Alice Bag and Chola Con Cello

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grunge Is Dead Is an Oral History in the Tradition of Please Kill Me, the Seminal History of Punk

THE ORAL SEATTLE ROCK MUSIC HISTORY OF GREG PRATO WEAVING TOGETHER THE DEFINITIVE STORY OF THE SEATTLE MUSIC SCENE IN THE WORDS OF THE PEOPLE WHO WERE THERE, GRUNGE IS DEAD IS AN ORAL HISTORY IN THE TRADITION OF PLEASE KILL ME, THE SEMINAL HISTORY OF PUNK. WITH THE INSIGHT OF MORE THAN 130 OF GRUNGE’S BIGGEST NAMES, GREG PRATO PRESENTS THE ULTIMATE INSIDER’S GUIDE TO A SOUND THAT CHANGED MUSIC FOREVER. THE GRUNGE MOVEMENT MAY HAVE THRIVED FOR ONLY A FEW YEARS, BUT IT SPAWNED SOME OF THE GREATEST ROCK BANDS OF ALL TIME: PEARL JAM, NIRVANA, ALICE IN CHAINS, AND SOUNDGARDEN. GRUNGE IS DEAD FEATURES THE FIRST-EVER INTERVIEW IN WHICH PEARL JAM’S EDDIE VEDDER WAS WILLING TO DISCUSS THE GROUP’S HISTORY IN GREAT DETAIL; ALICE IN CHAINS’ BAND MEMBERS AND LAYNE STALEY’S MOM ON STALEY’S DRUG ADDICTION AND DEATH; INSIGHTS INTO THE RIOT GRRRL MOVEMENT AND OFT-OVERLOOKED BUT HIGHLY INFLUENTIAL SEATTLE BANDS LIKE MOTHER LOVE BONE, THE MELVINS, SCREAMING TREES, AND MUDHONEY; AND MUCH MORE. GRUNGE IS DEAD DIGS DEEP, STARTING IN THE EARLY ’60S, TO EXPLAIN THE CHAIN OF EVENTS THAT GAVE WAY TO THE MUSIC. THE END RESULT IS A BOOK THAT INCLUDES A WEALTH OF PREVIOUSLY UNTOLD STORIES AND FRESH INSIGHT FOR THE LONGTIME FAN, AS WELL AS THE ESSENTIALS AND HIGHLIGHTS FOR THE NEWCOMER — THE WHOLE UNCENSORED TRUTH — IN ONE COMPREHENSIVE VOLUME. GREG PRATO IS A LONG ISLAND, NEW YORK-BASED WRITER, WHO REGULARLY WRITES FOR ALL MUSIC GUIDE, BILLBOARD.COM, ROLLING STONE.COM, RECORD COLLECTOR MAGAZINE, AND CLASSIC ROCK MAGAZINE. -

Unobtainium-Vol-1.Pdf

Unobtainium [noun] - that which cannot be obtained through the usual channels of commerce Boo-Hooray is proud to present Unobtainium, Vol. 1. For over a decade, we have been committed to the organization, stabilization, and preservation of cultural narratives through archival placement. Today, we continue and expand our mission through the sale of individual items and smaller collections. We invite you to our space in Manhattan’s Chinatown, where we encourage visitors to browse our extensive inventory of rare books, ephemera, archives and collections by appointment or chance. Please direct all inquiries to Daylon ([email protected]). Terms: Usual. Not onerous. All items subject to prior sale. Payment may be made via check, credit card, wire transfer or PayPal. Institutions may be billed accordingly. Shipping is additional and will be billed at cost. Returns will be accepted for any reason within a week of receipt. Please provide advance notice of the return. Please contact us for complete inventories for any and all collections. The Flash, 5 Issues Charles Gatewood, ed. New York and Woodstock: The Flash, 1976-1979. Sizes vary slightly, all at or under 11 ¼ x 16 in. folio. Unpaginated. Each issue in very good condition, minor edgewear. Issues include Vol. 1 no. 1 [not numbered], Vol. 1 no. 4 [not numbered], Vol. 1 Issue 5, Vol. 2 no. 1. and Vol. 2 no. 2. Five issues of underground photographer and artist Charles Gatewood’s irregularly published photography paper. Issues feature work by the Lower East Side counterculture crowd Gatewood associated with, including George W. Gardner, Elaine Mayes, Ramon Muxter, Marcia Resnick, Toby Old, tattooist Spider Webb, author Marco Vassi, and more. -

Discography of the Mainstream Label

Discography of the Mainstream Label Mainstream was founded in 1964 by Bob Shad, and in its early history reissued material from Commodore Records and Time Records in addition to some new jazz material. The label released Big Brother & the Holding Company's first material in 1967, as well as The Amboy Dukes' first albums, whose guitarist, Ted Nugent, would become a successful solo artist in the 1970s. Shad died in 1985, and his daughter, Tamara Shad, licensed its back catalogue for reissues. In 1991 it was resurrected in order to reissue much of its holdings on compact disc, and in 1993, it was purchased by Sony subsidiary Legacy Records. 56000/6000 Series 56000 mono, S 6000 stereo - The Commodore Recordings 1939, 1944 - Billy Holiday [1964] Strange Fruit/She’s Funny That Way/Fine and Mellow/Embraceable You/I’ll Get By//Lover Come Back to Me/I Cover the Waterfront/Yesterdays/I Gotta Right to Sing the Blues/I’ll Be Seeing You 56001 mono, S 6001 stereo - Begin the Beguine - Eddie Heywood [1964] Begin the Beguine/Downtown Cafe Boogie/I Can't Believe That You're in Love with Me/Carry Me Back to Old Virginny/Uptown Cafe Boogie/Love Me Or Leave Me/Lover Man/Save Your Sorrow 56002 mono, S 6002 stereo - Influence of Five - Hawkins, Young & Others [1964] Smack/My Ideal/Indiana/These Foolish Things/Memories Of You/I Got Rhythm/Way Down Yonder In New Orleans/Stardust/Sittin' In/Just A Riff 56003 mono, S 6003 stereo - Dixieland-New Orleans - Teagarden, Davison & Others [1964] That’s A- Plenty/Panama/Ugly Chile/Riverboat Shuffle/Royal Garden Blues/Clarinet -

OTHER CAMP: RETHINKING CAMP, the 1990S, and the POLITICS of VISIBILITY

OTHER CAMP: RETHINKING CAMP, THE 1990s, AND THE POLITICS OF VISIBILITY By Sarah Margaret Panuska A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of English—Doctor of Philosophy 2019 ABSTRACT Other Camp: Rethinking Camp, the 1990s, and the Politics of Visibility By Sarah Margaret Panuska Other Camp pairs 1990s experimental media produced by lesbian, bi, and queer women with queer theory to rethink the boundaries of one of cinema’s most beloved and despised genres, camp. I argue that camp is a creative and political practice that helps communities of women reckon with representational voids. This project shows how primarily-lesbian communities, whether black or white, working in the 1990s employed appropriation and practices of curation in their camp projects to represent their identities and communities, where camp is the effect of juxtaposition, incongruity, and the friction between an object’s original and appropriated contexts. Central to Other Camp are the curation-centered approaches to camp in the art of LGBTQ women in the 1990s. I argue that curation— producing art through an assembly of different objects, texts, or artifacts and letting the resonances and tensions between them foster camp effects—is a practice that not only has roots within experimental approaches camp but deep roots in camp scholarship. Relationality is vital to the work that curation does as an artistic practice. I link the relationality in the practice of camp curation to the relation-based approaches of queer theory, Black Studies, and Decolonial theory. My work cultivates the curational roots at the heart of camp and different theoretical approaches to relationality in order to foreground the emergence of curational camp methodologies and approaches to art as they manifest in the work of Sadie Benning, G.B Jones, Kaucyila Brooke and Jane Cottis, Cheryl Dunye, and Vaginal Davis. -

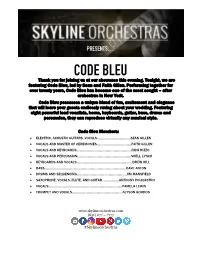

CODE BLEU Thank You for Joining Us at Our Showcase This Evening

PRESENTS… CODE BLEU Thank you for joining us at our showcase this evening. Tonight, we are featuring Code Bleu, led by Sean and Faith Gillen. Performing together for over twenty years, Code Bleu has become one of the most sought – after orchestras in New York. Code Bleu possesses a unique blend of fun, excitement and elegance that will leave your guests endlessly raving about your wedding. Featuring eight powerful lead vocalists, horns, keyboards, guitar, bass, drums and percussion, they can reproduce virtually any musical style. Code Bleu Members: • ELECTRIC, ACOUSTIC GUITARS, VOCALS………………………..………SEAN GILLEN • VOCALS AND MASTER OF CEREMONIES……..………………………….FAITH GILLEN • VOCALS AND KEYBOARDS..…………………………….……………………..RICH RIZZO • VOCALS AND PERCUSSION…………………………………......................SHELL LYNCH • KEYBOARDS AND VOCALS………………………………………..………….…DREW HILL • BASS……………………………………………………………………….….......DAVE ANTON • DRUMS AND SEQUENCING………………………………………………..JIM MANSFIELD • SAXOPHONE, VOCALS, FLUTE, AND GUITAR….……………ANTHONY POLICASTRO • VOCALS………………………………………………………………….…….PAMELA LEWIS • TRUMPET AND VOCALS……………….…………….………………….ALYSON GORDON www.skylineorchestras.com (631) 277 – 7777 #Skylineorchestras DANCE : BURNING DOWN THE HOUSE – Talking Heads BUST A MOVE – Young MC A GOOD NIGHT – John Legend CAKE BY THE OCEAN – DNCE A LITTLE LESS CONVERSATION – Elvis CALL ME MAYBE – Carly Rae Jepsen A LITTLE PARTY NEVER KILLED NOBODY – Fergie CAN’T FEEL MY FACE – The Weekend A LITTLE RESPECT – Erasure CAN’T GET ENOUGH OF YOUR LOVE – Barry White A PIRATE LOOKS AT 40 – Jimmy Buffet CAN’T GET YOU OUT OF MY HEAD – Kylie Minogue ABC – Jackson Five CAN’T HOLD US – Macklemore & Ryan Lewis ACCIDENTALLY IN LOVE – Counting Crows CAN’T HURRY LOVE – Supremes ACHY BREAKY HEART – Billy Ray Cyrus CAN’T STOP THE FEELING – Justin Timberlake ADDICTED TO YOU – Avicii CAR WASH – Rose Royce AEROPLANE – Red Hot Chili Peppers CASTLES IN THE SKY – Ian Van Dahl AIN’T IT FUN – Paramore CHEAP THRILLS – Sia feat. -

Dissertation

DISSERTATION Titel der Dissertation “We’re Punk as Fuck and Fuck like Punks:”* Queer-Feminist Counter-Cultures, Punk Music and the Anti-Social Turn in Queer Theory Verfasserin Mag.a Phil. Maria Katharina Wiedlack angestrebter akademischer Grad Doktorin der Philosophie (Dr. Phil.) Wien, Jänner 2013 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 092 343 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Anglistik und Amerikanistik Betreuerin / Betreuer: Univ. Prof.in Dr.in Astrid Fellner Earlier versions and parts of chapters One, Two, Three and Six have been published in the peer-reviewed online journal Transposition: the journal 3 (Musique et théorie queer) (2013), as well as in the anthologies Queering Paradigms III ed. by Liz Morrish and Kathleen O’Mara (2013); and Queering Paradigms II ed. by Mathew Ball and Burkard Scherer (2012); * The title “We’re punk as fuck and fuck like punks” is a line from the song Burn your Rainbow by the Canadian queer-feminist punk band the Skinjobs on their 2003 album with the same name (released by Agitprop Records). Content 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................... 1 2. “To Sir With Hate:” A Liminal History of Queer-Feminist Punk Rock ….………………………..…… 21 3. “We’re punk as fuck and fuck like punks:” Punk Rock, Queerness, and the Death Drive ………………………….………….. 69 4. “Challenge the System and Challenge Yourself:” Queer-Feminist Punk Rock’s Intersectional Politics and Anarchism……...……… 119 5. “There’s a Dyke in the Pit:” The Feminist Politics of Queer-Feminist Punk Rock……………..…………….. 157 6. “A Race Riot Did Happen!:” Queer Punks of Color Raising Their Voices ..……………..………… ………….. 207 7. “WE R LA FUCKEN RAZA SO DON’T EVEN FUCKEN DARE:” Anger, and the Politics of Jouissance ……….………………………….…………. -

Eminem 1 Eminem

Eminem 1 Eminem Eminem Eminem performing live at the DJ Hero Party in Los Angeles, June 1, 2009 Background information Birth name Marshall Bruce Mathers III Born October 17, 1972 Saint Joseph, Missouri, U.S. Origin Warren, Michigan, U.S. Genres Hip hop Occupations Rapper Record producer Actor Songwriter Years active 1995–present Labels Interscope, Aftermath Associated acts Dr. Dre, D12, Royce da 5'9", 50 Cent, Obie Trice Website [www.eminem.com www.eminem.com] Marshall Bruce Mathers III (born October 17, 1972),[1] better known by his stage name Eminem, is an American rapper, record producer, and actor. Eminem quickly gained popularity in 1999 with his major-label debut album, The Slim Shady LP, which won a Grammy Award for Best Rap Album. The following album, The Marshall Mathers LP, became the fastest-selling solo album in United States history.[2] It brought Eminem increased popularity, including his own record label, Shady Records, and brought his group project, D12, to mainstream recognition. The Marshall Mathers LP and his third album, The Eminem Show, also won Grammy Awards, making Eminem the first artist to win Best Rap Album for three consecutive LPs. He then won the award again in 2010 for his album Relapse and in 2011 for his album Recovery, giving him a total of 13 Grammys in his career. In 2003, he won the Academy Award for Best Original Song for "Lose Yourself" from the film, 8 Mile, in which he also played the lead. "Lose Yourself" would go on to become the longest running No. 1 hip hop single.[3] Eminem then went on hiatus after touring in 2005. -

The Cauldron 2015

Mikaela Liotta, Cake Head Man, mixed media The Cauldron Senior Editors Grace Jaewon Yoo Muriel Leung Liam Nadire Staff Pann Boonbaichaiyapruck Phoebe Danaher Daniel Fung 2015 Sally Jee Prim Sirisuwannatash Angela Wong Melissa Yukseloglu Faculty Advisor Joseph McDonough 1 Poetry Emma Woodberry Remember 5 GyuHui Hwang Two Buttons Undone 6 Khanh Nyguen I Wait for You to Have Dinner 8 Angela Wong Euphoria 9 Sabi Benedicto The House was Supposed to be Tan 12 (But was Accidentally Painted Yellow) Canvas Li Haze 15 Adam Jolly Spruce and Hemlock Placed By 44 Gentle Hands Jordan Moller The Burning Cold 17 Grace Jaewon Yoo May 18 Silent Hills 40 Lindsay Wallace Forgotten 27 Joelle Troiano Flicker 30 Jack Bilbrough Untitled 31 Valentina Mathis A Hop Skip 32 Jessica Li The Passenger 36 Daddy’s Girl 43 Eugenia Rose stumps 38 Brandon Fong Ironing 47 Ryder Sammons Mixed Media, Ceramics New Year’s Cold 48 Mikaela Liotta Shayla Lamb Spine 7 Senior Year 50 Mermaid 46 Teddy Simson Elephant Skull 16 Prose Eye of the Tiger 53 Muriel Leung Katie I A Great River 20 Imagination 19 Zorte 52 Sabi Benedicto Geniophobia 32 2 Photography Rachel Choe More Please 8 Pann Boonbaichaiyapruck DEAD 2 Spin 12 Swimmingtotheschor 22 Bigfernfloating 41 Lydia Stenflo LA as seen from the 14 Griffith Observatory at Night in March Beach Warrior 58 Meimi Zhu Reflection 30 Jessica Li Juvenescence 37 The Last Door 42 Brandon Fong The End is Neigh 38 Sunday in Menemsha 53 Liam Nadire Hurricane Sandy #22 47 Pride 58 Painting, Drawing Katie I Risen 4 Oban Galbraith The Divide 9 Joni Leung -

Death, Difference, and Dialogue

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 1-1-2009 April 4, 1968: Death, Difference, and Dialogue Kristine Marie Warrenburg University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Warrenburg, Kristine Marie, "April 4, 1968: Death, Difference, and Dialogue" (2009). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 950. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/950 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. APRIL 4, 1968: DEATH, DIFFERENCE, AND DIALOGUE ROBERT F. KENNEDY ANNOUNCES THE ASSASSINATION OF MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR. __________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of Arts and Humanities University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________ by Kristine Warrenburg August 2009 Advisor: Darrin Hicks, Ph.D. ©Copyright by Kristine Warrenburg 2009 All Rights Reserved Author: Kristine Warrenburg Title: APRIL 4, 1968: DEATH, DIFFERENCE, AND DIALOGUE ROBERT F. KENNEDY ANNOUNCES THE ASSASSINATION OF MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR. Advisor: Darrin Hicks, Ph.D. Degree Date: August 2009 ABSTRACT Robert Kennedy’s announcement of the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., in an Indianapolis urban community that did not revolt in riots on April 4, 1968, provides one significant example in which feelings, energy, and bodily risk resonate alongside the articulated message. The relentless focus on Kennedy’s spoken words, in historical biographies and other critical research, presents a problem of isolated effect because the power really comes from elements outside the speech act. -

Most Requested Songs of 2009

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on nearly 2 million requests made at weddings & parties through the DJ Intelligence music request system in 2009 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 2 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 3 Lady Gaga Feat. Colby O'donis Just Dance 4 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 5 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 6 Morrison, Van Brown Eyed Girl 7 Beyonce Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) 8 Timberlake, Justin Sexyback 9 B-52's Love Shack 10 Lynyrd Skynyrd Sweet Home Alabama 11 ABBA Dancing Queen 12 Diamond, Neil Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 13 Black Eyed Peas Boom Boom Pow 14 Rihanna Don't Stop The Music 15 Jackson, Michael Billie Jean 16 Outkast Hey Ya! 17 Sister Sledge We Are Family 18 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 19 Kool & The Gang Celebration 20 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 21 Clapton, Eric Wonderful Tonight 22 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 23 Lady Gaga Poker Face 24 Beatles Twist And Shout 25 James, Etta At Last 26 Black Eyed Peas Let's Get It Started 27 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 28 Jackson, Michael Thriller 29 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 30 Mraz, Jason I'm Yours 31 Commodores Brick House 32 Brooks, Garth Friends In Low Places 33 Temptations My Girl 34 Foundations Build Me Up Buttercup 35 Vanilla Ice Ice Ice Baby 36 Bee Gees Stayin' Alive 37 Sinatra, Frank The Way You Look Tonight 38 Village People Y.M.C.A. -

Rock Music and Representation: the Roles of Rock Culture AMS 311S // Unique No

Page 1 Rock Music and Representation: The Roles of Rock Culture AMS 311s // Unique No. 31080 Spring 2020 BUR 436A: M/W/F 11:00 am – 12:00 pm Instructor: Kate Grover // [email protected] // pronouns: she, her, hers Office Hours: BUR 408 // Monday & Wednesday, 1 pm – 2:30 pm, or by appointment Course Description What is a guitar god? Who gets to be one, and why? What are the “roles” of rock music and culture? What is rock, anyway? This is not your average rock history course. Instead, this course positions 20th and 21st century American rock music and culture as a crucial site for ongoing struggles over identity, belonging, and power. We will explore how race, class, gender, sexuality, age, and ability have shaped how various groups of people engage with rock and what insights these engagements provide about “the American experience” over time. How do rock artists, critics, filmmakers, and fans represent themselves and others? What do these representational strategies reveal about inclusion and exclusion in rock culture, and in American society at large? While examining rock’s players, we will also consider the roles of different rock media and institutions such as MTV, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and Rolling Stone magazine. As such, our course is divided into three units exploring different areas of representation within rock music and culture. Unit 1: Performing Rock, Performing Identity, provides an introduction to studying rock’s sounds, visuals, and texts by investigating various issues of identity within rock music and culture. Unit 2: Evaluating Rock: Writers, Critics, and Other Commentators focuses on the roles of rock critics and the stakes of writing about music. -

EASTSIDE PUNKS a Screening and Conversation Thursday, April 22, 2021, at 7 P.M

THEMEGUIDE EASTSIDE PUNKS A Screening and Conversation Thursday, April 22, 2021, at 7 p.m. Live via Zoom University of Southern California WHAT TO KNOW o Eastside Punks is a series of documentary shorts produced by Razorcake magazine about the first generation of East L.A. punk, circa the late 1970s and early ’80s o This event includes excerpts from Eastside Punks and a panel discussion with members of several of the featured bands: Thee Undertakers, The Brat, and the Stains o Razorcake is an L.A.-based DIY punk zine Photo: Angie Garcia ABOUT THE PARTICIPANTS Jimmy Alvarado (Eastside Punks director) has been active in East L.A.’s underground music scene since 1981 as a musician, backyard gig promoter, writer, poet, bouncer, flyer artist, photographer, podcaster, historian, and filmmaker. He has authored numerous interviews, articles, and short films spotlighting the Eastside scene. He plays guitar in the bands La Tuya and Our Band Sucks. Teresa Covarrubias was the vocalist for The Brat. Their debut EP, Attitudes, was released on The Plugz’ record label, featured contributions from John Doe and Exene from X, and is a prized item among collectors. Straight Outta East L.A., a double Photo: Edward Colver album packaging it with other rare tracks, was released in 2017. Tracy “Skull” Garcia was the bass player of Thee Undertakers. Starting off by playing local parties in 1977, they became regulars in the scene centered around the Vex. Their 1981 debut album, Crucify Me, successfully melded second-wave hardcore bite with first-wave art sensibilities, but wasn’t released until 2001 on CD and 2020 on vinyl.