A Postmodern Neo-Marxist's Guide to Free Speech: on Jordan Peterson and the ‘Alt-Right’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cr24-Mishra.Pdf

The Cairo Review Interview The Modernity Trap Indian writer Pankaj Mishra probes imperialism’s legacy, liberalism’s failure, and the spreading global disorder lately the rise of the political right has turned some of the coolest heads into the gloomiest of prophets. Indian novelist and essayist Pankaj Mishra takes the long view. his new book, Age of Anger: A History of the Present, traces violent discontent with our modern world from the European Romantics to the Islamic State’s rule of terror. Mishra argues that the persistent fail- ure of modern society to deliver on its promises—freedom, wealth, and equality—has again and again encouraged hateful and militant politics, from messianic revolutionaries in Tsarist Russia to the cultural nationalism of Germany’s nazi era. As Mishra sees it, technology and the pursuit of wealth have shattered traditional societies across the globe, setting adrift mil- lions of people who are “uprooted from tradition but far from modernity.” For Mishra’s withering critiques of imperialism, the Economist called him the “heir to Edward Said.” Mishra’s book From the Ruins of Empire: The Revolt Against the West and the Remaking of Asia declared Asia’s political awakening the twentieth century’s central event, and rebuked the notion that the West offers a benign one-size-fits-all model for modernity. Raised in Jhansi, in Uttar Pradesh, Mishra, 47, started as a travel writer documenting the quiet changes in India’s small towns wrought by economic and technological growth. his first book, Butter Chicken in Ludhiana: Travels in Small Town India, was a hilarious portrait of India’s upwardly mobile classes in the era of globalization. -

Exploring Social Responsibility and Ways of Attracting Greater Readership: an Eclectic Approach to Pankaj Mishra's Selected Wo

2012 International Conference on Language, Medias and Culture IPEDR vol.33 (2012) © (2012) IACSIT Press, Singapore Exploring Social Responsibility and Ways of Attracting Greater Readership: An Eclectic Approach to Pankaj Mishra’s Selected Works + Mohsen Masoomi 1 1 Department of English, Sanandaj Branch, Islamic Azad University, Sanandaj, Iran Abstract. This study reads the selected works of the Indian writer, Pankaj Mishra, in the light of an eclectic approach which aims to explore his social responsibility through his works and also to make a survey on his implementation of certain tools for expanding his readers. The central argument the present study seeks to demonstrate is that, by rendering factual evocations of people through real figures and their social voice, Pankaj Mishra tries to reply an inner call of social responsibility toward Indian community. It is through mediums of mass media, literary institutions, English language and translation that Mishra attains a marked level of readership globally. Two major works of Mishra considered for this research are the mixture of memoir, history, and philosophy, An End to Suffering: The Buddha in the World, and the travel book Temptations of the West: How to be Modern in India, Pakistan and Beyond. Keywords: Pankaj Mishra, eclectic approach, social responsibility, attracting greater readership 1. Introduction After India’s Independence in 1947 and fundamental changes occurring in the country's structural foundations, a new capacity was created for a different trend of literary creation. Indian writers inclined towards a different type of literature that could best depict their new status as partly detached from their colonial past. -

Mediatized Populisms: Inter-Asian Lineages

International Journal of Communication 11(2017), 4073–4092 1932–8036/20170005 Mediatized Populisms: Inter-Asian Lineages Introduction PAULA CHAKRAVARTTY New York University, USA SRIRUPA ROY University of Göttingen, Germany1 This essay offers an explanation for the rise of contemporary “mediatized populisms.” Disaggregating the idea of a singular media logic of populist politics, we examine the institutional and political-economic dynamics of mediatization and the variegated structures of mediated political fields in which contemporary populist political formations are embedded. Moving away from broad “global populism” approaches as well as case studies from Europe and the Americas that have thus far dominated discussions of populism, we make the case for empirically grounded comparative studies of populism from the particular standpoint of regional contexts across Asia that offer theoretical insights often missed in prevailing “technology-first” and election-focused approaches. We then outline three distinctive features of media-politics relations (and their transformations) that have enabled the contemporary rise of mediatized populism across the Inter-Asian region. Keywords: populism, mediatization, Inter-Asian, comparative politics, political economy Paula Chakravartty: [email protected] Srirupa Roy: [email protected] Date submitted: 2017–08–31 1 Research for this essay is funded by the Social Science Research Council of New York’s Transregional Virtual Research Institute on Media Activism and the New Political. Most of the essays in this Special Section were presented at a Social Science Research Council (SSRC) InterAsia workshop on Mediatized Populism Across InterAsia, which was held in Seoul in April 2016. We are grateful to Seteney Shami and Holly Danzeisen of the SSRC, and to all our participants and especially our workshop co-organizer, Zeynep Gambetti, for their deep and constructive engagements and insights. -

The Ramayana by R.K. Narayan

Table of Contents About the Author Title Page Copyright Page Introduction Dedication Chapter 1 - RAMA’S INITIATION Chapter 2 - THE WEDDING Chapter 3 - TWO PROMISES REVIVED Chapter 4 - ENCOUNTERS IN EXILE Chapter 5 - THE GRAND TORMENTOR Chapter 6 - VALI Chapter 7 - WHEN THE RAINS CEASE Chapter 8 - MEMENTO FROM RAMA Chapter 9 - RAVANA IN COUNCIL Chapter 10 - ACROSS THE OCEAN Chapter 11 - THE SIEGE OF LANKA Chapter 12 - RAMA AND RAVANA IN BATTLE Chapter 13 - INTERLUDE Chapter 14 - THE CORONATION Epilogue Glossary THE RAMAYANA R. K. NARAYAN was born on October 10, 1906, in Madras, South India, and educated there and at Maharaja’s College in Mysore. His first novel, Swami and Friends (1935), and its successor, The Bachelor of Arts (1937), are both set in the fictional territory of Malgudi, of which John Updike wrote, “Few writers since Dickens can match the effect of colorful teeming that Narayan’s fictional city of Malgudi conveys; its population is as sharply chiseled as a temple frieze, and as endless, with always, one feels, more characters round the corner.” Narayan wrote many more novels set in Malgudi, including The English Teacher (1945), The Financial Expert (1952), and The Guide (1958), which won him the Sahitya Akademi (India’s National Academy of Letters) Award, his country’s highest honor. His collections of short fiction include A Horse and Two Goats, Malgudi Days, and Under the Banyan Tree. Graham Greene, Narayan’s friend and literary champion, said, “He has offered me a second home. Without him I could never have known what it is like to be Indian.” Narayan’s fiction earned him comparisons to the work of writers including Anton Chekhov, William Faulkner, O. -

Volume 1: Imaginative Promptings: on 'Translating'

Volume 1: Imaginative Promptings: on ‘translating’ Paul et Virginie Volume 2: Genie and Paul: A Novel Natasha Soobramanien PhD in Creative and Critical Writing University of East Anglia Faculty of Arts and Humanities September 2010 Abstract This thesis comprises a novel, Genie and Paul, and a critical commentary which posits Genie and Paul as a ‘translation’ of J. J. H. Bernadin de Saint-Pierre’s, Paul et Virginie, an eighteenth-century French novel set in colonial Mauritius. Genie and Paul explores its British Mauritian protagonists’ complex sense of cultural identity, with reference to Paul et Virginie, a novel of great personal significance to me. In my critical commentary, I explore the ways in which my novel creatively engages with Paul et Virginie, and make a case for using the term ‘translation’ to define my rewriting of it, with reference to the growing body of postcolonial literary translation theory. I examine the significance of Paul et Virginie to the development of my identity as a writer, and argue that my ‘translation’ is an effective method of negotiating my complex relationship both to Mauritius, and to the European literary canon. I contextualise this discussion by looking at writers who share a similarly equivocal relationship with their cultural background, chiefly V.S. Naipaul and Pankaj Mishra. I consider how these writers’ backgrounds inflect their respective relationships with literary tradition, and examine the strategies they have employed to negotiate this. Whereas Naipaul has been initially reluctant to admit to literary influences, Mishra overtly acknowledges his in The Romantics, his autobiographical first novel. I show how this novel is a ‘translation’ of a key text in Mishra’s personal canon, Flaubert’s A Sentimental Education, and I use this discussion as a model for the analysis of my own ‘translation’ of Paul et Virginie. -

Old Words, New Worlds: Revisiting the Modernity of Tradition

Old Words, New Worlds: Revisiting the Modernity of Tradition Ananya Vajpeyi n the Hindi film Raincoat (2004), review article we begin to look, Kalidasa and Krishna, Rituparno Ghosh presents a short story Vyasa and Valmiki are everywhere in the Iby O Henry in an Indian milieu. The The Modernity of Sanskrit by Simona Sawhney art and literature of modern India, as are place is contemporary middle class Kolkata; (Ranikhet: Permanent Black; co-published by University of many other authors, characters, tropes the main actors, drawn from Bollywood, Minnesota Press), 2009; pp 226, Rs 495 (HB). and narratives that invariably appear to us are at home in the present. Most of the as familiar, yet differently relevant in dif- conversation between various characters his updating and Indianising O Henry’s ferent contexts. They require no introduc- revolves around cell phones, TV channels, tale, but in his simultaneous reference to tion for any given audience, yet at each soap operas, air-conditioning and auto- post-colonial, colonial and pre-colonial new site where they turn up, as it were, mated teller machines, leaving us in no Bengali culture, and thus to a dense under- there is the interpretive space to figure out doubt as to the setting. But given that the belly of significance that gives weight to what exactly makes them pertinent on story is somewhat slow, and the acting by an otherwise trivial story. Calcutta’s status this occasion. Thus the work of writing the female lead, Aishwarya Rai indifferent as a big city, its urban decrepitude, its faded and reading is always ongoing, always at best, what gives the film its shadowed imperial grandeur and grinding poverty, inter-textual, always citational, and unfolds mood is its beautiful music, and the direc- these we already compute; so too the within a framework that blurs rather than tor’s obvious love for Kolkata. -

An Epistemic Thunderstorm: What We Learned and Failed to Learn from Jordan Peterson’S Rise to Fame1

An Epistemic Thunderstorm: What We Learned and Failed to Learn from 1 Jordan Peterson’s Rise to Fame Jonathan Rowson2 Abstract: The cultural pressure to endorse or reject public intellectuals wholesale can be problematic, perpetuating groupthink and diminishing scope for intellectual growth, societal maturation, and political imagination. On encountering public figures who appear to be both right and wrong, sometimes simultaneously, perhaps dangerously, there is scope to be more creative and less reactive in our response. In the illustrative case of Jordan Peterson, commentators often oriented their analysis within a conceptually moribund political spectrum; e.g. Peterson is “alt-right” attacking “the radical left.” Social media echo chambers lead some to read that Peterson’s “fanboys” were “misogynist trolls” while others heard that his critics were “virtue signaling snowflakes”. The tendency of print and broadcast media to seek a defining angle diminishes rather than distills complexity; for instance, Peterson’s fame was associated with a perceived crisis in masculinity, but that was not the whole story. “Petersonitis” is introduced here as a serious joke to describe the intellectual and emotional discomfort that arose from the author’s attempt to seek a fuller understanding of complex characters in a divisive political culture. In a response to Peterson’s book, 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos, twelve relatively dispassionate perspectives on his contribution are offered as an antidote to the language of allergy and infatuation that surrounded his rise to fame. Peterson is described here as symptomatic, multiphrenic, theatrical, solipsistic, sacralizing, hypervigilant, monocular, ideological, Manichean, Piagetian, masculine, and prismatic. First person language is used to reflect the author’s experience of Petersonitis, after having been drawn to Peterson’s online video lectures, debating with him in a public forum, and gradually clarifying the nature of the limitations in his outlook and approach. -

Chapter Five

Chapter Five: Assessment Chapter Five: Assessment Page 5.1. Multi-layer Evaluation: A Perspective through the Prism 5.1.1. Pankaj Mishra's Selected Works 342 5.1.2. Milan Kundera's Selected Works 361 5.2. Notes and References 385 5.1. Multi-layer Evaluation: A Perspective through the Prism Up to this part of the study, the intra/extra-textual features of the selected texts have been explored and reviewed as far as possible. At this point there will be a multi layer evaluation of the selected texts which are, by and large, both product of and engaged with the forces of globalization. Considering the relationship between globality, globalization and the chosen texts from Mishra and Kundera, here two relevant levels of assessment are concentrated upon. At one level, the selected texts are observed as bearing the reflections of some dimensions and effects of globalization within their events; being thematized within the texts globalization becomes more directly traceable. In the meantime and in a different fiinction, some parts of these selected texts are developed into platforms which could evoke, support and interpret various social, political, literary, and cultural aspects of globalization. The ideas and occasions which are reviewed at this level can partly clarify the topographical status of the selected works in relation to globalization and its debates. Of course, it may be noted that the qualities mentioned at this level are not necessarily applicable in a collective mode to all four selected texts. However, some of the features referred to in the discussion of this level may fit into the intra-textual section of the approach, as well. -

The Critic As Amateur Saikat Majumdar

The Critic as Amateur Saikat Majumdar New Literary History, Volume 48, Number 1, Winter 2017, pp. 1-25 (Article) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/652561 Access provided by University of Virginia Libraries & (Viva) (30 Mar 2017 14:24 GMT) The Critic as Amateur Saikat Majumdar n his memoir-essay, “Edmund Wilson in Benares,” Pankaj Mishra records a unique intellectual failure: his inability is to write an Ioriginal piece on Edmund Wilson, a critic who had enthralled him for several years. This failure took place in 1995, the year of Wilson’s centenary, which had prompted Mishra to try to write something about the American critic, ideally an “exposition of Wilson’s key books.”1 But he could not, he felt, come up with anything original: “What I wrote seemed to me too much like a reprise of what a lot of other people had already said about him” (EW 370). It becomes intriguingly clear that if Mishra had succeeded in writing the other piece, we would have never had his essay “Edmund Wilson in Benares,” a product of this very failure. A key reason for his inability to write the essay he had planned about Wilson, Mishra felt, was that he was “trying to write about him in the way an American or European writer would have” (EW 370). The essay he produced evokes, slowly but vividly, the meaning and the genealogy of this failure. But what does it offer instead? It is one of the most remarkable pieces of writing that I have encoun- tered anywhere: an account of four months Mishra spent in Benares in 1988. -

Chapter Three

Chapter Three: Pankaj Mishra and His World Chapter Three: Pankaj Mishra and His World Page 3.1. Introduction: Pankaj Mishra, Biography and His Works 3.1.1. Biography 125 3.1.2. Books 128 3.1.3. Selected Articles 129 3.1.4. Reviews 130 3.1.5. Appearances 132 3.1.6. Notes and References 133 3.2. Intra/Extra-textual Features of The Romantics and Butter Chicken in Ludhiana: Travels in Small Town India 3.2.1. The Romantics 134 3.2.1.1. General Overview 134 3.2.1.2. Intra-textual Features 136 3.2.1.2A. Setting 136 3.2.1.2.2. Plot 141 3.2.1.2.3. Narration, Narrator and Point of view 147 3.2.1.2.4. Themes 152 3.2.1.2.5. Characters 155 3.2.1.3. Extra-textual Features 161 3.2.1.4. Notes and References 166 3.2.2. Butter Chicken in Ludhiana: Travels in Small Town India 111 3.2.2.1. General Overview 172 3.2.2.2. hitra-textual Features 175 3.2.2.2.1. Genre 175 3.2.2.2.2. Itinerary and Setting 177 3.2.2.2.3. Narration/Narrator 185 3.2.2.2.4. Characterization 197 3.2.2.3. Extra-textual Features 205 3.2.2.4. Notes and References 208 "This is the truest function of a national literature: it holds up a mirror in whose unfamiliar reflections a nation slowly learns to recognize itself The writer, exercising his talent and imagination, discovers new subjects, or deepens old discoveries; and he himself grows in the process."' (Pankaj Mishra). -

Indian Writing in English

INDIAN WRITING IN ENGLISH Contents 1) English in India 3 2) Indian Fiction in English: An Introduction 6 3) Raja Rao 32 4) Mulk Raj Anand 34 5) R K Narayan 36 6) Sri Aurobindo 38 7) Kamala Markandaya’s Indian Women Protagonists 40 8) Shashi Deshpande 47 9) Arun Joshi 50 10) The Shadow Lines 54 11) Early Indian English Poetry 57 a. Toru Dutt 59 b. Michael Madusudan Dutta 60 c. Sarojini Naidu 62 12) Contemporary Indian English Poetry 63 13) The Use of Irony in Indian English Poetry 68 14) A K Ramanujan 73 15) Nissim Ezekiel 79 16) Kamala Das 81 17) Girish Karnad as a Playwright 83 Vallaths TES 2 English in India I’ll have them fly to India for gold, Ransack the ocean for oriental pearl! These are the words of Dr. Faustus in Christopher Marlowe’s play Dr Faustus. The play was written almost in the same year as the East India Company launched upon its trading adventures in India. Marlowe’s words here symbolize the Elizabethan spirit of adventure. Dr. Faustus sells his soul to the devil, converts his knowledge into power, and power into an earthly paradise. British East India Company had a similar ambition, the ambition of power. The English came to India primarily as traders. The East India Company, chartered on 31 December, 1600, was a body of the most enterprising merchants of the City of London. Slowly, the trading organization grew into a ruling power. As a ruler, the Company thought of its obligation to civilize the natives; they offered their language by way of education in exchange for the loyalty and commitment of their subjects. -

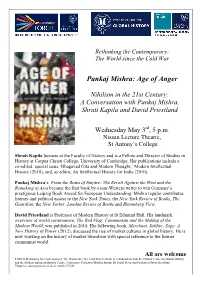

Pankaj Mishra: Age of Anger

Rethinking the Contemporary: The World since the Cold War Pankaj Mishra: Age of Anger Nihilism in the 21st Century: A Conversation with Pankaj Mishra, Shruti Kapila and David Priestland Wednesday May 3rd, 5 p.m. Nissan Lecture Theatre, St Antony’s College Shruti Kapila lectures at the Faculty of History and is a Fellow and Director of Studies in History at Corpus Christi College, University of Cambridge. Her publications include a co-edited special issue ‘Bhagavad Gita and Modern Thought,’ Modern Intellectual History (2010), and, as editor, An Intellectual History for India (2010). Pankaj Mishra’s From the Ruins of Empire: The Revolt Against the West and the Remaking of Asia became the first book by a non-Western writer to win Germany’s prestigious Leipzig Book Award for European Understanding. Mishra regular contributes literary and political essays to the New York Times, the New York Review of Books, The Guardian, the New Yorker, London Review of Books and Bloomberg View. David Priestland is Professor of Modern History at St Edmund Hall. His landmark overview of world communism, The Red Flag: Communism and the Making of the Modern World, was published in 2010. His following book, Merchant, Soldier, Sage: A New History of Power (2012), discussed the rise of market cultures in global history. He is now working on the history of market liberalism with special reference to the former communist world. All are welcome TORCH Rethinking the Contemporary: The World since the Cold War Network in collaboration with the Oxford Centre for Global History and the Modern European History Centre.