X Erox U Niversity M Icrofilms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hellenic Saga Gaia (Earth)

The Hellenic Saga Gaia (Earth) Uranus (Heaven) Oceanus = Tethys Iapetus (Titan) = Clymene Themis Atlas Menoetius Prometheus Epimetheus = Pandora Prometheus • “Prometheus made humans out of earth and water, and he also gave them fire…” (Apollodorus Library 1.7.1) • … “and scatter-brained Epimetheus from the first was a mischief to men who eat bread; for it was he who first took of Zeus the woman, the maiden whom he had formed” (Hesiod Theogony ca. 509) Prometheus and Zeus • Zeus concealed the secret of life • Trick of the meat and fat • Zeus concealed fire • Prometheus stole it and gave it to man • Freidrich H. Fuger, 1751 - 1818 • Zeus ordered the creation of Pandora • Zeus chained Prometheus to a mountain • The accounts here are many and confused Maxfield Parish Prometheus 1919 Prometheus Chained Dirck van Baburen 1594 - 1624 Prometheus Nicolas-Sébastien Adam 1705 - 1778 Frankenstein: The Modern Prometheus • Novel by Mary Shelly • First published in 1818. • The first true Science Fiction novel • Victor Frankenstein is Prometheus • As with the story of Prometheus, the novel asks about cause and effect, and about responsibility. • Is man accountable for his creations? • Is God? • Are there moral, ethical constraints on man’s creative urges? Mary Shelly • “I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion. Frightful must it be; for supremely frightful would be the effect of any human endeavour to mock the stupendous mechanism of the Creator of the world” (Introduction to the 1831 edition) Did I request thee, from my clay To mould me man? Did I solicit thee From darkness to promote me? John Milton, Paradise Lost 10. -

Sample Odyssey Passage

The Odyssey of Homer Translated from Greek into English prose in 1879 by S.H. Butcher and Andrew Lang. Book I In a Council of the Gods, Poseidon absent, Pallas procureth an order for the restitution of Odysseus; and appearing to his son Telemachus, in human shape, adviseth him to complain of the Wooers before the Council of the people, and then go to Pylos and Sparta to inquire about his father. Tell me, Muse, of that man, so ready at need, who wandered far and wide, after he had sacked the sacred citadel of Troy, and many were the men whose towns he saw and whose mind he learnt, yea, and many the woes he suffered in his heart upon the deep, striving to win his own life and the return of his company. Nay, but even so he saved not his company, though he desired it sore. For through the blindness of their own hearts they perished, fools, who devoured the oxen of Helios Hyperion: but the god took from them their day of returning. Of these things, goddess, daughter of Zeus, whencesoever thou hast heard thereof, declare thou even unto us. Now all the rest, as many as fled from sheer destruction, were at home, and had escaped both war and sea, but Odysseus only, craving for his wife and for his homeward path, the lady nymph Calypso held, that fair goddess, in her hollow caves, longing to have him for her lord. But when now the year had come in the courses of the seasons, wherein the gods had ordained that he should return home to Ithaca, not even there was he quit of labours, not even among his own; but all the gods had pity on him save Poseidon, who raged continually against godlike Odysseus, till he came to his own country. -

Early Theories of Foreignness (Kennedy, RECW Ch 1 Pp

Clas 122 2017 Mon Oct 2: Homer and Hesiod: Early Theories of Foreignness (Kennedy, RECW Ch 1 pp. 3-13) Overview of Homer's Odyssey -- a map of the world imagined by speakers of Greek The poem itself invites its audience to think about: What is a good society? What is a good leader? As readers here and now, we can also ask critical Questions: What are the poem's blind spots? How does the poem encourage its audience to think and behave? Do the poem's ideas about a good society and a good leader have meaning today? The images below come from a series of collages and paintings by Romare Bearden (1911-1988). The Smithsonian Institution organized a bautiful exhibit of the series recently, and there is a good free app (showing many of the works and adding audio commentary) available for I phone and android; search for "A Black Odyssey" where you get apps. As our story begins ..... During his journey back to his home in Ithaca after the war at Troy, Odysseus is on the island of Calypso. Athena asks Zeus if Odysseus can come home to Ithaca. Zeus says yes, and sends Hermes to tell Calypso that Odysseus needs to come home. Calypso lets Odysseus build a raft and he departs. This is only possible because .... RECW 1.1 Od. 1.22-26: Poseidon, the god of the sea, is visiting the Ethiopians, and thus is not watching Odysseus. Poseidon had been thwarting the homecoming because of the way that Odysseus treated the Cyclops Polyphemus, who was descended from Poseidon. -

AGAMEMNON PROLOGUE: Lines 1-39

AGAMEMNON PROLOGUE: Lines 1-39 GUARD: Watching from a WatchTower in Argos for the beacon of light announcing the fall of Troy! Laments of how long he has waited and watched with “elbow-bent, doglike,” without sleep. At prologues end, the beacon of light has brightened the sky. Guard has much joy, and hope that this will turn the house around. Imagery: Light/ Dark Lines 16-18: We know there is something amiss with how the house is being “administered.” The mix of anticipation and foreboding sets mood of the play. Something’s Coming. PARADOS: Prelude Lines 40- 103 What Character is the Chorus Playing? Lines 72-76 PRELUDE Continued WHAT’S GOING ON? - Trojan War has just ended after 10 years, but how did it began? MENELAUS- KING OF SPARTA AGAMEMNON- KING OF ARGOS/ BROTHER OF MENELAUS Vs. PARIS (ALEXANDER)- PRINCE OF TROY HELEN- Once Wife of Menelaus now Wife of Paris (Clytemnestra's Sister) “Promiscuous Girl, Stop Teasing Me” NESTRA: WAIT, SO MY HUSBAND LEFT TO FIGHT A WAR TO FORCE MY \ SISTER TO STAY MARRIED TO HIS BROTHER? CHORUS: YES, CLYTEMNESTRA. NESTRA: ALRIGHT, COOL. SO, I’M JUST GONNA TRY TO TAKE CARE OF THIS KINGDOM OF ARGOS THEN, I GUESS. CHORUS: BUT, WHY ARE YOU BURNING ALL THESE SACRIFICES FOR THE GODS AND ORDERING ALL THESE CELEBRATIONS? NESTRA: WELL… CHORUS: IMMA LET YOU FINISH BUT, I GOTTA TELL YOU ABOUT THIS OTHER MESS REAL QUICK.. PARADOS: Three-Part ODE Part One: STROPHE (East To West, or From Stage Right) ANTISTROPHE (West to East, or From Stage Left) EPODE (From Center, could be by one member of chorus or multiple) CALCHAS: I’m a Soothsayer and those two eagles eating that pregnant rabbit means VICTORY for the two brothers! ARTEMIS: Yes, but those eagles killed a pregnant rabbit. -

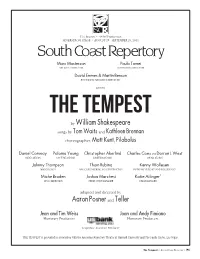

By William Shakespeare Aaron Posner and Teller

51st Season • 483rd Production SEGERSTROM STAGE / AUGUST 29 - SEPTEMBER 28, 2014 Marc Masterson Paula Tomei ARTISTIC DIRECTOR MANAGING DIRECTOR David Emmes & Martin Benson FOUNDING ARTISTIC DIRECTORS presents THE TEMPEST by William Shakespeare songs by Tom Waits and Kathleen Brennan choreographer, Matt Kent, Pilobolus Daniel Conway Paloma Young Christopher Akerlind Charles Coes AND Darron L West SCENIC DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN LIGHTING DESIGN SOUND DESIGN Johnny Thompson Thom Rubino Kenny Wollesen MAGIC DESIGN MAGIC ENGINEERING AND CONSTRUCTION INSTRUMENT DESIGN AND WOLLESONICS Miche Braden Joshua Marchesi Katie Ailinger* MUSIC DIRECTION PRODUCTION MANAGER STAGE MANAGER adapted and directed by Aaron Posner and Teller Jean and Tim Weiss Joan and Andy Fimiano Honorary Producers Honorary Producers Corporate Associate Producer THE TEMPEST is presented in association with the American Repertory Theater at Harvard University and The Smith Center, Las Vegas. The Tempest • SOUTH COAST REPERTORY • P1 CAST OF CHARACTERS Prospero, a magician, a father and the true Duke of Milan ............................ Tom Nelis* Miranda, his daughter .......................................................................... Charlotte Graham* Ariel, his spirit servant .................................................................................... Nate Dendy* Caliban, his adopted slave .............................. Zachary Eisenstat*, Manelich Minniefee* Antonio, Prospero’s brother, the usurping Duke of Milan ......................... Louis Butelli* Gonzala, -

Trojan Women: Introduction

Trojan Women: Introduction 1. Gods in the Trojan Women Two gods take the stage in the prologue to Trojan Women. Are these gods real or abstract? In the prologue, with its monologue by Poseidon followed by a dialogue between the master of the sea and Athena, we see them as real, as actors (perhaps statelier than us, and accoutered with their traditional props, a trident for the sea god, a helmet for Zeus’ daughter). They are otherwise quite ordinary people with their loves and hates and with their infernal flexibility whether moral or emotional. They keep their emotional side removed from humans, distance which will soon become physical. Poseidon cannot stay in Troy, because the citizens don’t worship him any longer. He may feel sadness or regret, but not mourning for the people who once worshiped but now are dead or soon to be dispersed. He is not present for the destruction of the towers that signal his final absence and the diaspora of his Phrygians. He takes pride in the building of the walls, perfected by the use of mason’s rules. After the divine departures, the play proceeds to the inanition of his and Apollo’s labor, with one more use for the towers before they are wiped from the face of the earth. Nothing will be left. It is true, as Hecuba claims, her last vestige of pride, the name of Troy remains, but the place wandered about throughout antiquity and into the modern age. At the end of his monologue Poseidon can still say farewell to the towers. -

Sundance Institute Announces Casts for Summer Theatre Laboratory

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE For more information contact: June 21, 2006 Irene Cho [email protected], 801.328.3456 SUNDANCE INSTITUTE ANNOUNCES CASTS FOR SUMMER THEATRE LABORATORY AWARD-WINNING ACTORS ANTHONY RAPP, RAÚL ESPARZA AND OTHERS TO WORKSHOP SEVEN NEW PLAYS AT JULY LAB IN UTAH Salt Lake City, UT – Today, Sundance Institute announced the acting ensemble for the 2006 Sundance Institute Theatre Laboratory, to be held July 10-30, 2006 at the Sundance Resort in Utah. The company includes: Bradford Anderson, Nancy Anderson, Whitney Bashor, Judy Blazer, Reg E. Cathey, Will Chase, Johanna Day, Raúl Esparza, Jordan Gelber, Kimberly Hebert Gregory, Carla Harting, Roderick Hill, Nicholas Hormann, Christina Kirk, Ezra Knight, Judy Kuhn, Anika Larsen, Piter Marek, Kelly McCreary, Chris Messina, Jennifer Mudge, Novella Nelson, Toi Perkins, Anthony Rapp, Gareth Saxe, Tregoney Shepherd, Michael Stuhlbarg and Price Waldman. The seven plays to be developed at the 2006 Sundance Institute Theatre Laboratory include: CITIZEN JOSH, by Josh Kornbluth, directed by David Dower, an improvisational solo show which strives to rescue “democracy” from the sloganeers in a personal autobiographical format; CURRENT NOBODY, by Melissa James Gibson, directed by Daniel Aukin, a modern reinterpretation of Homer’s The Odyssey; GEOMETRY OF FIRE, by Stephen Belber, directed by Lucie Tiberghien, which weaves the story of an American reservist just back from Iraq and a Saudi-American citizen investigating his father’s death; THE EVILDOERS, by David Adjmi, directed by Rebecca Taichman, a play in which the marriage of two couples unravel in a dark yet comedic context; …AND JESUS MOONWALKS THE MISSISSIPPI, by Marcus Gardley, directed by Matt August, a poetic retelling of the Demeter myth set during the Civil War; KIND HEARTS AND CORONETS, book by Robert L. -

Naming the Extrasolar Planets

Naming the extrasolar planets W. Lyra Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, K¨onigstuhl 17, 69177, Heidelberg, Germany [email protected] Abstract and OGLE-TR-182 b, which does not help educators convey the message that these planets are quite similar to Jupiter. Extrasolar planets are not named and are referred to only In stark contrast, the sentence“planet Apollo is a gas giant by their assigned scientific designation. The reason given like Jupiter” is heavily - yet invisibly - coated with Coper- by the IAU to not name the planets is that it is consid- nicanism. ered impractical as planets are expected to be common. I One reason given by the IAU for not considering naming advance some reasons as to why this logic is flawed, and sug- the extrasolar planets is that it is a task deemed impractical. gest names for the 403 extrasolar planet candidates known One source is quoted as having said “if planets are found to as of Oct 2009. The names follow a scheme of association occur very frequently in the Universe, a system of individual with the constellation that the host star pertains to, and names for planets might well rapidly be found equally im- therefore are mostly drawn from Roman-Greek mythology. practicable as it is for stars, as planet discoveries progress.” Other mythologies may also be used given that a suitable 1. This leads to a second argument. It is indeed impractical association is established. to name all stars. But some stars are named nonetheless. In fact, all other classes of astronomical bodies are named. -

From the Odyssey, Part 1: the Adventures of Odysseus

from The Odyssey, Part 1: The Adventures of Odysseus Homer, translated by Robert Fitzgerald ANCHOR TEXT | EPIC POEM Archivart/Alamy Stock Photo Archivart/Alamy This version of the selection alternates original text The poet, Homer, begins his epic by asking a Muse1 to help him tell the story of with summarized passages. Odysseus. Odysseus, Homer says, is famous for fighting in the Trojan War and for Dotted lines appear next to surviving a difficult journey home from Troy.2 Odysseus saw many places and met many the summarized passages. people in his travels. He tried to return his shipmates safely to their families, but they 3 made the mistake of killing the cattle of Helios, for which they paid with their lives. NOTES Homer once again asks the Muse to help him tell the tale. The next section of the poem takes place 10 years after the Trojan War. Odysseus arrives in an island kingdom called Phaeacia, which is ruled by Alcinous. Alcinous asks Odysseus to tell him the story of his travels. I am Laertes’4 son, Odysseus. Men hold me formidable for guile5 in peace and war: this fame has gone abroad to the sky’s rim. My home is on the peaked sea-mark of Ithaca6 under Mount Neion’s wind-blown robe of leaves, in sight of other islands—Dulichium, Same, wooded Zacynthus—Ithaca being most lofty in that coastal sea, and northwest, while the rest lie east and south. A rocky isle, but good for a boy’s training; I shall not see on earth a place more dear, though I have been detained long by Calypso,7 loveliest among goddesses, who held me in her smooth caves to be her heart’s delight, as Circe of Aeaea,8 the enchantress, desired me, and detained me in her hall. -

A New Perspective on Revenge and Justice in Homer Judith Stanton Bridgewater State College

Bridgewater Review Volume 2 | Issue 2 Article 13 Mar-1984 Research Note: A New Perspective on Revenge and Justice in Homer Judith Stanton Bridgewater State College Recommended Citation Stanton, Judith (1984). Research Note: A New Perspective on Revenge and Justice in Homer. Bridgewater Review, 2(2), 26-27. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/br_rev/vol2/iss2/13 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. Cultural Commentary Continued table for more moves, brings it out a third RESEARCH NOTE time for a last look and then manipulates it for the last time under the table, finally achieving cubical perfection. A New Perspective on Revenge Is this game playing spirit, native to all of us, at the heart of mathematics? Is and Justice in Homer Judith Stanton mathematics a sort of game, albeit with Assistant Professor of English serious applications? I think that it is. I am reminded of Jacob Bronowski who Most of us are aware that our idea of considers this question in his beautiful work, justice comes largely from Ancient Greece. so optimistic for mankind, The Ascent of But we might be surprised at how old Greek Man. At one point Bronowski is explaining justice really is. Classical Athens (490·323 symmetry in nature and art. He takes us to B.C.), to which we owe much of our the Alhambra, where in the baths of the understanding of justice, was itself heir to a harem we see motifs of "wind-swept" system of revenge justice that was older still triangles in perfect hexagonal collaboration -- perhaps as old as Hie Mycenaean period filling the walls. -

Iliad Teacher Sample

CONTENTS Teaching Guidelines ...................................................4 Appendix Book 1: The Anger of Achilles ...................................6 Genealogies ...............................................................57 Book 2: Before Battle ................................................8 Alternate Names in Homer’s Iliad ..............................58 Book 3: Dueling .........................................................10 The Friends and Foes of Homer’s Iliad ......................59 Book 4: From Truce to War ........................................12 Weaponry and Armor in Homer..................................61 Book 5: Diomed’s Day ...............................................14 Ship Terminology in Homer .......................................63 Book 6: Tides of War .................................................16 Character References in the Iliad ...............................65 Book 7: A Duel, a Truce, a Wall .................................18 Iliad Tests & Keys .....................................................67 Book 8: Zeus Takes Charge ........................................20 Book 9: Agamemnon’s Day ........................................22 Book 10: Spies ...........................................................24 Book 11: The Wounded ..............................................26 Book 12: Breach ........................................................28 Book 13: Tug of War ..................................................30 Book 14: Return to the Fray .......................................32 -

"Works Cited." Experiencing Hektor: Character in the . London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017

Kozak, Lynn. "Works Cited." Experiencing Hektor: Character in the . London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017. 281–298. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 5 Oct. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474245470.0009>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 5 October 2021, 20:46 UTC. Copyright © Lynn Kozak 2017. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. W o r k s C i t e d Abad-Santos , A. ( 2016 ), ‘ Negan has fi nally arrived on Th e Walking Dead. Here’s why he’s so important. ’ vox.com , 3 April . Available online: http://www.vox.com/2016/4/3/ 11353504/walking- dead-negan Adams , E. ( 2015 ) ‘ Game of Th rones (newbies) : “ Hardhome” ’, A.V. Club , 31 May . Available online: http://www.avclub.com/tvclub/game- thrones-newbies- hardhome-220153 Ahl , F. ( 1989 ), ‘ Homer, Vergil, and complex narrative structures in Latin epic: an essay ’, Illinois Classical Studies, 14 ( 1/2 ): 1–31 . Alden , M. ( 2000 ), Homer Beside Himself: Para-Narratives in the I l i a d , O x f o r d : O x f o r d University Press . Alexiou , M. ( 1974 ), Th e Ritual Lament in Greek Tradition , O x f o r d : O x f o r d U n i v e r s i t y Press . Allen , R. C. ( 2004 ), ‘ Making Sense of Soaps ’, in Th e Television Studies Reader , e d s R . C . H i l l a n d A n n e t t e H i l l , R o u t l e d g e .