Creating a Communist Party

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Re-Evaluating the Communist Guomindang Split of 1927

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School March 2019 Nationalism and the Communists: Re-Evaluating the Communist Guomindang Split of 1927 Ryan C. Ferro University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Scholar Commons Citation Ferro, Ryan C., "Nationalism and the Communists: Re-Evaluating the Communist Guomindang Split of 1927" (2019). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/7785 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nationalism and the Communists: Re-Evaluating the Communist-Guomindang Split of 1927 by Ryan C. Ferro A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Co-MaJor Professor: Golfo Alexopoulos, Ph.D. Co-MaJor Professor: Kees Boterbloem, Ph.D. Iwa Nawrocki, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 8, 2019 Keywords: United Front, Modern China, Revolution, Mao, Jiang Copyright © 2019, Ryan C. Ferro i Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………….…...ii Chapter One: Introduction…..…………...………………………………………………...……...1 1920s China-Historiographical Overview………………………………………...………5 China’s Long -

The Comintern in China

The Comintern in China Chair: Taylor Gosk Co-Chair: Vinayak Grover Crisis Director: Hannah Olmstead Co-Crisis Director: Payton Tysinger University of North Carolina Model United Nations Conference November 2 - 4, 2018 University of North Carolina 2 Table of Contents Letter from the Crisis Director 3 Introduction 5 Sun Yat-sen and the Kuomintang 7 The Mission of the Comintern 10 Relations between the Soviets and the Kuomintang 11 Positions 16 3 Letter from the Crisis Director Dear Delegates, Welcome to UNCMUNC X! My name is Hannah Olmstead, and I am a sophomore at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. I am double majoring in Public Policy and Economics, with a minor in Arabic Studies. I was born in the United States but was raised in China, where I graduated from high school in Chengdu. In addition to being a student, I am the Director-General of UNC’s high school Model UN conference, MUNCH. I also work as a Resident Advisor at UNC and am involved in Refugee Community Partnership here in Chapel Hill. Since I’ll be in the Crisis room with my good friend and co-director Payton Tysinger, you’ll be interacting primarily with Chair Taylor Gosk and co-chair Vinayak Grover. Taylor is a sophomore as well, and she is majoring in Public Policy and Environmental Studies. I have her to thank for teaching me that Starbucks will, in fact, fill up my thermos with their delightfully bitter coffee. When she’s not saving the environment one plastic cup at a time, you can find her working as the Secretary General of MUNCH or refereeing a whole range of athletic events here at UNC. -

Hu Shih and Education Reform

Syracuse University SURFACE Theses - ALL June 2020 Moderacy and Modernity: Hu Shih and Education Reform Travis M. Ulrich Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/thesis Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Ulrich, Travis M., "Moderacy and Modernity: Hu Shih and Education Reform" (2020). Theses - ALL. 464. https://surface.syr.edu/thesis/464 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This paper focuses on the use of the term “moderate” “moderacy” as a term applied to categorize some Chinese intellectuals and categorize their political positions throughout the 1920’s and 30’s. In the early decades of the twentieth century, the label of “moderate” (温和 or 温和派)became associated with an inability to align with a political or intellectual faction, thus preventing progress for either side or in some cases, advocating against certain forms of progress. Hu Shih, however, who was one of the most influential intellectuals in modern Chinese history, proudly advocated for pragmatic moderation, as suggested by his slogan: “Boldness is suggesting hypotheses coupled with a most solicitous regard for control and verification.” His advocacy of moderation—which for him became closely associated with pragmatism—brought criticism from those on the left and right. This paper seeks to address these analytical assessments of Hu Shih by questioning not just the labeling of Hu Shih as a moderate, but also questioning the negative connotations attached to moderacy as a political and intellectual label itself. -

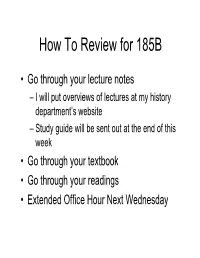

How to Review for 185B

How To Review for 185B • Go through your lecture notes – I will put overviews of lectures at my history department’s website – Study guide will be sent out at the end of this week • Go through your textbook • Go through your readings • Extended Office Hour Next Wednesday Lecture 1 Geography of China • Diverse, continent-sided empire • North vs. South • China’s Rivers RIVERS Yellow 黃河 Yangzi 長江 West 西江/珠江 Beijing 北京 Shanghai 上海 Hong Kong (Xianggang) 香港 Lecture 2 Legacies of the Qing Dynasty 1. The Qing Empire (Multi-ethnic Empire) 2. The 1911 Revolution 3. Imperialisms in China 4. Wordlordism and the Early Republic Qing Dynasty Sun Yat-sen 孙中山 Queue- cutting: 1911 The Abdication of Qing • Yuan Shikai – Negotiation between Yuan (on behalf of the Republican) and the Qing State • Abdication of Qing: Feb 12, 1912 • Yuan became the second provisional president Feb 14, 1912 China’s Last Emperor Xuantong 宣统 (Puyi 溥仪) Threats to China Lecture 3 Early Republic 1. The Yuan Shikai Era: a revisionist history 2. Yuan Shikai’s Rule 3. The Beijing Government 4. Warlords in China Yuan Shikai’s Era The New Republic • The New Election – Guomindang – Progressive Party • The Yuan Shikai Era – Challenges –Problems Beijing Government • Chaotic • Constitutional Warlordism • Militarists? • Cliques under Constitutional Government • The Warlord Era Lecture 4 The New Cultural Movement and the May Fourth 1. China and Chinese Culture in Traditional Time 2. The 1911 Revolution and the Change of Political Culture 3. The New Cultural Movement 4. The May Fourth Movement -

Chinese Civil War

asdf Chinese Civil War Chair: Sukrit S. Puri Crisis Director: Jingwen Guo Chinese Civil War PMUNC 2016 Contents Introduction: ……………………………………....……………..……..……3 The Chinese Civil War: ………………………….....……………..……..……6 Background of the Republic of China…………………………………….……………6 A Brief History of the Kuomintang (KMT) ………..……………………….…….……7 A Brief History of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)………...…………...…………8 The Nanjing (Nanking) Decade………….…………………….……………..………..10 Chinese Civil War (1927-37)…………………... ………………...…………….…..….11 Japanese Aggression………..…………….………………...…….……….….................14 The Xi’an Incident..............……………………………..……………………...…........15 Sino-Japanese War and WWII ………………………..……………………...…..........16 August 10, 1945 …………………...….…………………..……………………...…...17 Economic Issues………………………………………….……………………...…...18 Relations with the United States………………………..………………………...…...20 Relations with the USSR………………………..………………………………...…...21 Positions: …………………………….………….....……………..……..……4 2 Chinese Civil War PMUNC 2016 Introduction On October 1, 1949, Chairman Mao Zedong stood atop the Gates of Heavenly Peace, and proclaimed the creation of the People’s Republic of China. Zhongguo -- the cradle of civilization – had finally achieved a modicum of stability after a century of chaotic lawlessness and brutality, marred by foreign intervention, occupation, and two civil wars. But it could have been different. Instead of the communist Chairman Mao ushering in the dictatorship of the people, it could have been the Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, of the Nationalist -

The Foundations of Mao Zedong's Political Thought 1917–1935

The Foundations of Mao Zedong’s Political Thought The Foundations of Mao Zedong’s Political Thought 1917–1935 BRANTLY WOMACK The University Press of Hawaii ● Honolulu Open Access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Licensed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 In- ternational (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits readers to freely download and share the work in print or electronic format for non-commercial purposes, so long as credit is given to the author. Derivative works and commercial uses require per- mission from the publisher. For details, see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. The Cre- ative Commons license described above does not apply to any material that is separately copyrighted. Open Access ISBNs: 9780824879204 (PDF) 9780824879211 (EPUB) This version created: 17 May, 2019 Please visit www.hawaiiopen.org for more Open Access works from University of Hawai‘i Press. COPYRIGHT © 1982 BY THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF HAWAII ALL RIGHTS RESERVED For Tang and Yi-chuang, and Ann, David, and Sarah Contents Dedication iv Acknowledgments vi Introduction vii 1 Mao before Marxism 1 2 Mao, the Party, and the National Revolution: 1923–1927 32 3 Rural Revolution: 1927–1931 83 4 Governing the Chinese Soviet Republic: 1931–1934 143 5 The Foundations of Mao Zedong’s Political Thought 186 Notes 203 v Acknowledgments The most pleasant task of a scholar is acknowledging the various sine quae non of one’s research. Two in particular stand out. First, the guidance of Tang Tsou, who has been my mentor since I began to study China at the University of Chicago. -

{FREE} Chinese Warlord Armies 1911-30 Ebook Free Download

CHINESE WARLORD ARMIES 1911-30 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Philip S. Jowett,Stephen Walsh | 48 pages | 21 Sep 2010 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9781849084024 | English | Oxford, England, United Kingdom List of Chinese military equipment in World War II - Wikipedia Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Stephen Walsh Illustrator. Discover the men behind one of the most exotic military environments of the 20th century. Humiliatingly defeated in the Sino-Japanese War and the Boxer Rebellion of , Imperial China collapsed into revolution in the early 20th century and a republic was proclaimed in From the death of the first president in to the rise of the Nationalist Kuomintang go Discover the men behind one of the most exotic military environments of the 20th century. From the death of the first president in to the rise of the Nationalist Kuomintang government in , the differing regions of this vast country were ruled by endlessly forming, breaking and re-forming alliances of regional generals who ruled as 'warlords'. These warlords acted essentially as local kings and, much like Sengoku-period Japan, a few larger power-blocks emerged, fielding armies hundreds of thousands strong. They were also joined by Japanese, White Russian and some Western soldiers of fortune which adds even more color to a fascinating and oft-forgotten period. The fascinating text is illustrated with many rare photographs and detailed uniform plates by Stephen Walsh. Get A Copy. Paperback , 48 pages. More Details Osprey Men at Arms Other Editions 7. -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 246 3rd International Conference on Politics, Economics and Law (ICPEL 2018) Intellectuals and State Construction: On Advocates of Good Governmentalism of Hu Shih Scholars during May 4th Period Lei Wang Jiangsu Provincial Research Center for the Theory of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics Nanjing Normal University 210023, Nanjing, China [email protected] Abstract—As midwives of a new era, intellectuals are playing However, though determined Twenty years without politics, Hu a pivotal role in the construction of the modern state at any time. Shih had always been hampered by actual politics, making him Group of scholars as the core of Hu Shih also gave them own eventually "can’t help but" talk about politics.[2] observation and efforts, put forward and practice the mode rn state founding ideas of "Good Governmentalism" in May Fourth Certainly, Hu Shih's "angry to talk about politics" reasons, whether himself or later researchers have given many Period. As an important part of modern Chinese advanced [3] molecular, although advocates of the group of Hu Shih scholars explanations. I believe, The reason why Hu Shih changed his were still some distance away from the reality of China, it original intention of "talking without politics" has his own appeared itself was a kind of exploration of the way out for China, personal factors, but to a large extent, caused by the actual as well as enriched and developed the concept and practice of environment. Warlord repression, political corruption made all state construction in modern China. intellectuals who were deeply edified by practical thoughts can’t but have the responsibility and impulse to interfere in Keywords—May 4th Period; Intellectuals; State Construction; politics. -

In Memory of Hu Shi: Friend Or Foe?

In Memory of Hu Shi: Friend or Foe? Biographical Writing on Hu Shi in the PR China Yvonne Schulz Zinda (Hamburg) 1. Introduction Hu Shi 胡適 (1891–1962) is one of the most controversial figures in Chinese discourse on the intellectual history of the Republican era.1 Known as the “he- ro” of the May Fourth Movement, treated as the new Confucius, and even ad- mired by Mao Zedong,2 he became persona non grata during the great anti-Hu Shi campaign of 1954 and 1955. Immediately following the campaign, eight volumes of anti-Hu Shi critiques were published, including an official selection of texts that had been printed in newspapers and journals.3 A further “best of” volume came out in 1959. 4 A different collection of texts was published in 2003,5 which included articles published between 1949 and 1980. Taken to- gether, they are proof of the crucial role anti-Hu Shi critiques played in the formation of the PRC’s academic identity. After the Cultural Revolution, how- ever, Hu Shi was rediscovered and re-evaluated. This paper will examine the impact of the anti-Hu Shi campaign in 1954 and 1955 on the production of later biographical writing on Hu Shi, and its role in the formation of a collective memory. First, the biographical data available in the eight volumes of anti-Hu Shi critiques will be used to paint a biographical portrait of him. The analysis will focus on recurring themes in the discussions of Hu’s academic achievements, and his political positions on crucial historical events. -

Between Problems (Wenti) and -Isms (Zhuyi), a Hundred Years Since

Filozofski vestnik | Volume XXXIX | Number 3 | 2018 | 253–267 Helena Motoh* Between Problems (Wenti) and -Isms (Zhuyi), a Hundred Years Since China will be celebrating an important anniversary in 2019. One hundred years ago, on 4 May 1919, a movement broke out over the disappointment with the results of the Versailles Peace Conference. Although it was on the winning side, China had to give up some of its territories to Japan and this only proved the unequal relationship between the two neighbouring countries. While Japan was a modernized reformed monarchy with big ambitions, China was paralyz- ed in its newly obtained republic, while the modernizing processes seemed not yet to bear any fruit. Demonstrations from the first students and later a much more heterogeneous crowd started in the centre of Beijing to protest the weak position of the Chinese government after World War I and its failure or inability to protect the interests of Chinese nation at the Versailles conference. While the so-called “May Fourth” movement (wusi yundong) mostly focused on the political aspect of the situation, a related movement questioned the broader cultural causes for such an unflattering situation of China. It could be said that, compared to the political uprising of May Fourth, this other related trend, the “New Culture Movement”, as it was later called, was not only developing longer than its political counterpart, but also had much longer lasting implications. The protagonists of the New Culture Movement pinpointed traditional Chinese culture as the cause of China’s failure, and blamed it for the limits it imposed upon the Chinese society and nation. -

(1893-1976) Mao Zedong Led China's Communist Revolution in The

Mao Zedong 1 (1893-1976) Mao Zedong led China's Communist revolution in the 1920s and 1930s and became chairman (chief of state) of the People's Republic of China in 1949, an office he held until 1959. From "Mao Zedong." Microsoft Encarta Encyclopedia 2001. Mao Zedong was the foremost Chinese Communist leader of the 20th century and the principal founder of the People's Republic of China. Mao was born December 26, 1893, into a peasant family in the village of Shaoshan, Hunan province. His father was a strict disciplinarian and Mao frequently rebelled against his authority. Mao's early education was in the Confucian classics of Chinese history, literature, and philosophy, but early teachers also exposed him to the ideas of progressive Confucian reformers such as K'ang Yu-wei. In 1911 Mao moved to the provincial capital, Changsha, where he briefly served as a soldier in Republican army in the 1911 revolution that overthrew the Qing dynasty. While in Changsha, Mao read works on Western philosophy; he was also greatly influenced by progressive newspapers and by journals such as New Youth, founded by revolutionary leader Chen Duxiu. In 1918, after graduating from the Hunan Teachers College in Changsha, Mao traveled to Beijing and obtained a job in the Beijing University library under the head librarian, Li Dazhao. Mao joined Li's study group that explored Marxist political and social thought and he became an avid reader of Marxist writings. During the May Fourth Movement of 1919, when students and intellectuals called for China's modernization, Mao published articles criticizing the traditional values of Confucianism. -

BOOK REVIEWS Chen Yao-Huang 陳耀煌, Tonghe Yu Fenhua

Front. Hist. China 2013, 8(4): 621–640 BOOK REVIEWS Chen Yao-huang 陳耀煌, Tonghe yu fenhua: Hebei diqu de gongchan geming: 1921–1949 統合與分化:河北地區的共產革命:1921–1949 (Integrate and Divide: The Communist Revolution in Hebei Area, 1921–1949). Taibei: Institute of Modern History, Academia Sinica, 2012. ISBN 9789860333459. X+510pp. NT$ 450.00. DOI 10.3868/s020-002-013-0042-0 For decades, the victory of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has been fascinating historians of modern China who work outside of the People’s Republic of China. After recognizing the complexity of the Chinese Revolution, they have tended to focus on specific regions, applying the approaches of a variety of disciplines including sociology, a trend that gave rise to the field of “base area studies,” marked by the publishing of Mark Sheldon’s The Yenan Way in 1971. This new book by Chen Yao-huang is another remarkable contribution to the study of base areas. With it, he has filled the gap in knowledge about the CCP’s origins and its growth in Hebei province, a strategically important gateway between the CCP base areas in mountainous Shanxi and the productive provinces in east and northeast China. Chen argues that the economy and society of Hebei before the Sino-Japanese War that began in 1937 were agrarian and fragmented. The leadership of Li Dazhao, one of the CCP’s founding fathers and the head of the Hebei CCP until his death in 1927, was similar to that of the head of a Confucian patriarchic clan in an area without conditions for a Communist revolution.