A Report for the HIV Prevention Section of the San Francisco Department of Public Health

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AIDS History Project •fl Ephemera Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt1t1nd055 Online items available Finding Aid to the AIDS History Project — Ephemera Collection, 1973, 1981-2002MSS.2000.31 Finding Aid written by Shelley Carr Funding for processing this collection was provided by The National Historical Publications and Records Commission. University of California, San Francisco Archives & Special Collections © 2018 530 Parnassus Ave Room 524 San Francisco, CA 94143-0840 [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucsf.edu/collections/archives Finding Aid to the AIDS History MSS.2000.31 1 Project — Ephemera Collection, 1973, 1981-2002MSS.2000.31 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: University of California, San Francisco Archives & Special Collections Title: AIDS history project — ephemera collection Creator: University of California, San Francisco. Library. Archives and Special Collections Identifier/Call Number: MSS.2000.31 Physical Description: 7 Linear Feet5 boxes, 1 takeout box, 1 map box, 9 oversize folders Date (inclusive): 1973, 1981-2002 Abstract: This is an artificial collection assembled from a number of different donations of ephemeral materials, acquired by the Library as a part of the AIDS History Project. Paper based materials include flyers, brochures, wallet cards, and posters from the US and international sources. Some artifacts are also included, such as condoms and condom holders. All deal with the medical and/or social aspects of AIDS and HIV, with a focus on prevention and on addressing misconceptions about the disease. Language of Material: Most of the collection materials are in English, with some materials in other languages. For current information on the location of these materials, please consult the library's online catalog: http://www.library.ucsf.edu/ . -

Trans & Intersex Resource List

Trans & Intersex Resource List www.transyouth.com Last modified: 7/2009 Quick Reference SAN FRANCISCO & BAY AREA ORGANIZATIONS & SUPPORT SERVICES – page 1 ♦ Children, Youth, Families, & School – page 1 ♦ Health Care & Housing Services – page 4 ♦ Legal, Policy, Advocacy, & Employment – page 9 ♦ Community Empowerment & Social Support – page 11 ADDITIONAL REGIONAL ORGANIZATIONS OUTSIDE THE SF/BAY AREA (by State) – page 14 NATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS – page 19 SAN FRANCISCO & BAY AREA ORGANIZATIONS & SUPPORT SERVICES Children, Youth, Families, & School Ally Action 106 San Pablo Towne Center, PMB #319, San Pablo, CA 94806 (925) 685-5480 www.allyaction.org Contact Person: Julie Lienert (Executive Director) Ally Action educates and engages people to create school communities are safe and inclusive for all, regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity/expression. Ally Action provides comprehensive approaches to eliminating anti-LGBT bias and violence in local school communities by offering training, resources and on-going services that engage local school community members to make a positive difference in each other's lives. Bay Area Young Positives (Bay Positives) 701 Oak Street, San Francisco, CA 94117 (415) 487-1616 www.baypositives.org Contact Person: Curtis Moore (Executive Director) Bay Area Young Positives (BAY Positives) helps young people (26 and under) with HIV/AIDS to live longer, happier, healthier, more productive, and quality-filled lives. The goals of BAY Positives are to work with individual HIV positive young people to: Decrease their sense of isolation, reduce their self-destructive behavior, and advocate for themselves in the complicated HIV/AIDS care system. BAY Positives delivers an array of counseling, case management, and other support, as well as links to other San Francisco youth agencies. -

Redalyc."Mira, Yo Soy Boricua Y Estoy Aquí": Rafa Negrón's Pan Dulce and the Queer Sonic Latinaje of San Francis

Centro Journal ISSN: 1538-6279 [email protected] The City University of New York Estados Unidos Roque Ramírez, Horacio N. "Mira, yo soy boricua y estoy aquí": Rafa Negrón's Pan Dulce and the queer sonic latinaje of San Francisco Centro Journal, vol. XIX, núm. 1, 2007, pp. 274-313 The City University of New York New York, Estados Unidos Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=37719114 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative RoqueRamírez(v6).qxd 6/3/07 4:09 PM Page 274 Figure 8: MTF transgender performer Alejandra. Unless other wise noted all images are “Untitled” from the series Yo Soy Lo Prohibido, 1996 (originals: Type C color prints). Copyright Patrick “Pato” Hebert. Reprinted, by permission, from Patrick “Pato” Hebert. RoqueRamírez(v6).qxd 6/3/07 4:09 PM Page 275 CENTRO Journal Volume7 xix Number 1 spring 2007 ‘Mira, yo soy boricua y estoy aquí’: Rafa Negrón’s Pan Dulce and the queer sonic latinaje of San Francisco HORACIO N. ROQUE RAMÍREZ ABSTRACT For a little more than eight months in 1996–1997, Calirican Rafa Negrón promoted his queer Latino nightclub “Pan Dulce” in San Francisco. A concoction of multiple genders, sexualities, and aesthetic styles, Pan Dulce created an opportunity for making urban space and claiming visibilities and identities among queer Latinas and Latinos through music, performance, and dance. -

Pearl Boy Vibrator

Pearl Boy Vibrator This is our biggest selling model in the vibrators. It is a multi-speed vibrator with rabbit clitoris stimulator and rotating pearls for internal stimulation. Ensuring your ultimate PLEASURE! The most popular and famous “orgasm machine” on the market for its price range is the Pearl Boy. Manufactured in Japan, this vibrator has durability and quality written all over it. Its functionality is very diverse and has a few functions available, making it a real favourite. The device is quiet, powerful and smooth, filling the top qualities looked for by women. The Pearl Boy has 2 slide controllers allowing you to increase or decrease intensity for your own personal pleasure. One is for the pearl rotation of the vibrators shaft giving you a stimulating internal sensation! The movement of the pearls rotating inside is very pleasurable, and for some, very stimulating for the G-Spot. The other slide control is for the clit tickler. The tickler on the Pearl Boy is purrrrfection! They have mastered the right balance of firmness in the V-shaped tickler which also, unlike many others, vibrates slightly from side to side giving you double the stimulation while speed adjustable. Due to the side to side motion of the tickler, this makes the Pearl Boy also an excellent vibrator to be used with a partner, giving them more ability to please you with this toy! Operates on 3 AA Batteries. Not Included Companion Products LUBE AA Batteries Helmet Hammer ©Intimate Whispers 2014-17 Gigi – The Rechargeable Silicone Toy When your GiGi arrives you will find it to be luxuriously packaged! The outside packaging will match the colour of the product inside. -

STOP AIDS Project Records, 1985-2011M1463

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8v125bx Online items available Guide to the STOP AIDS Project records, 1985-2011M1463 Laura Williams and Rebecca McNulty, October 2012 Department of Special Collections and University Archives October 2012; updated March 2019 Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford 94305-6064 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Guide to the STOP AIDS Project M1463 1 records, 1985-2011M1463 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Title: STOP AIDS Project records, creator: STOP AIDS Project Identifier/Call Number: M1463 Physical Description: 373.25 Linear Feet(443 manuscript boxes; 136 record storage boxes; 9 flat boxes; 3 card boxes; 21 map folders and 10 rolls) Date (inclusive): 1985-2011 Special Collections and University Archives materials are stored offsite and must be paged 36-48 hours in advance. For more information on paging collections, see the department's website: http://library.stanford.edu/depts/spc/spc.html. Abstract: Founded in 1984 (non-profit status attained, 1985), the STOP AIDS Project is a community-based organization dedicated to the prevention of HIV transmission among gay, bisexual and transgender men in San Francisco. Throughout its history, the STOP AIDS Project has been overwhelmingly successful in meeting its goal of reducing HIV transmission rates within the San Francisco Gay community through innovative outreach and education programs. The STOP AIDS Project has also served as a model for community-based HIV/AIDS education and support, both across the nation and around the world. The STOP AIDS Project records are comprised of behavioral risk assessment surveys; social marketing campaign materials, including HIV/AIDS prevention posters and flyers; community outreach and workshop materials; volunteer training materials; correspondence; grant proposals; fund development materials; administrative records; photographs; audio and video recordings; and computer files. -

Marketing Safe Sex: the Politics of Sexuality, Race and Class in San Francisco, 1983 - 1991

Marketing Safe Sex: The Politics of Sexuality, Race and Class in San Francisco, 1983 - 1991 Jennifer Brier Great Cities Institute College of Urban Planning and Public Affairs University of Illinois at Chicago Great Cities Institute Publication Number: GCP-06-06 A Great Cities Institute Working Paper May 2006 The Great Cities Institute The Great Cities Institute is an interdisciplinary, applied urban research unit within the College of Urban Planning and Public Affairs at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC). Its mission is to create, disseminate, and apply interdisciplinary knowledge on urban areas. Faculty from UIC and elsewhere work collaboratively on urban issues through interdisciplinary research, outreach and education projects. About the Author Jennifer Brier is Assistant Professor of Gender and Women’s Studies and History in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences at the University of Illinois at Chicago. She was a GCI Faculty Scholar during the 2005 – 2006 academic year. She may be reached at [email protected]. Great Cities Institute Publication Number: GCP-06-06 The views expressed in this report represent those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the Great Cities Institute or the University of Illinois at Chicago. This is a working paper that represents research in progress. Inclusion here does not preclude final preparation for publication elsewhere. Great Cities Institute (MC 107) College of Urban Planning and Public Affairs University of Illinois at Chicago 412 S. Peoria Street, Suite 400 Chicago IL 60607-7067 -

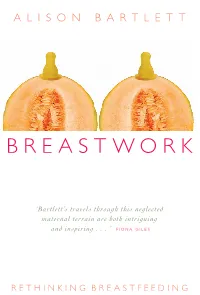

B R E a S T W O

BREASTWORK ALISON BARTLETT ‘BREASTWORK is a beautifully written and accessible guide to the many unexplored cultural meanings of breastfeeding in contemporary society. Of all our bodily functions, lactation is perhaps the most mysterious and least understood. Promoted primarily in terms of its nutritional benefi ts to babies, its place – or lack of it – in Western culture remains virtually unexplored. Bartlett’s travels through this neglected maternal terrain are both intriguing and inspiring, as she shows how breastfeeding can be a transformative act, rather than a moral duty. Looking at breastfeeding in relation to medicine, the media, sexuality, maternity and race, Bartlett’s study BREASTWORK provides a uniquely comprehensive overview of the ways in which we represent breastfeeding to ourselves and the many arbitrary limits we place around it. BREASTWORK makes a fresh, thoughtful and important contribution BARTLETT to the new area of breastfeeding and cultural studies. It is essential reading for ‘Bartlett’s travels through this neglected all students of the body, whether in the health professions, the social sciences, maternal terrain are both intriguing or gender and cultural studies – and for and inspiring . ’ F IONA GILES all mothers who have pondered the secrets of their own breastly intelligence.’ FIONA GILES author of Fresh Milk: The Secret Life of Breasts UNSW PRESS ISBN 0-86840-969-3 � UNSW RETHINKIN G BREASTFEEDING 9 780868 409696 � PRESS BreastfeedingCover2print.indd 1 29/7/05 11:44:52 AM BreastWork04 28/7/05 11:30 AM Page i BREASTWORK ALISON BARTLETT is the Director of the Centre for Women’s Studies at the University of Western Australia. -

Sexile/Sexilio, De Jaime Cortez

Máster Universitario en Estudios de Género y Políticas de Igualdad HISTORIAS DE VIDA TRANS DESDE EL SEXILIO: SEXILE/SEXILIO, DE JAIME CORTEZ Trabajo realizado por Paula Candelaria Galván Arbelo TRABAJO DE FIN DE MÁSTER Bajo la dirección de PROF. D. JOSE ANTONIO RAMOS ARTEAGA UNIVERSIDAD DE LA LAGUNA Facultad de Humanidades Curso 2019/2020 Convocatoria de septiembre Índice Resumen ........................................................................................................................... 3 Abstract ............................................................................................................................ 3 1. Introducción ............................................................................................................ 4 2. Contexto sociopolítico y prácticas de represión institucional hacia las comunidades LGTBIQ+ en la Cuba castrista ................................................................................. 9 3. Análisis de la obra .................................................................................................. 22 3.1. El éxodo de Mariel ........................................................................................... 29 3.2. La feminización del cuerpo y la posterior labor activista de Adela Vázquez ........ 33 3.3. La crisis del SIDA ............................................................................................ 35 4. Conclusiones finales ............................................................................................... 42 Bibliografía -

Court Green Publications

Columbia College Chicago Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago Court Green Publications 3-1-2013 Court Green: Dossier: Sex Columbia College Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/courtgreen Part of the Poetry Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Columbia College Chicago, "Court Green: Dossier: Sex" (2013). Court Green. 10. https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/courtgreen/10 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. It has been accepted for inclusion in Court Green by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Read good poetry!” —William Carlos Williams COURT GREEN 10 COURT 10 EDITORS Tony Trigilio and David Trinidad MANAGING EDITOR Cora Jacobs SENIOR EDITORIAL ASSISTANT Jessica Dyer EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS S’Marie Clay, Abby Hagler, Jordan Hill, and Eugene Sampson Court Green is published annually in association with Columbia College Chicago, Department of English. Our thanks to Ken Daley, Chair, Department of English; Deborah H. Holdstein, Dean, School of Liberal Arts and Sciences; Louise Love, Interim Provost; and Dr. Warrick Carter, President of Columbia College Chicago. Our submission period is March 1-June 30 of each year. Please send no more than five pages of poetry. We will respond by August 31. Each issue features a dossier on a particular theme; a call for work for the dossier for Court Green 11 is at the back of this issue. Submissions should be sent to the editors at Court Green, Columbia College Chicago, Department of English, 600 South Michigan Avenue, Chicago, IL 60605. -

VAGINA Vagina, Pussy, Bearded Clam, Vertical Smile, Beaver, Cunt, Trim, Hair Pie, Bearded Ax Wound, Tuna Taco, Fur Burger, Cooch

VAGINA vagina, pussy, bearded clam, vertical smile, beaver, cunt, trim, hair pie, bearded ax wound, tuna taco, fur burger, cooch, cooter, punani, snatch, twat, lovebox, box, poontang, cookie, fuckhole, love canal, flower, nana, pink taco, cat, catcher's mitt, muff, roast beef curtains, the cum dump, chocha, black hole, sperm sucker, fish sandwich, cock warmer, whisker biscuit, carpet, love hole, deep socket, cum craver, cock squeezer, slice of heaven, flesh cavern, the great divide, cherry, tongue depressor, clit slit, hatchet wound, honey pot, quim, meat massager, chacha, stinkhole, black hole of calcutta, cock socket, pink taco, bottomless pit, dead clam, cum crack, twat, rattlesnake canyon, bush, cunny, flaps, fuzz box, fuzzy wuzzy, gash, glory hole, grumble, man in the boat, mud flaps, mound, peach, pink, piss flaps, the fish flap, love rug, vadge, the furry cup, stench-trench, wizard's sleeve, DNA dumpster, tuna town, split dick, bikini bizkit, cock holster, cockpit, snooch, kitty kat, poody tat, grassy knoll, cold cut combo, Jewel box, rosebud, curly curtains, furry furnace, slop hole, velcro love triangle, nether lips, where Uncle's doodle goes, altar of love, cupid's cupboard, bird's nest, bucket, cock-chafer, love glove, serpent socket, spunk-pot, hairy doughnut, fun hatch, spasm chasm, red lane, stinky speedway, bacon hole, belly entrance, nookie, sugar basin, sweet briar, breakfast of champions, wookie, fish mitten, fuckpocket, hump hole, pink circle, silk igloo, scrambled eggs between the legs, black oak, Republic of Labia, -

Sex and Diabetes: a Thematic Analysis of Gay and Bisexual Men's

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Aston Publications Explorer Jowett et al (2012) Sex and Diabetes Sex and Diabetes: A Thematic Analysis of Gay and Bisexual Men’s Accounts Adam Jowett1, Elizabeth Peel and Rachel L. Shaw Please cite the published version of this paper available from the publisher’s website: http://hpq.sagepub.com/content/17/3/409.abstract Jowett, A., Peel, E., & Shaw, R.L. (2012). Sex and diabetes : a thematic analysis of gay and bisexual men's accounts. Journal of health psychology, 17 (3), 409-418. DOI: 10.1177/1359105311412838 ABSTRACT Around 50 per cent of men with diabetes experience erectile dysfunction. Much of the literature focuses on quality of life measures with heterosexual men in monogamous relationships. This study explores gay and bisexual men’s experiences of sex and diabetes. Thirteen interviews were analysed and three themes identified: erectile problems; other ‘physical’ problems; and disclosing diabetes to sexual partners. Findings highlight a range of sexual problems experienced by non-heterosexual men and the significance of the cultural and relational context in which they are situated. The personalized care promised by the UK government should acknowledge the diversity of sexual practices which might be affected by diabetes. Keywords diabetes, diversity, men’s health, qualitative methods, sexual health, sexuality 1 Corresponding author: Dr Adam Jowett, Department of Psychology & Behavioural Sciences, Coventry University, CV1 5FB, UK. Email: [email protected] 1 Jowett et al (2012) Sex and Diabetes INTRODUCTION Diabetes is a group of disorders that interferes with the body’s ability to use glucose in the blood properly and affects over two million people in England alone (Department of Health (DoH), 2010). -

Appearances and Grooming Standards As Sex Discrimination in the Workplace

Catholic University Law Review Volume 56 Issue 1 Fall 2006 Article 9 2006 Appearances and Grooming Standards as Sex Discrimination in the Workplace Allison T. Steinle Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview Recommended Citation Allison T. Steinle, Appearances and Grooming Standards as Sex Discrimination in the Workplace, 56 Cath. U. L. Rev. 261 (2007). Available at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview/vol56/iss1/9 This Comments is brought to you for free and open access by CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Catholic University Law Review by an authorized editor of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. APPEARANCE AND GROOMING STANDARDS AS SEX DISCRIMINATION IN THE WORKPLACE Allison T. Steinle' "It is amazing how complete is the delusion that beauty is good- ness."' Since the inception of Title VII's prohibition against employment dis- crimination on the basis of sex,2 women have made remarkable progress in their effort to shatter the ubiquitous glass ceiling3 and achieve parity + J.D. Candidate, 2007, The Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law; A.B., 2004, The University of Michigan. The author would like to thank Professor Jeffrey W. Larroca for his invaluable guidance throughout the writing process and Peggy M. O'Neil for her excellent editing and advice. She also thanks her family and friends for their unending love, support, and patience. 1. LEO TOLSTOY, The Kreutzer Sonata, in THE KREUTZER SONATA AND OTHER STORIEs 85, 100 (Richard F. Gustafson ed., Louise Shanks Maude et al.