John Nesbitt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Politics of Roman Memory in the Age of Justinian DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the D

The Politics of Roman Memory in the Age of Justinian DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Marion Woodrow Kruse, III Graduate Program in Greek and Latin The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Anthony Kaldellis, Advisor; Benjamin Acosta-Hughes; Nathan Rosenstein Copyright by Marion Woodrow Kruse, III 2015 ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the use of Roman historical memory from the late fifth century through the middle of the sixth century AD. The collapse of Roman government in the western Roman empire in the late fifth century inspired a crisis of identity and political messaging in the eastern Roman empire of the same period. I argue that the Romans of the eastern empire, in particular those who lived in Constantinople and worked in or around the imperial administration, responded to the challenge posed by the loss of Rome by rewriting the history of the Roman empire. The new historical narratives that arose during this period were initially concerned with Roman identity and fixated on urban space (in particular the cities of Rome and Constantinople) and Roman mythistory. By the sixth century, however, the debate over Roman history had begun to infuse all levels of Roman political discourse and became a major component of the emperor Justinian’s imperial messaging and propaganda, especially in his Novels. The imperial history proposed by the Novels was aggressivley challenged by other writers of the period, creating a clear historical and political conflict over the role and import of Roman history as a model or justification for Roman politics in the sixth century. -

9781107404748 Index.Pdf

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-40474-8 - John Skylitzes: A Synopsis of Byzantine History, 811–1057 John Wortley Index More information Index Aaron, brother-in-law of Isaac I Komnenos , A n a t o l i a , Aaron, son of John Vladisthlav , A n a t o l i k o n , , , , , , , , , , , , A b e l b a k e s , , , , , , , , , , , A b o u l c h a r e , , , , , , , A b o u z a c h a r , Andrew the Scyth , A b r a m , , , Andrew the stratelates , , A b r a m i t e s , m o n a s t e r y o f t h e , A n d r o n i k o s D o u k a s , , A b u H a f s , , , , A n e m a s , , , A b y d o s , , , , , , , , , , A n i , , , , , , , , , , , A n n a , s i s t e r o f B a s i l I I , x i , x x x i , , , , , A d r i a n , , , , , , , , , , , A d r i a n o p l e , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , A n t h e m i o s , m o n a s t e r y a t , , , , Anthony Kauleas, patriarch , , A e t i o s , Anthony the Stoudite, patriarch , A f r i c a , , , , , , , , , , A n t i g o n u s , d o m e s t i c o f t h e s c h o l a i , , , , , A n t i g o n o s , s o n o f B a r d a s , , A g r o s , m o n a s t e r y , A n z e s , , A i k a t e r i n a d a u g h t e r o f V l a d i s t h l a v , Aplesphares, ruler of Tivion -

Black Sea-Caspian Steppe: Natural Conditions 20 1.1 the Great Steppe

The Pechenegs: Nomads in the Political and Cultural Landscape of Medieval Europe East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450–1450 General Editors Florin Curta and Dušan Zupka volume 74 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/ecee The Pechenegs: Nomads in the Political and Cultural Landscape of Medieval Europe By Aleksander Paroń Translated by Thomas Anessi LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Publication of the presented monograph has been subsidized by the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education within the National Programme for the Development of Humanities, Modul Universalia 2.1. Research grant no. 0046/NPRH/H21/84/2017. National Programme for the Development of Humanities Cover illustration: Pechenegs slaughter prince Sviatoslav Igorevich and his “Scythians”. The Madrid manuscript of the Synopsis of Histories by John Skylitzes. Miniature 445, 175r, top. From Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. Proofreading by Philip E. Steele The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available online at http://catalog.loc.gov LC record available at http://catalog.loc.gov/2021015848 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. -

Constantinople 1 L Shaped H

The Shroud of Turin in Constantinople? Paper I An analysis of the L Shaped markings on the Shroud of Turin and an examination of the Holy Mandylion and Holy Shroud in the Madrid Skylitzes © Pam Moon Introduction This paper begins by looking at the pattern of marks on the Shroud of Turin which look like an L shape. The paper examines [1] the folding patterns, [2] the probable cause of the burn marks, and argues, with Aldo Guerreschi and Michele Salcito that it is accidental damage from incense. [3] It compares the marks with the Hungarian Pray manuscript. [4] In the second part, the paper looks at the historical text The Synopsis of the Histories attributed to Ioannes (John) Skylitzes. The illustrated history is known as the Madrid Skylitzes. It is the only surviving illustrated manuscript for Byzantine history for the ninth, tenth and eleventh centuries. The paper looks at images from the Madrid Skylitzes which relate to the Holy Mandylion, also known as the Image of Edessa. The Mandylion was the most precious artefact in the Byzantine empire and is repeatedly described as an image ‘not-made-by-hands.’ [5] The paper identifies a miniature in the Madrid Skylitzes (fol.26v; see below) which apparently shows the procession of a beheaded emperor Leon V in AD 820 and suggests that there could be a scribal error. The picture seems to show the Varangian Guard who arrived in Constantinople after AD 988, 168 years later. The picture may instead depict the procession of AD 1036, where the Holy Mandylion (and in some translations Holy Shroud) were carried though the streets of Constantinople. -

Robert Graves the White Goddess

ROBERT GRAVES THE WHITE GODDESS IN DEDICATION All saints revile her, and all sober men Ruled by the God Apollo's golden mean— In scorn of which I sailed to find her In distant regions likeliest to hold her Whom I desired above all things to know, Sister of the mirage and echo. It was a virtue not to stay, To go my headstrong and heroic way Seeking her out at the volcano's head, Among pack ice, or where the track had faded Beyond the cavern of the seven sleepers: Whose broad high brow was white as any leper's, Whose eyes were blue, with rowan-berry lips, With hair curled honey-coloured to white hips. Green sap of Spring in the young wood a-stir Will celebrate the Mountain Mother, And every song-bird shout awhile for her; But I am gifted, even in November Rawest of seasons, with so huge a sense Of her nakedly worn magnificence I forget cruelty and past betrayal, Careless of where the next bright bolt may fall. FOREWORD am grateful to Philip and Sally Graves, Christopher Hawkes, John Knittel, Valentin Iremonger, Max Mallowan, E. M. Parr, Joshua IPodro, Lynette Roberts, Martin Seymour-Smith, John Heath-Stubbs and numerous correspondents, who have supplied me with source- material for this book: and to Kenneth Gay who has helped me to arrange it. Yet since the first edition appeared in 1946, no expert in ancient Irish or Welsh has offered me the least help in refining my argument, or pointed out any of the errors which are bound to have crept into the text, or even acknowledged my letters. -

Byzantine Critiques of Monasticism in the Twelfth Century

A “Truly Unmonastic Way of Life”: Byzantine Critiques of Monasticism in the Twelfth Century DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Hannah Elizabeth Ewing Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Professor Timothy Gregory, Advisor Professor Anthony Kaldellis Professor Alison I. Beach Copyright by Hannah Elizabeth Ewing 2014 Abstract This dissertation examines twelfth-century Byzantine writings on monasticism and holy men to illuminate monastic critiques during this period. Drawing upon close readings of texts from a range of twelfth-century voices, it processes both highly biased literary evidence and the limited documentary evidence from the period. In contextualizing the complaints about monks and reforms suggested for monasticism, as found in the writings of the intellectual and administrative elites of the empire, both secular and ecclesiastical, this study shows how monasticism did not fit so well in the world of twelfth-century Byzantium as it did with that of the preceding centuries. This was largely on account of developments in the role and operation of the church and the rise of alternative cultural models that were more critical of traditional ascetic sanctity. This project demonstrates the extent to which twelfth-century Byzantine society and culture had changed since the monastic heyday of the tenth century and contributes toward a deeper understanding of Byzantine monasticism in an under-researched period of the institution. ii Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my family, and most especially to my parents. iii Acknowledgments This dissertation is indebted to the assistance, advice, and support given by Anthony Kaldellis, Tim Gregory, and Alison Beach. -

The Birth of Territory

the birth of territory The Birth of Territory stuart elden the university of chicago press chicago and london Stuart Elden is professor of political theory and geography at the University of Warwick. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2013 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 2013. Printed in the United States of America 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 1 2 3 4 5 isbn-13: 978-0-226-20256-3 (cloth) isbn-13: 978-0-226-20257-0 (paper) isbn-13: 978-0-226-04128-5 (e-book) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Elden, Stuart, 1971- The birth of territory / Stuart Elden. pages. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-0-226-20256-3 (cloth : alk. paper)—isbn 978-0-226-20257-0 (pbk. : alk. paper)—isbn 978-0-226-04128-5 (e-book) 1. Political geography. 2. Geography, Ancient. 3. Geography, Medieval. I. Title. jc319.e44 2013 320.1’2—dc23 2013005902 This paper meets the requirements of ansi/niso z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction 1 Part I 19 1. The Polis and the Khora 21 Autochthony and the Myth of Origins 21 Antigone and the Polis 26 The Reforms of Kleisthenes 31 Plato’s Laws 37 Aristotle’s Politics 42 Site and Community 47 2. From Urbis to Imperium 53 Caesar and the Terrain of War 55 Cicero and the Res Publica 60 The Historians: Sallust, Livy, Tacitus 67 Augustus and Imperium 75 The Limes of the Imperium 82 Part II 97 3. -

The Byzantine Empire.Pdf

1907 4. 29 & 30 BEDFORD STREET, LONDON . BIBLIOTECA AIEZAMANTULUI CULTURAL 66)/ NICOLAE BALCESCU" TEMPLE PRIMERS THE BYZANTINE EMPIRE bY N. JORGA Translated from the French by ALLEN H. POWLES, M.A. All rights reserved AUTHOR'S PREFACE THIs new history of Byzantium, notwithstanding its slender proportions, has been compiled from the original sources. Second-hand materials have only been used to compare the results obtained by the author with those which his pre- decessors have reached. The aim in. view has not been to present one more systematic chronology of Byzantine history, considered as a succession of tragic anecdotes standing out against a permanent background.I have followed the development of Byzantine life in all its length and breadth and wealth, and I have tried to give a series of pictures rather than the customary dry narrative. It may be found possibly that I have given insufficient information on the Slav and Italian neighbours and subjects of the empire.I have thought it my duty to adopt the point of view of the Byzantines themselves and to assign to each nation the place it occupied in the minds of the politicians and thoughtful men of Byzantium.This has been done in such a way as not to prejudicate the explanation of the Byzantine transformations. Much less use than usual has been made of the Oriental sources.These are for the most part late, and inaccuracy is the least of their defects.It is clear that our way of looking v vi AUTHOR'S PREFACE at and appreciatingeventsismuch morethat of the Byzantines than of the Arabs.In the case of these latter it is always necessary to adopt a liberal interpretation, to allow for a rhetoric foreign to our notions, and to correct not merely the explanation, but also the feelings which initiated it.We perpetually come across a superficial civilisation and a completely different race. -

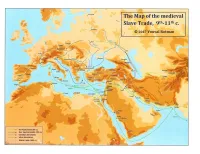

The Map Is Based on the Following Data Organized Chronologically and Geographically

The map is based on the following data organized chronologically and geographically Table 1: data concerning the slave trade in the medieval Mediterranean 8th-11th c. Western Europe Central Europe Italy-Adriatic Sea Syria-Palestine- Byzantium Balkans Caucasus-Black Iraq-Iran Egypt Sea-Russia 7th –8th c.: the 712: first Rhodian Sea Law kommerkiarioi, 729: Itil, first (mentions of attested in evidences 776: letter from trafficked slaves) Thessalonica 740: documents 762: Abbassids Pope Hadrian I to 728: last known (including of slaves) attesting Jews settle in Charlemagne sigillographical among the Baghdad regarding the mention of Khazars slave trade apothēkai 801: Irene lowers 8th c.: Abydikoi taxes (responsible of 812/814: the 809: Nicephorus I import taxes) of Franks leave the taxes slaves Thessalonica Adriatic Sea entering by the attested 822–852: al- 814–820: 824: Arab Dodecanese Ghazāl on the Byzantino- conquest of Crete Spain-Baltic Venetian edict routes against trade 833–844: Arab 841: the thema of 846: first 825: privileges with the Arabs raids in Sicily and 831–833: new Kherson version of granted by Louis 831: Arab Peloponnesus; kommerkiarioi mid-ninth Kitāb al- the Pious to a conquest of Byzantine raids century: Masālik wa’l- Jewish merchant Palermo in Syria 860: the Serbs pay -Life of George of mamālik, by of Sargossa 830–860: Arab their tribute to the Amastris (tax in Ibn 846: Agobard of raids in southern Bulgars in slaves Trebizond). Ḵhurradāḏhbih Lyons writes Italy 864: - Rus’ merchants : references to against the Christianization -

Alexius Komnenos and the West and So It Begins...76Th Emperor

3/14/2012 Alexius Komnenos and the West HIST 302 Spring 2012 And so it begins...76th Emperor 4 April 1081 ascended to the throne • 24 years old • short and stocky; deep chested; broad shoulders • seen action against the Seljuks – never lost a battle • uncle was Isaac Komnenus • married to the 15 year old Irene Ducas – assured support of aristocracy and clergy • his ascension was a little messy... Komneni Dynasty (1081-1185) 1057-9 Isaac I 1071 Battle of Manzikert 1081-1118 Alexios I 1118-43 John II 1143-80 Manuel I 1180-2 Alexios II 1182-5 Andronikos I 1 3/14/2012 War with the Normans • Robert Guiscard (the crafty) 1071 Bari fell 1081 giant fleet sailed towards Durazzo – road to Constantinople • Alexius shows up with his army – Varangians (mostly A-S refugees pissed off at Normans) wanting revenge • Alexius wounded in battle – retires to Thessalonica 2 3/14/2012 Gregory VII, besieged in Castel Sant'Angelo Tomb of Guiscard at Venosa Robert Guiscard dies of Typhoid in 1085 Normans Conquer S. Italy • Normans conquer Sicily and S. Italy • Cousin of Roger Guiscard organizes a new Kingdom Roger II, the Norman (ruled from 1130-1154) 3 3/14/2012 Palazzo Reale, Naples Roger II Frederick II Alfonso Charles V Charles III Charles of Anjou Gioacchino Murat Victor Emanuel II Norman Hohenstaufen Aragon Hapsburg Bourbon (1266-1285) (1808-1815) (1861-1878) (1130-1154) (1211-1250) (1442-1458) (1520-1558) (1734-1759) Alexius Receives Papal Mission Pope Gregory VII – excommunicated Alexius for helping HRE Pope Urban II • trying to restore unity b/t E &W -

Three Byzantine Lead Seals from Devolgrad (Ancient Audaristos) Near Stobi

Robert Mihaj lovski Three Byzantine Lead Seals from Devolgrad (Ancient Audaristos) near Stobi Three Byzantine lead seals were found in the grazing lands and vineyards at Devolgrad, thirteen kilometres west of Stobi, in the district of Kavadarci (Republic of Macedonia). [Fig. 101] In 2001 they became part of a private collection. 1 They are not unique nor are they important in themselves. But they do have significance in that they are among a relatively small group of seals which can be related toa particular place. Devolgrad, also known as Diabolis, was a fortress which had been occupied successively in prehistorie, Paeonian, Macedonian, Roman and Byzantine times. Located on the massive limestone rock at the entrance of the gorge of the river Raec near the village of Drenovo, it controlled the road communication between Stobi and Heraclea Lyncestis on the junction of the Via Egnatia [Fig. 102], as welt as being on an ancient route connecting the Pelagonia valley with the corridor of the Vardar-Morava-Danube river system. During Roman times it was an important strategie and military post and was perhaps a fortress-refugium for the population of Stobi and its environs, as retlected in another of its names, Stypeion. Later it played an important role in the military campaigns of Emperor Basil Il in 10142 and throughout the Komnenian and Palaiologan periods. Between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries the area became an object of incessant strife between the lords of Nicaea, Epirus and Thessalonica, including the Crusader, Bulgarian and Serbian invasions. lt is thus not surprising that the first lead seal is connected with the name of the sebastos George Palaiologos, a notable military commander and a great supporter (and brother-in-law) of the Emperor Alexios I Komnenos. -

The Political Opposition to Alexios I Komnenos (1081–1118)

The Political Opposition to Alexios I Komnenos (1081–1118) Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung des Akademischen Grades eines Dr. phil., vorgelegt dem Fachbereich 07 Geschichts- und Kulturwissenschaften der Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz von João Vicente de Medeiros Publio Dias aus São Paulo, Brasilien 2020 Dekan: 1. Gutachter: 2. Gutachter: Tag des Prüfungskolloquiums: 18. Juli 2018 Dedicado a Dai Table of Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................... 1 Note on translation and transliteration .................................................................................. 2 i. Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 3 i.i. Bibliographic Review ...................................................................................................... 4 i.ii Conceptual and Theoretical Issues on Political Opposition in Byzantium ...................... 7 i.iii Sources .......................................................................................................................... 18 i.iii.i Material for History of Nikephoros Bryennios .......................................................... 24 i.iii.ii The Alexiad of Anna Komnene ................................................................................. 26 i.iii.iii The Epitome Historion of Ioannes Zonaras .............................................................. 30 i.iii.iv The Chronike