Resource Utilization in and Around Komodo National Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Walk on the Wild Side

SCAPES Island Trail your chauffeur; when asked to overtake, he regards you with bewildered incomprehension: “Overtake?” Balinese shiftlessness and cerebral inertia exasperate, particularly the anguished Japanese management with their brisk exactitude at newly-launched Hoshinoya. All that invigorates Bali is the ‘Chinese circus’. Certain resort lobbies, Ricky Utomo of the Bvlgari Resort chuckles, “are like a midnight sale” pulsating with Chinese tourists in voluble haberdashery, high-heeled, almost reeling into lotus ponds they hazard selfies on. The Bvlgari, whose imperious walls and august prices discourage the Chinese, say they had to terminate afternoon tea packages (another Balinese phenomenon) — can’t have Chinese tourists assail their precipiced parapets for selfies. The Chinese wed in Bali. Indians honeymoon there. That said, the isle inspires little romance. In the Viceroy’s gazebo, overlooking Ubud’s verdure, a honeymooning Indian girl, exuding from her décolleté, contuses her anatomy à la Bollywood starlet, but her husband keeps romancing his iPhone while a Chinese man bandies a soft toy to entertain his wife who shuts tight her eyes in disdain as Mum watches on in wonderment. When untoward circumstances remove us to remote and neglected West Bali National Park, where alone on the island you spot deer, two varieties, extraordinarily drinking salt water, we stumble upon Bali’s most enthralling hideaway and meet Bali’s savviest man, general manager Gusti at Plataran Menjangan (an eco-luxury resort in a destination unbothered about -

From the Jungles of Sumatra and the Beaches of Bali to the Surf Breaks of Lombok, Sumba and Sumbawa, Discover the Best of Indonesia

INDONESIAThe Insiders' Guide From the jungles of Sumatra and the beaches of Bali to the surf breaks of Lombok, Sumba and Sumbawa, discover the best of Indonesia. Welcome! Whether you’re searching for secluded surf breaks, mountainous terrain and rainforest hikes, or looking for a cultural surprise, you’ve come to the right place. Indonesia has more than 18,000 islands to discover, more than 250 religions (only six of which are recognised), thousands of adventure activities, as well as fantastic food. Skip the luxury, packaged tours and make your own way around Indonesia with our Insider’s tips. & Overview Contents MALAYSIA KALIMANTAN SULAWESI Kalimantan Sumatra & SUMATRA WEST PAPUA Jakarta Komodo JAVA Bali Lombok Flores EAST TIMOR West Papua West Contents Overview 2 West Papua 23 10 Unique Experiences A Nomad's Story 27 in Indonesia 3 Central Indonesia Where to Stay 5 Java and Central Indonesia 31 Getting Around 7 Java 32 & Java Indonesian Food 9 Bali 34 Cultural Etiquette 1 1 Nusa & Gili Islands 36 Sustainable Travel 13 Lombok 38 Safety and Scams 15 Sulawesi 40 Visa and Vaccinations 17 Flores and Komodo 42 Insurance Tips Sumatra and Kalimantan 18 Essential Insurance Tips 44 Sumatra 19 Our Contributors & Other Guides 47 Kalimantan 21 Need an Insurance Quote? 48 Cover image: Stocksy/Marko Milovanović Stocksy/Marko image: Cover 2 Take a jungle trek in 10 Unique Experiences Gunung Leuser National in Indonesia Park, Sumatra Go to page 20 iStock/rosieyoung27 iStock/South_agency & Overview Contents Kalimantan Sumatra & Hike to the top of Mt. -

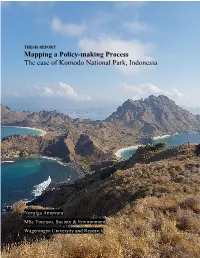

Mapping a Policy-Making Process the Case of Komodo National Park, Indonesia

THESIS REPORT Mapping a Policy-making Process The case of Komodo National Park, Indonesia Novalga Aniswara MSc Tourism, Society & Environment Wageningen University and Research A Master’s thesis Mapping a policy-making process: the case of Komodo National Park, Indonesia Novalga Aniswara 941117015020 Thesis Code: GEO-80436 Supervisor: prof.dr. Edward H. Huijbens Examiner: dr. ir. Martijn Duineveld Wageningen University and Research Department of Environmental Science Cultural Geography Chair Group Master of Science in Tourism, Society and Environment i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Tourism has been an inseparable aspect of my life, starting with having a passion for travelling until I decided to take a big step to study about it back when I was in vocational high school. I would say, learning tourism was one of the best decisions I have ever made in my life considering opportunities and experiences which I encountered on the process. I could recall that four years ago, I was saying to myself that finishing bachelor would be my last academic-related goal in my life. However, today, I know that I was wrong. With the fact that the world and the industry are progressing and I raise my self-awareness that I know nothing, here I am today taking my words back and as I am heading towards the final chapter from one of the most exciting journeys in my life – pursuing a master degree in Wageningen, the Netherlands. Never say never. In completing this thesis, I received countless assistances and helps from people that I would like to mention. Firstly, I would not be at this point in my life without the blessing and prayers from my parents, grandma, and family. -

Hemi Kingi by Brian Sheppard 9 Workshop Reflections by Brian Sheppard 11

WORLD HERITAGE MANAGERS WORKSHOP PROCEEDINGS OF THE WORLD HERITAGE MANAGERS WORKSHOP Tongariro National Park, New Zealand 26–30 October 2000 Contents/Introduction 1 WORLD HERITAGE MANAGERS WORKSHOP Cover: Ngatoroirangi, a tohunga and navigator of the Arawa canoe, depicted rising from the crater to tower over the three sacred mountains of Tongariro National Park—Tongariro (foreground), Ngauruhoe, and Ruapehu (background). Photo montage: Department of Conservation, Turangi This report was prepared for publication by DOC Science Publishing, Science & Research Unit, Science Technology and Information Services, Department of Conservation, Wellington; design and layout by Ian Mackenzie. © Copyright October 2001, New Zealand Department of Conservation ISBN 0–478–22125–8 Published by: DOC Science Publishing, Science & Research Unit Science and Technical Centre Department of Conservation PO Box 10-420 Wellington, New Zealand Email: [email protected] Search our catalogue at http://www.doc.govt.nz 2 World Heritage Managers Workshop—Tongariro, 26–30 October 2000 WORLD HERITAGE MANAGERS WORKSHOP CONTENTS He Kupu Whakataki—Foreword by Tumu Te Heuheu 7 Hemi Kingi by Brian Sheppard 9 Workshop reflections by Brian Sheppard 11 EVALUATING WORLD HERITAGE MANAGEMENT 13 KEYNOTE SPEAKERS Performance management and evaluation 15 Terry Bailey, Projects Manager, Kakadu National Park, NT, Australia Managing our World Heritage 25 Hugh Logan, Director General, Department of Conservation, Wellington, New Zealand Tracking the fate of New Zealand’s natural -

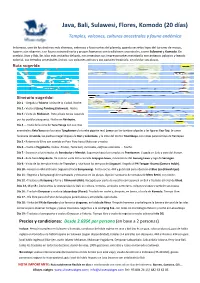

Java, Bali, Sulawesi, Flores, Komodo (20 Días)

Java, Bali, Sulawesi, Flores, Komodo (20 días) Templo s, volcanes, culturas ancestral es y fauna endémica Indonesia, uno de los destinos más diversos, extensos y fascinantes del planeta, guarda secretos lejos del turismo de masas, lugares aún vírgenes, con fauna extraordinaria y grupos humanos con tradiciones ancestrales, como Sulawesi y Komodo . En cambio, Java y Bali, la s islas más visitadas del país, nos muestran sus impresionantes metrópolis con antiguos palacios y legado colonial, sus templos ancestrales únicos, sus volcanes activos y sus paisajes tropicials, sin olvidar sus playas. Ruta sugerida Itinerario sugerido: Día 1 .- Llegada a Yakarta i visita de la ciudad. Noche. Día 2.- Vuelo a Ujung Pandang (Sulawesi). Noche. Dia 3.- Visita de Makassar. Ruta al pais toraja pasando por los pueblos pesqueros. Noche en Rantepao. Día 4 .-. Visita de la zona de Tana Toraja con sus ritos ancestrales: Kete'kesu con las casas Tongkonan y la tumba gigante real, Lemo con las tumbas colgadas y las figuras Tau-Tau , la cueva funeraria de Londa , las piedras megal.lítiques de Bori y Lokomata , y la cima del monte Tinombayo , con vistas panorámicas de Rantepao. Día 5.- Retorno de 8 hrs con comida en Pare-Par e hasta Makassar y noche.. Día 6 .- Vuelo a Yogjakarta . Visitas: Kraton, Tama Sari, mercados, edificios coloniales ... Noche. Día 7.- Excursión a los templos de Borobudur y Mendut. Seguimos hacia los templos de Prambanan . Llegada en Solo y vista de l Kraton . Día 8.- Ruta hacia Mojokerto . De camino visita de la cascada Grojogan Sewu , monasterios del Gunung Lawu y lago de Sarangan . -

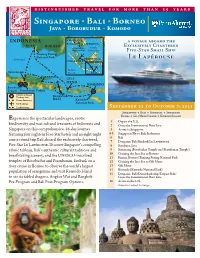

Singapore U Bali U Borneo Java U Borobudur U Komodo

distinguished travel for more than 35 years u u Singapore Bali Borneo Java u Borobudur u Komodo INDONESIA THAILAND a voyage aboard the Bangkok CAMBODIA Kumai BORNEO Exclusively Chartered Siem Reap South Angkor Wat China Sea Five-Star Small Ship Tanjung Puting National Park Java Sea INDONESIA Le Lapérouse SINGAPORE Indian Semarang Ocean BALI MOYO JAVA ISLAND KOMODO Borobudur Badas Temple Prambanan Temple UNESCO World Heritage Site Denpasar Cruise Itinerary BALI Komodo SUMBAWA Air Routing National Park Land Routing September 23 to October 8, 2021 Singapore u Bali u Sumbawa u Semarang Kumai u Moyo Island u Komodo Island xperience the spectacular landscapes, tropical E 1 Depart the U.S. or Canada biodiversity and vast cultural treasures of Indonesia and 2 Cross the International Date Line Singapore on this comprehensive, 16-day journey 3 Arrive in Singapore featuring four nights in Five-Star hotels and an eight-night 4-5 Singapore/Fly to Bali, Indonesia 6 Denpasar, Bali cruise round trip Bali aboard the exclusively chartered, 7 Ubud/Benoa/Embark Le Lapérouse Five-Star Le Lapérouse. Discover Singapore’s compelling 8 Cruising the Java Sea to Java ethnic tableau, Bali’s authentic cultural traditions and 9 Semarang, Java (Borobudur and Prambanan Temples) 10 Cruising the Java Sea to Borneo breathtaking scenery, and the UNESCO-inscribed 11 Kumai, Borneo/Tanjung Puting National Park temples of Borobudur and Prambanan. Embark on a 12 Cruising the Java Sea to Sumbawa river cruise in Borneo to observe the world’s largest 13 Badas, Sumbawa/Moyo Island 14 Komodo Island (Komodo National Park) population of orangutans and visit Komodo Island 15 Denpasar, Bali/Disembark ship/Depart Bali/ to see its fabled dragons. -

Southeast-Asia-On-A-Shoestring-17-Contents.Pdf

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Southeast Asia on a shoestring Myanmar (Burma) p480 Laos p311 Thailand Vietnam p643 p812 Cambodia Philippines p64 p547 Brunei Darussalam p50 Malaysia p378 Singapore p613 Indonesia Timor- p149 Leste p791 THIS EDITION WRITTEN AND RESEARCHED BY China Williams, Greg Bloom, Celeste Brash, Stuart Butler, Shawn Low, Simon Richmond, Daniel Robinson, Iain Stewart, Ryan Ver Berkmoes, Richard Waters PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to BRUNEI Batu .Karas. 169 Southeast Asia . .6 DARUSSALAM . 50 Wonosobo. 170 Southeast Asia Map . .8 Bandar Seri Begawan . 53 Dieng .Plateau. 170 Southeast Asia’s Top 20 . .10 Jerudong. 58 Yogyakarta. 171. Muara. 59 Prambanan. 179 Need to Know . 20 Temburong.District. 59 Borobudur. 179 First Time Understand Brunei Solo .(Surakarta). 182 Southeast Asia . 22 Darussalam . 60 Malang .&.Around. 185 If You Like… . 24 Survival Guide . 61 Gunung .Bromo. 187 Month by Month . 26 CAMBODIA . 64 Bondowoso. 190 Ijen .Plateau. 190 Itineraries . 30 Phnom Penh . 68 Banyuwangi. 191 Off the Beaten Track . 36 Siem Reap & the Temples of Angkor . 85 Bali . .191 Big Adventures, Siem .Reap. 86 Kuta, .Legian,.Seminyak.. Small Budget . 38 & .Kerabokan. 195 Templesf .o .Angkor. 94 Canggu .Area. .202 Countries at a Glance . 46 Northwestern Cambodia . 103 Bukit .Peninsula .. .. .. .. .. .. ...202 Battambang.. 103 Denpasar. .204 117 IMAGERY/GETTY IMAGES © Prasat .Preah.Vihear.. 108 Sanur. .206 Kompong .Thom.. 110 Nusa .Lembongan. 207 South Coast . 111 Ubud. .208 Koh .Kong.City.. .111 East .Coast.Beaches. 215 Koh .Kong.. Semarapura.(Klungkung). 215. Conservation.Corridor . 114 Sidemen .Road . 215 Sihanoukville.. 114 Padangbai. 215 The .Southern.Islands . 121 Candidasa. 216 Kampot.. 122 Tirta .Gangga. -

Final Report Evaluation Institutional Arrangement and Policies for Multiple-Use Conservation Area and Its Surroundings Managem

FINAL REPORT EVALUATION INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENT AND POLICIES FOR MULTIPLE-USE CONSERVATION AREA AND ITS SURROUNDINGS MANAGEMENT: PILOT APPLICATION FOR THE BUKIT BAKA/BUKIT RAYA AND THE BUNAKEN NATIONAL PARK Jakarta, November 1993 PT INDOCONSULT JAKARTA FOREWORD This is a Final report of "Evaluation Institutional Arrangement and Policies for Multiple. Use Conservation Area and Its Surroundings Management :Pilot Application for The Bukit Baka /Bukit Raya and The Bunaken National Park", composing by Indoconsull Team. This Report forms a Reviewing based on the App,'oach and Methodology proposed ir the Technical Proposal, Field Surveys and Discussions with Counterpart Team frorr the Ministry of Forestry. Our Team consists of : Nature Conservation Speciaiist Ir. M.P.L Tobing Institutional/Social Economy Spec Drs. B.Widaryanto Staf/Surveyor . Drs. Thobby Wakarmamu, MSc Staf/Surveyor . Doddy Ito, SE Project Secretary Yunitasari, SE We hope that this study meets the requirements of MOF and can be in a use of assisting the Development in Forestry sector specifically for the National Park. We are very much appreciate for any assistance given either in a form of information, data or suggestions. Ja a ta, November 1993 Soemarno Soedarsono President Director 'PT. INDOCONSULT-.- CONTENTS BEST AVAILABLE DOCUMENT CONTENTS CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION ............................ I-i 1. Background ................................ I-i 2. Objective and Scope of Study ................ 1-2 a. Study Objectives ...................1-2 b. Scope ............................ 1-3 3. Research Methodology ....................... 1-3 a. Research Approach ..................1-3 b. Research Area ......................1-4 c. Data Collection and Analysis ..... 1-4 4. Framework of Analysis ........................1-5 5. Management and Development ...................1-7 of Conservation Area 1. -

Publikasi Jurnal (8).Pdf

KERAGAMAN HAYATI DALAM RELIEF CANDI SEBAGAI BENTUK KONSERVASI LINGKUNGAN (Studi Kasus di Candi Penataran Kabupaten Blitar) Dra. Theresia Widiastuti, M.Sn. [email protected] Dr. Supana, M.Hum. [email protected] Drs. Djoko Panuwun, M.Sn. [email protected] Abstrak Tujuan jangka panjang penelitian ini adalah mengangkat eksistensi Candi Penataran, tidak saja sebagai situs religi, namun sebagai sumber pengetahuan kehidupan (alam, lingkungan, sosial, dan budaya). Tujuan khusus penelitian ini adalah melakukan dokumentasi dan inventarisasi berbagai bentuk keragaman hayati, baik flora maupun fauna, yang terdapat dalam relief Candi Penataran. Temuan dalam penelitian ini berupa informasi yang lengkap, cermat, dan sahih mengenai dokumentasi keragaman hayati dalam relief candi Penataran di Kabupaten Blitar Jawa Timur, klasifikasi keragaman hayati, dan ancangan tafsir yang dapat dugunakan bagi penelitian lain mengenai keragaman hayati, dan penelitian sosial, seni, budaya, pada umumnya. Kata Kunci: Candi, penataran, relief, ragam hias, hayati 1. Latar Belakang Masalah Citra budaya timur, khususnya budaya Jawa, telah dikenal di seluruh penjuru dunia sebagai budaya tinggi dan adi luhung. Hal ini sejalan dengan pendapat Sugiyarto (2011:250) yang menyatakan bahwa Jawa merupakan pusat peradaban karena masyarakat Jawa dikenal sebagai masyarakat yang mampu menyelaraskan diri dengan alam. Terbukti dengan banyaknya peninggalan-peninggalan warisan budaya dari leluhur Jawa, misalnya peninggalan benda-benda purbakala berupa candi. Peninggalan-peninggalan purbakala yang tersebar di wilayah Jawa memberikan gambaran yang nyata betapa kayanya warisan budaya Jawa yang harus digali dan dijaga keberadaannya. Candi Penataran, merupakan simbol axis mundy atau sumber pusat spiritual dan replika penataan pemerintahan kerajaan-kerajaan di Jawa Timur. Banyak penelitian yang telah dilakukan terhadap Candi Penataran, tetapi lebih menyoroti pada tafsir-tafsir historis istana sentris. -

1548037885.Pdf

Time for Change i Time for Change Time for Change The rising sun above the Bromo Tengger Semeru National Park, a symbol of spirit to change and a hope for a better future of environmental and forestry management, a dignified sector that is more beneficial for the community, the nation and the country. ii iii Time for Change Time for Change Preface Dynamic… in the government structure. She began For instance, the provision of wider access The readiness of local governments and economic growth, while maintaining future. The problems encountered her work with a simple yet precise step, to forest resources for local community their field staff to prevent and suppress biodiversity and its ecosystem in during 2014-2019 were too huge and It reflects the milestones of environment conducted dialogues with all parties and which led to an increase of 5.4 million forest and land fires became a priority to particular. too complex, therefore not all activities and forestry sectors during the period absorbing every single aspiration. She hectares of accessible forest areas to be be addressed and improved. Siti Nurbaya conducted can be presented in an intact 2014-2019, under the leadership of met and talked with many parties: high utilized by the community for generating succeeded in reducing the area of forest Furthermore, under the leadership way in this book. President Joko Widodo (Jokowi). The level officials and former ministers in the incomes. In terms of the percentage, the fires from 2.6 million hectares recorded of Siti Nurbaya, MoEF played an dynamics started when the President two ministries, forestry and environmental forests management permits granted to in 2015, to 438,363 hectares (in 2016), important role in international arenas. -

The Genesis of Touristic Imagery in out of the Way Locales, Where Tourism Is Embryonic at Best, Has Yet to Be Examined

TOU54378 Adams 20/4/05 9:12 am Page 115 article ts The genesis of touristic tourist studies © 2004 sage publications imagery London, Thousand Oaks and Politics and poetics in the creation New Delhi vol 4(2) 115–135 1 DOI: 10.1177/ of a remote Indonesian island destination 1468797604054378 www.sagepublications.com Kathleen M. Adams Loyola University Chicago, USA abstract Although the construction and amplification of touristically-celebrated peoples’ Otherness on global mediascapes has been well documented, the genesis of touristic imagery in out of the way locales, where tourism is embryonic at best, has yet to be examined. This article explores the emergent construction of touristic imagery on the small, sporadically visited Eastern Indonesian island of Alor during the 1990s. In examining the ways in which competing images of Alorese people are sculpted by both insiders and outsiders, this article illustrates the politics and power dynamics embedded in the genesis of touristic imagery. Ultimately, I argue that even in remote locales where tourism is barely incipient, ideas and fantasies about tourism can color local politics, flavor discussions of identity and channel local actions. keywords Alor anthropologists and tourism Indonesia politics of tourism touristic imagery Numerous studies have chronicled the ways in which tourism projects have cre- ated exoticized, appealing, or sexualized images of ethnic Others (cf.Aitchison, 2001; Albers and James, 1983; Cohen, 1993, 1995, 1999; Dann, 1996; Deutschlander, 2003; Enloe, 1989; Selwyn, 1993, 1996). Such representations and images form the cornerstone of the cultural tourism industry.Disseminated via travel brochures, web pages, postcards, televised travel programs, and guide books,First these print and photographic imagesProof construct ‘mythic’ Others for touristic consumption (Selwyn, 1996). -

Singapore U Bali U Borneo Java U Borobudur U Komodo

distinguished travel for more than 35 years u u Singapore Bali Borneo Java u Borobudur u Komodo INDONESIA THAILAND a voyage aboard the Bangkok CAMBODIA Kumai BORNEO Exclusively Chartered Siem Reap South Angkor Wat China Sea Five-Star Small Ship Tanjung Puting National Park Java Sea INDONESIA Le Lapérouse SINGAPORE Indian Semarang Ocean BALI Surabaya GILI MENO JAVA KOMODO Borobudur Temple Prambanan Temple UNESCO World Heritage Site Denpasar Cruise Itinerary BALI Komodo Air Routing National Park Land Routing September 22 to October 7, 2021 Singapore u Bali u Surabaya u Semarang Kumai u Gili Meno Island u Komodo Island xperience the spectacular landscapes, exotic E 1 Depart the U.S. biodiversity and vast cultural treasures of Indonesia and 2 Cross the International Date Line Singapore on this comprehensive, 16-day journey 3 Arrive in Singapore featuring four nights in Five-Star hotels and an eight-night 4-5 Singapore/Fly to Bali, Indonesia 6 Bali cruise round trip Bali aboard the exclusively chartered, 7 Denpasar, Bali/Embark Le Lapérouse Five-Star Le Lapérouse. Discover Singapore’s compelling 8 Surabaya, Java ethnic tableau, Bali’s authentic cultural traditions and 9 Semarang (Borobudur Temple and Prambanan Temple) 10 Cruising the Java Sea to Borneo breathtaking scenery, and the UNESCO-inscribed 11 Kumai, Borneo/Tanjung Puting National Park temples of Borobudur and Prambanan. Embark on a 12 Cruising the Java Sea to Gili Meno river cruise in Borneo to observe the world’s largest 13 Gili Meno 14 Komodo (Komodo National Park) population of orangutans and visit Komodo Island 15 Denpasar, Bali/Disembark ship/Depart Bali/ to see its fabled dragons.