaver.............16 Classical trlusic Comes to lvlanitoulin ............ ........21 The Forsvths...,.,......... ......23 Music and Creativin' ............ ..............27 Music Writing Competition ...............29 1999 Provincial Winners ............ ........29 Music Writing Competition Regulations...............30 Music Writing Entry Form........ .........32 Music Writing Competition Winners .......33 Reviervs.... ........37 Music Qui2......... ..............39 - I - Executive Directory ..........40 NOVEMBEP 19 26 ' 2OAO P 26 NOVEMBPE Advertising Rate Card. ......42 The Prcven Theory Series It's the proven series to help your students learn, understand, enjoy and excel on RCM exams. Written by one of Canada's leading theorists and the former head of exams for the Royal Conservatory. The Lawless Theory Series Tnk,tl ,i Getting off to the right start... This -

JOURNAL of the AMERICAN THEATRE ORGAN SOCIETY Orbil ID™E Eclronic 1Ynrhe1izer P,UJ ~ -~Oh Xe01pinel Orgon Equoj

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN THEATRE ORGAN SOCIETY Orbil ID™e eclronic 1ynrhe1izer P,UJ ~ -~oh_xe01pinel orgon equoJ... rhenewe;I woy lo mo <.emu1ic fromWur irzec Now with the Orbit III electronic synthesizer from slowly, just as the theatre organist did by opening and Wurlitzer you can create new synthesized sounds in closing the chamber louvers. stantly ... in performance. And with the built-in Orbit III synthesizer, this This new Wurlitzer instrument is also a theatre organ, instrument can play exciting combinations of synthe with a sectionalized vibrato/tremolo, toy counter, in sized, new sounds, along with traditional organ music. A dependent tibias on each keyboard and the penetrating built-in cassette player/recorder lets you play along with kinura voice that all combine to recreate the sounds of pre-recorded tapes for even more dimensions in sound. the twenty-ton Mighty Wurlitzers of silent screen days. But you've got to play the Orbit III to believe it. And it's a cathedral/classical organ, too, with its own in Stop in at your Wurlitzer dealer and see the Wurlitzer dividually voiced diapason, reed, string and flute voices. 4037 and 4373. Play the eerie, switched-on sounds New linear accent controls permit you to increase or of synthesized music. Ask for your free Orbit III decrease the volume of selected sections suddenly, or demonstration record. Or write: Dep t: 1072 WURLilzER ® The Wurlitzer Company, DeKalb, Illinois 60115. ha.4'1he ,vay cover- photo ... Genii's console, the 3/13 235 Special Wurlitzer with Brass Trumpet, was installed in the Canal Street Theatre in New York in 1927, and was moved to the Triboro The atre in Queens, New York in 1931. -

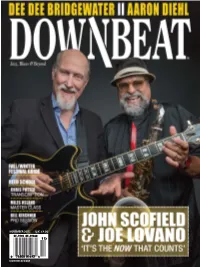

Downbeat.Com November 2015 U.K. £4.00

NOVEMBER 2015 2015 NOVEMBER U.K. £4.00 DOWNBEAT.COM DOWNBEAT JOHN SCOFIELD « DEE DEE BRIDGEWATER « AARON DIEHL « ERIK FRIEDLANDER « FALL/WINTER FESTIVAL GUIDE NOVEMBER 2015 NOVEMBER 2015 VOLUME 82 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer ĺDQHWDÎXQWRY£ Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Bookkeeper Emeritus Margaret Stevens Editorial Assistant Stephen Hall Editorial Intern Baxter Barrowcliff ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sam Horn 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; -

August 1910) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 8-1-1910 Volume 28, Number 08 (August 1910) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 28, Number 08 (August 1910)." , (1910). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/561 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CELEBRATED CONTRIBUTORS TO THE ETUDE KJiAkt U THE ETVDE AUGUST 1910 Theo. PresserCo.. Philadelphia.Pa. 501 STUDIES IN OCTAVES | THE ETUDE New ADVANCED PASSAGE-WORK Publications EIGHT MELODIOUS STUDIES IN MODERN TECHNIC Premiums and Special Offers Easy Engelmann Album By CEZA HORVATH Singers’ Repertoire Studies for the Lett Hand Op. 87, Price $ 1.25 Crade IV-V FOR THE PIANO These « are in gM of Interest to Our Readers A Collection of Sacred end Secular Alone k. MONTHLY JOURNAL FOR THE MUSICIAN, T Songs for Medium Voice Price. 50 Cents MUSIC STUDENT, AND ALL MUSIC LOVERS. Price. 50 Cents For the Pianoforte Edited by .TAMES FRANCIS COOKE Twenty-six of Mr. -

JAZZ: a Regional Exploration

JAZZ: A Regional Exploration Scott Yanow GREENWOOD PRESS JAZZ A Regional Exploration GREENWOOD GUIDES TO AMERICAN ROOTS MUSIC JAZZ A Regional Exploration Scott Yanow Norm Cohen Series Editor GREENWOOD PRESS Westport, Connecticut • London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Yanow, Scott. Jazz : a regional exploration / Scott Yanow. p. cm. – (Greenwood guides to American roots music, ISSN 1551-0271) Includes bibliographical references and index. Discography: p. ISBN 0-313-32871-4 (alk. paper) 1 . Jazz—History and criticism. I. Title. II. Series. ML3508.Y39 2005 781.65'0973—dc22 2004018158 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2005 by Scott Yanow All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2004018158 ISBN: 0-313-32871-4 ISSN: 1551-0271 First published in 2005 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48-1984). 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents Series Foreword vii Preface xi Chronology xiii Introduction xxiii 1. Sedalia and St. Louis: Ragtime 1 2. New Orleans Jazz 7 3. Chicago: Classic Jazz 15 4. New York: The Classic Jazz and Swing Eras 29 5. Kansas City Swing, the Territory Bands, and the San Francisco Revival 99 6. New York Bebop, Latin, and Cool Jazz 107 7. -

JAZZ EDUCATION in ISRAEL by LEE CAPLAN a Thesis Submitted to The

JAZZ EDUCATION IN ISRAEL by LEE CAPLAN A Thesis submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History and Research written under the direction of Dr. Henry Martin and approved by ___________________________________ ___________________________________ Newark, New Jersey May,2017 ©2017 Lee Caplan ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS JAZZ EDUCATION IN ISRAEL By LEE CAPLAN Thesis Director Dr. Henry Martin Jazz Education in Israel is indebted to three key figures – Zvi Keren, Arnie Lawrence, and Mel Keller. This thesis explores how Jazz developed in Israel and the role education played. Jazz Education in Israel discusses the origin of educational programs such as the Rimon School of Jazz and Contemporary Music (1985) and the New School Jazz Program (1986). One question that was imperative to this study was attempting to discover exactly how Jazz became a cultural import and export within Israel. Through interviews included in this thesis, this study uncovers just that. The interviews include figures such as Tal Ronen, Dr. Arnon Palty, Dr. Alona Sagee, and Keren Yair Dagan. As technology gets more advanced and the world gets smaller, Jazz finds itself playing a larger role in humanity as a whole. iii Preface The idea for this thesis came to me when I was traveling abroad during the summer of 2015. I was enjoying sightseeing throughout the streets of Ben Yehuda Jerusalem contemplating topics when all of a sudden I came across a jam session. I went over to listen to the music and was extremely surprised to find musicians from all parts of Europe coming together in a small Jazz venue in Israel playing bebop standards at break-neck speeds. -

Primary Sources: an Examination of Ira Gitler's

PRIMARY SOURCES: AN EXAMINATION OF IRA GITLER’S SWING TO BOP AND ORAL HISTORY’S ROLE IN THE STORY OF BEBOP By CHRISTOPHER DENNISON A thesis submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers University, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements of Master of Arts M.A. Program in Jazz History and Research Written under the direction of Dr. Lewis Porter And approved by ___________________________ _____________________________ Newark, New Jersey May, 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Primary Sources: An Examination of Ira Gitler’s Swing to Bop and Oral History’s Role in the Story of Bebop By CHRISTOPHER DENNISON Thesis director: Dr. Lewis Porter This study is a close reading of the influential Swing to Bop: An Oral History of the Transition of Jazz in the 1940s by Ira Gitler. The first section addresses the large role oral history plays in the dominant bebop narrative, the reasons the history of bebop has been constructed this way, and the issues that arise from allowing oral history to play such a large role in writing bebop’s history. The following chapters address specific instances from Gitler’s oral history and from the relevant recordings from this transitionary period of jazz, with musical transcription and analysis that elucidate the often vague words of the significant musicians. The aim of this study is to illustratethe smoothness of the transition from swing to bebop and to encourage a sense of skepticism in jazz historians’ consumption of oral history. ii Acknowledgments The biggest thanks go to Dr. Lewis Porter and Dr.