Out and in Harm's Way: Sexual Minority Students' Psychological

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Certainty (Uber Gewissheit) Ed

Ludwig Wittgenstein On Certainty (Uber Gewissheit) ed. G.E.M.Anscombe and G.H.von Wright Translated by Denis Paul and G.E.M.Anscombe Basil Blackwell, Oxford 1969-1975 Preface What we publish here belongs to the last year and a half of Wittgenstein's life. In the middle of 1949 he visited the United States at the invitation of Norman Malcolm, staying at Malcolm's house in Ithaca. Malcolm acted as a goad to his interest in Moore's 'defence of common sense', that is to say his claim to know a number of propositions for sure, such as "Here is one hand, and here is another", and "The earth existed for a long time before my birth", and "I have never been far from the earth's surface". The first of these comes in Moore's 'Proof of the External World'. The two others are in his 'Defence of Common Sense'; Wittgenstein had long been interested in these and had said to Moore that this was his best article. Moore had agreed. This book contains the whole of what Wittgenstein wrote on this topic from that time until his death. It is all first-draft material, which he did not live to excerpt and polish. The material falls into four parts; we have shown the divisions at #65, #192, #299. What we believe to be the first part was written on twenty loose sheets of lined foolscap, undated. These Wittgenstein left in his room in G.E.M.Anscombe's house in Oxford, where he lived (apart from a visit to Norway in the autumn) from April 1950 to February 1951. -

The Complete Stories

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka a.b.e-book v3.0 / Notes at the end Back Cover : "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. Page 1 The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. -

The Moody Blues Tour / Set List Project - Updated April 9, 2006

The Moody Blues Tour / Set List Project - updated April 9, 2006 compiled by Linda Bangert Please send any additions or corrections to Linda Bangert ([email protected]) and notice of any broken links to Neil Ottenstein ([email protected]). This listing of tour dates, set lists, opening acts, additional musicians was derived from many sources, as noted on each file. Of particular help were "Higher and Higher" magazine and their website at www.moodies- magazine.com and the Moody Blues Official Fan Club (OFC) Newsletters. For a complete listing of people who contributed, click here. Particular thanks go to Neil Ottenstein, who hosts these pages, and to Bob Hardy, who helped me get these pages converted to html. One-off live performances, either of the band as a whole or of individual members, are not included in this listing, but generally can be found in the Moody Blues FAQ in Section 8.7 - What guest appearances have the band members made on albums, television, concerts, music videos or print media? under the sub-headings of "Visual Appearances" or "Charity Appearances". The current version of the FAQ can be found at www.toadmail.com/~notten/FAQ-TOC.htm I've construed "additional musicians" to be those who played on stage in addition to the members of the Moody Blues. Although Patrick Moraz was legally determined to be a contract player, and not a member of the Moody Blues, I have omitted him from the listing of additional musicians for brevity. Moraz toured with the Moody Blues from 1978 through 1990. From 1965-1966 The Moody Blues were Denny Laine, Clint Warwick, Mike Pinder, Ray Thomas and Graeme Edge, although Warwick left the band sometime in 1966 and was briefly replaced with Rod Clarke. -

Skipping Is an Activity That Usually Goes on in a Group, Although It Can Be Done Alone

THE SINGING GAMES OF MUNSTER CHILDREN JOHN BUCKLEY Skipping--A Definition Skipping is an activity that usually goes on in a group, although it can be done alone. Skipping is usually associated with girls, but boys also join in depending on the context and circumstances. A shorter rope can be used if only one person is skipping while a longer rope is used for group skipping. The beat or rhythm of the rhyme dictates the rhythm of the skip or jump. The rhythm or pace of the jump or skip is also influenced by the beat of the rope against the surface of the ground that's being skipped on. This relationship between the rhythm of the rhyme and the turning of the rope is very important because if the coordination between the two is lost, the flow is interrupted causing the rope to be tripped up thereby stopping proceedings. The Language of Skipping Girls have their own terminology associated with skipping. For instance, in Cork City, if you are not skipping but instead are turning the rope for those skipping, you are known to be "on the rope." If, while skipping, a girl causes the rope to stop, the term used is that she has "downed the rope." When the suggestion in a group is announced to skip, or to "play skipping," shouts of "begs not on" (again heard by Cork children) might be heard, which means that the person doesn't want to be one of the group to turn the rope for the others to skip. There can also be pre-skipping rituals, such as the reciting of a counting-out rhyme or the wrapping of the rope with the bend between the thumb and first finger being one end and just above a bent elbow of one group members being the other end for the rope to be wrapped. -

Travels with Jottings. from Midland to the Pacific. Letters by E.D. Holton

Travels with jottings. From midland to the Pacific. Letters by E.D. Holton. Written for, and published chiefly, as souvenirs to personal acquaintances and friends TRAVELS WITH JOTTINGS. FROM MIDLAND TO THE PACIFIC. LETTERS BY E. D. HOLTON. Written for, and Published, Chiefly, as Souvenirs to Personal Acquaintances and Friends. MILWAUKEE: Trayser Brothers, Printers, 62 Oneida Street, Grand Opera House. 1880. LETTER I. Canon City—Journey Across Iowa and Kansas. Travels with jottings. From midland to the Pacific. Letters by E.D. Holton. Written for, and published chiefly, as souvenirs to personal acquaintances and friends http://www.loc.gov/resource/calbk.096 CANON CITY, Colorado, December 16, 1879. Three weeks to-morrow marks the time since, with my wife and little grandson (a lad six years old), I left our good city on a tramp to the Pacific Coast with no other object—save some considerations of health for the little boy—than to mark with one's own eyes, the marvelous strides which our republican civilization has made between the shores of Lake Michigan and the coast of the Pacific Ocean and the fortieth and forty-fifth degree of north latitude, within that period of time when in my young manhood I became a citizen of the then little village of Milwaukee now so grand, so strong, and beautiful a city. Our first stop was made at Delavan, where we took our thanksgiving dinner with the large family of one hundred and fifty mute children—and a happier family you will seldom find. In passing, I am happy to say that the improvised buildings made by the trustees of this Institution since the great calamity of the fire, were so far in use as to promise safety and comfort to the large number of inmates, and afford almost undiminished facilities for the prosecution of the great purposes for which the institution was founded, to-wit: the education of this unfortunate but deeply interesting class of children of the State, who cannot be educated in the public schools. -

Édith Piaf: a Cultural History

ÉDITH PIAF: A CULTURAL HISTORY ÉDITH PIAF A Cultural History David Looseley LIVERPOOL UNIVERSITY PRESS Édith Piaf: A Cultural History First published 2015 by Liverpool University Press 4 Cambridge Street Liverpool L69 7ZU Copyright © 2015 David Looseley The right of David Looseley to be identified as the author of this book has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication data A British Library CIP record is available print ISBN 978-1-78138-257-8 epdf ISBN 978-1-78138-425-1 Typeset by Carnegie Book Production, Lancaster Printed in the UK by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY. Contents CONTENTS Acknowledgements vii Chronology 1 Introduction 15 part i: narrating piaf 1 Inventing la Môme 27 2 Piaf and her public 45 3 A singer at war 65 part ii: piaf and chanson 4 A new Piaf 83 5 High art, low culture: Piaf and la chanson française 97 6 Ideology, tragedy, celebrity: a new middlebrow 113 part iii: afterlives 7 Losing Piaf 135 8 Remembering Piaf 153 9 Performing Piaf 171 Conclusion 185 Notes 193 References 233 Index 243 v For my granddaughter Elizabeth (Lizzie) Looseley-Burnet, with love Acknowledgements Acknowledgements would like to express my gratitude to the following, who in I various ways have helped me with the research for this book: Jacques d’Amboise, Ewan Burnet, Erica Burnham of the University of London in Paris, Di Holmes, Jim House, John and Josette Hughes, the late Tony Judt, Rhiannon Looseley, Bernard Marchois of the Musée Édith Piaf, Sue Miller, Cécile Obligi of the Bibliothèque nationale’s Département des arts du spectacle, Cécile Prévost-Thomas, Keith Reader, Philip Tagg, Florence Tamagne and Vera Zolberg. -

Close Only Counts Three Favorite Tracks on the Record, “Occupational Hazard,” “Con- Grit of Kim Gordon and Bouncy Drone of Chrissie Hynde

-----------------------------------------Spins --------------------------------------- Wooden Nickel Mark Hutchins CD of the Week Liar’s Gift BACKTRACKS $9.99 It was 2003, and I was working Moody Blues at a record store when a guy who To Our Children’s Children’s Children (1969) looked like he could’ve been in then- hot indie band Grandaddy fumbled The Moody Blues tended to go big; big in. He looked around, said nothing, arrangements, big lyrics and always big then approached the counter. Peek- concept albums. This release, inspired by ing from below the lid of his ball the July ’69 moon landing, perhaps the hu- cap, the possibly-bearded mystery man race’s biggest accomplishment to that point, was the fifth man asked if we had any copies of an obscure record called Please studio release from The Moody Blues. by a band called Vandolah. “Yeah, we do,” I said, “and it’s so good. It opens with “Higher And Higher,” sort of a garbled mess of Do you need a copy?” spoken word and guitars. It’s vintage Moody Blues and kicks off Before I finished my sentence the guy was halfway out the door. one of the best prog-rock records they ever did. The track carries “No,” he said, “just checking.” A couple years later, with the release you into “Eyes Of A Child,” which sounds like early Pink Floyd, of Vandolah’s second album, Walk It Off, I saw that guy again. On followed by the poppy folk-psychedelic “Floating.” Next come a $11.99 stage. Singing Vandolah songs. A couple of years after that I got to couple of bridge pieces before side one finishes with Mike Pin- know Mark Hutchins, the one-time frontman/songwriter/guitarist der’s “Out And In” and his dreamy mellotron. -

Mind in the Making Prescription

MIND IN THE MAKING PRESCRIPTIONS FOR LEARNING Cover FOCUS AND SELF CONTROL The Seven Essential Life Skills Every Child Needs PRESCRIPTIONS FOR LEARNING Spoiling Baby Promoting Focus and Self Control in Infants Four Strategies That Work in Moving from Managing Children’s Behavior to Promoting Life Skills Question: My infant cries and is “fussy.” Will I spoil her if I respond to every cry? The American Academy of Pediatrics says a young infant cannot be “spoiled” by holding and cuddling. It is important to respond to your baby’s crying now because it actually will decrease clingy behavior later on. 1. See if your baby needs something. Babies communicate their basic NEEDS by fussing—they are too young to communicate their wants. To figure out what your daughter needs, become a detective. Ask yourself: • “Can I figure out WHAT she needs by watching?” Are there clues? For example, eye rubbing and glazed eyes probably mean your baby is tired. Rooting (trying to suck something) probably means your baby is hungry. Squirming may mean your baby needs changing. • “WHEN is my daughter most likely to get fussy?” Which situations tend to make her most upset (for example, loud noises, bright lights, lots of other people in the room)? Are there times of day when she is fussier than other times (after she has been awake for a few hours, before meal time)? When you understand what prompts fussiness, you can do your best to prevent these from getting out of hand (such as giving your baby a nap before he or she becomes exhausted). -

Variations on a Theme: Forty Years of Music, Memories, and Mistakes

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 5-15-2009 Variations on a Theme: Forty years of music, memories, and mistakes Christopher John Stephens University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Stephens, Christopher John, "Variations on a Theme: Forty years of music, memories, and mistakes" (2009). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 934. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/934 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Variations on a Theme: Forty years of music, memories, and mistakes A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts In Creative Non-Fiction By Christopher John Stephens B.A., Salem State College, 1988 M.A., Salem State College, 1993 May 2009 DEDICATION For my parents, Jay A. Stephens (July 6, 1928-June 20, 1997) Ruth C. -

Earth Science a Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of The

Earth Science A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Sarah E. Green May 2015 © 2015 Sarah E. Green. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Earth Science by SARAH E. GREEN has been approved for the Department of English and the College of Arts and Sciences by Mark Halliday Professor of English Robert Frank Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT GREEN, SARAH E., Ph.D., May 2015, English Earth Science Director of Dissertation: Mark Halliday “I Am Not Sentimental” looks at poems by Elizabeth Bishop, Adam Zagajewski, Robert Frost, Gregory Corso, and Rachel Wetzsteon, all of which have in common the speaker’s grappling with diametrically opposed ideas (ways of living, ways of seeing.) Though the speakers make divergent choices, in every case the poem is able to sincerely and substantively engage both sides of a dichotomy, before settling on a conclusive course of action or perception. This openness to paradox and/or counter-argument heightens the poems' poignancy, immediacy, and intellectual liveliness, creating the sense that in every case the poet is thinking in real time and as surprised by the outcome as the reader. “Earth Science” is a collection of poems that explores the ways in which life surprises us by disrupting simple categories: stranger and neighbor, lover and enemy, luck and loss. 4 DEDICATION Dedicated to my grandmother, Margaret W. Grimes 5 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thanks to Mark Halliday and Jill Rosser for their guidance. 6 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Abstract ............................................................................................................................ -

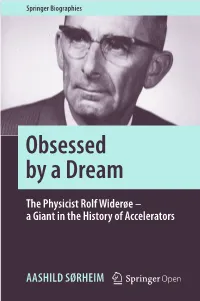

The Physicist Rolf Widerøe – a Giant in the History of Accelerators

Springer Biographies Obsessed by a Dream The Physicist Rolf Widerøe – a Giant in the History of Accelerators AASHILD SØRHEIM Springer Biographies Te books published in the Springer Biographies tell of the life and work of scholars, innovators, and pioneers in all felds of learning and throughout the ages. Prominent scientists and philosophers will feature, but so too will lesser known personalities whose signifcant contributions deserve greater recognition and whose remarkable life stories will stir and motivate readers. Authored by historians and other academic writers, the volumes describe and analyse the main achievements of their subjects in manner accessible to nonspecialists, interweaving these with salient aspects of the protagonists’ personal lives. Autobiographies and memoirs also fall into the scope of the series. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/13617 Aashild Sørheim Obsessed by a Dream The Physicist Rolf Widerøe – a Giant in the History of Accelerators Aashild Sørheim Oslo, Norway Translated by Frank Stewart, Bathgate, UK ISSN 2365-0613 ISSN 2365-0621 (electronic) Springer Biographies ISBN 978-3-030-26337-9 ISBN 978-3-030-26338-6 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-26338-6 Translation from the Norwegian language edition: Besatt av en drøm. Historien om Rolf Widerøe by Aashild Sørheim, © Forlaget Historie & Kultur AS, Oslo, Norway, 2015. All Rights Reserved. ISBN: 9788283230000 © Te Editor(s) (if applicable) and Te Author(s) 2020. Tis book is an open access publication. Open Access Tis book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if you modifed the licensed material. -

17-18 Student Handbook (2-5-2018)

STUDENT HANDBOOK 2017-2018 Culver Academies Welcome to Culver The development of character is a central component in Culver’s mission. Culver assists students in becoming responsible citizens and leaders through an education in the classic virtues – wisdom, courage, moderation, and justice. Leadership classes, opportunities to lead, and a culture that embraces our Code of Conduct and Honor Code complement the broader Culver curriculum, all of which provides the fertile environment for your individual growth. The Culver Mission Culver educates students for leadership and responsible citizenship in society by developing and nurturing the whole individual – mind, spirit and body – through an integrated curriculum that emphasizes the cultivation of character. The Culver Code of Conduct My aim in life is to become the best person I can be. To this end I will strive always to develop my potential to its fullest – physically, intellectually, morally and spiritually; to make wise choices, exercise self-discipline, and accept responsibility for my actions; to treat everyone as I would have them treat me; to fulfill the ideal of service to others; to place duty before self; to lead by example and take care of those I lead; and to live by the Culver Honor Code: I will not lie, cheat, or steal, and I will discourage others from such actions. TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1: Community Standards .............................................................................................. 5 Living the Culver Mission Adult Involvement in Students’ Lives Community Expectations Community of Mutual Respect A Community of Trust Commitment to Spiritual Development Chapter 2: Academics .................................................................................................................7 Academic Honors Academic Standards Eligibility Graduation Requirements Summer Study Attendance Policy Study Conditions Grade Reporting Schedule Chapter 3: Health and Safety ..................................................................................................