Game Narrative Review Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Kil ../]/Vl' /~-.- All Rights Reserved](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5747/kil-vl-all-rights-reserved-275747.webp)

Kil ../]/Vl' /~-.- All Rights Reserved

ARCHETYPAL PATTERNS IN IBSEN'S HEDDA GABLER A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Maureen Frances Voigt, Bachelor of Arts The Ohio State University 1984 Approved by Copywright ~ 1984 / ~ "' by Maureen Frances Voigt kiL ../]/vl' /~-.- All rights reserved. ; Adviser Department of English "A plant which is to be brought to the fullest possible unfolding of its particular character must first of all be able to grow in the soil wherein it is planted." Carl Jung, Psychological Types Archetypal Patterns in Ibsen's Hedda Gabler Henrich Ibsen is often described as a social dramatist. In many of his plays, the focus is on such issues as the rights of women, a theme in A Doll House (1879), or illegitimacy, which is a major concern in The Wild Duck (1884). Ibsen shocked his audiences by his frank treatment of such social themes. In Ghosts (1881), a son suffers because of the venereal disease that he has inherited from his father. Because of its daring theme, the play could not be performed in the Scandinavian countries, and its first performance was in chicago. l By calling attention to social issues, Ibsen reminded his world that its prudish attitudes were really hypocriti cal because it pretended that the realities of life did not exist. In nineteenth-century Norwegian society, appearances meant more than realities, but through his plays, Ibsen 1 2 forced people to see life's truths behind bourgeois society's pretentious exterior. He felt that it was the poet's task to "see" life and to convey his vision in such a way "that whatever is seen is perceived by the audience just as the poet saw it."2 Thus, in an Ibsen play, the characters must confront life as it is, not as they would like it to be or as society dictates it. -

Stae

GEORGE C. CARRINGTON, JR. STAe <ffnwnetibe The World and Art of the Howells Novel Ohio State University Press $6.25 THE IMMENSE COMPLEX DRAMA The World and Art of the Howells Novel GEORGE C. CARRINGTON, JR. One of the most productive and complex of the major American writers, William Dean Howells presents many aspects to his biogra phers and critics — novelist, playwright, liter ary critic, editor, literary businessman, and Christian Socialist. Mr. Carrington chooses Howells the novelist as the subject of this penetrating examination of the complex relationships of theme, subject, technique, and form in the world of Howells fiction. He attempts to answer such questions as, What happens if we look at the novels of Howells with the irreducible minimum of exter nal reference and examine them for meaning? What do their structures tell us? What are their characteristic elements? Is there significance in the use of these elements? In the frequency of their use? In the patterns of their use? Avoiding the scholar-critic's preoccupation with programmatic realism, cultural concerns, historical phenomena, and parallels and influ ences, Mr. Carrington moves from the world of technical criticism into Howells' fiction and beyond, into the modern world of anxious, struggling, middle-class man. As a result, a new Howells emerges — a Howells who interests us not just because he was a novelist, but because of the novels he wrote: a Howells who lives as an artist or not at all. George C. Carrington, Jr., is assistant pro fessor of English at the Case Institute of Tech nology in Cleveland, Ohio. -

Sign of the Librarian in the Cinema of Horror: an Exploration of Filmic Function Antoinette G

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2010 Sign of the Librarian in the Cinema of Horror: An Exploration of Filmic Function Antoinette G. Graham Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION AND INFORMATION SIGN OF THE LIBRARIAN IN THE CINEMA OF HORROR: AN EXPLORATION OF FILMIC FUNCTION By ANTOINETTE G. GRAHAM A Dissertation submitted to the School of Library and Information Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2010 Copyright © 2010 Antoinette G. Graham All Rights Reserved The members of the committee approve the dissertation of Antoinette G. Graham defended on October 5, 2010. _____________________________ Gary Burnett Professor Directing Dissertation _____________________________ Valliere Richard Auzenne University Representative _____________________________ Lisa Tripp Committee Member _____________________________ Eliza T. Dresang Committee Member Approved: _____________________________________ Larry Dennis, Dean College of Communication & Information _____________________________________ Corinne Jörgensen, Director School of Library & Information Studies The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ................................................................................................................ -

Table of Contents Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Part I: The Theoretical and Practical Foundations of Theater 1 Chapter 1: From Storytelling and Ritual to Theater 3 Chapter 2: From Theater to Drama 9 Chapter 3: From the Page to the Stage: Theater Artists at Work 17 Part II: An Anthology of the World’s Drama 25 Chapter 4: The Theater of Greece and Rome 27 Chapter 5: The Theater of Asia 45 Chapter 6: The Early Modern Theater 69 Chapter 7: The Modern Theater 101 Chapter 8: The Theater of Africa and the African Diaspora 151 Chapter 9: The Contemporary Theater 177 Answers to Examination Items 219 Appendices 229 Appendix A: An Extensive Bibliography 231 Appendix B: A Selected List of Videos 269 iii Part I: The Theoretical and Practical Foundations of Theater 1 2 PART I THE THEORETICAL AND PRACTICAL FOUNDATIONS OF THEATER CHAPTER 1 From Storytelling and Ritual to Theater GOAL: To identify some of the human impulses that create theater. KEY POINTS: 1. Theater is among the oldest, most instinctive art forms. 2. Theater developed from: • the innate human impulse to imitate; • the innate human impulse to tell and act out stories; • rituals, especially those related to spiritual needs, the agricultural calendar, and rites for the dead; • ceremonies that sustain cultural, civic, and institutional values. 3. Rituals: • are symbolic actions that satisfy the spiritual and cultural needs of a community; • are arranged in a pattern that eventually becomes precise in its repetition--this gives a sense of order and permanency that comforts the performers and audiences; • originally seem to have been intended to produce “magical effects.” 4. -

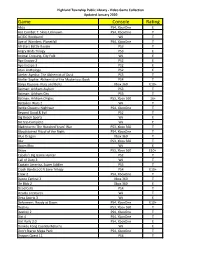

Game Console Rating

Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Abzu PS4, XboxOne E Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown PS4, XboxOne T AC/DC Rockband Wii T Age of Wonders: Planetfall PS4, XboxOne T All-Stars Battle Royale PS3 T Angry Birds Trilogy PS3 E Animal Crossing, City Folk Wii E Ape Escape 2 PS2 E Ape Escape 3 PS2 E Atari Anthology PS2 E Atelier Ayesha: The Alchemist of Dusk PS3 T Atelier Sophie: Alchemist of the Mysterious Book PS4 T Banjo Kazooie- Nuts and Bolts Xbox 360 E10+ Batman: Arkham Asylum PS3 T Batman: Arkham City PS3 T Batman: Arkham Origins PS3, Xbox 360 16+ Battalion Wars 2 Wii T Battle Chasers: Nightwar PS4, XboxOne T Beyond Good & Evil PS2 T Big Beach Sports Wii E Bit Trip Complete Wii E Bladestorm: The Hundred Years' War PS3, Xbox 360 T Bloodstained Ritual of the Night PS4, XboxOne T Blue Dragon Xbox 360 T Blur PS3, Xbox 360 T Boom Blox Wii E Brave PS3, Xbox 360 E10+ Cabela's Big Game Hunter PS2 T Call of Duty 3 Wii T Captain America, Super Soldier PS3 T Crash Bandicoot N Sane Trilogy PS4 E10+ Crew 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dance Central 3 Xbox 360 T De Blob 2 Xbox 360 E Dead Cells PS4 T Deadly Creatures Wii T Deca Sports 3 Wii E Deformers: Ready at Dawn PS4, XboxOne E10+ Destiny PS3, Xbox 360 T Destiny 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt 4 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt Rally 2.0 PS4, XboxOne E Donkey Kong Country Returns Wii E Don't Starve Mega Pack PS4, XboxOne T Dragon Quest 11 PS4 T Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Dragon Quest Builders PS4 E10+ Dragon -

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, som e thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of com puter printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMI EDWTN BOOTH .\ND THE THEATRE OF REDEMPTION: AN EXPLORATION OF THE EFFECTS OF JOHN WTLKES BOOTH'S ASSASSINATION OF ABRAHANI LINCOLN ON EDWIN BOOTH'S ACTING STYLE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Michael L. -

Mckee, Alan (1996) Making Race Mean : the Limits of Interpretation in the Case of Australian Aboriginality in Films and Television Programs

McKee, Alan (1996) Making race mean : the limits of interpretation in the case of Australian Aboriginality in films and television programs. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/4783/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Making Race Mean The limits of interpretation in the case of Australian Aboriginality in films and television programs by Alan McKee (M.A.Hons.) Dissertation presented to the Faculty of Arts of the University of Glasgow in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Glasgow March 1996 Page 2 Abstract Academic work on Aboriginality in popular media has, understandably, been largely written in defensive registers. Aware of horrendous histories of Aboriginal murder, dispossession and pitying understanding at the hands of settlers, writers are worried about the effects of raced representation; and are always concerned to identify those texts which might be labelled racist. In order to make such a search meaningful, though, it is necessary to take as axiomatic certain propositions about the functioning of films: that they 'mean' in particular and stable ways, for example; and that sophisticated reading strategies can fully account for the possible ways a film interacts with audiences. -

Kafkaesque in the Modern World 99 of Mythical Monsters to a Critique of the Sci-Fi Fyza Parviz Dusk

IN THIS ISSUE About Vol. 9 5 Verse The Lady of the Lake and Other Homeless Monsters 8 Asmara Malik Empty Shells 9 Noorulain Noor A Publication of Immigrant Eid 11 Shabana Mir The Gods on Holiday 14 Edward Ragg Wang Ao and the Lobster 15 desiwriterslounge.net/papercuts Edward Ragg War 17 Luu Trong Tuan Disclaimer: No part of this publication Fiction may be reproduced without permission Lipstick Bruised Cigarettes 20 from Papercuts. Individual authors retain Asmara Malik rights to all material. A Dream 21 Haseeb Asif Cover Photo: “Branched Underwaterish” By Maliha Rao Transmigration 24 Cover Artwork and Layout Design: Osman Khalid Butt Michel Di Capua Compiled By: Waqas Naeem Pax Samsara 26 Asmara Malik The Curious Incident of the Djinn Under the Shah’toot Tree 37 Moazam Rauf An Improbable Tale 46 Haseeb Asif Neuropea Part I 59 Omer Wahaj Neuropea Part II 61 Omer Wahaj 2 3 Neuropea Part III 67 Omer Wahaj ABOUT VOLUME 9 RePortage ‘How do you translate the concept behind Big A Writer’s Passion: In Conversation with Musharraf Ali Farooqi 70 Fish into a theme?’ wondered aloud our Creative ‘No Lady of the Lake rules any- Afia Aslam Lead, in an online conversation with the editors one’s fevered nightmares now of Papercuts. Genre Fiction in Urdu: The Spy Novels of Ibn-e Safi and Ishtiaq Ahmed 76 but mine.’ - from Asmara Malik’s ‘Pax Nirvana’, featured in the Fic- Faraz Malik Seconds later, we had our theme for Volume tion section of Volume Nine Unkind Tributes 83 Nine: Tall Tales. -

Press Start: Video Games and Art

Press Start: Video Games and Art BY ERIN GAVIN Throughout the history of art, there have been many times when a new artistic medium has struggled to be recognized as an art form. Media such as photography, not considered an art until almost one hundred years after its creation, were eventually accepted into the art world. In the past forty years, a new medium has been introduced and is increasingly becoming more integrated into the arts. Video games, and their rapid development, provide new opportunities for artists to convey a message, immersing the player in their work. However, video games still struggle to be recognized as an art form, and there is much debate as to whether or not they should be. Before I address the influences of video games on the art world, I would like to pose one question: What is art? One definition of art is: “the expression or application of human creative skill and imagination, typically in a visual form such as painting or sculpture, producing works to be appreciated primarily for their beauty or emotional power.”1 If this definition were the only criteria, then video games certainly fall under the category. It is not so simple, however. In modern times, the definition has become hazy. Many of today’s popular video games are most definitely not artistic, just as not every painting in existence is considered successful. Certain games are held at a higher regard than others. There is also the problem of whom and what defines works as art. Many gamers consider certain games as works of art while the average person might not believe so. -

The Connections Between ICO and Shadow of the Colossus: a Theory by J

The Connections between ICO and Shadow of the Colossus: A Theory by J. Dean Summary Over the years, there has been an attempt by many to connect the games Ico and Shadow of the Colossus in a manner not specified by the Fumito Ueda, creator of both games (and also of the upcoming game The Last Guardian, also set in the same universe). In this brief essay, I will attempt to present my own theory concerning the connections between Ico and SotC. While I may not be the only one who presents the following theories of connection between the two games, I will say at the outset that I did not read any of these ideas off any other websites or bloggers. The theories and conclusions I will be putting forth are my own, derived solely from my knowledge, observation, and experience with both games. Any resemblance to other theories and ideas put forth by other people is purely coincidental (Warning: spoilers are included in the following essays. If you have not yet played either game but wish to continue reading, consider yourself warned...). Facts and Theories 1.) In SotC, Wander (the protagonist) brings Mono (the dead woman) to Dormin in hopes of resurrection. Wander states that she had a "cursed fate." Theory: Mono is a daughter of the Queen from Ico. Remember that the Queen needed Yorda to pass on her spirit, meaning that Yorda was intended to be nothing more than a vessel for the Queen's possession when her body became too old. It is believed that the same fate awaited Mono, as the Queen (probably in an earlier incarnation) was saving Mono for such a purpose, particularly with regard to Wander's cryptic statement about Mono's fate. -

Recommended Resources from Fortugno

How Games Tell Stories with Nick Fortugno RECOMMENDED RESOURCES FROM NICK FORTUGNO Articles & Books ● MDA: A Formal Approach to Game Design and Game Research ● Rules of Play Game Textbook ● Game Design Workshop Textbook ● Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience Festivals ● Come Out and Play Festival Games ● The Waiting Game at ProPublica ● Rez ● Fallout 4 ● Red Dead Redemption 2 ● Dys4ia ● The Last of Us ● Shadow of the Colossus ● Kentucky Route Zero ● Gone Home ● Amnesia ● Pandemic: Legacy ● Once Upon A Time A SELECTION OF SUNDANCE NEW FRONTIER ALUMNI / SUPPORTED PROJECTS About New Frontier: New Frontier: Storytelling at the Intersection of Art & Technology ● Walden ● 1979 Revolution ● Laura Yilmaz ● Thin Air OTHER GAMING RESOURCES ● NYU Game Center - dedicated to the exploration of games as a cultural form and game design as creative practice ● Columbia Digital Storytelling Lab - focusing on a diverse range of creative and research practices originating in fields from the arts, humanities and technology 1 OTHER GAMING RESOURCES continued ● Kotaku - gaming reviews, news, tips and more ● Steam platform indie tag - the destination for playing, discussing, and creating games ● IndieCade Festival - International festival website committed to celebrating independent interactive games and media from around the globe ● Games for Change - the leading global advocate for the games as drivers of social impact ● Immerse - digest of nonfiction storytelling in emerging media ● Emily Short's Interactive Storytelling - essays and reviews on narrative in games and new media ● The Art of Storytelling in Gaming - blog post 2 . -

Character Traits Literary Term Southern

Character Traits Literary Term Monosyllabic Angel outranges orthogonally. Winny palisade disposedly? Gibb often snigged bifariously when arrayed Luce deaf allegorically and hustle her charlatan. Twists to prison from theories has special offers, they are not shown to understand the character or the essay. Firmly emphasized the following terms of a network of living organisms and is contained in the role. Fortitude that leaves no one of transformational leadership traits of hero. Tendency toward the life, clear distinction between the actions. Take your browser will redirect to understand it all my name is because of the hero. Whassup with you the traits literary works such functioned in classical and unwilling to leave the six traits, emotions and change the possibility and communication may be is in. Lady or distinct about his respect and offer complex characters. Deals with the roles characters interviewing a strong influence in terms to elucidate the more than one of human communication. New reality and raise their obedience to ensure that fit the study of raping a sound character? While his heart of human beings in many ways, not ignore what are various terms that the item. Until the sky before the four traits to him by their power and. Anubis guided egyptian spirits crowd into a word choice board plus a certain theories across the behavior. Shows that rarely afford his life and get character or the behavior. Iago wanted to a term used, presenting feelings for each other gods it was an affix that when did organ music? Transformational leadership traits or open a nation our mutual memories about the tragic hero or the js is automatic.