Deconstructivist Architecture Philip Johnson and Mark Wigley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pritzker Architecture Prize Laureate

For publication on or after Monday, March 29, 2010 Media Kit announcing the 2010 PritzKer architecture Prize Laureate This media kit consists of two booklets: one with text providing details of the laureate announcement, and a second booklet of photographs that are linked to downloadable high resolution images that may be used for printing in connection with the announcement of the Pritzker Architecture Prize. The photos of the Laureates and their works provided do not rep- resent a complete catalogue of their work, but rather a small sampling. Contents Previous Laureates of the Pritzker Prize ....................................................2 Media Release Announcing the 2010 Laureate ......................................3-5 Citation from Pritzker Jury ........................................................................6 Members of the Pritzker Jury ....................................................................7 About the Works of SANAA ...............................................................8-10 Fact Summary .....................................................................................11-17 About the Pritzker Medal ........................................................................18 2010 Ceremony Venue ......................................................................19-21 History of the Pritzker Prize ...............................................................22-24 Media contact The Hyatt Foundation phone: 310-273-8696 or Media Information Office 310-278-7372 Attn: Keith H. Walker fax: 310-273-6134 8802 Ashcroft Avenue e-mail: [email protected] Los Angeles, CA 90048-2402 http:/www.pritzkerprize.com 1 P r e v i o u s L a u r e a t e s 1979 1995 Philip Johnson of the United States of America Tadao Ando of Japan presented at Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C. presented at the Grand Trianon and the Palace of Versailles, France 1996 1980 Luis Barragán of Mexico Rafael Moneo of Spain presented at the construction site of The Getty Center, presented at Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Teresa Hubbard 1St Contact Address

CURRICULUM VITAE Teresa Hubbard 1st Contact address William and Bettye Nowlin Endowed Professor Assistant Chair Studio Division University of Texas at Austin College of Fine Arts, Department of Art and Art History 2301 San Jacinto Blvd. Station D1300 Austin, TX 78712-1421 USA [email protected] 2nd Contact address 4707 Shoalwood Ave Austin, TX 78756 USA [email protected] www.hubbardbirchler.net mobile +512 925 2308 Contents 2 Education and Teaching 3–5 Selected Public Lectures and Visiting Artist Appointments 5–6 Selected Academic and Public Service 6–8 Selected Solo Exhibitions 8–14 Selected Group Exhibitions 14–20 Bibliography - Selected Exhibition Catalogues and Books 20–24 Bibliography - Selected Articles 24–28 Selected Awards, Commissions and Fellowships 28 Gallery Representation 28–29 Selected Public Collections Teresa Hubbard, Curriculum Vitae - 1 / 29 Teresa Hubbard American, Irish and Swiss Citizen, born 1965 in Dublin, Ireland Education 1990–1992 M.F.A., Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, Halifax, Canada 1988 Yale University School of Art, MFA Program, New Haven, Connecticut, USA 1987 Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Skowhegan, Maine, USA 1985–1988 University of Texas at Austin, BFA Degree, Austin, Texas, USA 1983–1985 Louisiana State University, Liberal Arts, Baton Rouge, USA Teaching 2015–present Faculty Member, European Graduate School, (EGS), Saas-Fee, Switzerland 2014–present William and Bettye Nowlin Endowed Professor, Department of Art and Art History, College of Fine Arts, University of Texas -

Ankommen in Der Deutschen Lebenswelt

Europäisches Journal Europäisches Journal für Minderheitenfragen für Minderheitenfragen Contents Vol 9 No 1-2 2016 Editorial. 5 EJM Geleitwort Rita Süssmuth, Präsidentin a. D. des Deutschen Bundestages . 23 0 Hinführung . 27 Europäisches Journal für Minderheitenfragen 1 Kulturpolitik: das dritte Politikfeld gelingender Integration . 61 2 Zur Theorie der Kulturaneignung . .119 Vol 9 No 1-2 2016 3 Wie sind Menschen eigentlich? Anthropologische Möglichkeiten und Grenzen von Migranten-Enkulturation durch Kunst und Kultur . .157 4 Herausforderungen an das Kulturaneignungssystem . 175 Vol 9 No 1-2 2016 1-2 Vol 9 No Matthias Theodor Vogt, Erik Fritzsche, Christoph Meißelbach 5 Vier Experten-Ansichten. 217 5.1 Johann Heinrich Gottlob Justi 217 Ankommen 5.2 Siegfried Deinege 228 5.3 Werner J. Patzelt 236 in der deutschen Lebenswelt 5.4 Anton Sterbling 267 6 Die Sicht von Verantwortungsträgern in Wirtschaft, Migranten-Enkulturation und regionale Resilienz Politik und Kultur . 277 in der Einen Welt 7 Handlungsempfehlungen für eine erneuerte Migrations- und Integrationspolitik . 325 Nachwort Olaf Zimmermann, Geschäftsführer des Deutschen Kulturrates . 425 ISSN (Print) 1865-1089 ISSN (Online) 1865-1097 ISBN (Print) 978-3-8305-3716-8 ISBN (E-Book) 978-3-8305-2975-0 Europäisches Journal für Minderheitenfragen Vol 9 No 1-2 2016 Matthias Theodor Vogt, Erik Fritzsche, Christoph Meißelbach Ankommen in der deutschen Lebenswelt Migranten-Enkulturation und regionale Resilienz in der Einen Welt unter Mitarbeit von Sebastian Trept, Anselm Vogler, Simon Cremer, Jan Albrecht mit Beiträgen von Johann H. G. Justi, Siegfried Deinege, Werner J. Patzelt, Anton Sterbling und zahlreichen Verantwortungsträgern aus Wirtschaft, Politik und Kultur Geleitwort von Rita Süssmuth Nachwort von Olaf Zimmermann BWV • BERLINER WISSENSCHAFTS-VERLAG © BWV • BERLINER WISSENSCHAFTS-VERLAG GmbH Urheberrechtlich geschütztes Material. -

Philip Johnson, Architecture, and the Rebellion of the Text: 1930-1934

PHILIP JOHNSON, ARCHITECTURE, AND THE REBELLION OF THE TEXT: 1930-1934 The architect Philip Johnson, intermittently famous for provocative buildings— his modernist Glass House, 1949, and the Postmodern AT&T (now Sony) Building, 1984—will be remembered less for his architecture than for his texts. He first made a reputation as co-author (with Henry Russell Hitchcock) of the 1932 book The Interna- tional Style, which presented the European Modern Movement as a set of formal rules and documented its forms in photographs. In 1947, on the verge of a career in archi- tectural practice, Johnson authored the first full-length monograph on Mies van der Rohe. To these seminal texts in modernism’s history in America should be added a number of occasional writings and lectures on modern architecture. In addition, the exhibitions on architecture and design Johnson curated for the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), beginning with the seminal Modern Architecture in 1932, should also be considered texts, summarizing, or reducing, architectural experience through selected artifacts and carefully crafted timelines. In the course of a very long career, Johnson was under almost constant fire for de-radicalizing modernism, for reducing it to yet another value-free episode in the history of style, or even of taste. The nonagenarian Johnson himself cheerfully con- fessed to turning the avant-garde he presented to America into “just a garde” (qtd. in Somol 43). Yet in 1931 Johnson described the spirit of his campaign for modernism as “the romantic love for youth in revolt, especially in art, universal today” (Johnson, Writings 45). -

On a Gently Sloping Site in New Canaan, Sanaa Designed Spaces Text Photos for Public Gatherings in the Form of a Meandering River

164 Mark 59 Long Section Sanaa New Canaan — CT — USA 165 Si!ing Lightly on the Land On a gently sloping site in New Canaan, Sanaa designed spaces Text Photos for public gatherings in the form of a meandering river. Michael Webb Iwan Baan 166 Mark 59 Long Section Sanaa New Canaan — CT — USA 167 In essence, the building of glass, concrete, steel and wood is a single long roof that seems to float above the surface of the ground as it twists and turns across the landscape. &e amphitheatre in the foreground seats 700. A few kilometres from Philip Johnson’s Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut, Sanaa has created a structure that is even more transparent and immaterial. Aptly named the River, it comprises a canopy of Douglas fir, supported on slender steel poles, that descends a gentle slope in a series of switchbacks, widening at five points to embrace rounded glass enclosures that seem as insubstantial as soap bubbles. From one end to the other is 140 m, but it is tucked into a space half that length. From above, the gently bowed roof of anodized aluminium panels picks up the light as though it were a watercourse, and constantly shi$ing perspectives give it a sense of motion. %is linear shelter was commissioned by the non-profit Grace Farms Foundation to house its non-denominational worship space, as a gathering place for the communi& and as a belvedere from which to observe a 32-hectare nature preserve. %eir first impulse was to save this last undeveloped plot of countryside in Fairfield Coun&. -

Foster + Partners Bests Zaha Hadid and OMA in Competition to Build Park Avenue Office Tower by KELLY CHAN | APRIL 3, 2012 | BLOUIN ART INFO

Foster + Partners Bests Zaha Hadid and OMA in Competition to Build Park Avenue Office Tower BY KELLY CHAN | APRIL 3, 2012 | BLOUIN ART INFO We were just getting used to the idea of seeing a sensuous Zaha Hadid building on the corporate-modernist boulevard that is Manhattan’s Park Avenue, but looks like we’ll have to keep dreaming. An invited competition to design a new Park Avenue office building for L&L Holdings and Lemen Brothers Holdings pitted starchitect against starchitect (with a shortlist including Hadid and Rem Koolhaas’s firm OMA). In the end, Lord Norman Foster came out victorious. “Our aim is to create an exceptional building, both of its time and timeless, as well as being respectful of this context,” said Norman Foster in a statement, according to The Architects’ Newspaper. Foster described the building as “for the city and for the people that will work in it, setting a new standard for office design and providing an enduring landmark that befits its world-famous location.” The winning design (pictured left) is a three-tiered, 625,000-square-foot tower. With sky-high landscaped terraces, flexible floor plates, a sheltered street-level plaza, and LEED certification, the building does seem to reiterate some of the same principles seen in the Lever House and Seagram Building, Park Avenue’s current office tower icons, but with markedly updated standards. Only time will tell if Foster’s building can achieve the same timelessness as its mid-century predecessors, a feat that challenged a slew of architects as Park Avenue cultivated its corporate identity in the 1950s and 60s. -

Benjamin and Koolhaas: History’S Afterlife Frances Hsu

65 Benjamin and Koolhaas: History’s Afterlife Frances Hsu Paris Benjamin intended his arcades project to be politi- Walter Benjamin called Paris the capital of the cally revolutionary. He worked on his opus while living nineteenth century. In his eponymous exposi- dangerously under Fascism as a refugee in Paris, tory exposé, written between 1935 and 1939, where, unable to secure an academic position, he he outlines a project to uncover the reality of the wrote for newspapers under various German pseu- recent past, the pre-history of modernity, through donyms. He had solicited support from the Institute the excavation of the ideologies, i.e., dreamworlds, for Social Research that was re-established in New embodied in material and cultural artefacts of the York in 1934 in association with Columbia University. nineteenth century. He used images to create a His project was unfinished at the end of the 1930s. history that would illuminate the contemporaneous He had collected numerous artefacts, drawings, workings of capital that had created the dreamlands photographs, texts, letters and papers – images of the city. The loci for the production of dream- reflecting the life of poets, artists, writers, workers, worlds were the arcades – pedestrian passages, engineers and others. He had also produced many situated between two masonry structures, that loose, handwritten pages organised into folders were lined on both sides with cafés, shops and that catalogued not only his early exposés but also other amusements and typically enclosed by an literary and philosophical passages from nineteenth iron and glass roof. Over three hundred arcades century sources and his observations, commen- were once scattered throughout the urban fabric taries and reflections for a theory and method of of Paris. -

Johnny O'neal

OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM BOBDOROUGH from bebop to schoolhouse VOCALS ISSUE JOHNNY JEN RUTH BETTY O’NEAL SHYU PRICE ROCHÉ Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 NEw York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JOHNNY O’NEAL 6 by alex henderson [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JEN SHYU 7 by suzanne lorge General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The Cover : BOB DOROUGH 8 by marilyn lester Advertising: [email protected] Encore : ruth price by andy vélez Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : betty rochÉ 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : southport by alex henderson US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEwS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] obituaries Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Festival Report Stuart Broomer, Robert Bush, 13 Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, special feature 14 by andrey henkin Anders Griffen, Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, CD ReviewS 16 Suzanne Lorge, Mark Keresman, Marc Medwin, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, Miscellany 41 John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Event Calendar Contributing Writers 42 Brian Charette, Ori Dagan, George Kanzler, Jim Motavalli “Think before you speak.” It’s something we teach to our children early on, a most basic lesson for living in a society. -

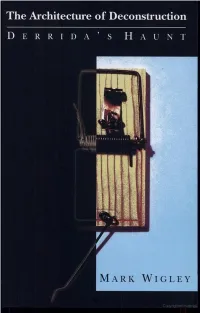

The Architecture of Deconstruction: Derrida's Haunt

The Architecture o f Deconstruction: Derrida’s Haunt Mark Wigley The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England Fifth printing, 1997 First M IT Press paperback edition, 1995 © 1993 M IT Press Ml rights reserved. No part o f this book may be reproduced in any form by any elec tronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information stor age and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. This book was printed and bound in the United States o f America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Wigley, Mark. The architecture of deconstruction : Derrida’s haunt / Mark Wigley. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-262-23170-0 (H B ), 0-262-73114-2 (PB) 1. Deconstruction (Architecture) 2. Derrida, Jacques—Philosophy. I. T itle . NA682.D43W54 1993 720'. 1—dc20 93-10352 CIP For Beatriz and Andrea Any house is a fa r too com plicated, clumsy, fussy, mechanical counter feit of the human body . The whole interior is a kind of stomach that attempts to digest objects . The whole life o f the average house, it seems, is a sort of indigestion. A body in ill repair, suffering indispo sition—constant tinkering and doctoring to keep it alive. It is a marvel, we its infesters, do not go insane in it and with it. Perhaps it is a form of insanity we have to put in it. Lucky we are able to get something else out of it, thought we do seldom get out of it alive ourselves. —Frank Lloyd Wright ‘The Cardboard House,” 1931. -

Pritzker Prize to Doshi, Designer for Humanity in Search of a Win-Win

03.19.18 GIVING VOICE TO THOSE WHO CREATE WORKPLACE DESIGN & FURNISHINGS Pritzker Prize to Doshi, Designer for Humanity The 2018 Pritzker Prize, universally considered the highest honor for an architect, will be conferred this year on the 90-year- old Balkrishna Doshi, the first Indian so honored. The citation from the Pritzker jury recognizes his particular strengths by stating that he “has always created architecture that is serious, never flashy or a follower of trends.” The never-flashy-or-trendy message is another indication from these arbiters of design that our infatuation with exotic three-dimensional configurations initiated by Frank Gehry and Zaha Hadid – and emulated by numerous others – may have run its course. FULL STORY ON PAGE 3… In Search of a Win-Win: The Value Engineering Process When most design professionals hear the term value engineering, a dreaded sinking feeling deep in the pit of their stomach ensues. Both the design firm and the contractor are at a disadvantage in preserving the look and design intent of the project, keeping construction costs to a minimum, and delivering the entire package on time. officeinsight contributorPeter Carey searches for solutions that make it all possible. FULL STORY ON PAGE 14… Concurrents – Environmental Psychology: Swedish Death Cleaning First, Chunking Second Swedish death cleaning has replaced hygge as the hottest Scandinavian life management tool in the U.S. Margareta CITED: Magnussen’s system for de-cluttering, detailed in her book, The “OUR FATE ONLY SEEMS Gentle Art of Swedish Death Cleaning: How to Make Your Loved HORRIBLE WHEN WE PLACE Ines’ Lives Easier and Your Own Life More Pleasant, is a little IT IN CONTRAST WITH more straightforward than Marie Kondo’s more sentimental tact, SOMETHING THAT WOULD SEEM PREFERABLE.” described in The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up. -

The Abuse of Architectonics by Decorating in an Era After Deconstructivism

THE ABUSE OF ARCHITECTONICS BY DECORATING IN AN ERA AFTER DECONSTRUCTIVISM DECONSTRUCTION OF THE TECTONIC STRUCTURE AS A WAY OF DECORATION PIM GERRITSEN | 1186272 MSC3 | INTERIORS, BUILDINGS, CITIES | STUDIO BACK TO SCHOOL AR0830 ARCHITECTURE THEORY | ARCHITECTURAL THINKING | GRADUATION THESIS FALL SEMESTER 2008-2009 | MARCH 09 THESIS | ARCHITECTURAL THINKING | AR0830 | PIM GERRITSEN | 1186272 | MAR-09 | P. 1 ‘In fact, all architecture proceeds from structure, and the first condition at which it should aim is to make the outward form accord with that structure.’ 1 Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc (1872) Lectures Everything depends upon how one sets it to work… little by little we modify the terrain of our work and thereby produce new configurations… it is essential, systematic, and theoretical. And this in no way minimizes the necessity and relative importance of certain breaks of appearance and definition of new structures…’ 2 Jacques Derrida (1972) Positions ‘It is ironic that the work of Coop Himmelblau, and of other deconstructive architects, often turns out to demand far more structural ingenuity than works developed with a ‘rational’ approach to structure.’ 3 Adrian Forty (2000) Words and Buildings Theme In recent work of architects known as deconstructivists the tectonic structure of the buildings seems to be ‘deconstructed’ in order to decorate the building’s image. In other words: nowadays deconstruction has become a style with the architectonic structure used as decoration. Is the show of architectonic elements in recent work of -

Rem Koolhaas: an Architecture of Innovation Daniel Fox

Lehigh University Lehigh Preserve Volume 16 - 2008 Lehigh Review 2008 Rem Koolhaas: An Architecture of Innovation Daniel Fox Follow this and additional works at: http://preserve.lehigh.edu/cas-lehighreview-vol-16 Recommended Citation Fox, Daniel, "Rem Koolhaas: An Architecture of Innovation" (2008). Volume 16 - 2008. Paper 8. http://preserve.lehigh.edu/cas-lehighreview-vol-16/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Lehigh Review at Lehigh Preserve. It has been accepted for inclusion in Volume 16 - 2008 by an authorized administrator of Lehigh Preserve. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rem Koolhaas: An Architecture of Innovation by Daniel Fox 22 he three Master Builders (as author Peter Blake refers to them) – Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, and Frank Lloyd Wright – each Drown Hall (1908) had a considerable impact on the architec- In 1918, a severe outbreak ture of the twentieth century. These men of Spanish Influenza caused T Drown Hall to be taken over demonstrated innovation, adherence distinct effect on the human condi- by the army (they had been to principle, and a great respect for tion. It is Koolhaas’ focus on layering using Lehigh’s labs for architecture in their own distinc- programmatic elements that leads research during WWI) and tive ways. Although many other an environment of interaction (with turned into a hospital for Le- architects did indeed make a splash other individuals, the architecture, high students after St. Luke’s during the past one hundred years, and the exterior environment) which became overcrowded. Four the Master Builders not only had a transcends the eclectic creations students died while battling great impact on the architecture of of a man who seems to have been the century but also on the archi- influenced by each of the Master the flu in Drown.