Machine of the Year the Computer Moves in by the Millions, It Is Beeping Its Way Into Offices, Schools and Homes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

200 Modi Per Recuperare Un Hard Disk

Retrocomputer Magazine Anno 2 - Numero 9 - Maggio/Giugno 2007 In prova: Jurassic Olivetti Linea 1 News Esclusiva: I migliori PC di tutti i tempi Inoltre: Virtual Texas Instruments disk Laboratorio: 200 modi per recuperare un hard Jurassic News - Anno 2 - numero 9 - maggio/giugno 2007 Jurassic News Sommario - Maggio/Giugno 2007 Rivista aperiodica di Retro Computing Editoriale Apple Club Coordinatore editoriale Novità in vista, 3 Tutti i linguaggi di Apple Tullio Nicolussi [Tn] (parte 1), 62 Redazione Retrocomputing Sonicher [Sn] Esseri liberi, 4 Retro Linguaggi I migliori PC di tutti i tempi, 6 COBOL (parte 4), 74 Hanno collaborato a questo numero: Salvatore Macomer [Sm] Come eravamo Videoteca Lorenzo 2 [L2] Maggio 1982, 14 2010 l’anno del contatto, 72 Besdelsec [Bs] Giugno 1982, 15 Edicola Impaginazione e grafica Le prove di JN Anna [An] Pluto Journal, 66 Olivetti L1, 16 Nuova Elettronica Z80, 38 Diffusione Retro Software [email protected] Visicalc, 68 Il racconto La rivista viene diffusa in Una giornata di Ivan Ivanovich, formato PDF via Inter- Biblioteca 24 net. Il costo di un singolo Linux Bible, 80 numero è di Euro 2. 101 Reasons: To Switch to the Abbonamento annuale (6 Retro Riviste MAC, 82 numeri) Euro 6. Olivetti Research & Tecnology Arretrati Euro 2 a numero. Review , 36 L’intervista Contatti Conversazione con Gianfranco, [email protected] Laboratorio 84 200 modi per resuscitare un HD Copyright L’opinione I marchi citati sono di (parte 1), 50 Della Pirateria, 88 copyrights dei rispettivi proprietari. Emulazione La riproduzione con qual- Virtual TI 2.5, 48 BBS siasi mezzo di illustrazioni Scumm e ScummVM, 56 Posta e comunicazioni, 94 e di articoli pubblicati sulla rivista, nonché la loro tra- duzione, è riservata e non può avvenire senza espres- sa autorizzazione. -

Retro Magazine World 0

Més que un Magazine TABLE OF CONTENTS ◊ The Karnak MFP810 Calculator Pag. 3 "Més que un club" (more than a club) is the slogan proudly ◊ SEGA SATURN - a fantastic but Pag. 4 displayed by Barcelona FC in the stands of its football stadium. misunderstood platform! With equal pride we can say that RetroMagazine World is more ◊ Commodore 264 Series Pag. 6 than just a magazine reserved for a group of enthusiasts. ◊ OLIVETTI, when Italy was Silicon Valley Pag. 10 ◊ Olivetti PC128S Pag. 15 With all our initiatives (the site, "Press Play Again", etc.) and the ◊ RetroLiPS project presence on the most frequented social networks, it proves to be Pag. 19 a community full of life. ◊ Nobility of a humble flowchart Pag. 20 ◊ Introduction to Commodore C128 Pag. 26 The Editorial Board has recently seen an increase in the number graphics - part 2 of collaborators, starting with Mike "The biker" Novarina, ◊ Turbo Rascal SE - A complete cross- Pag. 30 Alessandro Albano and continuing with Francesco Coppola, platform framework for 8/16-bit Beppe Rinella, Christian Miglio (humbly apologizing if we have development forgotten someone else worthy of being remembered). ◊ ATARI - The origin of the myth Pag. 34 In particular, the young Francesco Coppola will take care of the ◊ Another World: a scary and magnificent Pag. 36 journey Atari world, while Beppe Rinella will enrich the articles of games by leaving the patterns of the usual review. ◊ Road Hunter - TI99/4A Pag. 40 ◊ Wizard of Wor - Commodore 64 Pag. 42 RetroMagazine World is appreciated because it is made by ◊ F-1 Spirit: the way to Formula-1 (MSX) Pag. -

Olivetti M20 News

Retrocomputer Magazine Anno 2 - Numero 10 - Luglio/Agosto 2007 Emulazione: HP 41C Prova hardware: JurassicOlivetti M20 News 100 modi Apple Club per recuperare un hard disk (parte 2) La Rivincita di un piccolo MAc SE Jurassic News - Anno 2 - numero 10 - luglio/agosto 2007 Jurassic News Sommario - Luglio/Agosto 2007 Rivista aperiodica di Retro-computing Editoriale Coordinatore editoriale L’abbondanza e la carestia, 3 Tullio Nicolussi [Tn] Redazione Sonicher [Sn] Retrocomputing [email protected] Retro Linguaggi L’archivista, 4 COBOL (parte 5), 44 Hanno collaborato a questo numero: Come eravamo Emulazione Salvatore Macomer [Sm] Luglio/Agosto 1992, 12 HP41E, 50 Lorenzo 2 [L2] Besdelsec [Bs] Maurizio Martone [mm] Le prove di JN Retro Code Olivetti M20, 14 Bioritmi, 52 Impaginazione e grafica Anna Il racconto Apple Club Il Mega Direttore Galattico, 24 Tutti i linguaggi di Apple Diffusione [email protected] (parte 2), 56 La rivista viene diffusa in Retro Riviste Retro Using formato PDF via Inter- Nibble Magazine, 28 Un MAC SE/30 resuscita, 60 net. Il costo di un singolo numero è di Euro 2. Abbonamento annuale (6 Una visita a... Biblioteca numeri) Euro 6. Marzaglia - maggio 2007, 32 Il nuovo manuale Z80, 62 Arretrati Euro 2 a numero. BBS Contatti Posta, 64 [email protected] Laboratorio 200 modi per resuscitare un HD Anteprima Copyright (parte 2), 34 I marchi citati sono di 66 copyrights dei rispettivi proprietari. La riproduzione con qual- siasi mezzo di illustrazioni e di articoli pubblicati sulla rivista, nonché la loro tra- duzione, è riservata e non può avvenire senza espres- In Copertina sa autorizzazione. -

Practical-Computing

REVIEWS Canon AS -100C BBC graphics packages Orion ,.J 1PrOVICA41AS:"E"E-Ticx. '1/474..1 .0.0c 4X Sy.u...:_-,4a.sosirN3 Stec o. Cromemco System One MicroCentre introduce Cromemco's newSystem One computer, available with an integral 5 megabyteWinchester hard disk, at a new low price. The System One supports thefull range of Cromemco interfacecards, including high resolution colourgraphics, and software packages. The choice of operating systemsincludes CDOS, CP/M and CROMIX Cromemco's answer toUnix. Call MicroCentrefor Q Cromemco 30 Dundas Street MicroCentre Ltd Britain's independent Edinburgh EH3 6JN Cromemco importer (Complete Micro Systems) Tel: 031-556 7354 Circle No. 101 PRACTICAL COMPUTING MAY 1983 DATABASED 1842ATARI BOOKS 128CHARITY *a BY THE DOZEN >NEWS How the National Association for Twelve books that set out to tell you SOFTWARE NEWS Gifted Children uses a database to what Atari doesn't tell you. 21New packages and other keep in touch with its members announcements. around the country. >FEATURES 2.2HARDWARE NEWS %IP What's happening in the >REV I EWS INTERVIEW personal -computer world. ihi MARTIN HEALEY 7aCANON AS -100C Strong views on operating systems IBM PC NEWS WI NEW FROM JAPAN and the future of the British micro 29"Big Blue" launches The editor tried out the latest IBM - from the man who designed the a go -faster version of the PC; plus PC work -alike. Find out why he Orion. more newly announced software. cried when they came and took it away. ROBOT PING-PONG 3.2DIARY 99John Billingsley of Li Forthcoming events, 8/TEXET'S LOW -PRICE Micromouse fame introduces a exhibitions and conferences. -

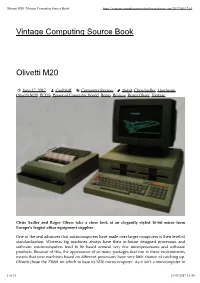

Olivetti M20 | Vintage Computing Source Book

Olivetti M20 | Vintage Computing Source Book https://vintagecomputingsourcebook.wordpress.com/2017/06/17/ol... Vintage Computing Source Book Olivetti M20 June 17, 2017 Godbluff Computer Review 16-bit, Chris Sadler, Hardware, Olive i M20, PCOS, Personal Computer World, Retro, Review, Roger Oliver, Vintage Chris Sadler and Roger Oliver take a close look at an elegantly styled 16-bit micro from Europe’s largest office equipment supplier. One of the real advances that microcomputers have made over larger computers is their level of standardisation. Whereas big machines always have their in-house designed processors and software, microcomputers tend to be based around very few microprocessors and software products. Because of this, the appearance of so many packages that run in these environments means that new machines based on different processors have very li le chance of catching up. Olive i chose the Z8001 on which to base its M20 microcomputer. As it isn’t a minicomputer in 1 of 13 11/07/2017 11:44 Olivetti M20 | Vintage Computing Source Book https://vintagecomputingsourcebook.wordpress.com/2017/06/17/ol... a micro box (like the Onyx), Olive i decided to write its own operating system, although, as a concession to the rest of the micro world, it offers the mandatory Microsoft Basic. On an unusual machine the question must be whether it has sufficient features over a more standard system to make it worth having. Hardware The Olive i M20 comes packaged in two detachable units, the main box and the monitor box. The main box houses the main board, a power supply and fan, the keyboard, and (on the review machine) a couple of disk drives. -

Retromagazine 02 Eng.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS Holiday time, memory time... ◊ The Olivetti M20 and the history of a Pag. 3 website Summer, with its torrid heat and hot nights came to visit all of us again. Probably now more than ever warmth and ◊ The LM80C Colour Computer - Part 1 Pag. 7 temperatures above average have been expected with such ◊ Japan 12th episode: Game & Watch Vs Pag. 11 trepidation. After a horrible winter and spring, this summer MADrigal is not only synonymous with holidays, but also a slow ◊ Can we multiply the number of games Pag. 18 return to the normal life for some of us. for THEC64? Yes, we can! ◊ Back to the past... - Episode nr. 2: Pag. 19 Who’s writing have been living abroad for few years now Windows 2000 and summer is one of the most awaited moments to be able to return to Italy and embrace friends and family. This year ◊ Amstrad CPC - Redefining characters Pag. 21 you can easily imagine how ardently I was waiting for the ◊ A splash screen in SCR format for the Pag. 23 possibility to travel again and return to the places of my Amstrad CPC youth. For those who live far from their home country the ◊ Abbreviations & shortcuts on using a Pag. 27 chance to return once or twice a year is like browsing graphical interface through a memory album. Finding places and people you ◊ The 1st RMW 8-bit Home Computer Pag. 30 haven't seen in a long time makes you want to know what Chess Tournament happened in the meantime and likewise the possibility of ◊ Introduction to ARexx – Part 1 Pag. -

Quaderni Di Storia Economica (Economic History Working Papers)

Quaderni di Storia Economica (Economic History Working Papers) European Acquisitions in the United States: Re-examining Olivetti-Underwood Fifty Years Later by Federico Barbiellini Amidei, Andrea Goldstein and Marcella Spadoni March 2010 number 2 Quaderni di Storia Economica (Economic History Working Papers) European Acquisitions in the United States: Re-examining Olivetti-Underwood Fifty Years Later by Federico Barbiellini Amidei, Andrea Goldstein and Marcella Spadoni Number 2 – March 2010 The purpose of the Economic History Working Papers (Quaderni di Storia economica) is to promote the circulation of preliminary versions of working papers on growth, finance, money, institutions prepared within the Bank of Italy or presented at Bank seminars by external speakers with the aim of stimulating comments and suggestions. The present series substitutes the Historical Research papers - Quaderni dell'Ufficio Ricerche Storiche. The views expressed in the articles are those of the authors and do not involve the responsibility of the Bank. Editorial Board: MARCO MAGNANI, FILIPPO CESARANO, ALFREDO GIGLIOBIANCO, SERGIO CARDARELLI, ALBERTO BAFFIGI, FEDERICO BARBIELLINI AMIDEI, GIANNI TONIOLO. Editorial Assistant: ANTONELLA MARIA PULIMANTI. ISSN 2281-6089 (print) ISSN 2281-6097 (online) European Acquisitions in the United States: Re-examining Olivetti-Underwood Fifty Years Later Federico Barbiellini Amidei , Andrea Goldstein and Marcella Spadoni Abstract While Italy’s catch-up in the course of the 20th century has been nothing short of extraordinary, it has failed to produce a large number of global business players. Nonetheless, half a century ago an Italian company concluded what was at the time the largest-ever foreign takeover of a US company. The paper analyzes the Olivetti’s acquisition of Underwood and frames it in the broader picture of the literature on the management and performance of foreign companies in the United States. -

Il BASIC Nei Personal E Home Computer Dal 1975 Al 1984

Il BASIC nei personal e home computer dal 1975 al 1984 Schede Tecniche Storia dell’Informatica a.a 2015/2016 Romano Ceccatelli - hmr.di.unipi.it/Corso 1/37 MITS Altair 8800 Il MITS Altair 8800 è stato uno tra i primi microcomputer disponibili sul mercato. È stato sviluppato e commercializzato dalla Micro Instrumentation & Telemetry Systems, Inc. (MITS), azienda con sede ad Albuquerque (Nuovo Messico, USA). Era dotato di un'interfaccia basata su interruttori (24). Agendo su di essi si può programmare in codice binario, mentre il risultato delle elaborazioni viene visualizzato tramite il lampeggio dei LED (36) posti sul pannello frontale. Esso conteneva appunto 36 LED: 16 per il bus degli indirizzi, 8 per i dati, 8 per lo stato e i restanti erano usati per visualizzare lo stato della CPU. C’erano, inoltre, una serie di interruttori per inserire gli indirizzi e i dati, oltre ad un insieme di interruttori per il controllo del sistema. Bill Gates e Paul Allen decisero di scrivere un linguaggio di programmazione per far funzionare l'Altair. Il risultato fu una versione semplificata del BASIC chiamata Altair BASIC. Poiché diverse parti elettroniche non erano ancora disponibili al momento della progettazione, e per risolvere i problemi di NOME MITS Altair 8800 dimensione della scheda madre, fu necessario inventare un apposito connettore, oggi noto come bus: questa nuova struttura di AZIENDA E LUOGO MITS DI PRODUZIONE Albuquerque Nuovo trasferimento dati divenne in seguito uno standard, chiamato S- Messico USA 100. Con questo accorgimento fu possibile spostare parte della logica dalla scheda madre su altre schede, con cui comunicava ANNO 1975 tramite il bus. -

Visualizza Il Libro in PDF Sulla Storia Della Famiglia

LAVORO ... coraggio e successo MARAZZATO una famiglia, un’azienda, tanto lavoro e una storia A nostro nonno Lucillo, ai nostri genitori Carlo e Mara, e a tutti quei collaboratori che, con il loro aiuto e lavoro, ci hanno permesso di realizzare tutto questo. Alberto, Luca e Davide. Te s t i e coordinamento editoriale: Valentina Masotti Impaginazione, stampa e legatura: GALLO artigrafiche, Vercelli © Gruppo Marazzato Borgovercelli Giugno 2013 LAVORO... coraggio e successo MARAZZATO una famiglia, un’azienda, tanto lavoro e una storia Lavoro, coraggio e successo 1919La storia della famiglia Marazzato. 2013 Il mio sogno nel cassetto è sempre stato quello di scrivere un libro che rievocasse la storia Una famiglia, della mia famiglia e dell’azienda che mio nonno Lucillo fondò nel secondo dopo guerra. Mi un’azienda, affascinavano gli aneddoti che raccontava durante i pranzi di famiglia o semplicemente tanto lavoro quando faceva un salto in ufficio a salutarmi. C’era sempre una morale, una lezione da e... una storia imparare dalle sue esperienze di vita. Un po’ per pigrizia, un po’ per mancanza di tempo, negli anni l’idea del libro fu dimenticata in un cassetto insieme allo scatolone di foto, alle cambiali degli anni cinquanta che portavano la sua firma, ai registri di contabilità ancora compilati a mano con calligrafia. Dopo la morte del nonno, mio padre ha conservato tutti quei ricordi nel suo ufficio. Così quest’anno mi sono deciso a raccogliere tutto il materiale necessario a pubblicare la storia della Marazzato. Non mi aspettavo davvero che l’impresa avrebbe suscitato tanto entusiasmo in famiglia: è emersa da parte di ciascuno una voglia di raccontare, di ricor- dare, di ricercare fatti nella memoria e cimeli in fondo agli armadi che andava oltre alle mie speranze. -

Catalogo Degli Accessori Elettrici Ed Elettronici (Come Le Piste Per Le Macchinine)

Museo del Calcolatore “Laura Tellini” La storia dell’Informatica a contatto con la nostra vita Istituto Tecnico Economico e Professionale Statale “Paolo Dagomari” Via di Reggiana, 86 – Prato Tel. 0574-639705 [email protected] http://museo.dagomari.prato.it https://www.facebook.com/groups/museo.dagomari/ Il Museo del Calcolatore, premessa Il “Museo del Calcolatore” del Dagomari è dedicato alla prof.ssa La passione per i vecchi calcolatori nacque, quasi per gioco, nel 1996; all'epoca, nella scuola in cui insegno Informatica dal 1987, Laura Tellini, insegnante di questa scuola, che ci ha lasciato prema- cercavamo insieme ad una quinta classe un argomento che potesse turamente: il suo ultimo pensiero «…il museo non ho dubbi che abbinare tecnologia, storia e scienze matematiche, da sviluppare verrà perfetto», sia di stimolo per migliorarci continuamente nella per l'esame di stato. nostra missione. La scelta ricadde sulla realizzazione di un sito web che ricor- dasse gli avvenimenti più importanti della storia del calcolo: chia- mammo il lavoro "Museo virtuale del computer". Fu appassionante per me e per gli studenti percorrere a ritroso la storia dell'umanità, Con il patrocinio di: alla ricerca dei pionieri che con le loro intuizioni avevano contribuito allo sviluppo dei calcolatori come li intendiamo oggi. Successivamente, appassionatomi all'argomento, ho iniziato, Si ringraziano, per il loro prezioso contributo all’allestimento del Museo: Asia Martini, Yuri Bonari, un po' alla volta, ad incrementare il materiale virtualmente esposto; Lorenzo Stolfi, Pierluigi Galgani, Terzo Nicolai, Lorenzo Galloni, Giovanni Fiesoli, Mauro Gasparini, ma mancava sempre qualcosa di tangibile, da poter mostrare o Stefano Landi, Luigi Ricci, Paolo Artini, Liana Parrini, Rolando Aliani, Cristian Martini, Daniele Giovannini, Riccardo Aliani, Maurizio Santini, Roberto Sardi, Andrea Mazzoni, Paolo Russo, Antonella Solano, addirittura far usare alle giovani generazioni. -

VCFI 2019 Brochure Lowres

2019 Roma 27 e 28 aprile Complesso Ex Cartiera Latina Via Appia Antica, 42 La più grande manifestazione sulla storia del personal computer Esposizione di PC d’epoca, raduno di collezionisti e appassionati, incontri, workshop e conferenze con i protagonisti del mondo dell’informatica. Powered by IDEA Il nostro scopo è quello di mantenere, promuovere e diffondere la storia di Personal Computer, con particolare attenzione dagli anni ’60 agli anni ’90. Quegli anni in cui tutto è cambiato e il computer è passato dall'essere un vantaggio per pochi a un beneficio per tutti. VINTAGE COMPUTER FESTIVAL ITALIA 2019 “ Focus: come il personal computer ha cambiato l’insegnamento e l’apprendimento” LOCATION Ex Cartiera Latina. La ex Cartiera Latina, tra i pochi impianti industriali sopravvissuti nella città di Roma, è una struttura unica nel suo genere ed eccezionale per la posizione strategica a ridosso delle Mura Aureliane. Oggi il complesso multifunzionale è gestito dall’Ente Parco Appia Antica, è dotato di due sale per esposizioni (Nagasawa e Appia) e una Sala Conferenze; una biblioteca; uno spazio didattico espositivo naturalistico, “Dì Natura”, dove si svolgono attività per le scuole e le famiglie e dove è presente un Punto Info con Bookshop. Uno spazio verde esterno attrezzato che ospita l’orto didattico “Hortus Urbis”, un'area didattica dedicata alle tradizioni della Campagna Romana ed una area attrezzata per la sosta. A CHI SI RIVOLGE IL VCFI Il Vintage Computer Festival Italia è per tutti coloro che amano il computer e la sua evoluzione. Dagli -

Retrocomputer Magazine

Jurassic News in questo numero parliamo di: Victor 1 Honeywell kitchen computer Vincenzo Scarpa Steve Jobs Windows 98 SNOBOL Q-Emulator Storie di Commodore 300 baud magazine Spectrum Vega+ Retrocomputer Magazine Anno 11 - Numero 58 - Aprile 2016 Jurassic News Rivista aperiodica di Retrocomputer Jurassic News Coordinatore editoriale: Tullio Nicolussi [Tn] E’ una fanzine dedicata al retro- Redazione: computing nella più ampia accezione del [email protected] termine. Gli articoli trattano in generale dell’informatica a partire dai primi anni Hanno collaborato a questo numero: Lorenzo [L2] ‘80 e si spingono fino ...all’altro ieri. Salvatore Macomer [Sm] La pubblicazione ha carattere Sonicher [Sn] puramente amatoriale e didattico, tutte Besdelsec [Bs] Lorenzo Paolini [Lp] le informazioni sono tratte da materiale Mario Raspanti originale dell’epoca o raccolte su Internet. Fabio [Ft] Damiano Cavicchio La redazione e gli autori degli articoli non si assumono nessuna responsabilità in merito alla correttezza Diffusione: delle informazioni riportate o nei Lettura on-line sul sito o attraverso il servizio Issuu.com; il download è confronti di eventuali danni derivanti disponibile per gli utenti registrati. dall’applicazione di quanto appreso sulla rivista. Sito Web: www.jurassicnews.com Il contenuto degli articoli è frutto delle conoscenze, esperienze personali e opinioni dei singoli autori; possono Contatti: [email protected] pertanto essere talvolta non precise o differire da fonti “ufficiose” come Copyright: Wikipedia e siti Web specializzati. I marchi citati sono di copyrights dei rispettivi proprietari. Sono gradite segnalazioni di errori, La riproduzione con qualsiasi imprecisioni o errate informazioni che mezzo di illustrazioni e di articoli possono, a discrezione della redazione, pubblicati sulla rivista, nonché essere oggetto di errata-corrige in la loro traduzione, è riservata e non può avvenire senza espressa fascicoli successivi.