Plug-In Electric Vehicles: a Practical Plan for Progress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016 Buick Lacrosse Owner Manual

2k16_CS6_Buick_Lacrosse_23180150C.ai 1 2/9/2016 9:49:19 AM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K 23180150 C Buick LaCrosse Owner Manual (GMNA-Localizing-U.S./Canada/Mexico- 9159288) - 2016 - CRC - 10/5/15 Contents Introduction . 2 In Brief . 5 Keys, Doors, and Windows . 26 Seats and Restraints . 49 Storage . 97 Instruments and Controls . 100 Lighting . 148 Infotainment System . 156 Climate Controls . 157 Driving and Operating . 163 Vehicle Care . 226 Service and Maintenance . 313 Technical Data . 326 Customer Information . 330 Reporting Safety Defects . 341 OnStar . 345 Index . 355 Buick LaCrosse Owner Manual (GMNA-Localizing-U.S./Canada/Mexico- 9159288) - 2016 - CRC - 2/3/16 2 Introduction Introduction This manual describes features that Helm, Incorporated may or may not be on the vehicle Attention: Customer Service because of optional equipment that 47911 Halyard Drive was not purchased on the vehicle, Plymouth, MI 48170 model variants, country USA specifications, features/applications that may not be available in your Using this Manual region, or changes subsequent to the printing of this owner manual. To quickly locate information about the vehicle, use the Index in the The names, logos, emblems, Refer to the purchase back of the manual. It is an slogans, vehicle model names, and documentation relating to your alphabetical list of what is in the vehicle body designs appearing in specific vehicle to confirm the manual and the page number where this manual including, but not limited features. it can be found. to, GM, the GM logo, BUICK, the BUICK Emblem, and LACROSSE Keep this manual in the vehicle for are trademarks and/or service quick reference. -

Design of an Efficient, Low Weight Battery Electric Vehicle Based on a VW Lupo 3L

© EVS-25 Shenzhen, China, Nov. 5-9, 2010 The 25th World Battery, Hybrid and Fuel Cell Electric Vehicle Symposium & Exhibition Design of an efficient, low weight battery electric vehicle based on a VW Lupo 3L I.J.M. Besselink1, P.F. van Oorschot1, E. Meinders1, and H. Nijmeijer1 1Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, Eindhoven University of Technology, P.O. Box 513, 5600 MB Eindhoven, The Netherlands E-mail: [email protected] Abstract—A battery electric vehicle is being developed at the Eindhoven University of Technology, which will be used in future research projects regarding electric mobility. Energy storage in batteries is still at least 25 times heavier and has 10 times the volume in comparison to fossil fuel. This leads to an increase of the vehicle weight, especially when trying to maximise the range. A set of specifications is derived, taking into consideration the mobility requirements of people living in the Netherlands and the capabilities of electric vehicles. The VW Lupo 3L 1.2 TDI has been selected as the vehicle to be converted into a battery electric vehicle, since it has many favourable characteristics such as a very low mass and good aerodynamics. The design choices considering the power train and component selection are discussed in detail. Finally the battery electric Lupo is compared to the original Lupo 3L considering energy usage, costs per km and CO2 emissions. With respect to these aspects the advantages of electric propulsion are relatively small, as the donor vehicle is already very fuel efficient. Copyright Form of EVS25. Keywords—battery electric vehicle, power train, vehicle performance project is to develop and demonstrate environmentally 1. -

One Million Electric Vehicles by 2015

One Million Electric Vehicles By 2015 February 2011 Status Report 1 Executive Summary President Obama’s goal of putting one million electric vehicles on the road by 2015 represents a key milestone toward dramatically reducing dependence on oil and ensuring that America leads in the growing electric vehicle manufacturing industry. Although the goal is ambitious, key steps already taken and further steps proposed indicate the goal is achievable. Indeed, leading vehicle manufacturers already have plans for cumulative U.S. production capacity of more than 1.2 million electric vehicles by 2015, according to public announcements and news reports. While it appears that the goal is within reach in terms of production capacity, initial costs and lack of familiarity with the technology could be barriers. For that reason, President Obama has proposed steps to accelerate America’s leadership in electric vehicle deployment, including improvements to existing consumer tax credits, programs to help cities prepare for growing demand for electric vehicles and strong support for research and development. Introduction In his 2011 State of the Union address, President Obama called for putting one million electric vehicles on the road by 2015 – affirming and highlighting a goal aimed at building U.S. leadership in technologies that reduce our dependence on oil.1 Electric vehicles (“EVs”) – a term that includes plug-in hybrids, extended range electric vehicles and all- electric vehicles -- represent a key pathway for reducing petroleum dependence, enhancing environmental stewardship and promoting transportation sustainability, while creating high quality jobs and economic growth. To achieve these benefits and reach the goal, President Obama has proposed a new effort that supports advanced technology vehicle adoption through improvements to tax credits in current law, investments in R&D and competitive “With more research and incentives, programs to encourage communities to invest we can break our dependence on oil in infrastructure supporting these vehicles. -

Comparative Review of a Dozen National Energy Plans: Focus on Renewable and Efficient Energy

Technical Report A Comparative Review of a Dozen NREL/TP-6A2-45046 National Energy Plans: Focus on March 2009 Renewable and Efficient Energy Jeffrey Logan and Ted L. James Technical Report A Comparative Review of a Dozen NREL/TP-6A2-45046 National Energy Plans: Focus on March 2009 Renewable and Efficient Energy Jeffrey Logan and Ted L. James Prepared under Task No. SAO7.9C50 National Renewable Energy Laboratory 1617 Cole Boulevard, Golden, Colorado 80401-3393 303-275-3000 • www.nrel.gov NREL is a national laboratory of the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Operated by the Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC Contract No. DE-AC36-08-GO28308 NOTICE This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States government. Neither the United States government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States government or any agency thereof. Available electronically at http://www.osti.gov/bridge Available for a processing fee to U.S. -

Bringing the Auto Industry, U.S. Government and Car Consumers

WANADA Bulletin # 4-10 *** 2010 Washington Auto Show Special Issue February 1, 2010 Headlines… 2010 WAS: The Future of the Automobile in Society The Washington Auto Show “is important to Ford because of the constituents here,” says CEO Mulally EPA Administrator Opens Advanced Technology SuperHighway Energy Secretary Chu Announces $1.4 Billion Loan to Nissan Read The Green Car Summit on Capitol Hill Congress Joins WAS Public Policy Day The Daily Bulletin coverage “Sneak Peek” Reception and Preview Draws a “Capitol” Crowd of the Auto Show, Jan. 25-29 WANADA Member Briefing, Chrysler, GM & the Industry Turmoil Student Day at the Auto Show: An Educational Experience here 06/08/2009 Ralph Nader Recognized by Keith Crain/Automotive News EDTA and SAE International Hold Joint Plenary Session at The 2010 Washington Auto Show Thought for the Week… The 2010 Washington Auto Show: Bringing the Auto Industry, U.S. Government and Car Consumers Together on the Future of the Automobile in Society The 2010 Washington Auto Show (WAS) and its organizers achieved what they set out to do on Public Policy Days, Jan 25-26, in bring ing together the key public and private sector players who will decide how the auto industry will evolve in the years ahead. They also successfully assembled a show floor exposition that vividly displayed its direction, particularly within the Advanced Technology SuperHighway, the show’s signature pavilion. Those attending Public Policy Days included leading industry executives, federal officials, congressmen, local elected representatives and affiliated auto industry associations. Together they produced one of the most meaningful public policy forums in the show’s history. -

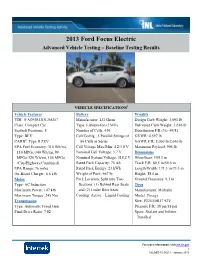

2013 Ford Focus Electric Advanced Vehicle Testing – Baseline Testing Results

2013 Ford Focus Electric Advanced Vehicle Testing – Baseline Testing Results VEHICLE SPECIFICATIONS1 Vehicle Features Battery Weights VIN: 1FADP3R42DL268207 Manufacturer: LG Chem Design Curb Weight: 3,691 lb Class: Compact Car Type: Lithium-Ion (LMO) Delivered Curb Weight: 3,616 lb Seatbelt Positions: 5 Number of Cells: 430 Distribution F/R (%): 49/51 Type: BEV Cell Config.: 5 Parallel Strings of GVWR: 4,597 lb CARB2: Type II ZEV 86 Cells in Series GAWR F/R: 2,060 lb/2,646 lb EPA Fuel Economy: 310 Wh/mi, Cell Voltage Max/Min: 4.2/3.0 V Maximum Payload: 906 lb 110 MPGe/340 Wh/mi, 99 Nominal Cell Voltage: 3.7 V Dimensions MPGe/320 Wh/mi, 105 MPGe Nominal System Voltage: 318.2 V Wheelbase: 104.3 in (City/Highway/Combined) Rated Pack Capacity: 75 Ah Track F/R: 60.5 in/59.6 in EPA Range: 76 miles Rated Pack Energy: 23 kWh Length/Width: 171.3 in/73.3 in On-Board Charger: 6.6 kW Weight of Pack: 667 lb Height: 58.6 in Motor Pack Location: Split into Two Ground Clearance: 6.3 in Type: AC Induction Sections: (1) Behind Rear Seats Tires Maximum Power: 107 kW and (2) Under Rear Seats Manufacturer: Michelin Maximum Torque: 245 Nm Cooling: Active – Liquid Cooling Model: Energy Transmission Size: P225/50R17 93V Type: Automatic Fixed Gear Pressure F/R: 38 psi/38 psi Final Drive Ratio: 7.82 Spare: Sealant and Inflator Installed For more information, visit avt.inl.gov 1 INL/MIS-15-34211 • January 2015 PERFORMANCE STATISTICS3 TRACK TESTING4 DYNAMOMETER TESTING9 Acceleration 0-60 mph5 Cycle Results10 Measured Time: 10.9 s 72 °F 20 °F 95 °F + 850 W/m2 UDDS -

Bear Facts Tom [email protected]

Badger Consultants, LLC The Report Date: Thomas S. Chanos April 25, 2006 (608) 274-5019 Bear Facts [email protected] Energy Conversion Devices Inc. ENER - $53.00 – NasdaqNM New Recommendation Recommendation: Sell Short Reasons For Short Sale Recommendation Alternative Energy Plays-Solar, computer memory and hybrid auto batteries. ‹ Stock up almost 150% in less than one year. ‹ Currently unprofitable. ‹ P/E of 883 times 2007 EPS of $0.06, which we highly doubt. ‹ ENER was supposed to be profitable in 2006 (June). Not any more. ‹ Negative Cash Flow. ‹ Stock price up on competitors supply shortages. ‹ Exclusive distribution agreement with Solar Integrated Technologies (SIT.LN), which is in precarious financial condition. ‹ Range of applications for technology is not as good as traditional Solar (polysilicon) technology. ‹ Popular in Germany and States that offer tax credits, but winding down. ‹ Lots of licensing deals and joint venture “announcements”. ‹ Retail investor hype. Financials 52 – Week Low 6-8-2005 $16.07 Book Value/Shr (mrq) $5.30 52 – Week high 1-24-2006 $57.84 Diluted Earnings/Shr (ttm) -$1.03 Daily Volume Avg. 1,673,440 Diluted Earnings/Shr mrq) -$0.21 52 – Week Change +148% Sales/Shr (ttm) $2.93 Market Capitalization $1.63B Cash/Shr (mrq) $2.23 Shares Outstanding 30.88M Price/Book (mrq) 10.0 Float 30.04M Price/Earnings (ttm) NA Profit Margin (mrq) -35.20% Price/Sales (ttm) 18.46 Operating Margin (ttm) -37.65% Revenue (ttm) $86.24M Return on Assets (ttm) -12.55% EBITDA (ttm) -$24.70M Return on Equity (ttm) -25.31% Debt/Equity (mrq) 0 Operating Cash Flow (ttm) -$34.43M Shares Short 4-8-05 NA Leveraged Free Cash Flow (ttm) -$53.09 % of Float Short NA Total Cash (mrq) $68.93M Short Ratio NA (ttm) = Trailing 12 months, (mrq) = Most recent quarter, M = Millions, B = Billions, m = Thousands - Page 1 - All information contained herein is obtained by Badger Consultants, LLC from sources believed by it to be accurate and reliable. -

Easy Battery Swapping

EasyEasy BatteryBattery SwappingSwapping Gilles MULATO Chanan GABAY Jacques POILLOT Amit YUDAN Gonzalo HENNEQUET BetterBetter PlacePlace RENAULTRENAULT G. Hennequet June 30, 2011 CONTENTS: 1. RENAULT & Better Place Battery Swapping History 2. Current Renault Fluence Z.E. Quick Drop System 3. Current Better Place Quick Drop Stations 4. The Future: The EASYBAT Project G. Hennequet June 30, 2011 2 1. Renault & Better Place Battery Bay History Battery Swapping : State of the Art By switching the battery of the electric vehicle, its range can be extended. A switchable battery pack is a battery pack that can be easily installed and removed into and out of the electric vehicle. The battery bay is a set of interfaces between an electric vehicle (EV) and a switchable battery pack. Two battery bay alternatives exist today: 1st Commercial Generation of the Fluence Z.E. (Renault). Better Place alternative Battery Bay concept G. Hennequet June 30, 2011 3 1. Renault & Better Place Battery Bay History March 2008: • Renault reveals its 1st Generation Battery Bay design for Fluence. July 2008: • Better Place presents conceptual design for battery switch station. May 2009: • Better Place demonstrates alternative Battery Bay concept in Japan. September 2009: • Renault demonstrates the Fluence including the commercial 1st Generation in Frankfurt auto show. April 2010: • Better Place demonstrates its alternative Battery Bay prototype on electric taxis in Tokyo, Japan. July 2010: • Better Place demonstrates integration of Fluence 1st Generation in the BP Alpha battery switch station G. Hennequet June 30, 2011 4 2. Current Renault Fluence Z.E. Quick Drop System WHY A BATTERY QUICK EXCHANGE SYSTEM? => QUICK DROP G. -

Global Mobility Through Changing Times Sustainability Report 2014/15

Sustainability Report 2014/15 c d b ] e a Home Year in Strategy and MOBILITY PRODUCT QUALITY CLIMATE CHANGE AND OUR PEOPLE SUPPLY CHAIN COMMUNITIES Review Governance AND SAFETY ENVIRONMENT Global Mobility Through Changing Times Sustainability Report 2014/15 We want to change how the world moves. Again. “At Ford, mobility is about far more than motion. It is really about progress. Human progress.” – Mark Fields, President and Chief Executive Officer ? Spotlight Stories We challenged software developers to help The new F-150 is Ford’s toughest, most capable accident victims during the “golden hour” in – and most sustainable – truck ever. India. Ford provides tools, technology and training to We’re developing a globally mobile workforce Can electric bikes link multi-modal travel for help drivers perform their best. to deliver innovation. commuters? We’re experimenting to find out. @ Two-Minute Summary We are driving to be both a product company and a mobility company. Our vision is nothing less than to change the way the world moves. At Ford, we view this as the ultimate opportunity. In fact it is as big of an opportunity as when our founder put the world on wheels more than a century ago. Take a quick look at what we’ve achieved this year... Innovating Mobility Solutions In early 2015, we announced Ford Smart Mobility, which is using innovation to take Ford to the next level in connectivity, mobility, autonomous vehicles, big data and the customer experience. We view the disruption that’s taking place in mobility as something to embrace – not fear. -

Electric Drive by '25

ELECTRIC DRIVE BY ‘25: How California Can Catalyze Mass Adoption of Electric Vehicles by 2025 September 2012 About this Report This policy paper is the tenth in a series of reports on how climate change will create opportunities for specific sectors of the business community and how policy-makers can facilitate those opportunities. Each paper results from one-day workshop discussions that include representatives from key business, academic, and policy sectors of the targeted industries. The workshops and resulting policy papers are sponsored by Bank of America and produced by a partnership of the UCLA School of Law’s Environmental Law Center & Emmett Center on Climate Change and the Environment and UC Berkeley School of Law’s Center for Law, Energy & the Environment. Authorship The author of this policy paper is Ethan N. Elkind, Bank of America Climate Policy Associate for UCLA School of Law’s Environmental Law Center & Emmett Center on Climate Change and the Environment and UC Berkeley School of Law’s Center for Law, Energy & the Environment (CLEE). Additional contributions to the report were made by Sean Hecht and Cara Horowitz of the UCLA School of Law and Steven Weissman of the UC Berkeley School of Law. Acknowledgments The author and organizers are grateful to Bank of America for its generous sponsorship of the workshop series and input into the formulation of both the workshops and the policy paper. We would specifically like to thank Anne Finucane, Global Chief Strategy and Marketing Officer, and Chair of the Bank of America Environmental Council, for her commitment to this work. -

Page 1 of 32 VEHICLE RECALLS by MANUFACTURER, 2000 Report Prepared 1/16/2008

Page 1 of 32 VEHICLE RECALLS BY MANUFACTURER, 2000 Report Prepared 1/16/2008 MANUFACTURER RECALLS VEHICLES ACCUBUIL T, INC 1 8 AM GENERAL CORPORATION 1 980 AMERICAN EAGLE MOTORCYCLE CO 1 14 AMERICAN HONDA MOTOR CO 8 212,212 AMERICAN SUNDIRO MOTORCYCLE 1 2,183 AMERICAN SUZUKI MOTOR CORP. 4 25,023 AMERICAN TRANSPORTATION CORP. 5 1,441 APRILIA USA INC. 2 409 ASTON MARTIN 2 666 ATHEY PRODUCTS CORP. 3 304 B. FOSTER & COMPANY, INC. 1 422 BAYERISCHE MOTOREN WERKE 11 28,738 BLUE BIRD BODY COMPANY 12 62,692 BUELL MOTORCYCLE CO 4 12,230 CABOT COACH BUILDERS, INC. 1 818 CARPENTER INDUSTRIES, INC. 2 6,838 CLASSIC LIMOUSINE 1 492 CLASSIC MANUFACTURING, INC. 1 8 COACHMEN INDUSTRIES, INC. 8 5,271 COACHMEN RV COMPANY 1 576 COLLINS BUS CORPORATION 1 286 COUNTRY COACH INC 6 519 CRANE CARRIER COMPANY 1 138 DABRYAN COACH BUILDERS 1 723 DAIMLERCHRYSLER CORPORATION 30 6,700,752 DAMON CORPORATION 3 824 DAVINCI COACHWORKS, INC 1 144 D'ELEGANT CONVERSIONS, INC. 1 34 DORSEY TRAILERS, INC. 1 210 DUTCHMEN MANUFACTURING, INC 1 105 ELDORADO NATIONAL 1 173 ELECTRIC TRANSIT, INC. 1 54 ELGIN SWEEPER COMPANY 1 40 E-ONE, INC. 1 3 EUROPA INTERNATIONAL, INC. 2 242 EXECUTIVE COACH BUILDERS 1 702 FEATHERLITE LUXURY COACHES 1 83 FEATHERLITE, INC. 2 3,235 FEDERAL COACH, LLC 1 230 FERRARI NORTH AMERICA 8 1,601 FLEETWOOD ENT., INC. 5 12, 119 FORD MOTOR COMPANY 60 7,485,466 FOREST RIVER, INC. 1 115 FORETRAVEL, INC. 3 478 FOURWINNS 2 2,276 FREIGHTLINER CORPORATION 27 233,032 FREIGHTLINER LLC 1 803 GENERAL MOTORS CORP. -

Research and Development of Electric Vehicle in China and Latest Trends on Diffusion

Research and Development of Electric Vehicle in China and Latest Trends on Diffusion China Automotive Technology & Research Center (CATARC) Ma JianYong [email protected] 1. Research and manufacture of EV in China 2 2 2012,15495 thousand passenger cars were sold in china. Chinese government will attempt to double citizens' revenue before 2020. And this plan will promote the passenger cars market continue increase. 中国乘用车市场发展 变化趋势 18000000 60% 销量 同比 Sales Growth rate 15493669 16000000 52.9% 50.0% 14472416 50% 13757794 14000000 45.7% 12000000 40% 10331315 10000000 33.2% 30.8% 29.6% 30% 8000000 6755609 6297533 22.3% 6000000 5148546 20% 16.0%3973624 4000000 3036842 2618922 10% 1745585 2000000 1197996 7.3% 5.2% 0 0% 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012E 3 3 Support Policies from Central Government “Carry out energy- saving and new "Automobile industry “New energy "Notice on the private energy vehicle restructuring and vehicle production purchase of new demonstration pilot revitalization plan" companies and energy vehicles work notice” product access subsidy pilot” rules " 2001.1 2009.1.23 2009.2 2009.3 2009.5 2009.7 2009.12 2010.6 2012.7 "Energy-saving and Interim new energy Measures for the 10 billion CNY of automotive industry Administration of funds of the State development plan 863major projects energy-saving Council to support (2010-2120)" of Electric vehicle and new energy technical R&D and financial innovation New energy vehicle industrialization assistance demonstration pilot cities to extend 4 Bulletin number