The Reception of Copernicus As Reflected in Biographies **

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The science of the stars in Danzig from Rheticus to Hevelius / Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7n41x7fd Author Jensen, Derek Publication Date 2006 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO THE SCIENCE OF THE STARS IN DANZIG FROM RHETICUS TO HEVELIUS A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History (Science Studies) by Derek Jensen Committee in charge: Professor Robert S. Westman, Chair Professor Luce Giard Professor John Marino Professor Naomi Oreskes Professor Donald Rutherford 2006 The dissertation of Derek Jensen is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm: _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2006 iii FOR SARA iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page........................................................................................................... iii Dedication ................................................................................................................. iv Table of Contents ...................................................................................................... v List of Figures .......................................................................................................... -

Who Were the Prusai ?

WHO WERE THE PRUSAI ? So far science has not been able to provide answers to this question, but it does not mean that we should not begin to put forward hypotheses and give rise to a constructive resolution of this puzzle. Great help in determining the ethnic origin of Prusai people comes from a new branch of science - genetics. Heraldically known descendants of the Prusai, and persons unaware of their Prusai ethnic roots, were subject to the genetic test, thus provided a knowledge of the genetics of their people. In conjunction with the historical knowledge, this enabled to be made a conclusive finding and indicated the territory that was inhabited by them. The number of tests must be made in much greater number in order to eliminate errors. Archaeological research and its findings also help to solve this question, make our knowledge complemented and compared with other regions in order to gain knowledge of Prusia, where they came from and who they were. Prusian people provinces POMESANIA and POGESANIA The genetic test done by persons with their Pomesanian origin provided results indicating the Haplogroup R1b1b2a1b and described as the Atlantic Group or Italo-Celtic. The largest number of the people from this group, today found between the Irish and Scottish Celts. Genetic age of this haplogroup is older than that of the Celt’s genetics, therefore also defined as a proto Celtic. 1 The Pomerania, Poland’s Baltic coast, was inhabited by Gothic people called Gothiscanza. Their chronicler Cassiodor tells that they were there from 1940 year B.C. Around the IV century A.D. -

Nicolaus Copernicus Immanuel Kant

NICOLAUS COPERNICUS IMMANUEL KANT The book was published as part of the project: “Tourism beyond the boundaries – tourism routes of the cross-border regions of Russia and North-East Poland” in the part of the activity concerning the publishing of the book “On the Trail of Outstanding Historic Personages. Nicolaus Copernicus – Immanuel Kant” 2 Jerzy Sikorski • Janusz Jasiński ON THE TRAIL OF OUTSTANDING HISTORIC PERSONAGES NICOLAUS COPERNICUS IMMANUEL KANT TWO OF THE GREATEST FIGURES OF SCIENCE ON ONCE PRUSSIAN LANDS “ElSet” Publishing Studio, Olsztyn 2020 PREFACE The area of former Prussian lands, covering the southern coastal strip of the Baltic between the lower Vistula and the lower Nemunas is an extremely complicated region full of turmoil and historical twists. The beginning of its history goes back to the times when Prussian tribes belonging to the Balts lived here. Attempts to Christianize and colonize these lands, and finally their conquest by the Teutonic Order are a clear beginning of their historical fate and changing In 1525, when the Great Master relations between the Kingdom of Poland, the State of the Teutonic Order and of the Teutonic Order, Albrecht Lithuania. The influence of the Polish Crown, Royal Prussia and Warmia on the Hohenzollern, paid homage to the one hand, and on the other hand, further state transformations beginning with Polish King, Sigismund I the Old, former Teutonic state became a Polish the Teutonic Order, through Royal Prussia, dependent and independent from fief and was named Ducal Prussia. the Commonwealth, until the times of East Prussia of the mid 20th century – is The borders of the Polish Crown since the times of theTeutonic state were a melting pot of events, wars and social transformations, as well as economic only changed as a result of subsequent and cultural changes, whose continuity was interrupted as a result of decisions partitions of Poland in 1772, 1793, madeafter the end of World War II. -

Narratio Prima Or First Account of the Books on the Revolution By

Foreword It is with great pleasure that we can present a facsimile edition of the Narratio Prima by Georg Joachim Rheticus. This book, an abstract and resumé of Nicolaus Copernicus’ De Revoltionibus, was written when both these schol- ars were staying at Lubawa Castle in the summer of 1539. Their host was a friend of Copernicus, Tiedemann Giese, the Bishop of Culm. Published three years before the work of Copernicus, the Narratio Prima recounts, in a clear and concise manner, the heliocentric theory of the great Polish scholar. We have also prepared the first-ever translation of Rheticus’ book for Polish readers, published in its own separate volume. Several years ago, I had an interesting discussion with Professor Jarosław 5 Włodarczyk from the Institute for the History of Science at the Polish Academy of Sciences about the significance of the time Nicolaus Copernicus spent in the land of Lubawa. It is this charming land, shaped by a melting glacier, that the Nicolaus Copernicus Foundation, whose works I am hon- oured to oversee, has chosen for its seat. It is also here that the Nicolaus Copernicus Foundation has constructed its two astronomical observatories, in Truszczyny and Kurzętnik. It was at Lubawa Castle that Nicolaus Copernicus, persuaded by his friends Giese and Rheticus, decided to publish his work. This canonical book was later to become one of the milestones of modern science. Moreover, it Narratio prima or First Account of the Books “On the Revolutions”… is in Lubawa that Rheticus, amazed by the groundbreaking theory exposed by his teacher in De Revolutionibus, wrote his own book. -

Besprechungen Und Anzeigen 453 Das Litauische Recht Nach Der

Besprechungen und Anzeigen 453 das litauische Recht nach der Eroberung des größten Teils der Kiever Rus’ durch das li- tauische Großfürstentum beeinflusst hatte, lässt sich kaum als „ausländisch“ bezeichnen. Es ließen sich noch mehr Beispiele anführen. So wirken die nachgezeichneten Einflüsse zumindest für die ältere Privatrechtsgeschichte anachronistisch. Der Vf. kommt immerhin seiner Aufgabe, die wichtigsten Daten der allgemeinen politi- schen Geschichte, der äußeren Rechtsgeschichte und der ausgewählten Beispiele aus den früheren Forschungen zu den zivilrechtlichen Quellen aus der baltischen Region zusam- menzuführen, relativ fleißig nach. Für einen Einstieg in das Thema und als eine zusam- menfassende Erläuterung älterer Forschungen nicht nur auf Deutsch, sondern auch auf Russisch, Polnisch, Weißrussisch und Litauisch ist das Buch gut brauchbar. Tartu Marju Luts-Sootak Pietro Umberto Dini: Aliletoescvr. Linguistica baltica delle origini. Teorie e contesti linguistici nel Cinquecento. Books & Company. Livorno 2010. 844 S. ISBN 978-88-7997- 115-7. (€ 50,–.) This volume by the Italian Baltist Pietro Umberto D i n i reveals new horizons not only in the studies of Baltic languages, but also in the spread of humanist ideas in the culture of the Baltic region. The monograph is appealing and relevant for scholars of various fields of human sciences. This recent work has an intriguing title and extends over an imposing number of pages. The large size of this book meets the eye, as well as the research mentioned in the intro- duction at the Niedersächsische Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek in Göttingen and the W. F. Bessel Award of the Alexander von Humboldt-Stiftung, which undoubtedly contributed to the preparation of this monograph. -

The Nicolaus Copernicus Grave Mystery. a Dialog of Experts

POLISH ACADEMY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES The Nicolaus Copernicus On 22–23 February 2010 a scientific conference “The Nicolaus Copernicus grave mystery. A dialogue of experts” was held in Kraków. grave mystery The institutional organizers of the conference were: the European Society for the History of Science, the Copernicus Center for Interdisciplinary Studies, the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences with its two commissions (the Commission on the History of Science, and the Commission on the Philosophy of Natural Sciences), A dialogue of experts the Institute for the History of Science of the Polish Academy of Sciences, and the Tischner European University. Edited by Michał Kokowski The purpose of this conference was to discuss the controversy surrounding the discovery of the grave of Nicolaus Copernicus and the identification of his remains. For this reason, all the major participants of the search for the grave of Nicolaus Copernicus and critics of these studies were invited to participate in the conference. It was the first, and so far only such meeting when it was poss- ible to speak openly and on equal terms for both the supporters and the critics of the thesis that the grave of the great astronomer had been found and the identification of the found fragments of his skeleton had been completed. [...] In this book, we present the aftermath of the conference – full texts or summa- ries of them, sent by the authors. In the latter case, where possible, additional TERRA information is included on other texts published by the author(s) on the same subject. The texts of articles presented in this monograph were subjected to sev- MERCURIUS eral stages of review process, both explicit and implicit. -

High Clergy and Printers: Antireformation Polemic in The

bs_bs_banner High clergy and printers: anti-Reformation polemic in the kingdom of Poland, 1520–36 Natalia Nowakowska University of Oxford Abstract Scholarship on anti-Reformation printed polemic has long neglected east-central Europe.This article considers the corpus of early anti-Reformation works produced in the Polish monarchy (1517–36), a kingdom with its own vocal pro-Luther communities, and with reformed states on its borders. It places these works in their European context and, using Jagiellonian Poland as a case study, traces the evolution of local polemic, stresses the multiple functions of these texts, and argues that they represent a transitional moment in the Polish church’s longstanding relationship with the local printed book market. Since the nineteen-seventies, a sizeable literature has accumulated on anti-Reformation printing – on the small army of men, largely clerics, who from c.1518 picked up their pens to write against Martin Luther and his followers, and whose literary endeavours passed through the printing presses of sixteenth-century Europe. In its early stages, much of this scholarship set itself the task of simply mapping out or quantifying the old church’s anti-heretical printing activity. Pierre Deyon (1981) and David Birch (1983), for example, surveyed the rich variety of anti-Reformation polemical materials published during the French Wars of Religion and in Henry VIII’s England respectively.1 John Dolan offered a panoramic sketch of international anti-Lutheran writing in an important essay published in 1980, while Wilbirgis Klaiber’s landmark 1978 database identified 3,456 works by ‘Catholic controversialists’ printed across Europe before 1600.2 This body of work triggered a long-running debate about how we should best characterize the level of anti-Reformation printing in the sixteenth century. -

Things, That Endure

CULTURE, PHILOSOPHY AND ARTS RESEARCH INSTITUTE Ancient Baltic Culture THINGS, THAT ENDURE Edited by Dr. Elvyra Usačiovaitė Vilnius 2009 KULTŪROS, FILOSOFIJOS IR MENO INSTITUTAS Senovės baltų kultūra TAI, KAS IŠLIEKA Vilnius 2009 UDK 008(=88) Se91 Knygos leidimą parėmė Lietuvos Respublikos švietimo ir mokslo ministerija Redakcinė kolegija: akademikas Algirdas GAIŽUTIS Vilniaus pedagoginis universitetas prof, habil, dr. Juris URTANAS Latvijos kultūros akademija habil, dr. Saulius AMBRAZAS Lietuvių kalbos institutas habil, dr. Nijolė LAURINKIENĖ Lietuvių literatūros ir tautosakos institutas akademike Janina KURSYTĖ Latvijos universitetas dr. Radvile RACĖNAITĖ Lietuvių literatūros ir tautosakos institutas dr. Elvyra USAČIOVAITĖ Kultūros, filosofijos ir meno institutas dr. Eugenijus SVETIKAS Lietuvos istorijos institutas Sudarė dr. E. Usačiovaitė. Leidinys apsvarstytas ir rekomenduotas spaudai Kultūros, filosofijos ir meno instituto tarybos © Kultūros, filosofijos ir meno institutas, 2009 © Viršelio nuotrauka, Vilmantė Matuliauskienė, 2009 © „Kronta“ leidykla, 2009 ISBN 978-609-401-027-9 Turinys Elvyra Usačiovaitė. Įvadas............................................................9 Gintaras Beresnevičius Vietos ir spalvos Lietuvos religinės geografijos bruožai XIII-XIV a.................... 31 Elvyra Usačiovaitė. Kristupas Hartknochas apie prūsų religiją.........................................................................39 Pranas Vildžiūnas. Auxtheias Vissagistis - supagonintas krikščionių Dievas........................................................................69 -

AUKCJA VARIA (28) 16 Lutego (Sobota) 2019, Godz

AUKCJA VARIA (28) 16 lutego (sobota) 2019, godz. 17.00 w galerii Sopockiego Domu Aukcyjnego w Gdańsku, ul. Długa 2/3 WYSTAWA PRZEDAUKCYJNA: od 28 stycznia 2019 r. Gdańsk, ul. Długa 2/3 poniedziałek – piątek 10–18, sobota 11–15 tel. (58) 301 05 54 Katalog dostępny na stronie: www.sda.pl 1 Artysta nieokreślony (2 poł. XVIII w.) Pejzaż włoski olej, płótno dublowane, 45,5 × 75 cm cena wywoławcza: 5 000 zł 2 SOPOCKI DOM AUKCYJNY 2 Artysta nieokreślony (2 poł. XVIII w.) Pejzaż włoski z ruinami i posągiem olej, płótno dublowane, 45,5 × 75 cm cena wywoławcza: 5 000 zł AUKCJA VARIA (28) | MALARSTWO 3 3 Thomas Bush Hardy (1842 Sheffield–1897 Londyn) Żaglowce na morzu olej, płótno, 51 × 76 cm sygn. p. d.: T… Hardy cena wywoławcza: 3 000 zł 4 SOPOCKI DOM AUKCYJNY 4 Carl Saltzmann (1947–1923) Statki na redzie, 1898 r. olej, płótno, 53,5 × 117 cm sygn. i dat. l. d.: C. Saltzmann 98 cena wywoławcza: 1 900 zł AUKCJA VARIA (28) | MALARSTWO 5 5 Zbigniew Litwin (1914–2001) Łodzie na plaży, 1968 r. akwarela, papier, 36 × 51 cm sygn. i dat. p. d.: ZLitwin 1968 cena wywoławcza: 2 600 zł • 6 J. Makowski (XX w.) Jastarnia olej, tektura, 21 × 31 cm sygn. p. d.: J. Ma- kowski/Jastarnia cena wywoławcza: 1 000 zł 6 SOPOCKI DOM AUKCYJNY 7 Marian Mokwa (1889 Malary – 1987 Sopot) Port olej, płótno, 50 × 80 cm sygn. p. d.: Mokwa cena wywoławcza: 10 000 zł • AUKCJA VARIA (28) | MALARSTWO 7 8 Stanisław Gibiński (1882 Rzeszów – 1971 Katowice) Przy ognisku akwarela, tektura, 34 × 48,5 cm sygn. -

Bulletin 26Iii Sonderegger

UNEXPECTED ASPECTS OF ANNIVERSARIES or: Early sundials, widely travelled HELMUT SONDEREGGER his year my hometown, Feldkirch in Germany, cel- Iserin was appointed town physician and all of his family ebrates the 500th anniversary of Rheticus. He was were accepted as citizens of Feldkirch. Georg, a man with T the man who published the first report on Coperni- widespread interests, owned a considerable number of cus’s new heliocentric view of the world. Subsequently, he books and a collection of alchemical and medical instru- helped Copernicus complete his manuscript for publication ments. Over the years, superstitious people suspected this and arranged its printing in Nürnberg. When I planned my extraordinary man of being a sorcerer in league with attendance at the BSS Conference 2014 at Greenwich, I sources of darkness. asked myself if there could be any connections between the A few weeks before his appointment as town physician, on th th 25 BSS anniversary and the 500 anniversary of Rheticus’ 16 Feb 1514, his only son Georg Joachim was born. When birth. And now in fact, I have found a really interesting the son was 14 his father was accused of betraying his story! patients and, additionally, of being a swindler and klepto- maniac. He was sentenced to death and subsequently Feldkirch 500 Years Ago beheaded by the sword. His name Iserin was officially Feldkirch, a small district capital of about 30,000 people, is erased by so-called ‘damnatio memoriae’. His wife and situated in the very west of Austria close to Switzerland children changed their name to the mother’s surname. -

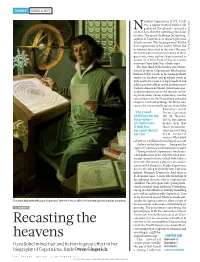

Recasting the Heavens

COMMENT BOOKS & ARTS icolaus Copernicus (1473–1543) was a quintessential unifier. He gathered the planets around a Ncentral Sun, thereby inventing the Solar System. The grand challenge facing biog- raphers of Copernicus is that few personal details survive. Was he gregarious? Did he have a girlfriend in his youth? When did he become interested in the stars? Because the historical record answers none of these questions, some authors have resorted to STOCK GEOGRAPHIC J.-L. HUENS/NATIONAL fiction. In A More Perfect Heaven, science historian Dava Sobel has it both ways. The first third of the book is strictly his- torical. It traces Copernicus’s life from his birth in Polish Toruń, to his undergraduate studies in Kraków and graduate work in Italy, and to his career as a legal, medical and administrative officer in the northernmost Catholic diocese of Poland. Sobel makes par- ticularly effective use of the records surviv- ing from when Canon Copernicus was the rent collector for the Frauenburg cathedral chapter’s vast land holdings. To fill the nar- rative, she occasionally quotes from John Banville’s novel “The grand Doctor Copernicus challenge facing (W. W. Norton, biographers 1976), but always of Copernicus makes clear that is that few those reconstruc- personal details tions are not taken survive.” from archival sources. What Sobel achieves is a brilliant chronological account — the best in the literature — laying out the stages of Copernicus’s administrative career. Having reached Copernicus’s final years, when publication of his still unfinished man- uscript seemed to have stalled, Sobel takes a new tack. -

Ewa Bojaruniec-Król

Medieval Studies, vol. 22, 2018 / Studia z Dziejów Średniowiecza, tom 22, 2018 Ewa Bojaruniec-Król (Museum of Gdańsk) https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5846-747X Ewa Bojaruniec-Król The ennoblement of Gdańsk patricians in the second half of the fifteenth century and the early sixteenth century The ennoblement of Gdańsk patricians… Keywords: The ennonblement, Gdańsk, Kazimierz Jagiellończyk, coats of arms, Hansa The Thirteen Years’ War of 1454–1466, fought between Poland and the Teutonic Order, resulted in Pomerelia and Gdańsk becoming part of the Kingdom of Poland.1 In recognition of Gdańsk’s con- tribution to the war effort against the Teutonic Order, the King of Poland, Kazimierz Jagiellończyk (Casimir IV Jagiellon), awarded the city four privileges.2 Issued in the period between 1454 and 1457, 1 K. Górski, Pomorze w dobie wojny trzynastoletniej [Pomerania at the time of the Thirteen Years’ War], Poznań 1932, pp. 117–256; M. Biskup, ‘Walka o zjednoczenie Pomorza Wschodniego z Polską w połowie XV wieku’ [The struggle for Pomerelia’s unification with Poland in the latter half of the fifteenth century], in: Szkice z dziejów Pomorza, vol. 1, Pomorze średniowieczne, ed. G. Labuda, Warszawa 1958, pp. 354–368; idem, Zjednoczenie Pomorza Wschodniego z Polską w połowie XV wieku [The unification of Pomerelia with Poland in the fifteenth century], Warszawa 1959, pp. 278–331; idem, Trzynastoletnia wojna z zakonem krzyżackim 1454–1466 [The Thirteen Years’ War with the Teutonic Order, 1454–1466], Warszawa 1967, passim; H. Samsonowicz, ‘Gdańsk w okresie wojny trzynastoletniej’ [Gdańsk during the Thirteen Years’ War], in: Historia Gdańska (hereinafter: HG), vol. 2, ed.