REGINALD MILLS SILBY the Westminster Connection [Slide 1]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNUAL REPORT 2020 Dear Friends

Catholic Community FOUNDATION OF MINNESOTA onlyCOMMUNION IN THE MIDST OF CRISIS together ANNUAL REPORT 2020 Dear Friends, None of us will forget 2020 anytime soon. The pandemic, together with the social unrest in the wake of George Floyd’s unjust death, have taken a heavy toll. At the same time, I’m very proud of how our Catholic community has responded. In the midst of dual crises, in a time of fear and uncertainty, we have come together to help our neighbors and support Catholic organizations. Only together can we achieve success, as Archbishop Hebda says, “On our own, there’s little that we’re able to accomplish. It’s only with collaboration, involving the thinking and generosity of many folks that we’re able to put together a successful plan.” The Catholic Community Foundation of Minnesota (CCF) has never been better prepared to meet the challenges of the moment. Within days of the suspension of public Masses in March, CCF established onlyCOMMUNION IN THE MIDST OF CRISIS the Minnesota Catholic Relief Fund. Immediately, hundreds of generous people made extraordinary donations to support our local Catholic community. Shortly thereafter, CCF began deploying monies to parishes and schools in urgent need. This was all possible because CCF had the operational and relational infrastructure in place to act swiftly: the connections, the trust, the expertise, and the overwhelming support of our donors. CCF has proven it’s just as capable of serving the long-term needs of our Catholic community. together Through our Legacy Fund and a variety of endowments, individuals can support Catholic ministries in perpetuity, while parishes partner with CCF to safeguard their long-term financial stability. -

Rejuvenating a Diocese Fr

VOL. 78 NO. 10 WWW.BISMARCKDIOCESE.COM NOVEMBER 2019 Dakota Catholic Action Reporting on Catholic action in western ND since 1941 Rejuvenating a diocese Fr. Vetter Remembering Bishop John Kinney named bishop By Sonia Mullally DCA Editor Father Austin A. Vetter was appointed When Bishop Kinney arrived in by Pope Francis on Oct. 8 as the Bishop of 1982, the young and lively priest was the Diocese of Helena, the Catholic diocese for fi lled with ideas and plans, set to western Montana. rejuvenate the diocese. Father Vetter is only He had been appointed an the second diocesan auxiliary bishop for the Archdiocese priest to be named of St. Paul-Minneapolis in January bishop — the fi rst 1977, at 39 years old, the youngest native of the Diocese bishop in the U.S. Five years later, in of Bismarck. The other 1982, he became the fi fth bishop of was Bishop Sylvester Fr. Austin A. Vetter Bismarck. In 1995, he was transferred Treinen, originally from to the Diocese of St. Cloud, Minn. Minnesota, who was ordained a priest of The native Minnesotan headed the Bismarck Diocese in 1946 and served the Diocese of St. Cloud until his here until being named Bishop of Boise, retirement in 2013. Idaho in 1962. Retired Bishop John Kinney of St. Bishop Kagan said of Fr. Vetter, “Thank Cloud died Sept. 27 while under the God that he has the courageous faith to say care of hospice. He was 82. ‘yes’ and be a shepherd of God’s people. He will do very well and he will always be Changing the structure a credit to Christ and our Church and to When Bishop Kinney took over the his home diocese.” Diocese of Bismarck, the diocesan Bishop-elect Vetter will be ordained and staff and offi ces were very minimal. -

BIOGRAPHY- the LONDON ORATORY CHOIRS the London

BIOGRAPHY- THE LONDON ORATORY CHOIRS The London Oratory, also known as the Brompton Oratory, has three distinct and reputable choirs, all of which are signed to recording label AimHigher Recordings which is distributed worldwide by Sony Classical. THE LONDON ORATORY SCHOLA CANTORUM BOYS CHOIR was founded in 1996. Educated in the Junior House of the London Oratory School, boys from the age of 7 are given outstanding choral and instrumental training within a stimulating musical environment. Directed by Charles Cole, the prestigious ‘Schola’ is regarded as one of London’s leading boy-choirs, in demand for concert and soundtrack work. The London Oratory Schola Cantorum Boys Choir will be the first choir to release an album under a new international recording partnership with AimHigher Recordings/Sony Classical. The debut album of the major label arrangement, due out February 10, 2017, will be entitled Sacred Treasures of England. THE CHOIR OF THE LONDON ORATORY is the UK’s senior professional choir and sings for all the major liturgies at the Oratory. Comprising some of London’s leading ensemble singers, the choir is internationally renowned. The choir is regularly featured on live broadcasts of Choral Vespers on BBC Radio 3 and its working repertoire covers all aspects and periods of music for the Latin Rite from Gregorian chant to the present day with special emphasis on 16th and 17th century polyphony and the Viennese classical Mass repertory of the late 18th and 19th centuries. The Choir is directed by Patrick Russill, who serves as The London Oratory’s Director of Music and is also Head of Choral Conducting at London's Royal Academy of Music. -

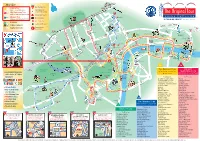

A4 Web Map 26-1-12:Layout 1

King’s Cross Start St Pancras MAP KEY Eurostar Main Starting Point Euston Original Tour 1 St Pancras T1 English commentary/live guides Interchange Point City Sightseeing Tour (colour denotes route) Start T2 W o Language commentaries plus Kids Club REGENT’S PARK Euston Rd b 3 u Underground Station r n P Madame Tussauds l Museum Tour Russell Sq TM T4 Main Line Station Gower St Language commentaries plus Kids Club q l S “A TOUR DE FORCE!” The Times, London To t el ★ River Cruise Piers ss Gt Portland St tenham Ct Rd Ru Baker St T3 Loop Line Gt Portland St B S s e o Liverpool St Location of Attraction Marylebone Rd P re M d u ark C o fo t Telecom n r h Stansted Station Connector t d a T5 Portla a m Museum Tower g P Express u l p of London e to S Aldgate East Original London t n e nd Pl t Capital Connector R London Wall ga T6 t o Holborn s Visitor Centre S w p i o Aldgate Marylebone High St British h Ho t l is und S Museum el Bank of sdi igh s B tch H Gloucester Pl s England te Baker St u ga Marylebone Broadcasting House R St Holborn ld d t ford A R a Ox e re New K n i Royal Courts St Paul’s Cathedral n o G g of Justice b Mansion House Swiss RE Tower s e w l Tottenham (The Gherkin) y a Court Rd M r y a Lud gat i St St e H n M d t ill r e o xfo Fle Fenchurch St Monument r ld O i C e O C an n s Jam h on St Tower Hill t h Blackfriars S a r d es St i e Oxford Circus n Aldwyc Temple l a s Edgware Rd Tower Hil g r n Reg Paddington P d ve s St The Monument me G A ha per T y Covent Garden Start x St ent Up r e d t r Hamleys u C en s fo N km Norfolk -

Brompton Conservation Area Appraisal

Brompton Conservation Area Appraisal September 2016 Adopted: XXXXXXXXX Note: Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of this document but due to the complexity of conservation areas, it would be impossible to include every facet contributing to the area’s special interest. Therefore, the omission of any feature does not necessarily convey a lack of significance. The Council will continue to assess each development proposal on its own merits. As part of this process a more detailed and up to date assessment of a particular site and its context is undertaken. This may reveal additional considerations relating to character or appearance which may be of relevance to a particular case. BROMPTON CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL | 3 Contents 1. INTRODUCTION 4 Other Building Types 25 Summary of Special Interest Places of Worship Location and Setting Pubs Shops 2. TOWNSCAPE 6 Mews Recent Architecture Street Layout and Urban Form Gaps Land Uses 4. PUBLIC REALM 28 Green Space Street Trees Materials Street Surfaces Key Dates Street Furniture Views and Landmarks 3. ARCHITECTURE 14 5. NEGATIVE ELEMENTS 32 Housing Brompton Square Brompton Road APPENDIX 1 History 33 Cheval Place APPENDIX 2 Historic England Guidance 36 Ennismore Street Montpelier Street APPENDIX 3 Relevant Local Plan Policies 37 Rutland Street Shared Features Of Houses 19 Architectural Details Rear Elevations Roofs Front Boundaries and Front Areas Gardens and Garden Trees 4 | BROMPTON CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL 1 Introduction ² Brompton Conservation Area What does a conservation area designation mean? City of 1.1 The statutory definition of a conservation n n Westminster w o o i area is an “area of special architectural or historic T t 1979 a s v n r a a e e interest, the character or appearance of which it H s r n A o is desirable to preserve or enhance”. -

The Classical Rite of the Catholic Church a Sermon Preached at the Launch of CIEL UK at St

The Classical Rite of the Catholic Church A sermon preached at the launch of CIEL UK at St. James' Spanish Place, Saturday 1st March, 1997 by Fr. Ignatius Harrison Provost of Brompton Oratory. he things we have heard and understood the things our fathers have told us, T these we will not hide from their children but will tell them to the next generation... He gave a command to our fathers to make it known to their children that the next generation might know it, the children yet to be born .- Psalm 77 FOR those of us who love the classical Roman rite, the last few years have been a time of great encouragement. The Holy Father has made it abundantly clear that priests and laity who are attached to the traditional liturgy must have access to it, and to do so is a legitimate aspiration. Many bishops and prelates have not only celebrated the traditional Mass themselves, but have enabled pastoral and apostolic initiatives within their dioceses, initiatives that make the classical liturgy increasingly accessible. Growing numbers of younger priests who do not remember the pre-conciliar days are discovering the beauty and prayerfulness of the classical forms. Religious communities which have the traditional rites as their staple diet are flourishing, blessed with many vocations. Thousands upon thousands of the faithful are now able to attend the traditional Mass regularly, in full and loyal communion with their bishop in full and loyal communion with the Sovereign Pontiff, the Vicar of Christ. All this, we must believe, is the work of the Lord and it is marvellous in our eyes. -

Jceslaus SIPOVICH in MEMORIAM~

jcESLAUS SIPOVICH IN MEMORIAM~ Downloaded from Brill.com09/25/2021 08:13:29AM via free access 4 THE JOURNAL OF BYELORUSSIAN STUDIES Ceslaus Sipovich 1914-1981 Downloaded from Brill.com09/25/2021 08:13:29AM via free access Bishop Ceslaus Sipovich 1914-1981 Bishop Ceslaus Sipovich, M.I.C., Titular Bishop of Mariamme and Apostolic Visitor of Byelorussians, died in London on Sunday 4 October 1981. His death, caused by a massive coronary, occurred during a meeting to mark the tenth anniversary of the Francis Skaryna Byelorussian Library and Museum, which he had founded. In his person Byelorussians have lost one of their most outstanding religious and national leaders of the century. One old frtend ex pressed the feelings of many when he said that for him the death of Bishop Sipovich marked the end of an era. Ceslaus Sipovich was born on 8 December 1914 into a farming family at Dziedzinka, a small village in the north-western corner of Byelorussia. At that particular time Byelorussia was incorporated in the Russian Empire, but some years later, as a result of changes brought about by the First World War, its western regions came under Polish rule. The parents of Ceslaus, Vincent (1877-1957) and Jadviha, born Tycka (1890-1974) were both Catholics. They had eight children, of whom five- four boys and one girl- survived, Ceslaus being the eldest. The life of a Byelorussian peasant was not easy, and children were expected at an early age to start to help their parents with the farm work. Ceslaus was no exception, and from that time on, throughout his entire life, he retained a love and respect for manual labour, especially that of a farmer. -

The Brompton Oratory, London, England

Tridentine Community News April 16, 2006 Glorious Day, Glorious Church: had concluded in St. Wilfrid’s Chapel. Stop and consider The Brompton Oratory, London that: Multiple Tridentine Masses occurring on a Saturday in one church, while we are presently permitted only one per Today, as we celebrate the Resurrection of Our Lord, it is week each in Windsor and Detroit. fitting that we discuss one of the most glorious Catholic churches operating in our age, the Oratory of St. Philip Neri Fans of the Harry Potter movies will be interested to learn on Brompton Road in London, England. that the Hogwarts School Choir occasionally featured in the films is actually the London Oratory Junior Choir. That London itself is arguably the most liturgically sophisticated choir sings at, among other things, the weekly Tuesday night city in Christendom. Future columns will address the many Benediction service that follow the 6:00 PM Novus Ordo other wonders of Roman Catholic London. But any Latin Mass. How impressive to see a 40 member choir discussion of her treasures processing in on a Tuesday must begin with the night! Oratory, ground zero for the reverent celebration of Sundays are major events. the Holy Sacrifice of the At 9:00 AM, a Tridentine Mass according to both the Mass is celebrated at the Novus Ordo and high altar. At 11:00 AM, a Tridentine rites. Solemn Novus Ordo Latin Mass with a professional Almost any discussion of choir attracts a standing- the Tridentine Mass will room only congregation. sooner or later reference At 3:00 PM, Solemn the famous statement of Fr. -

Substantial Grade Ii Listed Georgian House Located in a Prime Knightsbridge Garden Square Knightsbridge Garden Square

SUBSTANTIAL GRADE II LISTED GEORGIAN HOUSE LOCATED IN A PRIME KNIGHTSBRIDGE GARDEN SQUARE KNIGHTSBRIDGE GARDEN SQUARE. A WONDERFUL GEORGIAN HOUSE WITH PLANNING PERMISSION TO SUBSTANTIALLY EXTEND BROMPTON SQUARE LONDON , SW3 Guide Price £15,950,000, Freehold 4 reception rooms • 7 bedrooms • 6 bathrooms Kitchen/breakfast room • Conservatory Gymnasium Lift Situation Brompton Square is located in Knightsbridge, north of Brompton Road and immediately east of the Brompton Oratory. The location has good transport connections, being equidistant from Knightsbridge (Piccadilly line) and South Kensington (district, circle and Piccadilly lines) underground stations are close by and easily accessible. There are many bus routes along Brompton Road. London's West End is easily accessible to the east, along Brompton Road (A4) with the national motorway network and London's Heathrow Airport to the west along Cromwell Road (A4). There are excellent local shopping and restaurant facilities nearby including Harrods and Harvey Nicholls. A selection of internationally renowned shops and boutiques can be found nearby in Beauchamp Place, Walton Street and Fulham Road. To the north of the house, Hyde Park is easily accessible. Description The houses at the northern end of Brompton Square were laid out between 1824 to 1839. They are arranged on a curve at the end of the square with stucco fronted elevations, enriched windows, projecting porches with Doric columns. This Grade II listed house is 2 windows wide having a cast iron balcony to the first floor overlooking the square gardens. The house currently extends to approximately 6,359 sq ft (591 sq m) and is arranged over lower ground, ground and 4 upper floors. -

The Erosion of Priestly Fraternity in the Archdiocese of St. Paul & Minneapolis

The Erosion of Priestly Fraternity in the Archdiocese of St. Paul & Minneapolis The Spotless Bride and the Scattered Apostles White Paper (First Edition-Lent 2006) David Pence To the Priests, Deacons and Seminarians of the Archdiocese of St. Paul & Minneapolis CONTENTS I Purpose of the Paper II The Characters and the Timeline III National Events IV Living with the Legacy of Archbishop Roach Friendship, Vulgarity and Piety Bishop as Political Prophet The Sociology of Social Justice Humiliation and the “Gay Concordat” St. John Vianney Seminary V Psychology and the loss of the Christian narrative: Ken Pierre and Tom Adamson VI Coming out and the Easy Rector: Richard Pates VII McDonough to Korogi: Institutionalizing Corruption VIII Christensen: Living with Evil but Re-establishing Sacred Space St. Paul Seminary IX The Long Reign of the Vice Rectors: Moudry, Yetzer & Bowers X Paying back the feminists: Rectorix and the war against Masculinity and Fatherhood XI Collaborative Ministry and Congregationalist Ecclesiology: Defining away the priesthood and the loss of the sacred. XII Sexuality and Spirituality: Can we talk? (McDonough, Papesh & Krenik) XIII Two Professors who left (Bunnell and Sagenbrecht): Why were they mourned and where did they go? XIV Science and Sister Schuth: James Hill turning in his grave Ryan Erickson: How it happened XV Fr. Ron Bowers - a reason for contrition XVI Fr. Phil Rask - the missing Father XVII What Ryan Erickson learned about sex at the seminary - in his own words XVIII Lessons, Contrition and Amendment Three Resignations and Why XIX Monsignor Boxleitner: A unique ministry to orphans and prisoners XX Fr. -

THE LONDON ORATORY CATHOLIC CHURCH Brompton Road, London SW7 2RP Tel: 020 7808 0900 (9.00Am – 9.00Pm)

THE LONDON ORATORY CATHOLIC CHURCH Brompton Road, London SW7 2RP Tel: 020 7808 0900 (9.00am – 9.00pm). www.bromptonoratory.com Sunday 28th June 2015 – Saints Peter and Paul, Apostles SOLEMNITY OF SAINTS PETER AND PAUL TRANSFERRED In the Dioceses of England and Wales, the Solemnity of Saints Peter and Paul, Apostles will be celebrated next Sunday 28th June this year (not on its customary date, 29th June). All Masses will be at the usual Sunday times. There will be Solemn High Mass at 11am and Solemn Second Vespers of the feast at 3.30pm. PETER’S PENCE There is a box at the back of the Church for the annual diocesan collection of Peter’s Pence to support the charitable works of the Holy Father. APPEAL FOR PERSECUTED CHRISTIANS There will be an appeal by Aid to the Church in Need on behalf of persecuted Christians in the Middle East at all Sunday Masses on 4th/5th July. PLENARY INDULGENCE FOR THE JUBILEE YEAR OF ST PHILIP NERI In celebration of the 500th anniversary of the birth of our Holy Father St Philip Neri (21st July 1515), Pope Francis has granted a Jubilee Year with an attached Plenary Indulgence, subject to the usual conditions (sacramental Confession, Holy Communion, and prayer for the intentions of the Supreme Pontiff). During the Jubilee Year, which runs from 25th May 2015 to 26 May 2016, the indulgence can be gained every day in our church (and in any other church of a canonically established Congregation of the Oratory). To gain the indulgence, a pilgrimage must be made, or one should take part in a service or devotion in honour of St Philip, concluding by saying the Our Father and Creed and prayers to the Blessed Virgin Mary and St Philip. -

Converts to Rome

C O N V E R T S T O R O M E . A L I S T O F A B O U T FO UR TH O US A N D PR OTE S TA N TS WH O HA V E R E CE N T LY BE C O M E R M A N A T H LI O C O CS . C OM PILE D BY R N G R M A N W. G D O O O , “ ’ O T W LA E DIT IO OM IT S E DIT R O F T H E O S T N S O F R E S R ECR U . S E C O N D E D I T I O JV . LO NDO N W . S W A N S O N N E N S C H E I N A N D C O . , PA T E RNO S TE R S QUA RE . 1 88 5 . PREFA CE T O T HE SE CON D E DIT ION . C O NSIDERING the reception which has been accorded to the “ of C R in new issue onverts to ome, and bearing mind the m of P 1 k it m k few co ments the ress, thin necessary to a e a observations on points which will interest my readers . As r D seve al reviewers , notably those connected with issenting O re I rgans , have been under the imp ssion that have been honoured by the assistance of the Premier in the compilation of k t f my wor , it will be as well to state tha the ollowing e M r G E of letter, writt n by .