Crossing the Lines: Graphic (Life) Narratives and Co-Laborative Political Transformations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trans & Intersex Resource List

Trans & Intersex Resource List www.transyouth.com Last modified: 7/2009 Quick Reference SAN FRANCISCO & BAY AREA ORGANIZATIONS & SUPPORT SERVICES – page 1 ♦ Children, Youth, Families, & School – page 1 ♦ Health Care & Housing Services – page 4 ♦ Legal, Policy, Advocacy, & Employment – page 9 ♦ Community Empowerment & Social Support – page 11 ADDITIONAL REGIONAL ORGANIZATIONS OUTSIDE THE SF/BAY AREA (by State) – page 14 NATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS – page 19 SAN FRANCISCO & BAY AREA ORGANIZATIONS & SUPPORT SERVICES Children, Youth, Families, & School Ally Action 106 San Pablo Towne Center, PMB #319, San Pablo, CA 94806 (925) 685-5480 www.allyaction.org Contact Person: Julie Lienert (Executive Director) Ally Action educates and engages people to create school communities are safe and inclusive for all, regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity/expression. Ally Action provides comprehensive approaches to eliminating anti-LGBT bias and violence in local school communities by offering training, resources and on-going services that engage local school community members to make a positive difference in each other's lives. Bay Area Young Positives (Bay Positives) 701 Oak Street, San Francisco, CA 94117 (415) 487-1616 www.baypositives.org Contact Person: Curtis Moore (Executive Director) Bay Area Young Positives (BAY Positives) helps young people (26 and under) with HIV/AIDS to live longer, happier, healthier, more productive, and quality-filled lives. The goals of BAY Positives are to work with individual HIV positive young people to: Decrease their sense of isolation, reduce their self-destructive behavior, and advocate for themselves in the complicated HIV/AIDS care system. BAY Positives delivers an array of counseling, case management, and other support, as well as links to other San Francisco youth agencies. -

Redalyc."Mira, Yo Soy Boricua Y Estoy Aquí": Rafa Negrón's Pan Dulce and the Queer Sonic Latinaje of San Francis

Centro Journal ISSN: 1538-6279 [email protected] The City University of New York Estados Unidos Roque Ramírez, Horacio N. "Mira, yo soy boricua y estoy aquí": Rafa Negrón's Pan Dulce and the queer sonic latinaje of San Francisco Centro Journal, vol. XIX, núm. 1, 2007, pp. 274-313 The City University of New York New York, Estados Unidos Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=37719114 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative RoqueRamírez(v6).qxd 6/3/07 4:09 PM Page 274 Figure 8: MTF transgender performer Alejandra. Unless other wise noted all images are “Untitled” from the series Yo Soy Lo Prohibido, 1996 (originals: Type C color prints). Copyright Patrick “Pato” Hebert. Reprinted, by permission, from Patrick “Pato” Hebert. RoqueRamírez(v6).qxd 6/3/07 4:09 PM Page 275 CENTRO Journal Volume7 xix Number 1 spring 2007 ‘Mira, yo soy boricua y estoy aquí’: Rafa Negrón’s Pan Dulce and the queer sonic latinaje of San Francisco HORACIO N. ROQUE RAMÍREZ ABSTRACT For a little more than eight months in 1996–1997, Calirican Rafa Negrón promoted his queer Latino nightclub “Pan Dulce” in San Francisco. A concoction of multiple genders, sexualities, and aesthetic styles, Pan Dulce created an opportunity for making urban space and claiming visibilities and identities among queer Latinas and Latinos through music, performance, and dance. -

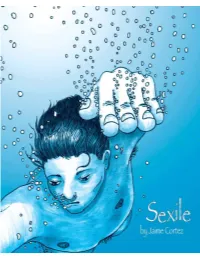

Sexile/Sexilio, De Jaime Cortez

Máster Universitario en Estudios de Género y Políticas de Igualdad HISTORIAS DE VIDA TRANS DESDE EL SEXILIO: SEXILE/SEXILIO, DE JAIME CORTEZ Trabajo realizado por Paula Candelaria Galván Arbelo TRABAJO DE FIN DE MÁSTER Bajo la dirección de PROF. D. JOSE ANTONIO RAMOS ARTEAGA UNIVERSIDAD DE LA LAGUNA Facultad de Humanidades Curso 2019/2020 Convocatoria de septiembre Índice Resumen ........................................................................................................................... 3 Abstract ............................................................................................................................ 3 1. Introducción ............................................................................................................ 4 2. Contexto sociopolítico y prácticas de represión institucional hacia las comunidades LGTBIQ+ en la Cuba castrista ................................................................................. 9 3. Análisis de la obra .................................................................................................. 22 3.1. El éxodo de Mariel ........................................................................................... 29 3.2. La feminización del cuerpo y la posterior labor activista de Adela Vázquez ........ 33 3.3. La crisis del SIDA ............................................................................................ 35 4. Conclusiones finales ............................................................................................... 42 Bibliografía -

BEST PRACTICES for SERVING LGBTQ STUDENTS a Teaching Tolerance Guide TEACHING TOLERANCE APPENDIX a the LGBTQ LIBRARY Books and Films for You and Your Classroom

APPENDIX BEST PRACTICES FOR SERVING LGBTQ STUDENTS A Teaching Tolerance Guide TEACHING TOLERANCE APPENDIX A THE LGBTQ LIBRARY Books and Films for You and Your Classroom This list of books and films—with options for Annie’s Plaid Shirt students of all ages and reading levels—offers by Stacy B. Davids a good starting place for educators who need Annie’s mom demands her daughter wear to diversify their curricula and classroom li- a dress to her uncle’s wedding. But Annie is braries. And, because adults need windows miserable and feels weird wearing dresses. and mirrors too, the list includes profession- So she has a better idea. This book will en- al development options that can broaden courage students to consider gender norms your understanding of LGBTQ history and and possibly rethink the boundaries of per- lived experiences. sonal expression. Gay & Lesbian History for Kids: The Cen- tury-Long Struggle for LGBT Rights Note: This is intended as a resource, and by Jerome Pohlen all books were chosen for their reported This interactive book—complete with 21 value in providing diverse perspectives activities for kids—highlights LGBTQ indi- and representation of LGBTQ characters. viduals who shaped world history. But Teaching Tolerance has not read ev- ery book in this catalogue; educators Heather Has Two Mommies should vet any chosen books carefully by Lesléa Newman before using them in the classroom. This updated version of the 1989 book of the same name simply and beautifully illus- trates the diverse range of families young ELEMENTARY SCHOOL readers can have and appreciate. -

Representations of Queer Women of Colour in Contemporary Fiction and Graphic Narratives

ORBIT - Online Repository of Birkbeck Institutional Theses Enabling Open Access to Birkbecks Research Degree output Misdirection : representations of queer women of colour in contemporary fiction and graphic narratives http://bbktheses.da.ulcc.ac.uk/196/ Version: Full Version Citation: Earle, Monalesia (2016) Misdirection : representations of queer women of colour in contemporary fiction and graphic narratives. PhD thesis, Birkbeck, University of London. c 2016 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copyright law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit guide Contact: email Misdirection: Representations of Queer Women of Colour in Contemporary Fiction and Graphic Narratives Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Birkbeck Monalesia Earle Birkbeck, University of London 1 Declaration I, Monalesia Earle, declare that this thesis is all my own work. Signed declaration _________________________________ Date __________________________ 2 Abstract This thesis examines the notion of misdirection and queer women of colour representation in contemporary fiction and graphic narratives. Its aim is to analyse the gaps in discursive debates that overlook or minimise queer women of colour subjectivities. In so doing, it develops new lines of critical enquiry that bring into dialogue recurring themes of race, gender, class, homophobia, sexual violence and trauma. The thesis discusses five texts published between 1982 and 2008, opening up critical pathways into the interrogation of intersecting oppressions that limit and/or completely eradicate the voices and realities of queer women of colour. Developing the notion of misdirection as both an analytical and performative tool that problematises ‘difference’, this thesis shows that through contemporary framings, queer women of colour representation in literary fiction and comics/graphic narratives can be liberated from the cultural hegemony of white- centric paradigms. -

Review Essay: Evangelization and Cultural Identities in Spanish America (1598-Present)

Review Essay: Evangelization and Cultural Identities in Spanish America (1598-Present) Andrango-Walker, Catalina. El símbolo católico indiano (1598) de Luís Jerónimo de Oré. Saberes coloniales y los problemas de la evangelización en la región andina. Madrid: Iberoamericana/Vervuert, 2018. 237 pp. ISBN 9788-4169-2290-1. Nogar, Anna M. Quill and Cross in the Borderlands: Sor María de Ágreda and the Lady in Blue, 1628 to the Present. Notre Dame, IN: U of Notre Dame P, 2018. ix-xv + 457 pp. ISBN 9780-2681-0213-5. In El símbolo católico indiano (1598) de Luís Jerónimo de Oré. Saberes coloniales y los problemas de la evangelización en la región andina (2018), Catalina Andrango-Walker establishes Oré’s Símbolo as an overlooked yet valuable resource on early modern viceregal Perú. In four chapters, she considers the Símbolo as a response to the Third Lima Council (1582-1583) and José de Acosta’s Historia natural y moral (1590), and its intertextuality with other contemporary and classical texts. In addition, she examines Oré’s didactic strategies for converting the natives, pointing out how he uses this evangelical pedagogy to covertly criticize aspects of viceregal political and ecclesiastic administration. But whereas Latin Americanists have understood the Símbolo as merely another catechization manual, Andrango-Walker rescues its contributions to pre-Hispanic and colonial Andean history and geography, largely by underscoring Oré’s claim that evangelization efforts in Perú were ineffective due to administrative corruption and bureaucratic inefficacy rather than the natives’ alleged savagery and lack of civilization. Consequently, Andrango-Walker’s analysis reveals more broadly “la identidad del criollo en pleno proceso de construcción” (194). -

Intersecciones Entre Cine Documental Y Archivos Queer: Notas a Propósito De Sexilio

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Master's Theses University of Connecticut Graduate School 5-10-2020 Intersecciones entre Cine Documental y Archivos Queer: Notas a Propósito de Sexilio. LAZARO J. GONZALEZ University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/gs_theses Recommended Citation GONZALEZ, LAZARO J., "Intersecciones entre Cine Documental y Archivos Queer: Notas a Propósito de Sexilio." (2020). Master's Theses. 1479. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/gs_theses/1479 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Connecticut Graduate School at OpenCommons@UConn. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of OpenCommons@UConn. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Intersecciones entre cine documental y archivos queer: notas a propósito de Sexilio. Lázaro González González B. A, University of Havana, 2014 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts At the University of Connecticut 2020 Copyright by Lázaro González González [2020] ii APPROVAL PAGE Master of Arts Thesis Intersecciones entre cine documental y archivos queer: notas a propósito de Sexilio. Presented by Lázaro González González, B.A. Major Advisor Dr. Miguel Gomes Associate advisor (Director)_____________________________________________________ Dra. Jacqueline Loss Associate Advisor Dra. Rosa Helena Chinchilla Associate Advisor Dra. Ana María Díaz-Marcos University of Connecticut 2020 iii Agradecimientos Agradezco particularmente a todos los profesores del Departamento de Literaturas, Culturas y Lenguajes de la Universidad de Connecticut por todo su apoyo durante estos dos intensos años de vida académica. -

Impossibly Here, Impossibly Queer: Citizenship, Sexuality, and Gay Chicano Fiction

MIAMI UNIVERSITY The Graduate School Certificate for Approving the Dissertation We hereby approve the Dissertation of José A. de la Garza Valenzuela Candidate for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy ______________________________________ Dr. Stefanie K. Dunning, Co-Director ______________________________________ Dr. Julie A. Minich, Co-Director ______________________________________ Dr. Madelyn Detloff, Reader ______________________________________ Dr. Anita Mannur, Reader ______________________________________ Dr. Gaile Pohlhaus, Jr. Graduate School Representative ABSTRACT IMPOSSIBLY HERE, IMPOSSIBLY QUEER: CITIZENSHIP, SEXUALITY, AND GAY CHICANO FICTION by José A. de la Garza Valenzuela Advocacy for the rights of undocumented migrants and members of the LGBT community have emerged as defining social justice movements in the early 21st century in the U.S. In both movements, citizenship has been invoked as a legal category of particular concern, the first advocating for a pathway to documented status leading to citizenship and the second asserting that denying same-sex couples the right to marry renders gay and lesbian communities second-class citizens. This dissertation uses the contemporary deployment of citizenship as point of departure, arguing against understandings of the category as defined by inclusivity. Exclusion, I argue, is a defining trait of citizenship, one that allows us to reorient considerations of cultural and legal membership in the U.S. Rather than considering citizenship as the site where disenfranchisement is resolved, I use the failures of citizenship as an analytical point of departure guided not by an interest in citizenship as a site of justice, but instead as a legal institution that insists on the impossibility of non- normative identity categories. In doing so, I turn my attention to legal, historical, and/or literary moments where our commitment to citizenship has failed to ascertain rights for queer and migrant communities. -

A Report for the HIV Prevention Section of the San Francisco Department of Public Health

A Report for the HIV Prevention Section of the San Francisco Department of Public Health Prepared by Jorge Sánchez and Rafael Díaz Cause Data Collective October 2009 Table of Contents Latino Action Plan Executive Summary.....................................................................1-17 Findings and Recommendations ................................................. 3 Report Components and Project Process.................................. 11 Epidemiological Context ............................................................ 14 Chapter 1/ Double Edges of Freedom.......................................18-32 Chapter 2/ Qualitative Analysis of Focus Group Data ...............33-73 Spanish Speaking Group – ages 23-35 ..................................... 34 Spanish Speaking Group – ages 36 .......................................... 45 English Speaking Group– ages 18-35 ....................................... 52 English Speaking Group – ages 36+ ......................................... 63 Similarities & Contrasts.............................................................. 71 Chapter 3/ Demographic Profile ................................................74-82 Chapter 4/ Nuestras Voces Quantitative Findings.....................83-93 Chapter 5/ Lessons From Providers........................................94-112 Chapter 6/ Literature Review: Latino Gay Men & HIV ...........113-132 Literature Review References.................................................. 130 Postscript...............................................................................133-135 -

A Link to Sexile by Jaime Cortez

CREDITS: Written, illustrated and lettered by Jaime Cortez From biographical interviews with Adela Vazquez Translation by Omar Baños with consultation by Adela Vazquez Edited by Pato Hebert SHOUT OUTS AND LOVE: • Adela Vazquez for living this amazing story and then sharing it. • Pato Hebert for shepherding Sexile through to completion and for the world-class love, support and laughs. Post fierce indeed, Duckman. • George Ayala for the leadership, vision and windows of opportunity. • AIDS Project Los Angeles and Gay Men’s Health Crisis for the willingness to try something scary. • Jose Marquez for initiating the Sexile website at KQED, from which this comic sprung forth. CRITICISM, TECHNICAL TIPS BY: Tisa Bryant, Pato Hebert, Claire Light, Jose Marquez, Marcia Ochoa, Sarah Patterson, Carolina Ponce de Leon, Lori Wood, Matt Young, Peta-Gay Pottinger. INSPIRATION BY: Yoshitoshi, Aubrey Beardsley, Neil Gaiman, Jean Genet, Jae Lee, Frank Miller, Jose Guadalupe Posada, Joe Sacco, David Wojnarowicz, and the diasporic folk of the Proyecto Village. Hope you guys like the new baby. I SAMPLED: Yes, I am a hip hop baby that way. • The fetus image (page 4) was based on a photo from Lennart Nillson’s Drama of Life Before Birth. • The drawing of outrageous queens at a café table (page 19) was based on a detail from Paul Cadmus’ 1952 egg tempra painting Bar Italia. • The photo of our bloodied, beat down protaganist (page 25) is based on one of Carolyn Cole’s 2003 photos from a Haitian food riot. • The drawings of the refugees crowded onto the boat Lynn Marie (page 33), the boat docking (page 36), and the Point Trumbo Air Force Base hangar (page 37) were based on images found on the Cuban Information Archives website (http://cuban-exile.com). -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title "Our Bodies, Our Souls: Creating a Trans Latina Archive Through Critical Autoethnography" Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4vj5r224 Author Rodriguez, Claudia L Publication Date 2020 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Our Bodies, Our Souls: Creating a Trans Latina Archive Through Critical Autoethnography A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Chicana and Chicano Studies by Claudia Lizet Rodriguez 2020 © Copyright by Claudia Lizet Rodriguez 2020 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Our Bodies, Our Souls: Creating a Trans Latina Archive Through Critical Autoethnography by Claudia Lizet Rodriguez Master of Arts in Chicana and Chicano Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2020 Professor Alicia Gaspar de Alba, Committee Chair Transgender Latina immigrants occupy a limited and unfavorable space in the popular imagination. Essentialist and reductive master narratives erase the richness and complexity of this community. General representations of trans Latinas fixate on gender and racial violence, and victimization. Rarely do these representations focus on experiences that embody trans Latinas’ everyday lives, struggles, love, aspirations and acts of resilience. The need for alternative discourses for trans Latina immigrants is especially pressing now under the Trump administration when immigrants are depicted as economic and cultural threats ii to the “Great American” way of life, and immigrant families are torn apart as parents get deported en masse and their children abandoned to an uncertain future. There are very few published works written by transgender Latina immigrants. -

BEST PRACTICES for SERVING LGBTQ STUDENTS a Teaching Tolerance Guide TEACHING TOLERANCE APPENDIX a the LGBTQ LIBRARY Books and Films for You and Your Classroom

APPENDIX BEST PRACTICES FOR SERVING LGBTQ STUDENTS A Teaching Tolerance Guide TEACHING TOLERANCE APPENDIX A THE LGBTQ LIBRARY Books and Films for You and Your Classroom This list of books and films—with options for Annie’s Plaid Shirt students of all ages and reading levels—offers by Stacy B. Davids a good starting place for educators who need Annie’s mom demands her daughter wear to diversify their curricula and classroom li- a dress to her uncle’s wedding. But Annie is braries. And, because adults need windows miserable, and feels weird wearing dress- and mirrors too, the list includes profession- es. So she has a better idea. This book will al development options that can broaden encourage students to consider gender your understanding of LGBTQ history and norms, and possibly rethink the boundaries lived experiences. of personal expression. Gay & Lesbian History for Kids: The Cen- tury-Long Struggle for LGBT Rights Note: This is intended as a resource, and by Jerome Pohlen all books were chosen for their reported This interactive book—complete with 21 value in providing diverse perspectives activities for kids—highlights LGBTQ indi- and representation of LGBTQ characters. viduals who shaped world history. But Teaching Tolerance has not read ev- ery book in this catalogue; educators Heather Has Two Mommies should vet any chosen books carefully by Lesléa Newman before using them in the classroom. This updated version of the 1989 book of the same name simply and beautifully illus- trates the diverse range of families young ELEMENTARY SCHOOL readers can have and appreciate. I Am Jazz And Tango Makes Three by Jazz Jennings and Jessica Herthel by Justin Richardson and Peter Parnell This book—based on Jazz’s real-life experi- This true story about two penguins, Roy ence—offers a simple, clear window into the and Silo, at the Central Park Zoo who cre- life of a transgender girl who knew her true ated a nontraditional family offers a heart- self from a young age.