Jceslaus SIPOVICH in MEMORIAM~

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BIOGRAPHY- the LONDON ORATORY CHOIRS the London

BIOGRAPHY- THE LONDON ORATORY CHOIRS The London Oratory, also known as the Brompton Oratory, has three distinct and reputable choirs, all of which are signed to recording label AimHigher Recordings which is distributed worldwide by Sony Classical. THE LONDON ORATORY SCHOLA CANTORUM BOYS CHOIR was founded in 1996. Educated in the Junior House of the London Oratory School, boys from the age of 7 are given outstanding choral and instrumental training within a stimulating musical environment. Directed by Charles Cole, the prestigious ‘Schola’ is regarded as one of London’s leading boy-choirs, in demand for concert and soundtrack work. The London Oratory Schola Cantorum Boys Choir will be the first choir to release an album under a new international recording partnership with AimHigher Recordings/Sony Classical. The debut album of the major label arrangement, due out February 10, 2017, will be entitled Sacred Treasures of England. THE CHOIR OF THE LONDON ORATORY is the UK’s senior professional choir and sings for all the major liturgies at the Oratory. Comprising some of London’s leading ensemble singers, the choir is internationally renowned. The choir is regularly featured on live broadcasts of Choral Vespers on BBC Radio 3 and its working repertoire covers all aspects and periods of music for the Latin Rite from Gregorian chant to the present day with special emphasis on 16th and 17th century polyphony and the Viennese classical Mass repertory of the late 18th and 19th centuries. The Choir is directed by Patrick Russill, who serves as The London Oratory’s Director of Music and is also Head of Choral Conducting at London's Royal Academy of Music. -

A4 Web Map 26-1-12:Layout 1

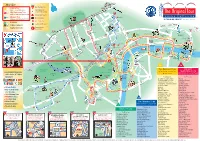

King’s Cross Start St Pancras MAP KEY Eurostar Main Starting Point Euston Original Tour 1 St Pancras T1 English commentary/live guides Interchange Point City Sightseeing Tour (colour denotes route) Start T2 W o Language commentaries plus Kids Club REGENT’S PARK Euston Rd b 3 u Underground Station r n P Madame Tussauds l Museum Tour Russell Sq TM T4 Main Line Station Gower St Language commentaries plus Kids Club q l S “A TOUR DE FORCE!” The Times, London To t el ★ River Cruise Piers ss Gt Portland St tenham Ct Rd Ru Baker St T3 Loop Line Gt Portland St B S s e o Liverpool St Location of Attraction Marylebone Rd P re M d u ark C o fo t Telecom n r h Stansted Station Connector t d a T5 Portla a m Museum Tower g P Express u l p of London e to S Aldgate East Original London t n e nd Pl t Capital Connector R London Wall ga T6 t o Holborn s Visitor Centre S w p i o Aldgate Marylebone High St British h Ho t l is und S Museum el Bank of sdi igh s B tch H Gloucester Pl s England te Baker St u ga Marylebone Broadcasting House R St Holborn ld d t ford A R a Ox e re New K n i Royal Courts St Paul’s Cathedral n o G g of Justice b Mansion House Swiss RE Tower s e w l Tottenham (The Gherkin) y a Court Rd M r y a Lud gat i St St e H n M d t ill r e o xfo Fle Fenchurch St Monument r ld O i C e O C an n s Jam h on St Tower Hill t h Blackfriars S a r d es St i e Oxford Circus n Aldwyc Temple l a s Edgware Rd Tower Hil g r n Reg Paddington P d ve s St The Monument me G A ha per T y Covent Garden Start x St ent Up r e d t r Hamleys u C en s fo N km Norfolk -

The Holy See

The Holy See LETTER OF HIS HOLINESS POPE FRANCIS TO THE BISHOPS OF INDIA Dear Brother Bishops, 1. The remarkable varietas Ecclesiarum, the result of a long historical, cultural, spiritual and disciplinary development, constitutes a treasure of the Church, regina in vestitu deaurato circumdata varietate (cf. Ps 44 and Leo XIII, Orientalium Dignitas), who awaits her groom with the fidelity and patience of the wise virgin, equipped with an abundant supply of oil, so that the light of her lamp may enlighten all peoples in the long night of awaiting the Lord’s coming. This variety of ecclesial life, which shines with great splendour throughout lands and nations, is also found in India. The Catholic Church in India has its origins in the preaching of the Apostle Thomas. It developed through contact with the Churches of Chaldean and Antiochian traditions and through the efforts of Latin missionaries. The history of Christianity in this great country thus led to three distinct sui iuris Churches, corresponding to ecclesial expressions of the same faith celebrated in different rites according to the three liturgical, spiritual, theological and disciplinary traditions. Although this situation has sometimes led to tensions in the course of history, today we can admire a Christian presence that is both rich and beautiful, complex and unique. 2. It is essential for the Catholic Church to reveal her face in all its beauty to the world, in the richness of her various traditions. For this reason the Congregation for the Oriental Churches, which celebrates its centenary year, having been established through the farsightedness of Pope Benedict XV in 1917, has encouraged, where necessary, the restoration of Eastern Catholic traditions, and ensured their protection, as well as respect for the dignity and rights of these ancient Churches. -

Brompton Conservation Area Appraisal

Brompton Conservation Area Appraisal September 2016 Adopted: XXXXXXXXX Note: Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of this document but due to the complexity of conservation areas, it would be impossible to include every facet contributing to the area’s special interest. Therefore, the omission of any feature does not necessarily convey a lack of significance. The Council will continue to assess each development proposal on its own merits. As part of this process a more detailed and up to date assessment of a particular site and its context is undertaken. This may reveal additional considerations relating to character or appearance which may be of relevance to a particular case. BROMPTON CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL | 3 Contents 1. INTRODUCTION 4 Other Building Types 25 Summary of Special Interest Places of Worship Location and Setting Pubs Shops 2. TOWNSCAPE 6 Mews Recent Architecture Street Layout and Urban Form Gaps Land Uses 4. PUBLIC REALM 28 Green Space Street Trees Materials Street Surfaces Key Dates Street Furniture Views and Landmarks 3. ARCHITECTURE 14 5. NEGATIVE ELEMENTS 32 Housing Brompton Square Brompton Road APPENDIX 1 History 33 Cheval Place APPENDIX 2 Historic England Guidance 36 Ennismore Street Montpelier Street APPENDIX 3 Relevant Local Plan Policies 37 Rutland Street Shared Features Of Houses 19 Architectural Details Rear Elevations Roofs Front Boundaries and Front Areas Gardens and Garden Trees 4 | BROMPTON CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL 1 Introduction ² Brompton Conservation Area What does a conservation area designation mean? City of 1.1 The statutory definition of a conservation n n Westminster w o o i area is an “area of special architectural or historic T t 1979 a s v n r a a e e interest, the character or appearance of which it H s r n A o is desirable to preserve or enhance”. -

The Classical Rite of the Catholic Church a Sermon Preached at the Launch of CIEL UK at St

The Classical Rite of the Catholic Church A sermon preached at the launch of CIEL UK at St. James' Spanish Place, Saturday 1st March, 1997 by Fr. Ignatius Harrison Provost of Brompton Oratory. he things we have heard and understood the things our fathers have told us, T these we will not hide from their children but will tell them to the next generation... He gave a command to our fathers to make it known to their children that the next generation might know it, the children yet to be born .- Psalm 77 FOR those of us who love the classical Roman rite, the last few years have been a time of great encouragement. The Holy Father has made it abundantly clear that priests and laity who are attached to the traditional liturgy must have access to it, and to do so is a legitimate aspiration. Many bishops and prelates have not only celebrated the traditional Mass themselves, but have enabled pastoral and apostolic initiatives within their dioceses, initiatives that make the classical liturgy increasingly accessible. Growing numbers of younger priests who do not remember the pre-conciliar days are discovering the beauty and prayerfulness of the classical forms. Religious communities which have the traditional rites as their staple diet are flourishing, blessed with many vocations. Thousands upon thousands of the faithful are now able to attend the traditional Mass regularly, in full and loyal communion with their bishop in full and loyal communion with the Sovereign Pontiff, the Vicar of Christ. All this, we must believe, is the work of the Lord and it is marvellous in our eyes. -

The Concept of “Sister Churches” in Catholic-Orthodox Relations Since

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA The Concept of “Sister Churches” In Catholic-Orthodox Relations since Vatican II A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Theology and Religious Studies Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy © Copyright All Rights Reserved By Will T. Cohen Washington, D.C. 2010 The Concept of “Sister Churches” In Catholic-Orthodox Relations since Vatican II Will T. Cohen, Ph.D. Director: Paul McPartlan, D.Phil. Closely associated with Catholic-Orthodox rapprochement in the latter half of the 20 th century was the emergence of the expression “sister churches” used in various ways across the confessional division. Patriarch Athenagoras first employed it in this context in a letter in 1962 to Cardinal Bea of the Vatican Secretariat for the Promotion of Christian Unity, and soon it had become standard currency in the bilateral dialogue. Yet today the expression is rarely invoked by Catholic or Orthodox officials in their ecclesial communications. As the Polish Catholic theologian Waclaw Hryniewicz was led to say in 2002, “This term…has now fallen into disgrace.” This dissertation traces the rise and fall of the expression “sister churches” in modern Catholic-Orthodox relations and argues for its rehabilitation as a means by which both Catholic West and Orthodox East may avoid certain ecclesiological imbalances toward which each respectively tends in its separation from the other. Catholics who oppose saying that the Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church are sisters, or that the church of Rome is one among several patriarchal sister churches, generally fear that if either of those things were true, the unicity of the Church would be compromised and the Roman primacy rendered ineffective. -

St. John XXIII Feast: October 11

St. John XXIII Feast: October 11 Facts Feast Day: October 11 Patron: of Papal delegates, Patriarchy of Venice, Second Vatican Council Birth: 1881 Death: 1963 Beatified: 3 September 2000 by Pope John Paul II Canonized: 27 April 2014 Saint Peter's Square, Vatican City by Pope Francis The man who would be Pope John XXIII was born in the small village of Sotto il Monte in Italy, on November 25, 1881. He was the fourth of fourteen children born to poor parents who made their living by sharecropping. Named Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli, the baby would eventually become one of the most influential popes in recent history, changing the Church forever. Roncalli's career within the Church began in 1904 when he graduated from university with a doctorate in theology. He was ordained a priest thereafter and soon met Pope Pius X in Rome. By the following year, 1905, Roncalli was appointed to act as secretary for his bishop, Giacomo Radini-Tedeschi. He continued working as the bishop's secretary until the bishop died in August 1914. The bishop's last words to Roncalli were, "Pray for peace." Such words mattered in August 1914 as the world teetered on the brink of World War I. Italy was eventually drawn into the war and Roncalli was drafted into the Italian Army as a stretcher bearer and chaplain. Roncalli did his duty and was eventually discharged from the army in 1919. Free to serve the Church in new capacities he was appointed to be the Italian president of the Society for the Propagation of the Faith, handpicked by Pope Benedict XV. -

The Brompton Oratory, London, England

Tridentine Community News April 16, 2006 Glorious Day, Glorious Church: had concluded in St. Wilfrid’s Chapel. Stop and consider The Brompton Oratory, London that: Multiple Tridentine Masses occurring on a Saturday in one church, while we are presently permitted only one per Today, as we celebrate the Resurrection of Our Lord, it is week each in Windsor and Detroit. fitting that we discuss one of the most glorious Catholic churches operating in our age, the Oratory of St. Philip Neri Fans of the Harry Potter movies will be interested to learn on Brompton Road in London, England. that the Hogwarts School Choir occasionally featured in the films is actually the London Oratory Junior Choir. That London itself is arguably the most liturgically sophisticated choir sings at, among other things, the weekly Tuesday night city in Christendom. Future columns will address the many Benediction service that follow the 6:00 PM Novus Ordo other wonders of Roman Catholic London. But any Latin Mass. How impressive to see a 40 member choir discussion of her treasures processing in on a Tuesday must begin with the night! Oratory, ground zero for the reverent celebration of Sundays are major events. the Holy Sacrifice of the At 9:00 AM, a Tridentine Mass according to both the Mass is celebrated at the Novus Ordo and high altar. At 11:00 AM, a Tridentine rites. Solemn Novus Ordo Latin Mass with a professional Almost any discussion of choir attracts a standing- the Tridentine Mass will room only congregation. sooner or later reference At 3:00 PM, Solemn the famous statement of Fr. -

6 Easter in Detention Andrew Hamilton

6 April 2012 Volume: 22 Issue: 6 Easter in detention Andrew Hamilton .........................................1 Easter manifesto John Falzon .............................................3 What Australia doesn’t want East Timor to know Pat Walsh .............................................. 5 Titanic sets human tragedy apart from Hollywood gloss Tim Kroenert ............................................7 A Mormon in the White House Alan Gill .............................................. 9 Russia’s liberal wind of change Dorothy Horsfield ........................................ 12 Australia’s mystic river Various ............................................... 14 Targeting aid workers Duncan Maclaren ........................................ 17 The age pension was fairer than super Brian Tooohey .......................................... 19 Bob Carr’s ‘overlap of cultures’ and the Victorian bishops on gay marriage Michael Mullins ......................................... 22 Close-ish encounters with two queens Brian Matthews ......................................... 24 Canned pairs reveal Opposition’s fruity strategy John Warhurst .......................................... 26 US bishops’ contraception conundrum Andrew Hamilton ........................................ 28 Geriatric sex and dignity Tim Kroenert ........................................... 31 Revelations shed new light on Bill Morris dismissal Frank Brennan .......................................... 33 Greek peasant’s faithful fatalism Gillian Bouras ......................................... -

Substantial Grade Ii Listed Georgian House Located in a Prime Knightsbridge Garden Square Knightsbridge Garden Square

SUBSTANTIAL GRADE II LISTED GEORGIAN HOUSE LOCATED IN A PRIME KNIGHTSBRIDGE GARDEN SQUARE KNIGHTSBRIDGE GARDEN SQUARE. A WONDERFUL GEORGIAN HOUSE WITH PLANNING PERMISSION TO SUBSTANTIALLY EXTEND BROMPTON SQUARE LONDON , SW3 Guide Price £15,950,000, Freehold 4 reception rooms • 7 bedrooms • 6 bathrooms Kitchen/breakfast room • Conservatory Gymnasium Lift Situation Brompton Square is located in Knightsbridge, north of Brompton Road and immediately east of the Brompton Oratory. The location has good transport connections, being equidistant from Knightsbridge (Piccadilly line) and South Kensington (district, circle and Piccadilly lines) underground stations are close by and easily accessible. There are many bus routes along Brompton Road. London's West End is easily accessible to the east, along Brompton Road (A4) with the national motorway network and London's Heathrow Airport to the west along Cromwell Road (A4). There are excellent local shopping and restaurant facilities nearby including Harrods and Harvey Nicholls. A selection of internationally renowned shops and boutiques can be found nearby in Beauchamp Place, Walton Street and Fulham Road. To the north of the house, Hyde Park is easily accessible. Description The houses at the northern end of Brompton Square were laid out between 1824 to 1839. They are arranged on a curve at the end of the square with stucco fronted elevations, enriched windows, projecting porches with Doric columns. This Grade II listed house is 2 windows wide having a cast iron balcony to the first floor overlooking the square gardens. The house currently extends to approximately 6,359 sq ft (591 sq m) and is arranged over lower ground, ground and 4 upper floors. -

Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky's Detentions Under Russia and Poland

Logos: A Journal of Eastern Christian Studies Vol. 50 (2009) Nos. 1–2, pp. 13–54 A Prisoner for His People’s Faith: Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky’s Detentions under Russia and Poland Athanasius D. McVay Abstract (Українське резюме на ст. 53) Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky (1865–1944) was impri- soned no fewer than three times because of his defence of the faith of his Ukrainian people. Based on correspondence found in the Vatican Archives, this article reveals hitherto unknown details of the metropolitan’s imprisonments. It also sheds light on the reasons why Sheptytsky was imprisoned so many times and chronicles the vigorous interventions of the Roman Apos- tolic See to defend the metropolitan and to secure his release and return to his archeparchy of Lviv. His personal back- ground, spiritual journey, and persecution, closely parallel aspects of the history of the Ukrainian nation. He underwent his own process of national awakening, which resulted in his return to the Byzantine-Ruthenian rite of his ancestors. Be- coming Byzantine yet remaining Catholic placed him directly at odds with the political-religious ideologies of both the Russian Empire and the newborn Polish Republic, especially since he had assumed the mantle of spiritual leadership over the Galician Ukrainians. Sheptytsky was deported to Siberia in 1914 as an obstacle to the tsarist plan to absorb the Ukrai- nian Greco-Catholics into the Russian Orthodox Church. In 1919, he was placed under house arrest, this time by Catholic Poland, and interned three years later by the same government when he attempted to return to Lviv. ®®®®®®®® 14 Athanasius D. -

The Catholic Church and the Holocaust, 1930–1965 Ii Introduction Introduction Iii

Introduction i The Catholic Church and the Holocaust, 1930–1965 ii Introduction Introduction iii The Catholic Church and the Holocaust, 1930 –1965 Michael Phayer INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS Bloomington and Indianapolis iv Introduction This book is a publication of Indiana University Press 601 North Morton Street Bloomington, IN 47404-3797 USA http://www.indiana.edu/~iupress Telephone orders 800-842-6796 Fax orders 812-855-7931 Orders by e-mail [email protected] © 2000 by John Michael Phayer All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and re- cording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of Ameri- can University Presses’ Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Perma- nence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Phayer, Michael, date. The Catholic Church and the Holocaust, 1930–1965 / Michael Phayer. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-253-33725-9 (alk. paper) 1. Pius XII, Pope, 1876–1958—Relations with Jews. 2. Judaism —Relations—Catholic Church. 3. Catholic Church—Relations— Judaism. 4. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945) 5. World War, 1939– 1945—Religious aspects—Catholic Church. 6. Christianity and an- tisemitism—History—20th century. I. Title. BX1378 .P49 2000 282'.09'044—dc21 99-087415 ISBN 0-253-21471-8 (pbk.) 2 3 4 5 6 05 04 03 02 01 Introduction v C O N T E N T S Acknowledgments ix Introduction xi 1.