Nelson Mandela As Negotiator: What Can We Learn from Him?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete Dissertation

VU Research Portal Itineraries Rousseau, N. 2019 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Rousseau, N. (2019). Itineraries: A return to the archives of the South African truth commission and the limits of counter-revolutionary warfare. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 09. Oct. 2021 VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT Itineraries A return to the archives of the South African truth commission and the limits of counter-revolutionary warfare ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. V. Subramaniam, in het openbaar te verdedigen ten overstaan van de promotiecommissie van de Faculteit der Geesteswetenschappen op woensdag 20 maart 2019 om 15.45 uur in de aula van de universiteit, De Boelelaan 1105 door Nicky Rousseau geboren te Dundee, Zuid-Afrika promotoren: prof.dr. -

Nelson-Mandelas-Legacy.Pdf

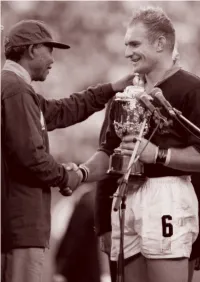

Nelson Mandela’s Legacy What the World Must Learn from One of Our Greatest Leaders By John Carlin ver since Nelson Mandela became president of South Africa after winning his Ecountry’s fi rst democratic elections in April 1994, the national anthem has consisted of two songs spliced—not particularly mellifl uously—together. One is “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika,” or “God Bless Africa,” sung at black protest ral- lies during the forty-six years between the rise and fall of apartheid. The other is “Die Stem,” (“The Call”), the old white anthem, a celebration of the European settlers’ conquest of Africa’s southern tip. It was Mandela’s idea to juxtapose the two, his purpose being to forge from the rival tunes’ discordant notes a powerfully symbolic message of national harmony. Not everyone in Mandela’s party, the African National Congress, was con- vinced when he fi rst proposed the plan. In fact, the entirety of the ANC’s national executive committee initially pushed to scrap “Die Stem” and replace it with “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika.” Mandela won the argument by doing what defi ned his leadership: reconciling generosity with pragmatism, fi nding common ground between humanity’s higher values and the politician’s aspiration to power. The chief task the ANC would have upon taking over government, Mandela reminded his colleagues at the meeting, would be to cement the foundations of the hard-won new democracy. The main threat to peace and stability came from right-wing terrorism. The way to deprive the extremists of popular sup- port, and therefore to disarm them, was by convincing the white population as a whole President Nelson Mandela and that they belonged fully in the ‘new South Francois Pienaar, captain of the Africa,’ that a black-led government would South African Springbok rugby not treat them the way previous white rulers team, after the Rugby World Cup had treated blacks. -

Potential of the Implementation of Demand-Side Management at the Theunissen-Brandfort Pumps Feeder

POTENTIAL OF THE IMPLEMENTATION OF DEMAND-SIDE MANAGEMENT AT THE THEUNISSEN-BRANDFORT PUMPS FEEDER by KHOTSOFALO CLEMENT MOTLOHI Dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree MAGISTER TECHNOLOGIAE: ENGINEERING: ELECTRICAL In the Faculty of Engineering, Information & Communication Technology: School of Electrical & Computer Systems Engineering At the Central University of Technology, Free State Supervisor: Mr L Moji, MSc. (Eng) Co- supervisor: Prof. LJ Grobler, PhD (Eng), CEM BLOEMFONTEIN NOVEMBER 2006 i PDF created with pdfFactory trial version www.pdffactory.com ii DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENT WORK I, KHOTSOFALO CLEMENT MOTLOHI, hereby declare that this research project submitted for the degree MAGISTER TECHNOLOGIAE: ENGINEERING: ELECTRICAL, is my own independent work that has not been submitted before to any institution by me or anyone else as part of any qualification. Only the measured results were physically performed by TSI, under my supervision (refer to Appendix I). _______________________________ _______________________ SIGNATURE OF STUDENT DATE PDF created with pdfFactory trial version www.pdffactory.com iii Acknowledgement My interest in the energy management study concept actually started while reading Eskom’s journals and technical bulletins about efficient-energy utilisation and its importance. First of all I would like to thank ALMIGHTY GOD for making me believe in MYSELF and giving me courage throughout this study. I would also like to thank the following people for making this study possible. I would like to express my sincere gratitude and respect to both my supervisors Mr L Moji and Prof. LJ Grobler who is an expert and master of the energy utilisation concept and also for both their positive criticism and the encouragement they gave me throughout this study. -

Remembrance African Activist Archive Project Documenting

Remembrance African Activist Archive Project Documenting Apartheid: 30 Years of Filming South Africa By Peter Davis During April 2004 and beyond we were constantly reminded that this is the tenth anniversary of the first democratic all-race elections in South Africa. I was shocked by the realization that last year also marked the thirtieth anniversary of my first visit to that country, of my first experience with apartheid. After that first trip in 1974 as part of an African tour I was doing for the American NGO, Care, I was to devote a large part of my working life to the anti-apartheid struggle. For those of us who were involved in that struggle, it was such an everyday part of life that it is hard to grasp that there is already a generation out there that does not know the meaning of “apartheid”. The struggle against apartheid took many forms, from protests, strikes, sabotage, defiance, guerrilla warfare within the country to boycotts, bans, United Nations resolutions, rock concerts, and arms and money smuggling and espionage outside. Apartheid, which was institutionalized by the coming to power of the white National Party in 1948, lasted as long as it did, against the condemnation of the world, because it had powerful friends. Chief among these were the United States, which saw a South Africa governed by whites as a useful ally in the Cold War; a Britain whose ruling class had close links with South African capital; and German, French, Israeli and Taiwanese commercial interests that extended even to sales of weapons and nuclear technology to the apartheid regime. -

Searchlight South Africa: a Marxist Journal of Southern African Studies Vol

Searchlight South Africa: a marxist journal of Southern African studies Vol. 2, No. 7 http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.PSAPRCA0009 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Searchlight South Africa: a marxist journal of Southern African studies Vol. 2, No. 7 Alternative title Searchlight South Africa Author/Creator Hirson, Baruch; Trewhela, Paul; Ticktin, Hillel; MacLellan, Brian Date 1991-07 Resource type Journals (Periodicals) Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) Ethiopia, Iraq, Namibia, South Africa Coverage (temporal) -

PRENEGOTIATION Ln SOUTH AFRICA (1985 -1993) a PHASEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS of the TRANSITIONAL NEGOTIATIONS

PRENEGOTIATION lN SOUTH AFRICA (1985 -1993) A PHASEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF THE TRANSITIONAL NEGOTIATIONS BOTHA W. KRUGER Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at the University of Stellenbosch. Supervisor: ProfPierre du Toit March 1998 Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za DECLARATION I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it at any university for a degree. Signature: Date: The fmancial assistance of the Centre for Science Development (HSRC, South Africa) towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at, are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the Centre for Science Development. Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za OPSOMMING Die opvatting bestaan dat die Suid-Afrikaanse oorgangsonderhandelinge geinisieer is deur gebeurtenisse tydens 1990. Hierdie stuC.:ie betwis so 'n opvatting en argumenteer dat 'n noodsaaklike tydperk van informele onderhandeling voor formele kontak bestaan het. Gedurende die voorafgaande tydperk, wat bekend staan as vooronderhandeling, het lede van die Nasionale Party regering en die African National Congress (ANC) gepoog om kommunikasiekanale daar te stel en sodoende die moontlikheid van 'n onderhandelde skikking te ondersoek. Deur van 'n fase-benadering tot onderhandeling gebruik te maak, analiseer hierdie studie die oorgangstydperk met die doel om die struktuur en funksies van Suid-Afrikaanse vooronderhandelinge te bepaal. Die volgende drie onderhandelingsfases word onderskei: onderhande/ing oor onderhandeling, voorlopige onderhande/ing, en substantiewe onderhandeling. Beide fases een en twee word beskou as deel van vooronderhandeling. -

Reflections on Apartheid in South Africa: Perspectives and an Outlook for the Future

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 415 168 SO 028 325 AUTHOR Warnsley, Johnnye R. TITLE Reflections on Apartheid in South Africa: Perspectives and an Outlook for the Future. A Curriculum Unit. Fulbright-Hays Summer Seminar Abroad 1996 (South Africa). INSTITUTION Center for International Education (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 1996-00-00 NOTE 77p. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *African Studies; *Apartheid; Black Studies; Foreign Countries; Global Education; Instructional Materials; Interdisciplinary Approach; Peace; *Racial Discrimination; *Racial Segregation; Secondary Education; Social Studies; Teaching Guides IDENTIFIERS African National Congress; Mandela (Nelson); *South Africa ABSTRACT This curriculum unit is designed for students to achieve a better understanding of the South African society and the numerous changes that have recently, occurred. The four-week unit can be modified to fit existing classroom needs. The nine lessons include: (1) "A Profile of South Africa"; (2) "South African Society"; (3) "Nelson Mandela: The Rivonia Trial Speech"; (4) "African National Congress Struggle for Justice"; (5) "Laws of South Africa"; (6) "The Pass Laws: How They Impacted the Lives of Black South Africans"; (7) "Homelands: A Key Feature of Apartheid"; (8) "Research Project: The Liberation Movement"; and (9)"A Time Line." Students readings, handouts, discussion questions, maps, and bibliography are included. (EH) ******************************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. ******************************************************************************** 00 I- 4.1"Reflections on Apartheid in South Africa: Perspectives and an Outlook for the Future" A Curriculum Unit HERE SHALL watr- ALL 5 HALLENTOEQUALARTiii. 41"It AFiacAPLAYiB(D - Wad Lli -WIr_l clal4 I.4.4i-i PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE AND DISSEMINATE THIS MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED BY (4.)L.ct.0-Aou-S TO THE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC) Johnnye R. -

UCT Mourns the Passing of Advocate George Bizos

10 September 2020 UCT mourns the passing of Advocate George Bizos The University of Cape Town (UCT) mourns the passing of distinguished human rights lawyer, liberation struggle veteran and honorary doctorate recipient Advocate George Bizos. On Wednesday, 9 September 2020, Advocate Bizos passed away peacefully at the age of 92. He led a long, principled and courageous life, with an unwavering commitment to freedom and justice for all. Bizos acted as an advocate in the 1950s for Nelson Mandela and Oliver Tambo’s law firm and played a part in all the major trials of the 50-year-long struggle against apartheid. He is credited with helping craft Mandela’s impassioned plea to the court during the famous Rivonia Trial, which is said to have swayed the judge from passing the death sentence on Mandela. In 2008 UCT recognised Bizos’s contribution to South Africa and the liberation struggle with an honorary doctorate in law. This was during a time when xenophobic violence had erupted across the country. Honouring Bizos simultaneously highlighted his contribution to the liberation struggle and the rule of law and the achievements of a man who arrived in South Africa as a refugee with no formal qualification and no grasp of local languages. Born into struggle Bizos was born in 1928 in Kirani, a small coastal village in Greece, into a struggle against fascism. His birth coincided with a volatile time in Greek politics, characterised by division and fighting between democrats and fascist royalists. The Bizos family were democrats and, following a fascist coup, Bizos’s father, Antonios, was forced to resign from his position as mayor of the village. -

Bram Fischer and the Meaning of Integrity Stephen Ellman

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of North Carolina School of Law NORTH CAROLINA JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW AND COMMERCIAL REGULATION Volume 26 | Number 3 Article 5 Summer 2001 To Live Outside the Law You Must Be Honest: Bram Fischer and the Meaning of Integrity Stephen Ellman Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj Recommended Citation Stephen Ellman, To Live Outside the Law You Must Be Honest: Bram Fischer and the Meaning of Integrity, 26 N.C. J. Int'l L. & Com. Reg. 767 (2000). Available at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj/vol26/iss3/5 This Comments is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Journal of International Law and Commercial Regulation by an authorized editor of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To Live Outside the Law You Must Be Honest: Bram Fischer and the Meaning of Integrity Cover Page Footnote International Law; Commercial Law; Law This comments is available in North Carolina Journal of International Law and Commercial Regulation: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj/vol26/iss3/5 To Live Outside the Law You Must Be Honest: Bram Fischer and the Meaning of Integrity* Stephen Ellmann** Brain Fischer could "charm the birds out of the trees."' He was beloved by many, respected by his colleagues at the bar and even by political enemies.2 He was an expert on gold law and water rights, represented Sir Ernest Oppenheimer, the most prominent capitalist in the land, and was appointed a King's Counsel by the National Party government, which was simultaneously shaping the system of apartheid.' He was also a Communist, who died under sentence of life imprisonment. -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report: Volume 2

VOLUME TWO Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 6 National Overview .......................................... 1 Special Investigation The Death of President Samora Machel ................................................ 488 Chapter 2 The State outside Special Investigation South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 42 Helderberg Crash ........................................... 497 Special Investigation Chemical and Biological Warfare........ 504 Chapter 3 The State inside South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 165 Special Investigation Appendix: State Security Forces: Directory Secret State Funding................................... 518 of Organisations and Structures........................ 313 Special Investigation Exhumations....................................................... 537 Chapter 4 The Liberation Movements from 1960 to 1990 ..................................................... 325 Special Investigation Appendix: Organisational structures and The Mandela United -

KEEP the PRESSURE ON! What's Going on in South Africa? Laws, and Discrediting the All-White Sentation

Published by the New York Labor Committee Against Apartheid co CWA Local 1180, 6 Harrison St ., New York 10013 KEEP THE PRESSURE ON! What's going on in South Africa? laws, and discrediting the all-white sentation. The "stay-away" shut down This September, we watched 50,000 elections held this September. factories, schools, shops and transport. protestors march legally and peaceful- The Defiance Campaign has re-ig- ly through Cape Town, without a hint nited the democratic opposition. looking Abroad of police repression . Then newly- Through non-violent direct action, elected president F.W. DeKlerk thousands have participated in in- As the Defiance Campaign con- declares that the door is open for the tegrating hospitals, beaches, parks, tinues, the government has been reform of the apartheid system. In Oc- and workplace canteens. Workers pushed into more visible concessions. tober, eight national heroes of the anti- have held meetings and sing-ins on the It has allowed several municipalities to apartheid struggle are released from trains during their long commutes to repeal "petty apartheid" rules, like long imprisonment, including ANC work. School children and teachers segregated parks. leader Walter Sisulu. staged marches, college students set On October 4, in its most dramatic Are apartheid's rulers giving up at up barricades, and unions called a con- gesture, Pretoria released the country's last? sumer boycott. Banned organizations leading political prisoners, with the Hardly. At the same time the held public rallies to "unban" them- significant exception of Nelson Man- government was making highly selves. dela. publicized concessions, it was also kill- On September 6, three million DeKlerk's gestures are directed at ing 27 election protestors, putting joined a national strike to protest the international as well as internal hundreds more in detention, raiding elections, which exclude blacks from audiences. -

The Johnny Clegg Band Opening Act Guitar, Vocals Jesse Clegg

SRO Artists SRO The Johnny Clegg Band Opening Act Guitar, Vocals Jesse Clegg The Johnny Clegg Band Guitar, Vocals, Concertina Johnny Clegg Guitar, Musical Director Andy Innes Keyboard, Sax, Vocals Brendan Ross Percussion Barry Van Zyl Bass, Vocals Trevor Donjeany Percussion Tlale Makhene PROGRAM There will be an intermission. Sunday, April 3 @ 7 PM Zellerbach Theatre Part of the African Roots, American Voices series. 15/16 Season 45 ABOUT THE ARTISTS Johnny Clegg is one of South Africa’s most celebrated sons. He is a singer, songwriter, dancer, anthropologist and musical activist whose infectious crossover music, a vibrant blend of Western pop and African Zulu rhythms, has exploded onto the international scene and broken through all the barriers in his own country. In France, where he enjoys a massive following, he is fondly called Le Zulu Blanc – the white Zulu. Over three decades, Clegg has sold over five million albums of his brand of crossover music worldwide. He has wowed vast audiences with his audacious live shows and won a number of national and international awards for his music and his outspoken views on apartheid, perspectives on migrant workers in South Africa and the general situation in the world today. Clegg’s history is as bold, colorful and dashing as the rainbow country which he has called home for more than 40 years. Clegg was born in Bacup, near Rochdale, England, in 1953, but was brought up in Zimbabwe and South Africa. Between his mother (a cabaret and jazz singer) and his step-father (a crime reporter who took him into the townships at an early age), Clegg was exposed to a broader cultural perspective than that available to his peers.