Virtual Landscapes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Asian Stereotypes in Games

ASIAN STEREOTYPES in VIDEO GAMES BY YICHEN SHOU STEREOTYPE ster·e·o·type noun a widely held but fixed and oversimplified image or idea of a particular type of person or thing. Major Asian Stereotypes 1. Charlie Chan: Emasculated, weak and obedient, characters of this “good” Asian-male stereotype are often non-threatening and exist only to foil the superiority of the protagonist. 2. Fu Manchu: Cunning, cruel and grotesque, this Asian-male stereotype embodies the fear of the “Yellow Peril” and is usually revealed to be the evil mastermind behind plots to destroy the West. 3. China Doll: Weak, submissive and hyper-sexualized, this “good” Asian-female stereotype often plays the role of romanic interests needing rescue and are easily replaced by non-Asian romantic interests. 4. KungFu Master: Despite being strong and capable, this character is often a desexualized sidekick whose martial arts expertise is only justified by their (usually Chinese) heritage. 5. Samurai/Ninja: A stereotype mainly reserved for the Japanese, these katana/ninja-star wielding characters are emotionless, fearless, fanatically loyal to their masters, and obsessed with the concept of honor. 6. Dragon Lady: The “evil” counterpart of the China Doll, these hyper-sexualized Asian-females are temptresses who use deception and sex appeal to further their evil plans. Gender Nature Characteristic Stereotype Character (Non-Playable) Character (Playable) Chen Lin Jin Jie Tong Si Hung Bo’ Rai Cho Bioshock: Innite Battleeld 4 Deus Ex: Human Revolution Mortal Kombat Cheng Lorck Raymond -

The Development and Validation of the Game User Experience Satisfaction Scale (Guess)

THE DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF THE GAME USER EXPERIENCE SATISFACTION SCALE (GUESS) A Dissertation by Mikki Hoang Phan Master of Arts, Wichita State University, 2012 Bachelor of Arts, Wichita State University, 2008 Submitted to the Department of Psychology and the faculty of the Graduate School of Wichita State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2015 © Copyright 2015 by Mikki Phan All Rights Reserved THE DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF THE GAME USER EXPERIENCE SATISFACTION SCALE (GUESS) The following faculty members have examined the final copy of this dissertation for form and content, and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy with a major in Psychology. _____________________________________ Barbara S. Chaparro, Committee Chair _____________________________________ Joseph Keebler, Committee Member _____________________________________ Jibo He, Committee Member _____________________________________ Darwin Dorr, Committee Member _____________________________________ Jodie Hertzog, Committee Member Accepted for the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences _____________________________________ Ronald Matson, Dean Accepted for the Graduate School _____________________________________ Abu S. Masud, Interim Dean iii DEDICATION To my parents for their love and support, and all that they have sacrificed so that my siblings and I can have a better future iv Video games open worlds. — Jon-Paul Dyson v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Althea Gibson once said, “No matter what accomplishments you make, somebody helped you.” Thus, completing this long and winding Ph.D. journey would not have been possible without a village of support and help. While words could not adequately sum up how thankful I am, I would like to start off by thanking my dissertation chair and advisor, Dr. -

The Effect of Dynamic Music in Video Games an Overview of Current Research

The Effect of Dynamic Music in Video Games An Overview of Current Research Department of Game Design Author: Léo F. Smith Bachelor’s Thesis in Game Design, 15 c Program: Game Design and Project Management Supervisors: Mikael Fridenfalk, Hans Svensson Examiner: Masaki Hayashi May 2020 Abstract Historically, game audio has been a peripheral feature in game development that has significantly evolved in recent years. Music as a meaningful emotional and narrative conveyor has become a central element in contemporary video games. Dynamic music, sound that is able to flexibly and smoothly adapt to the game state and interact with the player’s in-game actions, is at the forefront of a new era of music composition in games. This survey paper examines the experiential nature of games and the effect of dynamic music on the player’s audial experience. It looks at game design theory, immersion, the function of game music, sound perception, and the challenges of game music. Then, it presents compositional methods of dynamic music and practical insights on FMOD Studio as a middleware. Furthermore, current research on how dynamic music affects the player experience and future adaptations are explored. It concludes that the increasing need of dynamic music producers will precipitate innovation and research in novel domains such as biometric feedback systems and augmented/virtual reality. As dynamic music expands outside of the gaming sphere, it is likely to become a ubiquitous form of media that we will interact with in the future. Keywords: interactive music, adaptive music, dynamic music, emotion, game music, generative music, music, player experience, video games. -

Achieve Your Vision

ACHIEVE YOUR VISION NE XT GEN ready CryENGINE® 3 The Maximum Game Development Solution CryENGINE® 3 is the first Xbox 360™, PlayStation® 3, MMO, DX9 and DX10 all-in-one game development solution that is next-gen ready – with scalable computation and graphics technologies. With CryENGINE® 3 you can start the development of your next generation games today. CryENGINE® 3 is the only solution that provides multi-award winning graphics, physics and AI out of the box. The complete game engine suite includes the famous CryENGINE® 3 Sandbox™ editor, a production-proven, 3rd generation tool suite designed and built by AAA developers. CryENGINE® 3 delivers everything you need to create your AAA games. NEXT GEN ready INTEGRATED CryENGINE® 3 SANDBOX™ EDITOR CryENGINE® 3 Sandbox™ Simultaneous WYSIWYP on all Platforms CryENGINE® 3 SandboxTM now enables real-time editing of multi-platform game environments; simul- The Ultimate Game Creation Toolset taneously making changes across platforms from CryENGINE® 3 SandboxTM running on PC, without loading or baking delays. The ability to edit anything within the integrated CryENGINE® 3 SandboxTM CryENGINE® 3 Sandbox™ gives developers full control over their multi-platform and simultaneously play on multiple platforms vastly reduces the time to build compelling content creations in real-time. It features many improved efficiency tools to enable the for cross-platform products. fastest development of game environments and game-play available on PC, ® ® PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360™. All features of CryENGINE 3 games (without CryENGINE® 3 Sandbox™ exception) can be produced and played immediately with Crytek’s “What You See Is What You Play” (WYSIWYP) system! CryENGINE® 3 Sandbox™ was introduced in 2001 as the world’s first editor featuring WYSIWYP technology. -

Free Tools Photosynth

Free Tools Photosynth Making a Photosynth Creating the best synth starts with the right photos. Here are some key tips: • Take overlapping panoramas from different locations • Have lots of overlap between shots to get good matching • Limit the angles between photos (no more than 25 degrees – at least 15 per full rotation) • Pick scenes or objects with lots of detail and texture • Don’t crop your images before synthing • Rotate your photos to be ‘up’ correctly before synthing Once you have signed in, click the Upload button (top right of page) or click on the Create your Synth icon on the home page. (scroll down). If you do not have the software you will be prompted to download it first. Once it is installed you will see the Create a Synth button. You will see a pop-up window with Start a new synth button. Give your synth a name, tags (descriptive words) and description. Click Add Photos, browse to your files add them. Then click on the Synth button at the bottom of the page. Photosynth will do the rest for you. Making a Panorama Many photosynths consist of photos shot from a single location. Our friends in Microsoft Research have developed a free, world class panoramic image stitcher called Microsoft Image Composite Editor (ICE for short.) ICE takes a set of overlapping photographs of a scene shot from a single camera location, and creates a single high-resolution image. Photosynth now has support for uploading, exploring and viewing ICE panoramas alongside normal synths. Here’s how to create a panorama in ICE and upload it to Photosynth: 1. -

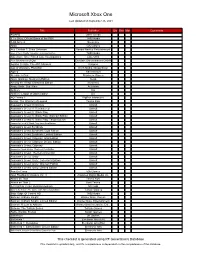

Microsoft Xbox One

Microsoft Xbox One Last Updated on September 26, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments #IDARB Other Ocean 8 To Glory: Official Game of the PBR THQ Nordic 8-Bit Armies Soedesco Abzû 505 Games Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown Bandai Namco Entertainment Aces of the Luftwaffe: Squadron - Extended Edition THQ Nordic Adventure Time: Finn & Jake Investigations Little Orbit Aer: Memories of Old Daedalic Entertainment GmbH Agatha Christie: The ABC Murders Kalypso Age of Wonders: Planetfall Koch Media / Deep Silver Agony Ravenscourt Alekhine's Gun Maximum Games Alien: Isolation: Nostromo Edition Sega Among the Sleep: Enhanced Edition Soedesco Angry Birds: Star Wars Activision Anthem EA Anthem: Legion of Dawn Edition EA AO Tennis 2 BigBen Interactive Arslan: The Warriors of Legend Tecmo Koei Assassin's Creed Chronicles Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III: Remastered Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: Walmart Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: Target Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: GameStop Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate: Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate: Limited Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey: Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey: Deluxe Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Origins: Steelbook Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: The Ezio Collection Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Collector's Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Walmart Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Limited Edition Ubisoft Assetto Corsa 505 Games Atari Flashback Classics Vol. 3 AtGames Digital Media Inc. -

Crysis 2 Full Hd Patch

Crysis 2 full hd patch click here to download All three Crysis 2 DirectX 11 Ultra Upgrade files are available to download via a fast, queue-free server. You are free to download the DirectX 11 update and high resolution packs, however, as they work with all versions of the game – just ensure you're patched to version before installing them. Hi-Res Texture Pack. Enhance your copy of Crysis 2 with the DirectX 11 Ultra Upgrade. This pack has three files: the Patch , DirectX 11 Ultra Upgrade and High Resolution Texture Pack. Extreme Immersive Mod v + New TOD Demostartion | Crysis Max Settings | Directx 10 | p. This is a gameplay for Crysis 2 with High Resolution Texture Pack with patch , using DirectX 11 Ho. C:\Program Files (x86)\Steam\SteamApps\common\Crysis 2 Game of the Year\patch you already have this Patches. Download the DirectX 11 Ultra Upgrade and the High Resolution Texture Pack After Installation you have to That means a complete new Story for free! The Game itself is not needed! I'm pretty sure at some point in the future, Crysis 2 will be in a Steam or Origin sale. And you might buy it and then be sickened to the core by the vile March level graphics. Ugh, I'm embarrassed that we accepted it as a game back then, with its DX11 shaders and an official HD texture pack that looks as. The high-rez pack is definitely a must if you wanna see Crysis 2 in its full glory! The DX11 patch as well, i play crysis2 and the hd pack is a hindrance on multiplayer you need best fps and they will reduce yours by a good 30%+ even when you turn everything down to minimum. -

EA and Crytek Recruit Players Into Free Trial for Crysis Wars

EA and Crytek Recruit Players Into Free Trial for Crysis Wars New Players Can Experience the Critically-Acclaimed Multiplayer Action GameFree from April 9- April 17 and Get the Complete Crysis CompilationCrysis Maximum EditionStarting May 5 REDWOOD CITY, Calif., Apr 09, 2009 (BUSINESS WIRE) -- Electronic Arts Inc. (NASDAQ:ERTS) and Crytek GmbH announced the start of a free trial period for Crysis Wars(R)*, the multiplayer game for Crysis Warhead(R), the award-winning first-person shooter originally released last Fall. Starting today, gamers can play all of Crysis Wars** online for free including each of the game's three action-packed multiplayer modes and all 23 maps. The free trial period runs until Friday, April 17, 2009. This trial is designed to give players a sample of the signature action and visuals that only the Crysis(R) series delivered. For those players that want more than just a sample, EA and Crytek will release Crysis(R) Maximum Edition, a compilation of all three Crysis games in one box (Crysis, Crysis Warhead and Crysis Wars). Available beginning May 5th for the MSRP of $39.99, Crysis Maximum Edition is the ultimate Crysis experience. "When Crysis Wars was released seven months ago, one of our biggest goals was to be able to deliver continued support to our growing multiplayer community," said Cevat Yerli, CEO and President of Crytek. "We think we have delivered on that promise, not only by releasing new content, fixes and our powerful MOD SDK, but also by continuing to offer these types of free trials." Crysis Wars supports matches for up to 32 players and contains three distinct gameplay modes; InstantAction, frenetic deathmatch enhanced by the power of the nanosuit, PowerStruggle, a hardcore team-based mode and TeamInstantAction, a mix of fast-paced action in a team-based environment. -

EA and Crytek Launches Crysis Warhead in North America and Europe

EA and Crytek Launches Crysis Warhead in North America and Europe The Next Installment of the Award-Winning Crysis Franchise Arrives at Retail Stores This Week REDWOOD CITY, Calif., Sep 16, 2008 (BUSINESS WIRE) -- Electronic Arts Inc. (NASDAQ:ERTS) and Crytek GmbH announced today that Crysis Warhead(R), the next installment in the award-winning Crysis(R) franchise, has shipped to retailers in North America and Europe and will hit store shelves and participating digital download services starting September 18, 2008 exclusively for the PC. Containing a new single player campaign featuring Crytek's trademark open-ended gameplay and stunning visuals along with Crysis Wars(R), the exciting new multiplayer suite for the Crysis universe, Crysis Warhead is a tremendous value at only $29.99 and does not require the original Crysis to play. "The launch of Crysis Warhead marks a significant milestone for the entire Crytek family," said Cevat Yerli, CEO and President of Crytek. "The team at Crytek Hungary has delivered a dynamic and intense single player experience more than worthy of the Crysis franchise, while the multiplayer team in Frankfurt has revisited and extended multiplayer in the Crysis universe with Crysis Wars. They are both great representations of our studio's core values of technical excellence, craftsmanship and quality." "Crytek is a world-class partner and quickly becoming one of the most formidable independent developers in the industry," said David DeMartini, Senior Vice President and General Manager of EA Partners. "Crysis was one of the best games of last year and we are thrilled to have the opportunity to bring Crysis Warhead, a game that actually improves upon Crysis' core experience, to the largest possible audience on a global stage." Crysis Warhead takes place alongside the events of last year's critical hit, with players experiencing the explosive battles against waves of challenging enemies on the other side of the island through the eyes and nanosuit of the bold and aggressive Sergeant "Psycho" Sykes. -

Game Developer Index 2010 Foreword

SWEDISH GAME INDUSTRY’S REPORTS 2011 Game Developer Index 2010 Foreword It’s hard to imagine an industry where change is so rapid as in the games industry. Just a few years ago massive online games like World of Warcraft dominated, then came the breakthrough for party games like Singstar and Guitar Hero. Three years ago, Nintendo turned the gaming world upside-down with the Wii and motion controls, and shortly thereafter came the Facebook games and Farmville which garnered over 100 million users. Today, apps for both the iPhone and Android dominate the evolution. Technology, business models, game design and marketing changing almost every year, and above all the public seem to quickly embrace and follow all these trends. Where will tomorrow’s earnings come from? How can one make even better games for the new platforms? How will the relationship between creator and audience change? These and many other issues are discussed intensively at conferences, forums and in specialist press. Swedish success isn’t lacking in the new channels, with Minecraft’s unprecedented success or Battlefield Heroes to name two examples. Independent Games Festival in San Francisco has had Swedish winners for four consecutive years and most recently we won eight out of 22 prizes. It has been touted for two decades that digital distribution would outsell traditional box sales and it looks like that shift is finally happening. Although approximately 85% of sales still goes through physical channels, there is now a decline for the first time since one began tracking data. The transformation of games as a product to games as a service seems to be here. -

Mobilizing (Ourselves) for a Critical Digital Archaeology Adam Rabinowitz University of Texas at Austin, [email protected]

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Mobilizing the Past Art History 10-21-2016 5.2. Response: Mobilizing (Ourselves) for a Critical Digital Archaeology Adam Rabinowitz University of Texas at Austin, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/arthist_mobilizingthepast Part of the Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons Recommended Citation Rabinowitz, Adam. “Response: Mobilizing (Ourselves) for a Critical Digital Archaeology.” In Mobilizing the Past for a Digital Future: The Potential of Digital Archaeology, edited by Erin Walcek Averett, Jody Michael Gordon, and Derek B. Counts, 493-518. Grand Forks, ND: The Digital Press at the University of North Dakota, 2016. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mobilizing the Past by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MOBILIZING THE PAST FOR A DIGITAL FUTURE MOBILIZING the PAST for a DIGITAL FUTURE The Potential of Digital Archaeology Edited by Erin Walcek Averett Jody Michael Gordon Derek B. Counts The Digital Press @ The University of North Dakota Grand Forks Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons By Attribution 4.0 International License. 2016 The Digital Press @ The University of North Dakota Book Design: Daniel Coslett and William Caraher Cover Design: Daniel Coslett Library of Congress Control Number: 2016917316 The Digital Press at the University of North Dakota, Grand Forks, North Dakota ISBN-13: 978-062790137 ISBN-10: 062790137 Version 1.1 (updated November 5, 2016) Table of Contents Preface & Acknowledgments v How to Use This Book xi Abbreviations xiii Introduction Mobile Computing in Archaeology: Exploring and Interpreting Current Practices 1 Jody Michael Gordon, Erin Walcek Averett, and Derek B. -

Three Theories of Just War: Understanding Warfare As a Social Tool Through Comparative Analysis of Western, Chinese, and Islamic Classical Theories of War

THREE THEORIES OF JUST WAR: UNDERSTANDING WARFARE AS A SOCIAL TOOL THROUGH COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF WESTERN, CHINESE, AND ISLAMIC CLASSICAL THEORIES OF WAR A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN PHILOSOPHY MAY 2012 By Faruk Rahmanović Thesis Committee: Tamara Albertini, Chairperson Roger T. Ames James D. Frankel Brien Hallett Keywords: War, Just War, Augustine, Sunzi, Sun Bin, Jihad, Qur’an DEDICATION To my parents, Ahmet and Nidžara Rahmanović. To my wife, Majda, who continues to put up with me. To Professor Keith W. Krasemann, for teaching me to ask the right questions. And to Professor Martin J. Tracey, for his tireless commitment to my success. 1 ABSTRACT The purpose of this analysis was to discover the extent to which dictates of war theory ideals can be considered universal, by comparing the Western (European), Classical Chinese, and Islamic models. It also examined the contextual elements that drove war theory development within each civilization, and the impact of such elements on the differences arising in war theory comparison. These theories were chosen for their differences in major contextual elements, in order to limit the impact of contextual similarities on the war theories. The results revealed a great degree of similarities in the conception of warfare as a social tool of the state, utilized as a sometimes necessary, albeit tragic, means of establishing peace justice and harmony. What differences did arise, were relatively minor, and came primarily from the differing conceptions of morality and justice within each civilization – thus indicating a great degree of universality to the conception of warfare.