Mapping Tourism Pressure in the Sunda-Banda Seascape (Indonesia) MPA Network and Implications for MPA Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Walk on the Wild Side

SCAPES Island Trail your chauffeur; when asked to overtake, he regards you with bewildered incomprehension: “Overtake?” Balinese shiftlessness and cerebral inertia exasperate, particularly the anguished Japanese management with their brisk exactitude at newly-launched Hoshinoya. All that invigorates Bali is the ‘Chinese circus’. Certain resort lobbies, Ricky Utomo of the Bvlgari Resort chuckles, “are like a midnight sale” pulsating with Chinese tourists in voluble haberdashery, high-heeled, almost reeling into lotus ponds they hazard selfies on. The Bvlgari, whose imperious walls and august prices discourage the Chinese, say they had to terminate afternoon tea packages (another Balinese phenomenon) — can’t have Chinese tourists assail their precipiced parapets for selfies. The Chinese wed in Bali. Indians honeymoon there. That said, the isle inspires little romance. In the Viceroy’s gazebo, overlooking Ubud’s verdure, a honeymooning Indian girl, exuding from her décolleté, contuses her anatomy à la Bollywood starlet, but her husband keeps romancing his iPhone while a Chinese man bandies a soft toy to entertain his wife who shuts tight her eyes in disdain as Mum watches on in wonderment. When untoward circumstances remove us to remote and neglected West Bali National Park, where alone on the island you spot deer, two varieties, extraordinarily drinking salt water, we stumble upon Bali’s most enthralling hideaway and meet Bali’s savviest man, general manager Gusti at Plataran Menjangan (an eco-luxury resort in a destination unbothered about -

From the Jungles of Sumatra and the Beaches of Bali to the Surf Breaks of Lombok, Sumba and Sumbawa, Discover the Best of Indonesia

INDONESIAThe Insiders' Guide From the jungles of Sumatra and the beaches of Bali to the surf breaks of Lombok, Sumba and Sumbawa, discover the best of Indonesia. Welcome! Whether you’re searching for secluded surf breaks, mountainous terrain and rainforest hikes, or looking for a cultural surprise, you’ve come to the right place. Indonesia has more than 18,000 islands to discover, more than 250 religions (only six of which are recognised), thousands of adventure activities, as well as fantastic food. Skip the luxury, packaged tours and make your own way around Indonesia with our Insider’s tips. & Overview Contents MALAYSIA KALIMANTAN SULAWESI Kalimantan Sumatra & SUMATRA WEST PAPUA Jakarta Komodo JAVA Bali Lombok Flores EAST TIMOR West Papua West Contents Overview 2 West Papua 23 10 Unique Experiences A Nomad's Story 27 in Indonesia 3 Central Indonesia Where to Stay 5 Java and Central Indonesia 31 Getting Around 7 Java 32 & Java Indonesian Food 9 Bali 34 Cultural Etiquette 1 1 Nusa & Gili Islands 36 Sustainable Travel 13 Lombok 38 Safety and Scams 15 Sulawesi 40 Visa and Vaccinations 17 Flores and Komodo 42 Insurance Tips Sumatra and Kalimantan 18 Essential Insurance Tips 44 Sumatra 19 Our Contributors & Other Guides 47 Kalimantan 21 Need an Insurance Quote? 48 Cover image: Stocksy/Marko Milovanović Stocksy/Marko image: Cover 2 Take a jungle trek in 10 Unique Experiences Gunung Leuser National in Indonesia Park, Sumatra Go to page 20 iStock/rosieyoung27 iStock/South_agency & Overview Contents Kalimantan Sumatra & Hike to the top of Mt. -

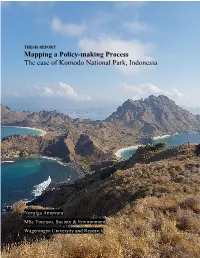

Mapping a Policy-Making Process the Case of Komodo National Park, Indonesia

THESIS REPORT Mapping a Policy-making Process The case of Komodo National Park, Indonesia Novalga Aniswara MSc Tourism, Society & Environment Wageningen University and Research A Master’s thesis Mapping a policy-making process: the case of Komodo National Park, Indonesia Novalga Aniswara 941117015020 Thesis Code: GEO-80436 Supervisor: prof.dr. Edward H. Huijbens Examiner: dr. ir. Martijn Duineveld Wageningen University and Research Department of Environmental Science Cultural Geography Chair Group Master of Science in Tourism, Society and Environment i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Tourism has been an inseparable aspect of my life, starting with having a passion for travelling until I decided to take a big step to study about it back when I was in vocational high school. I would say, learning tourism was one of the best decisions I have ever made in my life considering opportunities and experiences which I encountered on the process. I could recall that four years ago, I was saying to myself that finishing bachelor would be my last academic-related goal in my life. However, today, I know that I was wrong. With the fact that the world and the industry are progressing and I raise my self-awareness that I know nothing, here I am today taking my words back and as I am heading towards the final chapter from one of the most exciting journeys in my life – pursuing a master degree in Wageningen, the Netherlands. Never say never. In completing this thesis, I received countless assistances and helps from people that I would like to mention. Firstly, I would not be at this point in my life without the blessing and prayers from my parents, grandma, and family. -

Hemi Kingi by Brian Sheppard 9 Workshop Reflections by Brian Sheppard 11

WORLD HERITAGE MANAGERS WORKSHOP PROCEEDINGS OF THE WORLD HERITAGE MANAGERS WORKSHOP Tongariro National Park, New Zealand 26–30 October 2000 Contents/Introduction 1 WORLD HERITAGE MANAGERS WORKSHOP Cover: Ngatoroirangi, a tohunga and navigator of the Arawa canoe, depicted rising from the crater to tower over the three sacred mountains of Tongariro National Park—Tongariro (foreground), Ngauruhoe, and Ruapehu (background). Photo montage: Department of Conservation, Turangi This report was prepared for publication by DOC Science Publishing, Science & Research Unit, Science Technology and Information Services, Department of Conservation, Wellington; design and layout by Ian Mackenzie. © Copyright October 2001, New Zealand Department of Conservation ISBN 0–478–22125–8 Published by: DOC Science Publishing, Science & Research Unit Science and Technical Centre Department of Conservation PO Box 10-420 Wellington, New Zealand Email: [email protected] Search our catalogue at http://www.doc.govt.nz 2 World Heritage Managers Workshop—Tongariro, 26–30 October 2000 WORLD HERITAGE MANAGERS WORKSHOP CONTENTS He Kupu Whakataki—Foreword by Tumu Te Heuheu 7 Hemi Kingi by Brian Sheppard 9 Workshop reflections by Brian Sheppard 11 EVALUATING WORLD HERITAGE MANAGEMENT 13 KEYNOTE SPEAKERS Performance management and evaluation 15 Terry Bailey, Projects Manager, Kakadu National Park, NT, Australia Managing our World Heritage 25 Hugh Logan, Director General, Department of Conservation, Wellington, New Zealand Tracking the fate of New Zealand’s natural -

Singapore U Bali U Borneo Java U Borobudur U Komodo

distinguished travel for more than 35 years u u Singapore Bali Borneo Java u Borobudur u Komodo INDONESIA THAILAND a voyage aboard the Bangkok CAMBODIA Kumai BORNEO Exclusively Chartered Siem Reap South Angkor Wat China Sea Five-Star Small Ship Tanjung Puting National Park Java Sea INDONESIA Le Lapérouse SINGAPORE Indian Semarang Ocean BALI MOYO JAVA ISLAND KOMODO Borobudur Badas Temple Prambanan Temple UNESCO World Heritage Site Denpasar Cruise Itinerary BALI Komodo SUMBAWA Air Routing National Park Land Routing September 23 to October 8, 2021 Singapore u Bali u Sumbawa u Semarang Kumai u Moyo Island u Komodo Island xperience the spectacular landscapes, tropical E 1 Depart the U.S. or Canada biodiversity and vast cultural treasures of Indonesia and 2 Cross the International Date Line Singapore on this comprehensive, 16-day journey 3 Arrive in Singapore featuring four nights in Five-Star hotels and an eight-night 4-5 Singapore/Fly to Bali, Indonesia 6 Denpasar, Bali cruise round trip Bali aboard the exclusively chartered, 7 Ubud/Benoa/Embark Le Lapérouse Five-Star Le Lapérouse. Discover Singapore’s compelling 8 Cruising the Java Sea to Java ethnic tableau, Bali’s authentic cultural traditions and 9 Semarang, Java (Borobudur and Prambanan Temples) 10 Cruising the Java Sea to Borneo breathtaking scenery, and the UNESCO-inscribed 11 Kumai, Borneo/Tanjung Puting National Park temples of Borobudur and Prambanan. Embark on a 12 Cruising the Java Sea to Sumbawa river cruise in Borneo to observe the world’s largest 13 Badas, Sumbawa/Moyo Island 14 Komodo Island (Komodo National Park) population of orangutans and visit Komodo Island 15 Denpasar, Bali/Disembark ship/Depart Bali/ to see its fabled dragons. -

Final Report Evaluation Institutional Arrangement and Policies for Multiple-Use Conservation Area and Its Surroundings Managem

FINAL REPORT EVALUATION INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENT AND POLICIES FOR MULTIPLE-USE CONSERVATION AREA AND ITS SURROUNDINGS MANAGEMENT: PILOT APPLICATION FOR THE BUKIT BAKA/BUKIT RAYA AND THE BUNAKEN NATIONAL PARK Jakarta, November 1993 PT INDOCONSULT JAKARTA FOREWORD This is a Final report of "Evaluation Institutional Arrangement and Policies for Multiple. Use Conservation Area and Its Surroundings Management :Pilot Application for The Bukit Baka /Bukit Raya and The Bunaken National Park", composing by Indoconsull Team. This Report forms a Reviewing based on the App,'oach and Methodology proposed ir the Technical Proposal, Field Surveys and Discussions with Counterpart Team frorr the Ministry of Forestry. Our Team consists of : Nature Conservation Speciaiist Ir. M.P.L Tobing Institutional/Social Economy Spec Drs. B.Widaryanto Staf/Surveyor . Drs. Thobby Wakarmamu, MSc Staf/Surveyor . Doddy Ito, SE Project Secretary Yunitasari, SE We hope that this study meets the requirements of MOF and can be in a use of assisting the Development in Forestry sector specifically for the National Park. We are very much appreciate for any assistance given either in a form of information, data or suggestions. Ja a ta, November 1993 Soemarno Soedarsono President Director 'PT. INDOCONSULT-.- CONTENTS BEST AVAILABLE DOCUMENT CONTENTS CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION ............................ I-i 1. Background ................................ I-i 2. Objective and Scope of Study ................ 1-2 a. Study Objectives ...................1-2 b. Scope ............................ 1-3 3. Research Methodology ....................... 1-3 a. Research Approach ..................1-3 b. Research Area ......................1-4 c. Data Collection and Analysis ..... 1-4 4. Framework of Analysis ........................1-5 5. Management and Development ...................1-7 of Conservation Area 1. -

1548037885.Pdf

Time for Change i Time for Change Time for Change The rising sun above the Bromo Tengger Semeru National Park, a symbol of spirit to change and a hope for a better future of environmental and forestry management, a dignified sector that is more beneficial for the community, the nation and the country. ii iii Time for Change Time for Change Preface Dynamic… in the government structure. She began For instance, the provision of wider access The readiness of local governments and economic growth, while maintaining future. The problems encountered her work with a simple yet precise step, to forest resources for local community their field staff to prevent and suppress biodiversity and its ecosystem in during 2014-2019 were too huge and It reflects the milestones of environment conducted dialogues with all parties and which led to an increase of 5.4 million forest and land fires became a priority to particular. too complex, therefore not all activities and forestry sectors during the period absorbing every single aspiration. She hectares of accessible forest areas to be be addressed and improved. Siti Nurbaya conducted can be presented in an intact 2014-2019, under the leadership of met and talked with many parties: high utilized by the community for generating succeeded in reducing the area of forest Furthermore, under the leadership way in this book. President Joko Widodo (Jokowi). The level officials and former ministers in the incomes. In terms of the percentage, the fires from 2.6 million hectares recorded of Siti Nurbaya, MoEF played an dynamics started when the President two ministries, forestry and environmental forests management permits granted to in 2015, to 438,363 hectares (in 2016), important role in international arenas. -

Bali to Bali

STAR CLIPPERS SHORE EXCURSIONS Bali – Bali itineraries West bound: Benoa (Bali) - Giligenteng (Madura) – Probolinggo (Java) – Lovina Beach (Bali) – Senggigi beach (Lombok) – Gili Sudak (Lombok, Nusa Tenggara) – Benoa (Bali) East bound: Benoa (Bali) - Gili Kondo (Lombok) – Komodo National Park, Pink beach – Satonda – Gili Meno/Gili Trawangan (Lombok) – Gili Nanggu (Lombok) – Benoa (Bali) We use the best available guides and transportation for all our tours. However since your cruise will take you to many exotic destinations off the usual tourist radar, you must be prepared to encounter minor inconveniences and infrastructure which is not always of the highest standard: restaurant services may be rather basic, toilet facilities can be quite primitive by Western standards and tour guides will not be as sophisticated as those found in the Mediterranean. Nevertheless we are confident that these drawbacks will be far outweighed by the truly unique and unforgettable experiences you will take home with you. All tours are offered with English speaking guides. The length of the tours as well as the time spent on the various sites, is given as an indication only as it may vary depending on the road, weather, sea and traffic conditions and the group’s pace. STAR CLIPPERS SHORE EXCURSIONS With the exception of Bali, Indonesia is a country with a very strong muslim tradition ; certain excursions may be modified or even cancelled depending on religious festivals Fitness requirements vary according to your chosen activity. If you would like to participate in hiking, snorkeling and boating, an average to good level of fitness is mandatory. Please note that the activity level of our excursions is given as a guideline, much depends on your own personal fitness. -

Member's Report on Activities Related to ICRI

Member’s Report ICRI GM 29 – Indonesia INTERNATIONAL CORAL REEF INITIATIVE (ICRI) 29th General Meeting 20-23 October 2014 – Okinawa, Japan Member’s report on activities related to ICRI Reporting period October 2013 – September 2014 1. Updates on your activities. Project 1 Cornerstone(s) Check all that apply: implemented through Integrated Management Capacity Building the project Science & Monitoring Periodic Assessment (Review) Project Title Community Behavior Change (Pride) Campaign for Sustainable Fisheries in Tomia , Wakatobi National Park, Location Conservation Section III Tomia, Wakatobi National Park, Indonesia Project Duration: May 2012 – July 2014 Dates Campaign Duration: June 2013 – May 2014 RARE (www.rare.org) Main Organizer(s) Wakatobi National Park Office All community in Tomia Island, particularly Tomia Fishermen Main Stakeholder(s) Community (Komunitas Nelayan Tomia – KOMUNTO), Ranger Partner Community (Masyarakat Mitra Polhut – MMP) in West Waitii Village, Waitii Village, and Lamanggau Village Rare is committed to work with its partners to support sustainable behaviour change for ecosystem conservation. This effort also contributes to the sustainability of the lives of community around area with high biodiversity values. Rare provided training, coaching, and mentorship to local organizations on social marketing method and communication skills. This program is known as Pride Campaign Program to support local communities build the pride for the uniqueness of the biodiversity around them and take real action to protect ecosystem. Social Description of Project marketing approach in Pride Program uses various communication (Please elaborate on channel used by commercial marketing to touch the heart and mind of how the project the target audience and encourage behaviour change to achieve implements the FFA conservation impact. -

Wildlife-Animal Tourism Development and Lessons from Indonesia

69 C-02 WILDLIFE-ANIMAL TOURISM DEVELOPMENT AND LESSONS FROM INDONESIA Budi Guntoro1 1Faculty of Animal Science, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Jl. Fauna 3, Yogyakarta, Indonesia 55281 (E-mail: [email protected]) Introduction Wildlife-animal tourism encompasses a range of activities, including bird watching, wildlife viewing, photographic and walking safaris, reef diving, whale watching, trophy hunting and sport fishing. Wildlife tourism may be achieved through many different forms of transport, including on foot, by vehicle, boat or balloon. Wildlife tourism may be purposeful or may also include tourists who visit wildlife areas as an incidental part of a broader trip. Business trips may also involve visits to wildlife areas that are casual diversions rather than the prime motivation for visiting a country. Wildlife tourism is an important component of the international and domestic tourism industry. Overall, depending on the region, wildlife tourism accounts for 20 to 40 per cent of international tourism (Filion et al.1992; Giongo et al.1993, CEP 1994). The scale of wildlife tourism is even larger if domestic wildlife tourism is taken into consideration. However, statistics are often not available to determine what proportion of wildlife tourism is domestic in origin, but it is likely to be very high in some countries. As with tourism generally, wildlife tourism is likely to increase in importance and scale (Giongo et al. 1993). Furthermore, it may also attract an increasing market share, as suggested by a number of surveys indicating an increasing interest in wildlife among tourists. The last 20 years have seen a shift in favoured tourism destinations towards developing countries, especially those rich in biodiversity. -

Tourism Development and Local Livelihoods in Komodo District, East Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia

The Double-edged Sword of Tourism: Tourism Development and Local Livelihoods in Komodo District, East Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia Author Lasso, Aldi Herindra Published 2017-05-02 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School Dept Intnl Bus&Asian Studies DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/949 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/370982 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au The Double-edged Sword of Tourism: Tourism Development and Local Livelihoods in Komodo District, East Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia by Mr Aldi Herindra LASSO Master of Tourism Management, Bandung Institute of Tourism, Indonesia Department of International Business and Asian Studies Griffith Business School Griffith University Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2 May 2017 ABSTRACT Tourism development has long been promoted as an effective means of bringing improvements to local communities. However, along with many positive benefits of tourism there are many negative impacts on economic, social and environmental aspects of communities. The introduction of tourism often triggers alterations in the way local people make a living. Such alterations often lead to full tourism-dependent livelihoods, affecting the sustainability of traditional livelihoods due to the unreliability of the tourism industry. This study provides empirical evidence of such alterations in local communities. The research data for this study was collected in Komodo District, West Manggarai, East Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia, with the souvenir, tour boat and travel businesses as case studies. Using qualitative methods, this study elaborates the impacts of tourism on local livelihoods, by focusing on: the process of how tourism affected local livelihoods; the opportunities and threats emerging from the impact of tourism; the strategies applied to respond to the challenges; and the locals’ perspectives of influential stakeholders and sustainable tourism development. -

Indonesia 12

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Indonesia Sumatra Kalimantan p509 p606 Sulawesi Maluku p659 p420 Papua p464 Java p58 Nusa Tenggara p320 Bali p212 David Eimer, Paul Harding, Ashley Harrell, Trent Holden, Mark Johanson, MaSovaida Morgan, Jenny Walker, Ray Bartlett, Loren Bell, Jade Bremner, Stuart Butler, Sofia Levin, Virginia Maxwell PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to Indonesia . 6 JAVA . 58 Malang . 184 Indonesia Map . 8 Jakarta . 62 Around Malang . 189 Purwodadi . 190 Indonesia’s Top 20 . 10 Thousand Islands . 85 West Java . 86 Gunung Arjuna-Lalijiwo Need to Know . 20 Reserve . 190 Banten . 86 Gunung Penanggungan . 191 First Time Indonesia . 22 Merak . 88 Batu . 191 What’s New . 24 Carita . 88 South-Coast Beaches . 192 Labuan . 89 If You Like . 25 Blitar . 193 Ujung Kulon Month by Month . 27 National Park . 89 Panataran . 193 Pacitan . 194 Itineraries . 30 Bogor . 91 Around Bogor . 95 Watu Karang . 195 Outdoor Adventures . 36 Cimaja . 96 Probolinggo . 195 Travel with Children . 52 Cibodas . 97 Gunung Bromo & Bromo-Tengger-Semeru Regions at a Glance . 55 Gede Pangrango National Park . 197 National Park . 97 Bondowoso . 201 Cianjur . 98 Ijen Plateau . 201 Bandung . 99 VANY BRANDS/SHUTTERSTOCK © BRANDS/SHUTTERSTOCK VANY Kalibaru . 204 North of Bandung . 105 Jember . 205 Ciwidey & Around . 105 Meru Betiri Bandung to National Park . 205 Pangandaran . 107 Alas Purwo Pangandaran . 108 National Park . 206 Around Pangandaran . 113 Banyuwangi . 209 Central Java . 115 Baluran National Park . 210 Wonosobo . 117 Dieng Plateau . 118 BALI . 212 Borobudur . 120 BARONG DANCE (P275), Kuta & Southwest BALI Yogyakarta . 124 Beaches . 222 South Coast . 142 Kuta & Legian . 222 Kaliurang & Kaliadem . 144 Seminyak .