Salamanders of Tennessee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pond-Breeding Amphibian Guild

Supplemental Volume: Species of Conservation Concern SC SWAP 2015 Pond-breeding Amphibians Guild Primary Species: Flatwoods Salamander Ambystoma cingulatum Carolina Gopher Frog Rana capito capito Broad-Striped Dwarf Siren Pseudobranchus striatus striatus Tiger Salamander Ambystoma tigrinum Secondary Species: Upland Chorus Frog Pseudacris feriarum -Coastal Plain only Northern Cricket Frog Acris crepitans -Coastal Plain only Contributors (2005): Stephen Bennett and Kurt A. Buhlmann [SCDNR] Reviewed and Edited (2012): Stephen Bennett (SCDNR), Kurt A. Buhlmann (SREL), and Jeff Camper (Francis Marion University) DESCRIPTION Taxonomy and Basic Descriptions This guild contains 4 primary species: the flatwoods salamander, Carolina gopher frog, dwarf siren, and tiger salamander; and 2 secondary species: upland chorus frog and northern cricket frog. Primary species are high priority species that are directly tied to a unifying feature or habitat. Secondary species are priority species that may occur in, or be related to, the unifying feature at some time in their life. The flatwoods salamander—in particular, the frosted flatwoods salamander— and tiger salamander are members of the family Ambystomatidae, the mole salamanders. Both species are large; the tiger salamander is the largest terrestrial salamander in the eastern United States. The Photo by SC DNR flatwoods salamander can reach lengths of 9 to 12 cm (3.5 to 4.7 in.) as an adult. This species is dark, ranging from black to dark brown with silver-white reticulated markings (Conant and Collins 1991; Martof et al. 1980). The tiger salamander can reach lengths of 18 to 20 cm (7.1 to 7.9 in.) as an adult; maximum size is approximately 30 cm (11.8 in.). -

Comparative Osteology and Evolution of the Lungless Salamanders, Family Plethodontidae David B

COMPARATIVE OSTEOLOGY AND EVOLUTION OF THE LUNGLESS SALAMANDERS, FAMILY PLETHODONTIDAE DAVID B. WAKE1 ABSTRACT: Lungless salamanders of the family Plethodontidae comprise the largest and most diverse group of tailed amphibians. An evolutionary morphological approach has been employed to elucidate evolutionary rela tionships, patterns and trends within the family. Comparative osteology has been emphasized and skeletons of all twenty-three genera and three-fourths of the one hundred eighty-three species have been studied. A detailed osteological analysis includes consideration of the evolution of each element as well as the functional unit of which it is a part. Functional and developmental aspects are stressed. A new classification is suggested, based on osteological and other char acters. The subfamily Desmognathinae includes the genera Desmognathus, Leurognathus, and Phaeognathus. Members of the subfamily Plethodontinae are placed in three tribes. The tribe Hemidactyliini includes the genera Gyri nophilus, Pseudotriton, Stereochilus, Eurycea, Typhlomolge, and Hemidac tylium. The genera Plethodon, Aneides, and Ensatina comprise the tribe Pleth odontini. The highly diversified tribe Bolitoglossini includes three super genera. The supergenera Hydromantes and Batrachoseps include the nominal genera only. The supergenus Bolitoglossa includes Bolitoglossa, Oedipina, Pseudoeurycea, Chiropterotriton, Parvimolge, Lineatriton, and Thorius. Manculus is considered to be congeneric with Eurycea, and Magnadig ita is congeneric with Bolitoglossa. Two species are assigned to Typhlomolge, which is recognized as a genus distinct from Eurycea. No. new information is available concerning Haptoglossa. Recognition of a family Desmognathidae is rejected. All genera are defined and suprageneric groupings are defined and char acterized. Range maps are presented for all genera. Relationships of all genera are discussed. -

Reproductive Biology of the Southern Dwarf Siren, Pseudobranchus Axanthus, in Southern Florida Zachary Cole Adcock University of South Florida, [email protected]

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School January 2012 Reproductive Biology of the Southern Dwarf Siren, Pseudobranchus axanthus, in Southern Florida Zachary Cole Adcock University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Biology Commons Scholar Commons Citation Adcock, Zachary Cole, "Reproductive Biology of the Southern Dwarf Siren, Pseudobranchus axanthus, in Southern Florida" (2012). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/3941 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reproductive Biology of the Southern Dwarf Siren, Pseudobranchus axanthus, in Southern Florida by Zachary C. Adcock A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Integrative Biology College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Co-Major Professor: Earl D. McCoy, Ph.D. Co-Major Professor: Henry R. Mushinsky, Ph.D. Stephen M. Deban, Ph.D. Date of Approval: July 10, 2012 Keywords: aquatic salamander, life history, oviposition, clutch size, size at maturity Copyright © 2012, Zachary C. Adcock ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I thank my co-major professors, Henry Mushinsky and Earl McCoy, for their patience and guidance through a couple of thesis projects lasting several years. I also thank my committee member, Steve Deban, for providing excellent comments to improve this thesis document. -

Aquatic Feeding in Salamanders

CHAPTER 3 Aquatic Feeding in Salamanders STEPHEN M. DEBAN AND DAVID B. WAKE Museum of Vertebrate Zoology and Department oflntegrative Biology University of California Berkeley, California 94720 I. INTRODUCTION canum. Some undergo partial metamorphosis and pos- A. Systematics sess both adult and larval features when reproductive, B. Natural History such as the fully aquatic Cryptobranchus. Others are C. Feeding Modes and Terminology primarily terrestrial and become secondarily aquatic 11. MORPHOLOGY as metamorphosed adults, notably during the breed- A. Larval Morphology ing season. The family Salamandridae contains the B. Adult Morphology most representatives of this type, known commonly C. Sensory and Motor Systems as newts. 111. FUNCTION A. Ingestion Behavior and Kinematics Salamanders covered in this chapter may be terres- B. Prey Processing trial, semiaquatic, or fully aquatic. They may return to C. Functional Morphology the water only periodically and may feed on both land D. Biomechanics and in water. Discussion here focuses on the aquatic E. Metamorphosis feeding biology of these taxa. Terrestrial feeding of F. Performance semiaquatic and terrestrial salamanders is discussed G. Variation in the next chapter. Here we describe the various feed- IV. DIVERSITY AND EVOLUTION ing behaviors: foraging, ingestion (prey capture), prey A. Features of Salamander Families processing, intraoral prey transport, and swallowing. B. Phylogenetic Patterns of Feeding Form and Function We review the relevant morphology and function of V. OPPORTUNITIES FOR FUTURE RESEARCH the sensory and motor systems and analyze the bio- References mechanical function of the feeding apparatus. Finally, we consider the evolution of aquatic feeding systems within and among the major taxa of salamanders. -

TRAPPING SUCCESS and POPULATION ANALYSIS of Siren Lacertina and Amphiuma Means

TRAPPING SUCCESS AND POPULATION ANALYSIS OF Siren lacertina AND Amphiuma means By KRISTINA SORENSEN A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2003 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I thank my committee members Lora Smith, Franklin Percival, and Dick Franz for all their support and advice. The Department of Interior's Student Career Experience Program and the U.S. Geological Survey's Amphibian Research and Monitoring Initiative provided funding for this project. I thank those involved with these programs who have helped me over the last three years: David Trauger, Ken Dodd, Jamie Barichivich, Jennifer Staiger, Kevin Smith, and Steve Johnson. Numerous people helped with field work: Audrey Owens, Maya Zacharow, Chris Gregory, Matt Chopp, Amanda Rice, Paul Loud, Travis Tuten, Steve Johnson, and Jennifer Staiger, Lora Smith, and the UF Wildlife Field Techniques Courses of2001-2002. Paul Moler and John Jensen provided advice and shared their wealth of herpetological knowledge. I thank the staff of Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge and Steve Coates, manager of the Ordway Preserve, for their assistance on numerous occasions and for permission to conduct research on their property. Marinela Capanu of the IFAS Statistical Consulting Unit assisted with statistical analysis. Julien Martin, Bob Dorazio, Rob Bennets, and Cathy Langtimm provided advice on population analysis. I also thank the administrative staff of the Florida Caribbean Science Center and the Florida Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit. I am much indebted to all of these people, without whom this thesis would not have been possible. -

The Salamanders of Tennessee

Salamanders of Tennessee: modified from Lisa Powers tnwildlife.org Follow links to Nongame The Salamanders of Tennessee Photo by John White Salamanders are the group of tailed, vertebrate animals that along with frogs and caecilians make up the class Amphibia. Salamanders are ectothermic (cold-blooded), have smooth glandular skin, lack claws and must have a moist environment in which to live. 1 Amphibian Declines Worldwide, over 200 amphibian species have experienced recent population declines. Scientists have reports of 32 species First discovered in 1967, the golden extinctions, toad, Bufo periglenes, was last seen mainly species of in 1987. frogs. Much attention has been given to the Anurans (frogs) in recent years, however salamander populations have been poorly monitored. Photo by Henk Wallays Fire Salamander - Salamandra salamandra terrestris 2 Why The Concern For Salamanders in Tennessee? Their key role and high densities in many forests The stability in their counts and populations Their vulnerability to air and water pollution Their sensitivity as a measure of change The threatened and endangered status of several species Their inherent beauty and appeal as a creature to study and conserve. *Possible Factors Influencing Declines Around the World Climate Change Habitat Modification Habitat Fragmentation Introduced Species UV-B Radiation Chemical Contaminants Disease Trade in Amphibians as Pets *Often declines are caused by a combination of factors and do not have a single cause. Major Causes for Declines in Tennessee Habitat Modification -The destruction of natural habitats is undoubtedly the biggest threat facing amphibians in Tennessee. Housing, shopping center, industrial and highway construction are all increasing throughout the state and consequently decreasing the amount of available habitat for amphibians. -

Amphibian and Reptile Checklist

KEY TO ABBREVIATIONS ___ Eastern Rat Snake (Pantherophis alleghaniensis) – BLUE RIDGE (NC‐C, VA‐C) Habitat: Varies from rocky timbered hillsides to flat farmland. The following codes refer to an animal’s abundance in ___ Eastern Hog‐nosed Snake (Heterodon platirhinos) – PARKWAY suitable habitat along the parkway, not the likelihood of (NC‐R, VA‐U) Habitat: Sandy or friable loam soil seeing it. Information on the abundance of each species habitats at lower elevation. AMPHIBIAN & comes from wildlife sightings reported by park staff and ___ Eastern Kingsnake (Lampropeltis getula) – (NC‐U, visitors, from other agencies, and from park research VA‐U) Habitat: Generalist at low elevations. reports. ___ Northern Mole Snake (Lampropeltis calligaster REPTILE C – COMMON rhombomaculata) – (VA‐R) Habitat: Mixed pine U – UNCOMMON forests and open fields under logs or boards. CHECKLIST R – RARE ___ Eastern Milk Snake (Lampropeltis triangulum) – (NC‐ U, VA‐U) Habitat: Woodlands, grassy balds, and * – LISTED – Any species federally or state listed as meadows. Endangered, Threatened, or of Special Concern. ___ Northern Water Snake (Nerodia sipedon sipedon) – (NC‐C, VA‐C) Habitat: Wetlands, streams, and lakes. Non‐native – species not historically present on the ___ Rough Green Snake (Opheodrys aestivus) – (NC‐R, parkway that have been introduced (usually by humans.) VA‐R) Habitat: Low elevation forests. ___ Smooth Green Snake (Opheodrys vernalis) – (VA‐R) NC – NORTH CAROLINA Habitat: Moist, open woodlands or herbaceous Blue Ridge Red Cope's Gray wetlands under fallen debris. Salamander Treefrog VA – VIRGINIA ___ Northern Pine Snake (Pituophis melanoleucus melanoleucus) – (VA‐R) Habitat: Abandoned fields If you see anything unusual while on the parkway, please and dry mountain ridges with sandier soils. -

Streamside Salamander Identification Guide

Key to the Identification of Streamside Salamanders 1 Ambystoma spp., mole salamanders (Family Ambystomatidae) Appearance: Medium to large stocky salamanders. Large round heads with bulging eyes. Larvae are also stocky and have elaborate gills. Size: 3-8” (Total length). Spotted salamander, Ambystoma maculatum Habitat: Burrowers that spend much of their life below ground in terrestrial habitats. Some species, (e.g. marbled salamander) may be found under logs or other debris in riparian areas. All species breed in fishless isolated ponds or wetlands. Range: Statewide. Other: Five species in Georgia. This group includes some of the largest and most dramatically patterned terrestrial species. Marbled salamander, Ambystoma opacum Amphiuma spp., amphiuma (Family Amphiumidae) Appearance: Gray to black, eel-like bodies with four greatly reduced, non-functional legs (A). Size: up to 46” (Total length) Habitat: Lakes, ponds, ditches and canals, one species is found in deep pockets of mud along the Apalachicola River floodplains. A Range: Southern half of the state. A Other: One species, the two-toed amphiuma (A. means), shown on the right, is known to occur in A. pholeter southern Georgia; a second species, ,Two-toed amphiuma, Amphiuma means may occur in extreme southwest Georgia, but has yet to be confirmed. The two-toed amphiuma (shown in photo) has two diminutive toes on each of the front limbs. 2 Cryptobranchus alleganiensis, hellbender (Family Cryptobranchidae) Appearance: Very large, wrinkled salamander with eyes positioned laterally (A). Brown-gray in color with darker splotches Size: 12-29” (Total length) A Habitat: Large, rocky, fast-flowing streams. Often found beneath large rocks in shallow rapids. -

Standard Common and Current Scientific Names for North American Amphibians, Turtles, Reptiles & Crocodilians

STANDARD COMMON AND CURRENT SCIENTIFIC NAMES FOR NORTH AMERICAN AMPHIBIANS, TURTLES, REPTILES & CROCODILIANS Sixth Edition Joseph T. Collins TraVis W. TAGGart The Center for North American Herpetology THE CEN T ER FOR NOR T H AMERI ca N HERPE T OLOGY www.cnah.org Joseph T. Collins, Director The Center for North American Herpetology 1502 Medinah Circle Lawrence, Kansas 66047 (785) 393-4757 Single copies of this publication are available gratis from The Center for North American Herpetology, 1502 Medinah Circle, Lawrence, Kansas 66047 USA; within the United States and Canada, please send a self-addressed 7x10-inch manila envelope with sufficient U.S. first class postage affixed for four ounces. Individuals outside the United States and Canada should contact CNAH via email before requesting a copy. A list of previous editions of this title is printed on the inside back cover. THE CEN T ER FOR NOR T H AMERI ca N HERPE T OLOGY BO A RD OF DIRE ct ORS Joseph T. Collins Suzanne L. Collins Kansas Biological Survey The Center for The University of Kansas North American Herpetology 2021 Constant Avenue 1502 Medinah Circle Lawrence, Kansas 66047 Lawrence, Kansas 66047 Kelly J. Irwin James L. Knight Arkansas Game & Fish South Carolina Commission State Museum 915 East Sevier Street P. O. Box 100107 Benton, Arkansas 72015 Columbia, South Carolina 29202 Walter E. Meshaka, Jr. Robert Powell Section of Zoology Department of Biology State Museum of Pennsylvania Avila University 300 North Street 11901 Wornall Road Harrisburg, Pennsylvania 17120 Kansas City, Missouri 64145 Travis W. Taggart Sternberg Museum of Natural History Fort Hays State University 3000 Sternberg Drive Hays, Kansas 67601 Front cover images of an Eastern Collared Lizard (Crotaphytus collaris) and Cajun Chorus Frog (Pseudacris fouquettei) by Suzanne L. -

Terrestrial Ecosystems 3 Chapter 1

TERRESTRIAL Chapter 1: Terrestrial Ecosystems 3 Chapter 1: What are the history, Terrestrial status, and projected future of terrestrial wildlife habitat types and Ecosystems species in the South? Margaret Katherine Trani (Griep) Southern Region, USDA Forest Service ■ Since presettlement, there have insect infestation, advanced age, Key Findings been significant losses of community climatic processes, and distur- biodiversity in the South (Noss and bance influence mast yields. ■ There are 132 terrestrial vertebrate others 1995). Fourteen communities ■ The ranges of many species species that are considered to be are critically endangered (greater cross both public and private of conservation concern in the South than 98-percent decline), 25 are land ownerships. The numbers of by State Natural Heritage agencies. endangered (85- to 98-percent imperiled and endangered species Of the species that warrant conser- decline), and 11 are threatened inhabiting private land indicate its vation focus, 3 percent are classed (70- to 84-percent decline). Common critical importance for conservation. factors contributing to the loss of as critically imperiled, 3 percent ■ The significance of land owner- as imperiled, and 6 percent as these communities include urban development, fire suppression, ship in the South for the provision vulnerable. Eighty-six percent of species habitat cannot be of terrestrial vertebrate species exotic species invasion, and recreational activity. overstated. Each major landowner are designated as relatively secure. has an important role to play in ■ The remaining 2 percent are either The term “fragmentation” the conservation of species and known or presumed to be extinct, references the insularization of their habitats. or have questionable status. habitat on a landscape. -

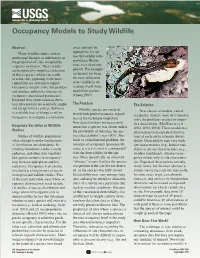

Occupancy Models to Study Wildlife June When Salamanders Were Believed 2

unit. Sample units were near trails and Further Reading Caudata) populations: a twenty-year and dynamics of species occurance. located approximately 250 m apart study in the southern Appalachians. Academic Press. Glossary: Ash, A. N. 1997. Disappearance and to ensure independence among sites. Brimleyana 18: 59-64. return of salamanders to clearcut plots Thirty-nine sites were sampled once 1. State variable: variable used to characterize the status of the wild- O’Connell, A. F., N. W. Talancy, L. in the southern Blue Ridge Mountains. Hanski, I. 1992. Inferences from eco- L. Bailey, J. R. Sauer, R. Cook and every two weeks from April to mid- life system of interest; the system being studied. Conservation Biology 11: 983-989. logical incidence functions. American A. T. Gilbert. 2005. Estimating site Occupancy Models to Study Wildlife June when salamanders were believed 2. Occupancy: the proportion of sites, patches, or habitat units oc- Naturalist 139: 657-662. occupancy and detection probability to be most active and near the surface. Ash, A. N. and K. H. Pollock. 1999. cupied by a species. parameters for mammals in a coastal However, we detected no salaman- Clearcuts, salamanders and field stud- 3. Detectability: the probability of detecting a species during a single Kendall, W. L. 1999. Robustness of ecosystem. Journal of Wildlife Man- ders of the Desmognathus imitator ies. Conservation Biology 13: 206- Abstract areas and may be survey, given it is present at the site. closed capture–recapture methods to agement 69: in press. 208. violations of the closure assumption. appropriate for spe- Coverboards Many wildlife studies seek to 4. -

Legal Authority Over the Use of Native Amphibians and Reptiles in the United States State of the Union

STATE OF THE UNION: Legal Authority Over the Use of Native Amphibians and Reptiles in the United States STATE OF THE UNION: Legal Authority Over the Use of Native Amphibians and Reptiles in the United States Coordinating Editors Priya Nanjappa1 and Paulette M. Conrad2 Editorial Assistants Randi Logsdon3, Cara Allen3, Brian Todd4, and Betsy Bolster3 1Association of Fish & Wildlife Agencies Washington, DC 2Nevada Department of Wildlife Las Vegas, NV 3California Department of Fish and Game Sacramento, CA 4University of California-Davis Davis, CA ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS WE THANK THE FOLLOWING PARTNERS FOR FUNDING AND IN-KIND CONTRIBUTIONS RELATED TO THE DEVELOPMENT, EDITING, AND PRODUCTION OF THIS DOCUMENT: US Fish & Wildlife Service Competitive State Wildlife Grant Program funding for “Amphibian & Reptile Conservation Need” proposal, with its five primary partner states: l Missouri Department of Conservation l Nevada Department of Wildlife l California Department of Fish and Game l Georgia Department of Natural Resources l Michigan Department of Natural Resources Association of Fish & Wildlife Agencies Missouri Conservation Heritage Foundation Arizona Game and Fish Department US Fish & Wildlife Service, International Affairs, International Wildlife Trade Program DJ Case & Associates Special thanks to Victor Young for his skill and assistance in graphic design for this document. 2009 Amphibian & Reptile Regulatory Summit Planning Team: Polly Conrad (Nevada Department of Wildlife), Gene Elms (Arizona Game and Fish Department), Mike Harris (Georgia Department of Natural Resources), Captain Linda Harrison (Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission), Priya Nanjappa (Association of Fish & Wildlife Agencies), Matt Wagner (Texas Parks and Wildlife Department), and Captain John West (since retired, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission) Nanjappa, P.