UNCCD Knowledge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Viaggi Viaggi N O U I M

altr un o i m r viaggi o p n o d c o s altr viaggi viaggi un o i m r o p n o d c o s dal 23 aprile al 2 maggio 2020 Libano: sentieri di storia il programma dettagliato Giorno 1: giovedì 23 aprile Arrivo all’aeroporto di Beirut nel primo pomeriggio con il volo Alitalia da Roma Trasferimento in pulmino al villaggio di Ehmej Pernottamento a Ehmej in 2 guest house fondate da COSPE: “La Vallée Blanche” Bed and Breakfast “Mosaic House” Cena a “La Vallée Blanche” Giorno 2: venerdì 24 aprile Colazione Visita dei progetti di COSPE a Ehmej e incontro con la municipalità di Ehmej Visita alle attività di educazione ambientale a Tannourine Visita alla Cooperativa Mar Semaan Hadath el Jebbeh, con i nuovi punti vendita per prodotti agricoli Trasferimento a Bcharré Visita al museo Gibran, ospitato nel monastero di Mar Sarkis e dedicato alla vita dello scrittore e intellettuale libanese Gibran Khalil Gibran, nativo di Bcharré Pernottamento a Bcharré, sistemazione nella guest house “Tiger house” Cena in un ristorante locale Giorno 3: sabato 25 aprile Colazione Trekking sulla sezione 7 del Lebanon Mountain Trail da Bcharré a Freidis (10,7 km - salita 605 m – discesa 1277 m) Si passa attraverso la famosa valle di Qadisha (sito patrimonio mondiale UNESCO), dallo spettacolare paesaggio naturale e con residue foreste di cedri del Libano Trasferimento da Freidis al monastero Mar Antonios di Qozhaya Visita del museo del monastero di Mar Antonios (con la prima macchina da stampa del Medio Oriente) Pernottamento nel monastero di Mar Antonios a Qozhaya Cena al convento. -

The Israeli Experience in Lebanon, 1982-1985

THE ISRAELI EXPERIENCE IN LEBANON, 1982-1985 Major George C. Solley Marine Corps Command and Staff College Marine Corps Development and Education Command Quantico, Virginia 10 May 1987 ABSTRACT Author: Solley, George C., Major, USMC Title: Israel's Lebanon War, 1982-1985 Date: 16 February 1987 On 6 June 1982, the armed forces of Israel invaded Lebanon in a campaign which, although initially perceived as limited in purpose, scope, and duration, would become the longest and most controversial military action in Israel's history. Operation Peace for Galilee was launched to meet five national strategy goals: (1) eliminate the PLO threat to Israel's northern border; (2) destroy the PLO infrastructure in Lebanon; (3) remove Syrian military presence in the Bekaa Valley and reduce its influence in Lebanon; (4) create a stable Lebanese government; and (5) therefore strengthen Israel's position in the West Bank. This study examines Israel's experience in Lebanon from the growth of a significant PLO threat during the 1970's to the present, concentrating on the events from the initial Israeli invasion in June 1982 to the completion of the withdrawal in June 1985. In doing so, the study pays particular attention to three aspects of the war: military operations, strategic goals, and overall results. The examination of the Lebanon War lends itself to division into three parts. Part One recounts the background necessary for an understanding of the war's context -- the growth of PLO power in Lebanon, the internal power struggle in Lebanon during the long and continuing civil war, and Israeli involvement in Lebanon prior to 1982. -

Usaid/Lebanon Lebanon Industry Value Chain Development (Livcd) Project

USAID/LEBANON LEBANON INDUSTRY VALUE CHAIN DEVELOPMENT (LIVCD) PROJECT LIVCD QUARTERLY PROGRESS REPORT - YEAR 6, QUARTER 3 APRIL 1 – JUNE 30, 2018 JULY 2018 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by DAI. Contents ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................................. 3 PROJECT OVERVIEW ............................................................................................................. 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.......................................................................................................... 6 KEY HIGHLIGHTS ................................................................................................................... 8 PERFORMANCE INDICATOR RESULTS FOR Q3 FY18 AND LIFE OF PROJECT ........... 11 IMPROVE VALUE CHAIN COMPETITIVENESS ................................................................. 15 PROCESSED FOODS VALUE CHAIN .................................................................................. 15 RURAL TOURISM VALUE CHAIN........................................................................................ 23 OLIVE OIL VALUE CHAIN .......................................................................................................... 31 POME FRUIT VALUE CHAIN (APPLES AND PEARS) ....................................................... 40 CHERRY VALUE CHAIN ...................................................................................................... -

Assessing Water Quality Management Options in the Upper Litani Basin, Lebanon, Using an Integrated GIS-Based Decision Support System

Environmental Modelling & Software 23 (2008) 1327–1337 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Environmental Modelling & Software journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/envsoft Assessing water quality management options in the Upper Litani Basin, Lebanon, using an integrated GIS-based decision support system Hamed Assaf a,*, Mark Saadeh b,1 a Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Faculty of Engineering and Architecture, American University of Beirut, AUB POBox 11-0236 Riad El Solh, Beirut 1107 2020, Lebanon b Water Quality Department, Litani River Authority, Beirut, Lebanon article info abstract Article history: The widespread and relentless discharge of untreated wastewater into the Upper Litani Basin (ULB) river Received 14 September 2007 system in Lebanon has reached staggering levels rendering its water unfit for most uses especially during Received in revised form 18 March 2008 the drier times of the year. Despite the call by governmental and non-governmental agencies to develop Accepted 19 March 2008 several wastewater treatment plants and sewage networks in an effort to control this problem, these Available online 5 May 2008 efforts do not seem to be coordinated or based on comprehensive and integrated assessments of current and projected conditions in the basin. Keywords: This paper provides an overview of the development and implementation of an integrated decision Water support system (DSS) designed to help policy makers and other stakeholders have a clearer un- Environmental planning Water quality control derstanding of the key factors and processes involved in the sewage induced degradation of surface Decision support systems water quality in the ULB, and formulate, assess and evaluate alternative management plans. -

Layout CAZA AAKAR.Indd

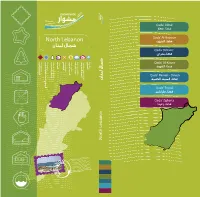

Qada’ Akkar North Lebanon Qada’ Al-Batroun Qada’ Bcharre Monuments Recreation Hotels Restaurants Handicrafts Bed & Breakfast Furnished Apartments Natural Attractions Beaches Qada’ Al-Koura Qada’ Minieh - Dinieh Qada’ Tripoli Qada’ Zgharta North Lebanon Table of Contents äÉjƒàëªdG Qada’ Akkar 1 QɵY AÉ°†b Map 2 á£jôîdG A’aidamoun 4-27 ¿ƒeó«Y Al-Bireh 5-27 √ô«ÑdG Al-Sahleh 6-27 á∏¡°ùdG A’andaqet 7-28 â≤æY A’arqa 8-28 ÉbôY Danbo 9-29 ƒÑfO Deir Jenine 10-29 ø«æL ôjO Fnaideq 11-29 ¥ó«æa Haizouq 12-30 ¥hõ«M Kfarnoun 13-30 ¿ƒfôØc Mounjez 14-31 õéæe Qounia 15-31 É«æb Akroum 15-32 ΩhôcCG Al-Daghli 16-32 »∏ZódG Sheikh Znad 17-33 OÉfR ï«°T Al-Qoubayat 18-33 äÉ«Ñ≤dG Qlaya’at 19-34 äÉ©«∏b Berqayel 20-34 πjÉbôH Halba 21-35 ÉÑ∏M Rahbeh 22-35 ¬ÑMQ Zouk Hadara 23-36 √QGóM ¥hR Sheikh Taba 24-36 ÉHÉW ï«°T Akkar Al-A’atiqa 25-37 á≤«à©dG QɵY Minyara 26-37 √QÉ«æe Qada’ Al-Batroun 69 ¿hôàÑdG AÉ°†b Map 40 á£jôîdG Kouba 42-66 ÉHƒc Bajdarfel 43-66 πaQóéH Wajh Al-Hajar 44-67 ôéëdG ¬Lh Hamat 45-67 äÉeÉM Bcha’aleh 56-68 ¬∏©°ûH Kour (or Kour Al-Jundi) 47-69 (…óæédG Qƒc hCG) Qƒc Sghar 48-69 Qɨ°U Mar Mama 49-70 ÉeÉe QÉe Racha 50-70 É°TGQ Kfifan 51-70 ¿ÉØ«Øc Jran 52-71 ¿GôL Ram 53-72 ΩGQ Smar Jbeil 54-72 π«ÑL Qɪ°S Rachana 55-73 ÉfÉ°TGQ Kfar Helda 56-74 Gó∏MôØc Kfour Al-Arabi 57-74 »Hô©dG QƒØc Hardine 58-75 øjOôM Ras Nhash 59-75 ¢TÉëf ¢SGQ Al-Batroun 60-76 ¿hôàÑdG Tannourine 62-78 øjQƒæJ Douma 64-77 ÉehO Assia 65-79 É«°UCG Qada’ Bcharre 81 …ô°ûH AÉ°†b Map 82 á£jôîdG Beqa’a Kafra 84-97 GôØc ´É≤H Hasroun 85-98 ¿hô°üM Bcharre 86-97 …ô°ûH Al-Diman 88-99 ¿ÉªjódG Hadath -

The World Bank

Document of The World Bank Report No: ICR2675 Public Disclosure Authorized IMPLEMENTATION COMPLETION AND RESULTS REPORT (TF-58084) Public Disclosure Authorized ON A GRANT IN THE AMOUNT OF US$ 5 MILLION TO THE LEBANESE REPUBLIC FOR THE EMERGENCY POWER SECTOR REFORM CAPACITY REINFORCEMENT PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized June 20, 2013 Sustainable Development Department Middle East and North Africa Region Public Disclosure Authorized 1 CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS Exchange Rate Effective June 18, 2013 Currency Unit = Lebanese Pound 1.00 = US$ 0.000662 US$ 1.00 = 1,511.51 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS CAS Country Assistance Strategy CDR Council for Development and Reconstruction DSP Distribution Service Provider DPL Development Policy Loan EdL Lebanese Power Company (“Electricité du Liban”) ESIA Economic and Social Impact Assessment FM Financial Management FSRU Floating Storage and Regasification Unit GoL Government of Lebanon HCP Higher Council for Privatization ISN Interim Strategy Note ISR Implementation and Status Report LNG Liquefied Natural Gas MMHLC Multi-Ministry Higher Level Committee MOEW Ministry of Energy and Water PDO Project Development Objective PPES Policy Paper for the Electricity Sector PRG Partial Risk Guarantee T&D Transmission and Distribution TFL Trust Fund for Lebanon WB World Bank Vice President: Inger Andersen Country Director: Ferid Belhaj Sector Manager: Charles Joseph Cormier Project Team Leader: Simon J. Stolp ICR Team Leader: Daniel Camos Daurella 2 LEBANESE REPUBLIC Emergency Power Sector Reform Capacity Reinforcement Project CONTENTS Data Sheet A. Basic Information B. Key Dates C. Ratings Summary D. Sector and Theme Codes E. Bank Staff F. Results Framework Analysis G. Ratings of Project Performance in ISRs H. Restructuring I. -

Usaid/Lebanon Lebanon Industry Value Chain Development (Livcd) Project

USAID/LEBANON LEBANON INDUSTRY VALUE CHAIN DEVELOPMENT (LIVCD) PROJECT LIVCD QUARTERLY PROGRESS REPORT JULY 1ST TO SEPTEMBER 30TH, 2013 – Q4 2013 Program Title: USAID/ LEBANON INDUSTRY VALUE CHAIN DEVELOPMENT (LIVCD) PROJECT Sponsoring USAID Office: USAID/Lebanon- Office of Economic Growth Contract Number: AID-268-C-12-00001 Contractor: DAI Date of Publication: July 2013 Author: DAI OCTOBER 2013 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by DAI. CONTENTS CONTENTS ....................................................................................................................... III INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 4 1.1 PROGRAM OVERVIEW AND OBJECTIVES ............................................................... 4 1.2 OVERVIEW OF QUARTERLY REPORT ............................................................................ 4 1.0 WORK PLAN INITIAL IMPLEMENTATION .............................................................. 6 2.1 VALUE CHAIN SELECTION AND WORK PLAN PREPARATION ........................................ 6 2.2 IMPLEMENTATION OF PRIORITY ACTIVITIES IN EACH VALUE CHAIN ............................. 7 2.2.1 CROSS-CUTTING VALUE CHAIN ACTIVITIES ............................................................. 7 2.2.2 FLORICULTURE ....................................................................................................... 9 2.2.3 GRAPES .................................................................................................................. -

Lebanon’S National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan

Lebanon’s National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan Republic of Lebanon Ministry of Environment BACKGROUND INFORMATION The Revision/Updating of the National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP) of Lebanon was conducted using funds from: The Global Environment Facility (GEF) 1818 H Street, NW, Mail Stop P4-400 Washington, DC 20433 USA Tel: (202) 473-0508 Fax: (202) 522-3240/3245 Web: www.thegef.org Project title: Lebanon: Biodiversity - Enabling Activity for the Revision/Updating of the National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP) and Preparation of the 5th National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), and Undertaking Clearing House Mechanism (CHM) Activities (GFL-2328-2716-4C37) Focal Point: Ms. Lara Samaha CBD Focal Point Head of Department of Ecosystems Ministry of Environment Assistant: Ms. Nada R Ghanem Managing Partner: United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) GEF Biodiversity, Land Degradation and Biosafety Unit Division of Environmental Policy Implementation (DEPI) UNEP Nairobi, Kenya P.O.Box: 30552 - 00100, Nairobi, Kenya Web: www.unep.org Executing Partner: Ministry of Environment – Lebanon Department of Ecosystems Lazarieh Center, 8th floor P.O Box: 11-2727 Beirut, Lebanon Tel: +961 1 976555 Fax: +961 1 976535 Web: www.moe.gov.lb Sub-Contracted Partner: Earth Link and Advanced Resources Development (ELARD) Amaret Chalhoub - Zalka Highway Fallas Building, 2nd Floor Tel: +961 1 888305 Fax: +961 896793 Web: www.elard-group.com Authors: Mr. Ricardo Khoury Ms. Nathalie Antoun Ms. Nayla Abou Habib Contributors: All stakeholders listed under Appendices C and D of this report have contributed to its preparation. Dr. Carla Khater, Dr. Manal Nader, and Dr. -

Water Sector Lebanon

WATER SECTOR LEBANON North : Informal Settlements (Active & <4 tents) Coverage Individuals Partner Donor ( 0 - 200 (! CISP No Donor 201 - 300 Zouq Bhannine ( (! SI UNICEF Rihaniyet-Miniyé ( Greater than 300 (! No Partner Minie Administrative boundaries Raouda-Aadoua Merkebta Nabi Youcheaa Caza Deir Aammar Mina N:3 Hraiqis Borj El-Yahoudiyé Mina N:1 Beddaoui Cadasters Mina N:2 Terbol-Miniyé Mzraat Kefraya Mina Jardin Trablous et Tabbaneh Qarhaiya Boussit Aasaymout Trablous Et-Tell Trablous El-Qobbe Aazqai Trablous jardins Trablous El-Haddadine, El-Hadid, El-Mharta Hailan Harf Es-Sayad Debaael Qarne Mejdlaiya Zgharta Aalma Btermaz Tripoli Kfar Chellane Beit Haouik Harf Es-Sayad Miriata Aachach Mrah Es-Srayj Haouaret-Miniyé Arde Trablous Ez-Zeitoun Bakhaaoun litige Kfar Habou Beit Zoud Aardat Qemmamine tarane Sfiré Rachaaine Jayroun Kharroub-Miniyé Kfar Bibnine Ras Masqa Mrah Es-Sfire Haql el Aazimé Zgharta Kfardlaqous Danha Qraine Qattiné-Miniyé Hazmiyet-Miniyé Beit El-Faqs Tallet Zgharta Aain Et-Tiné-Miniyé Asnoun Aassoun Barsa Qarsaita Bkeftine Mazraat Ajbeaa Izal Sir Ed-Danniyé Mazraat Ketrane Tripoli Kfarhoura Kfarhata Zgharta Hariq Zgharta Qalamoun Deddé Qarah Bach Deir Nbouh Mazraat Jnaid Mimrine Hraiche Bqaiaa El-Koura Khaldiyé Bqarsouna Nakhlé Kfarzaina Mrebbine Deir El-Balamand Batroumine Houakir Deir Jdeide Sakhra Btouratij Mazraat El-Kreme Qalhat Kfarchakhna Bechehhara Zaghartaghrine Iaal litige Kfar Kahel litige Enfé Zakroun Karm El-Mohr Bsebaal Kfaryachit Jarjour Aaymar litige Bdebba Kahf El-Malloul Bchannine Morh Kfarsghab -

Water Accounting in the Litani River Basin A

REMOTE SENSING FOR WATER PRODUCTIVITY WATER ACCOUNTING SERIES Water Accounting in the Litani River Basin A REMOTE SENSING FOR WATER PRODUCTIVITY WATER ACCOUNTING SERIES FAO and IHE Delft. 2019. Water Accounting in the Litani River Basin – Remote sensing for water productivity. Water accounting series. Rome. – Cover photograph: Wikimedia Commons Contents Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................... 1 Abbreviations and acronyms ........................................................................................................................ 2 Executive summary ....................................................................................................................................... 3 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 5 2 Methodology ......................................................................................................................................... 8 2.1 WaPOR database .......................................................................................................................... 8 2.1.1 Precipitation .......................................................................................................................... 8 2.1.2 Actual evapotranspiration and interception ....................................................................... 10 2.1.3 Basin scale water -

Hezbollah's "Land of Tunnels" - the North Korean-Iranian Connection

Hezbollah's "Land of Tunnels" - the North Korean-Iranian connection July 2021 By Tal Beeri Hezbollah's "Land of Tunnels" - the North Korean-Iranian connection In May 2021, we were exposed to Hamas' huge network of tunnels in the Gaza Strip, nicknamed by the IDF the "Hamas Metro”. In our estimation, after the Second Lebanon War of 2006, Hezbollah, with the help of the North Koreans and the Iranians, set up a project forming a network of "inter-regional" tunnels in Lebanon, a network significantly larger than the "Hamas" metro (in our assessment, Hamas used Iranian and North Korean knowledge to build its tunnels as well). It is not merely a network of offensive and infrastructure local tunnels, in or near villages, it’s a network of tens of kilometers of regional tunnels that extend and connect the Beirut area (Hezbollah’s central headquarters) and the Beqaa area (Hezbollah’s logistical operational rear base) to southern Lebanon (which is divided into two staging areas named by Hezbollah "the lines of defense"). We call this inter-regional tunnel network "Hezbollah's Land of the Tunnels." Various reports indicate that in the late 1980s, and even more so after the Second Lebanon War (2006), North Korean advisors significantly assisted Hezbollah's tunnel project (regarding Hezbollah's history of interaction with North Korea, see appendix A). Hezbollah, inspired and supported by the Iranians, saw North Korea as a professional authority on the subject of tunneling, based on the extensive North Korean experience that had accumulated in building tunnels for military use since the 1950s (regarding the North Korean tunnels, see appendix B.) Hezbollah's model is the same as the North Korean model: tunnels in which hundreds of combatants, fully equipped, can pass stealthily and rapidly underground. -

Saint Sharbel from His Contemporaries to Our Era

Sharbelogy-11 Saint Sharbel From his Contemporaries To our Era Prepared by: Father Hanna Skandar Published by: Our Lady of Fortress-Menjez-Akkar Tel: 06/855351 Web: www. saint-charbel.com & www. menjez.com E-mail: [email protected] Lebanon - 2009 Sharbel ... Crazy by God Sharbel crazy by God! Yes! Because he heard the word of Christ and lived it literally ... Christ said: He who loves his father, his mother, his brothers and sisters more than me, he doesn't deserve to be my disciple... Sharbel, therefore, considered that Christ is the beloved one, so he was attracted to Him, and he became crazy by Him ... until the end... If only we take seriously the word of Christ in our lives ... changing our lives radically for the better and thus taking part to improve the lives of our society, so that its people live the moral values, and the spirit of Christianity literally and with accuracy. Thus we contribute to building a better society, and God remains always our only goal. 05/01/2007 Bishop George Abou Jaoude Archbishop of the Maronite Diocese of Tripoli. Introduction This book is a popular version, without footnotes to facilitate the understanding to the reader. I have mentioned the name of the witness only when the speaker talks in the first-person. If you wish to identify the source of the information, you have either to read the book of: “Saint Sharbel ... as his contemporaries witnessed "-Sharbelogy-7 - To be found in the libraries, or obtained on the Internet in our website www.saint-Charbel.com.