Choreographing Genre in Kill Bill Vol. 1 & 2 (Quentin Tarantino, 2003

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pulp Fiction © Jami Bernard the a List: the National Society of Film Critics’ 100 Essential Films, 2002

Pulp Fiction © Jami Bernard The A List: The National Society of Film Critics’ 100 Essential Films, 2002 When Quentin Tarantino traveled for the first time to Amsterdam and Paris, flush with the critical success of “Reservoir Dogs” and still piecing together the quilt of “Pulp Fiction,” he was tickled by the absence of any Quarter Pounders with Cheese on the European culinary scene, a casualty of the metric system. It was just the kind of thing that comes up among friends who are stoned or killing Harvey Keitel (left) and Quentin Tarantino attempt to resolve “The Bonnie Situation.” time. Later, when every nook and cranny Courtesy Library of Congress of “Pulp Fiction” had become quoted and quantified, this minor burger observation entered pop (something a new generation certainly related to through culture with a flourish as part of what fans call the video games, which are similarly structured). Travolta “Tarantinoverse.” gets to stare down Willis (whom he dismisses as “Punchy”), something that could only happen in a movie With its interlocking story structure, looping time frame, directed by an ardent fan of “Welcome Back Kotter.” In and electric jolts, “Pulp Fiction” uses the grammar of film each grouping, the alpha male is soon determined, and to explore the amusement park of the Tarantinoverse, a the scene involves appeasing him. (In the segment called stylized merging of the mundane with the unthinkable, “The Bonnie Situation,” for example, even the big crime all set in a 1970s time warp. Tarantino is the first of a boss is so inexplicably afraid of upsetting Bonnie, a night slacker generation to be idolized and deconstructed as nurse, that he sends in his top guy, played by Harvey Kei- much for his attitude, quirks, and knowledge of pop- tel, to keep from getting on her bad side.) culture arcana as for his output, which as of this writing has been Jack-Rabbit slim. -

H K a N D C U L T F I L M N E W S

More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In H K A N D C U L T F I L M N E W S H K A N D C U LT F I L M N E W S ' S FA N B O X W E L C O M E ! HK and Cult Film News on Facebook I just wanted to welcome all of you to Hong Kong and Cult Film News. If you have any questions or comments M O N D AY, D E C E M B E R 4 , 2 0 1 7 feel free to email us at "SURGE OF POWER: REVENGE OF THE [email protected] SEQUEL" Brings Cinema's First Out Gay Superhero Back to Theaters in January B L O G A R C H I V E ▼ 2017 (471) ▼ December (34) "MORTAL ENGINES" New Peter Jackson Sci-Fi Epic -- ... AND NOW THE SCREAMING STARTS -- Blu-ray Review by ... ASYLUM -- Blu-ray Review by Porfle She Demons Dance to "I Eat Cannibals" (Toto Coelo)... Presenting -- The JOHN WAYNE/ "GREEN BERETS" Lunch... Gravitas Ventures "THE BILL MURRAY EXPERIENCE"-- i... NUTCRACKER, THE MOTION PICTURE -- DVD Review by Po... John Wayne: The Crooning Cowpoke "EXTRAORDINARY MISSION" From the Writer of "The De... "MOLLY'S GAME" True High- Stakes Poker Thriller In ... Surge of Power: Revenge of the Sequel Hits Theaters "SHOCK WAVE" With Andy Lau Cinema's First Out Gay Superhero Faces His Greatest -- China’s #1 Box Offic... Challenge Hollywood Legends Face Off in a New Star-Packed Adventure Modern Vehicle Blooper in Nationwide Rollout Begins in January 2018 "SHANE" (1953) "ANNIHILATION" Sci-Fi "A must-see for fans of the TV Avengers, the Fantastic Four Thriller With Natalie and the Hulk" -- Buzzfeed Portma.. -

Masaaki Hatsumi and Togakure Ryu

How Ninja Conquered the World THE TIMELINE OF SHINOBI POP CULTURE’S WORLDWIDE EXPLOSION Version 1.3 ©Keith J. Rainville, 2020 How did insular Japan’s homegrown hooded set go from local legend to the most marketable character archetype in the world by the mid-1980s? VN connects the dots below, but before diving in, please keep a few things in mind: • This timeline is a ‘warts and all’ look at a massive pop-culture phenomenon — meaning there are good movies and bad, legit masters and total frauds, excellence and exploitation. It ALL has to be recognized to get a complete picture of why the craze caught fire and how it engineered its own glass ceiling. Nothing is being ranked, no one is being endorsed, no one is being attacked. • This is NOT TO SCALE, the space between months and years isn’t literal, it’s a more anecdotal portrait of an evolving phenomenon. • It’s USA-centric, as that’s where VN originates and where I lived the craze myself. And what happened here informed the similar eruptions all over Europe, Latin America etc. Also, this isn’t a history of the Japanese booms that predated ours, that’s someone else’s epic to outline. • Much of what you see spotlighted here has been covered in more depth on VintageNinja.net over the past decade, so check it out... • IF I MISSED SOMETHING, TELL ME! I’ll be updating the timeline from time to time, so if you have a gap to fill or correction to offer drop me a line! Pinholes of the 1960s In Japan, from the 1600s to the 1960s, a series of booms and crazes brought the ninja from shadowy history to popular media. -

Ludacris – Red Light District Brothers in Arms the Pacifier

Pickwick's Video/DVD Rentals – New Arrivals 19. Sept. 2005 Marc Aurel Str. 10-12, 1010 Vienna Tel. 01-533 0182 – open daily – http://www.pickwicks.at/ __________________________________________________________________ Ludacris – Red Light District Genre: Music Synopsis: Live concert from Amsterdam plus three music videos. Brothers In Arms Genre: Action Actors: David Carradine, Kenya Moore, Gabriel Casseus, Antwon Tanner, Raymond Cruz Director: Jean-Claude La Marre Synopsis: A crew of outlaws set out to rob the town boss who murdered one of their kinsmen. Driscoll is warned so his thugs surround the outlaws and soon there is a shootout. Set in the American West. The Pacifier Genre: Comedy Actors: Vin Diesel, Lauren Graham, Faith Ford, Brittany Snow, Max Theriot, Carol Kane, Brad Gardett Director: Adam Shankman Synopsis: The story of an undercover agent who, after failing to protect an important government scientist, learns the man's family is in danger. In an effort to redeem himself, he agrees to take care of the man's children only to discover that child care is his toughest mission yet. Pickwick's Video/DVD Rentals – New Arrivals 19. Sept. 2005 Marc Aurel Str. 10-12, 1010 Vienna Tel. 01-533 0182 – open daily – http://www.pickwicks.at/ __________________________________________________________________ The Killer Language: Japanese Genre: Action Actors: Chow Yun Fat Director: John Woo Synopsis: The story of an assassin, Jeffrey Chow (aka Mickey Mouse) who takes one last job so he can retire and care for his girlfriend Jenny. When his employers betray him, he reluctantly joins forces with Inspector Lee (aka Dumbo), the cop who is pursuing him. -

Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5pg3z8fg Author Chien, Irene Y. Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames by Irene Yi-Jiun Chien A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media and the Designated Emphasis in New Media in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Linda Williams, Chair Professor Kristen Whissel Professor Greg Niemeyer Professor Abigail De Kosnik Spring 2015 Abstract Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames by Irene Yi-Jiun Chien Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media Designated Emphasis in New Media University of California, Berkeley Professor Linda Williams, Chair Programmed Moves examines the intertwined history and transnational circulation of two major videogame genres, martial arts fighting games and rhythm dancing games. Fighting and dancing games both emerge from Asia, and they both foreground the body. They strip down bodily movement into elemental actions like stepping, kicking, leaping, and tapping, and make these the form and content of the game. I argue that fighting and dancing games point to a key dynamic in videogame play: the programming of the body into the algorithmic logic of the game, a logic that increasingly organizes the informatic structure of everyday work and leisure in a globally interconnected information economy. -

ANÁLISIS DE FUCK Y SU TRADUCCIÓN AL ESPAÑOL EN JACKIE BROWN Betlem Soler Pardo Universitat De València

ENTRECULTURAS Número 6. ISSN: 1989-5097. Fecha de publicación: 29-01-2014 TRADUCCIÓN Y DOBLAJE: ANÁLISIS DE FUCK Y SU TRADUCCIÓN AL ESPAÑOL EN JACKIE BROWN Betlem Soler Pardo Universitat de València ABSTRACT Four-letter words are the most obscene and vulgar words in the English language; these refer to parts of the body, bodily functions, human waste, and sex, to cite a few examples. Of all these categories, the one which involves sex is the most obscene of all, and among this group, the most vulgar is fuck (Montagu, 1967; Allan and Burridge, 2006). This paper aims, firstly, to examine a paradigmatic sample of the f-word as it appears in Jackie Brown, a neo noir film directed by Quentin Tarantino; secondly, to carry out research on the categorization of fuck based on the work of McEnery and Xiao (2004); thirdly, to analyse the translation for dubbing of this controversial word into Spanish; and finally, to establish if the presence of fuck in the Spanish version of Jackie Brown has decreased or increased after having carried out the transfer of words. KEYWORDS: audiovisual translation, dubbing, swearwords, the f-word, Jackie Brown, Quentin Tarantino RESUMEN Las llamadas palabras de cuatro letras son consideradas las más obscenas y vulgares de la lengua inglesa, ya que hacen referencia a las partes del cuerpo, a las funciones fisiológicas, al producto de éstas, y al sexo, entre otras. De todas estas categorías, la concerniente al sexo es considerada la más obscena y, entre este grupo, la palabra más vulgar es fuck(Montagu, 1967; Allan and Burridge, 2006). -

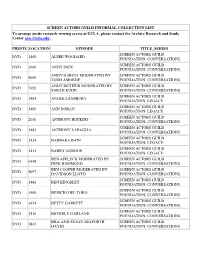

SCREEN ACTORS GUILD INFORMAL COLLECTION LIST to Arrange Onsite Research Viewing Access at UCLA, Please Contact the Archive Research and Study Center [email protected]

SCREEN ACTORS GUILD INFORMAL COLLECTION LIST To arrange onsite research viewing access at UCLA, please contact the Archive Research and Study Center [email protected] . PREFIX LOCATION EPISODE TITLE_SERIES SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1460 ALFRE WOODARD FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1669 ANDY DICK FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS ANDY GARCIA MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 8699 TODD AMORDE FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS ANDY RICHTER MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 7020 SARAH KUHN FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1484 ANGLE LANSBURY FOUNDATION: LEGACY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1409 ANN DORAN FOUNDATION: LEGACY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 2010 ANTHONY HOPKINS FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1483 ANTHONY LAPAGLIA FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1434 BARBARA BAIN FOUNDATION: LEGACY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1413 BARRY GORDON FOUNDATION: LEGACY BEN AFFLECK MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 6348 PETE HAMMOND FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS BEN COOPER MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 8697 DAVIDSON LLOYD FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1486 BEN KINGSLEY FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1500 BENICIO DEL TORO FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1674 BETTY GARRETT FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1416 BEVERLY GARLAND FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS BILL AND SUSAN SEAFORTH SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1843 HAYES FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS BILL PAXTON MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 7019 JENELLE RILEY FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS -

Download Heroic Grace: the Chinese Martial Arts Film Catalog (PDF)

UCLA Film and Television Archive Hong Kong Economic and Trade Office in San Francisco HEROIC GRACE: THE CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS FILM February 28 - March 16, 2003 Los Angeles Front and inside cover: Lau Kar-fai (Gordon Liu Jiahui) in THE 36TH CHAMBER OF SHAOLIN (SHAOLIN SANSHILIU FANG ) present HEROIC GRACE: THE CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS FILM February 28 - March 16, 2003 Los Angeles Heroic Grace: The Chinese Martial Arts Film catalog (2003) is a publication of the UCLA Film and Television Archive, Los Angeles, USA. Editors: David Chute (Essay Section) Cheng-Sim Lim (Film Notes & Other Sections) Designer: Anne Coates Printed in Los Angeles by Foundation Press ii CONTENTS From the Presenter Tim Kittleson iv From the Presenting Sponsor Annie Tang v From the Chairman John Woo vi Acknowledgments vii Leaping into the Jiang Hu Cheng-Sim Lim 1 A Note on the Romanization of Chinese 3 ESSAYS Introduction David Chute 5 How to Watch a Martial Arts Movie David Bordwell 9 From Page to Screen: A Brief History of Wuxia Fiction Sam Ho 13 The Book, the Goddess and the Hero: Sexual Bérénice Reynaud 18 Aesthetics in the Chinese Martial Arts Film Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon—Passing Fad Stephen Teo 23 or Global Phenomenon? Selected Bibliography 27 FILM NOTES 31-49 PROGRAM INFORMATION Screening Schedule 51 Print & Tape Sources 52 UCLA Staff 53 iii FROM THE PRESENTER Heroic Grace: The Chinese Martial Arts Film ranks among the most ambitious programs mounted by the UCLA Film and Television Archive, taking five years to organize by our dedicated and intrepid Public Programming staff. -

MADE in HOLLYWOOD, CENSORED by BEIJING the U.S

MADE IN HOLLYWOOD, CENSORED BY BEIJING The U.S. Film Industry and Chinese Government Influence Made in Hollywood, Censored by Beijing: The U.S. Film Industry and Chinese Government Influence 1 MADE IN HOLLYWOOD, CENSORED BY BEIJING The U.S. Film Industry and Chinese Government Influence TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY I. INTRODUCTION 1 REPORT METHODOLOGY 5 PART I: HOW (AND WHY) BEIJING IS 6 ABLE TO INFLUENCE HOLLYWOOD PART II: THE WAY THIS INFLUENCE PLAYS OUT 20 PART III: ENTERING THE CHINESE MARKET 33 PART IV: LOOKING TOWARD SOLUTIONS 43 RECOMMENDATIONS 47 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 53 ENDNOTES 54 Made in Hollywood, Censored by Beijing: The U.S. Film Industry and Chinese Government Influence MADE IN HOLLYWOOD, CENSORED BY BEIJING EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ade in Hollywood, Censored by Beijing system is inconsistent with international norms of Mdescribes the ways in which the Chinese artistic freedom. government and its ruling Chinese Communist There are countless stories to be told about China, Party successfully influence Hollywood films, and those that are non-controversial from Beijing’s warns how this type of influence has increasingly perspective are no less valid. But there are also become normalized in Hollywood, and explains stories to be told about the ongoing crimes against the implications of this influence on freedom of humanity in Xinjiang, the ongoing struggle of Tibetans expression and on the types of stories that global to maintain their language and culture in the face of audiences are exposed to on the big screen. both societal changes and government policy, the Hollywood is one of the world’s most significant prodemocracy movement in Hong Kong, and honest, storytelling centers, a cinematic powerhouse whose everyday stories about how government policies movies are watched by millions across the globe. -

Martial Arts Cinema and Hong Kong Modernity

Martial Arts Cinema and Hong Kong Modernity Aesthetics, Representation, Circulation Man-Fung Yip Hong Kong University Press Th e University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © 2017 Hong Kong University Press ISBN 978-988-8390-71-7 (Hardback) All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any infor- mation storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. An earlier version of Chapter 2 “In the Realm of the Senses” was published as “In the Realm of the Senses: Sensory Realism, Speed, and Hong Kong Martial Arts Cinema,” Cinema Journal 53 (4): 76–97. Copyright © 2014 by the University of Texas Press. All rights reserved. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Paramount Printing Co., Ltd. in Hong Kong, China Contents Acknowledgments viii Notes on Transliteration x Introduction: Martial Arts Cinema and Hong Kong Modernity 1 1. Body Semiotics 24 2. In the Realm of the Senses 56 3. Myth and Masculinity 85 4. Th e Diffi culty of Diff erence 115 5. Marginal Cinema, Minor Transnationalism 145 Epilogue 186 Filmography 197 Bibliography 203 Index 215 Introduction Martial Arts Cinema and Hong Kong Modernity Made at a time when confi dence was dwindling in Hong Kong due to a battered economy and in the aft ermath of the SARS epidemic outbreak,1 Kung Fu Hustle (Gongfu, 2004), the highly acclaimed action comedy by Stephen Chow, can be seen as an attempt to revitalize the positive energy and tenacious resolve—what is commonly referred to as the “Hong Kong spirit” (Xianggang jingshen)—that has allegedly pro- pelled the city’s amazing socioeconomic growth. -

Martial Arts, Acting and Kung Fu Hero in Change

EnterText 6.1 SABRINA YU Can a Wuxia Star Act? Martial Arts, Acting, and Critical Responses to Jet Li’s Once Upon A Time In China Introduction It has been commonplace in western critical discourse to state that action stars can’t act. This seems particularly true when it comes to trans-bordering Chinese action stars like Jet Li. Criticism of his acting skills in his English-language films can be easily picked up from the press: Without the fight scenes, though, this film (Romeo Must Die) would be a bust… ‘Jet is our special effect,’ says Silver, summing up his star’s appeal neatly.1 Li’s martial arts skills are as brilliant as his acting skills aren’t.2 The action is fun and ultra-violent, the story is satisfactorily ridiculous and the acting is non-existent.3 “Good martial artist with limited acting ability” seems to represent a popular view of Chinese martial arts stars and indeed this is how they are often used in Hollywood films. Nevertheless, such a view also reveals a deep-rooted bias, i.e. the martial arts star is someone who knows less about acting than s/he does about fighting. On the other hand, it reflects a dominant idea about film performance, by privileging facial Sabrina Yu: Can a Wuxia Star Act? 134 EnterText 6.1 expression/psychology over body movement/physicality. Can’t a martial arts star act? Are fighting and acting always two split, conflicting elements within a Chinese wuxia star’s performance? In this paper, I would like to re-examine this stereotypical western critical consensus in the light of the contrasting Hong Kong critical response to Jet Li’s Chinese work Once Upon A Time In China (Tsui Hark, Hong Kong, 1991) (OUATIC hereinafter). -

Music Video for WEEK ENDING OCTOBER 10, 1999 P R O G R a M M I N G Billboard Video Monitor

Music Video FOR WEEK ENDING OCTOBER 10, 1999 P R O G R A M M I N G Billboard Video Monitor. THE MOST-PLAYED CLIPS AS MONITORED BY BROADCAST DATA SYSTEMS NEW ONS" ARE REPORTED BY THE NETWORKS (NOT BY BDS) FOR THE WEEK AHEAD Seagal To Host Video Awards; C MUSIC 55555t ISI OH. 1MUSIC FIRST Disney Seeks Acts For Series 14 hours daily Continuous programming Continuous programming Continuous programming 1899 9th Street NE, 2806 Opryland Dr., 1515 Broadway, NY, NY 10036 1515 Broadway, NY, NY 10036 Washington, D.C. 20018 Nashville, TN 37214 B ILLBOARD MUSIC VIDEO ON THE MOVE: The Box has I Blink 182, All The Small Things 1 Lou Bega, Mambo No. 5 1 Martina McBride, I Love You 2 Mariah Carey, Heartbreaker 1 Eve, Gotta Man 2 Smash Mouth, All Star CONFAB: We're counting down made the following promotions: 2 Dwight Yoakam, Thinking About 3 Britney Spears, (You Drive Me) Crazy 2 a -Tip, Vivrant Thing Leaving 3 Red Hot Chili Peppers, Scar Tissue 3 Brad Paisley, He Didn't Have To Be 4 Backstreet Boys, Larger Than Life moved 3 Jay -Z, Girls' Best Friend 4 Santana Feat. Rob Thomas, Smooth to another exciting Billboard Liz Kiley has up to VP of 4 Mark Wills, She's In Love 5 TLC, Unpretty 4 Mobb Deep, Quiet Storm 5 Lenny Kravitz, American Woman 5 Montgomery Gentry, Lonely & Gone 6 Brandy, U Don't Know Me Music Video Conference and radio and broadcast affiliations; 5 Snoop Dogg, B- Please 7 Jennifer Lopez, Waiting For Tonight 6 Fiona Apple, Fast As You Can 6 Chad Brock, Lightning Does The Work 6 Puff Daddy Feat.