Death, Difference, and Dialogue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grunge Is Dead Is an Oral History in the Tradition of Please Kill Me, the Seminal History of Punk

THE ORAL SEATTLE ROCK MUSIC HISTORY OF GREG PRATO WEAVING TOGETHER THE DEFINITIVE STORY OF THE SEATTLE MUSIC SCENE IN THE WORDS OF THE PEOPLE WHO WERE THERE, GRUNGE IS DEAD IS AN ORAL HISTORY IN THE TRADITION OF PLEASE KILL ME, THE SEMINAL HISTORY OF PUNK. WITH THE INSIGHT OF MORE THAN 130 OF GRUNGE’S BIGGEST NAMES, GREG PRATO PRESENTS THE ULTIMATE INSIDER’S GUIDE TO A SOUND THAT CHANGED MUSIC FOREVER. THE GRUNGE MOVEMENT MAY HAVE THRIVED FOR ONLY A FEW YEARS, BUT IT SPAWNED SOME OF THE GREATEST ROCK BANDS OF ALL TIME: PEARL JAM, NIRVANA, ALICE IN CHAINS, AND SOUNDGARDEN. GRUNGE IS DEAD FEATURES THE FIRST-EVER INTERVIEW IN WHICH PEARL JAM’S EDDIE VEDDER WAS WILLING TO DISCUSS THE GROUP’S HISTORY IN GREAT DETAIL; ALICE IN CHAINS’ BAND MEMBERS AND LAYNE STALEY’S MOM ON STALEY’S DRUG ADDICTION AND DEATH; INSIGHTS INTO THE RIOT GRRRL MOVEMENT AND OFT-OVERLOOKED BUT HIGHLY INFLUENTIAL SEATTLE BANDS LIKE MOTHER LOVE BONE, THE MELVINS, SCREAMING TREES, AND MUDHONEY; AND MUCH MORE. GRUNGE IS DEAD DIGS DEEP, STARTING IN THE EARLY ’60S, TO EXPLAIN THE CHAIN OF EVENTS THAT GAVE WAY TO THE MUSIC. THE END RESULT IS A BOOK THAT INCLUDES A WEALTH OF PREVIOUSLY UNTOLD STORIES AND FRESH INSIGHT FOR THE LONGTIME FAN, AS WELL AS THE ESSENTIALS AND HIGHLIGHTS FOR THE NEWCOMER — THE WHOLE UNCENSORED TRUTH — IN ONE COMPREHENSIVE VOLUME. GREG PRATO IS A LONG ISLAND, NEW YORK-BASED WRITER, WHO REGULARLY WRITES FOR ALL MUSIC GUIDE, BILLBOARD.COM, ROLLING STONE.COM, RECORD COLLECTOR MAGAZINE, AND CLASSIC ROCK MAGAZINE. -

The Cauldron 2015

Mikaela Liotta, Cake Head Man, mixed media The Cauldron Senior Editors Grace Jaewon Yoo Muriel Leung Liam Nadire Staff Pann Boonbaichaiyapruck Phoebe Danaher Daniel Fung 2015 Sally Jee Prim Sirisuwannatash Angela Wong Melissa Yukseloglu Faculty Advisor Joseph McDonough 1 Poetry Emma Woodberry Remember 5 GyuHui Hwang Two Buttons Undone 6 Khanh Nyguen I Wait for You to Have Dinner 8 Angela Wong Euphoria 9 Sabi Benedicto The House was Supposed to be Tan 12 (But was Accidentally Painted Yellow) Canvas Li Haze 15 Adam Jolly Spruce and Hemlock Placed By 44 Gentle Hands Jordan Moller The Burning Cold 17 Grace Jaewon Yoo May 18 Silent Hills 40 Lindsay Wallace Forgotten 27 Joelle Troiano Flicker 30 Jack Bilbrough Untitled 31 Valentina Mathis A Hop Skip 32 Jessica Li The Passenger 36 Daddy’s Girl 43 Eugenia Rose stumps 38 Brandon Fong Ironing 47 Ryder Sammons Mixed Media, Ceramics New Year’s Cold 48 Mikaela Liotta Shayla Lamb Spine 7 Senior Year 50 Mermaid 46 Teddy Simson Elephant Skull 16 Prose Eye of the Tiger 53 Muriel Leung Katie I A Great River 20 Imagination 19 Zorte 52 Sabi Benedicto Geniophobia 32 2 Photography Rachel Choe More Please 8 Pann Boonbaichaiyapruck DEAD 2 Spin 12 Swimmingtotheschor 22 Bigfernfloating 41 Lydia Stenflo LA as seen from the 14 Griffith Observatory at Night in March Beach Warrior 58 Meimi Zhu Reflection 30 Jessica Li Juvenescence 37 The Last Door 42 Brandon Fong The End is Neigh 38 Sunday in Menemsha 53 Liam Nadire Hurricane Sandy #22 47 Pride 58 Painting, Drawing Katie I Risen 4 Oban Galbraith The Divide 9 Joni Leung -

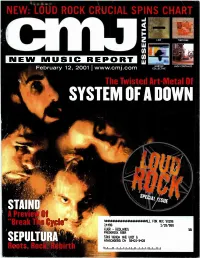

System of a Down Molds Metal Like Silly Putty, Bending and Shaping Its Parame- 12 Slayer's First Amendment Ters to Fit the Band's Twisted Vision

NEW: LOUD ROCK CRUCIAL SPINS CHART LOW TORTOISE 1111 NEW MUSIC REPORT Uà NORTEC JACK COSTANZO February 12, 20011 www.cmj.com COLLECTIVE The Twisted Art-Metal Of SYSTEM OF ADOWN 444****************444WALL FOR ADC 90138 24438 2/28/388 KUOR - REDLAHDS FREDERICK SUER S2V3HOD AUE unr G ATASCADER0 CA 88422-3428 IIii II i ti iii it iii titi, III IlitlIlli lilt ti It III ti ER THEIR SELF TITLED DEBUT AT RADIO NOW • FOR COLLEGE CONTACT PHIL KASO: [email protected] 212-274-7544 FOR METAL CONTACT JEN MEULA: [email protected] 212-274-7545 Management: Bryan Coleman for Union Entertainment Produced & Mixed by Bob Marlette Production & Engineering of bass and drum tracks by Bill Kennedy a OADRUNNEll ACME MCCOWN« ROADRUNNER www.downermusic.com www.roadrunnerrecords.com 0 2001 Roadrunner Records. Inc. " " " • Issue 701 • Vol 66 • No 7 FEATURES 8 Bucking The System member, the band is out to prove it still has Citing Jane's Addiction as a primary influ- the juice with its new release, Nation. ence, System Of A Down molds metal like Silly Putty, bending and shaping its parame- 12 Slayer's First Amendment ters to fit the band's twisted vision. Loud Follies Rock Editor Amy Sciarretto taps SOAD for Free speech is fodder for the courts once the scoop on its upcoming summer release. again. This time the principals involved are a headbanger institution and the parents of 10 It Takes A Nation daughter who was brutally murdered by three Some question whether Sepultura will ever of its supposed fans. be same without larger-than-life frontman 15 CM/A: Staincl Max Cavalera. -

GREEN, GREEN, & TENDER a Thesis Submitted to Kent State University

GREEN, GREEN, & TENDER A thesis submitted To Kent State University in partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts by Karly R. Milvet May, 2016 © Copyright All rights reserved Except for previously published materials Green, Green, & Tender written by Karly R. Milvet B.A., Kent State University, 2012 M.F.A., Kent State University, 2016 Approved by Catherine Wing , Advisor Robert Trogdon , Chair, Department of English James L. Blank , Dean, College of Arts and Science Table of Contents Part I Midnight, Tiny Tokyo..................................................................................................................... 2 Coming Over................................................................................................................................... 3 Someday Knowing.......................................................................................................................... 4 Advice I Should Have Taken.......................................................................................................... 6 [ ] .......................................................................................................................................... 7 Dear Anna....................................................................................................................................... 8 A Story of Origins......................................................................................................................... 10 A Poem Is the Threat Of What We’re -

Solo Works JAPAN

Solo Works JAPAN David Gilmour David Gilmour Sampler David Gilmour Guest Appearances David Gilmour Promotional Issues Roger Waters Roger Waters Sampler Roger Waters Soundtrack Roger Waters Promotional Issues PINK FLOYD DVD DISCOGRAPHY Copyright © 2003-2011 Hans Gerlitz. All rights reserved. www.pinkfloyd-forum.de/discography [email protected] This discography is a reference guide, not a book on the artwork of Pink Floyd. The photos of the artworks are used solely for the purposes of distinguishing the differences between the releases. The product names used in this document are for identification purposes only. All trademarks and registered trademarks are the property of their respective owners. Permission is granted to download and print this document for personal use. Any other use including but not limited to commercial or profitable purposes or uploading to any publicly accessibly web site is expressly forbidden without prior written consent of the author. JAPAN PINK FLOYD DVD DISCOGRAPHY PINK FLOYD DVD DISCOGRAPHY Solo Works JAPAN David Gilmour David Gilmour in Concert Label: Capitol Catalog numbers: TOBW-3059 4 988006 942912 (barcode) Country of origin: Japan Format : 16:9 Notes: Concert film from 2002 with guest appearance of Richard Wright. Issued in a standard Amaray case. David Gilmour in Concert Label: Capitol Catalog numbers: TOBW-92008 4 988006 946255 (barcode) Country of origin: Japan Format : 16:9 Notes: Concert film from 2002 with guest appearance of Richard Wright. Issued in a standard Amaray case. JAPAN PINK FLOYD DVD DISCOGRAPHY On An Island – Limited Edition CD + DVD Label: Sony Catalog numbers: MHCP 1223-4 (on OBI spine) MHCP 1223-4 (on rear of OBI) 4 582192 932636 (barcode on OBI) 8 2876-80280-2 5 (barcode on rear of the CD cover) MHCP 1223-4 (on rear of the CD cover) MHCP 1223 (on CD) no barcode on rear of the DVD cover MHCP 1223-4 (on rear of the DVD cover) MHCP 1224 (on DVD) Country of origin: Japan Notes: Limited edition which includes the regular CD and the “Live And In Session” DVD. -

Solo Works USA

Solo Works USA Syd Barrett David Gilmour David Gilmour Sampler David Gilmour Soundtrack David Gilmour Guest Appearances David Gilmour Promotional Issues Roger Waters Roger Waters Sampler Roger Waters Soundtrack Roger Waters Promotional Issues PINK FLOYD DVD DISCOGRAPHY Copyright © 2003-2011 Hans Gerlitz. All rights reserved. www.pinkfloyd-forum.de/discography [email protected] This discography is a reference guide, not a book on the artwork of Pink Floyd. The photos of the artworks are used solely for the purposes of distinguishing the differences between the releases. The product names used in this document are for identification purposes only. All trademarks and registered trademarks are the property of their respective owners. Permission is granted to download and print this document for personal use. Any other use including but not limited to commercial or profitable purposes or uploading to any publicly accessibly web site is expressly forbidden without prior written consent of the author. USA PINK FLOYD DVD DISCOGRAPHY PINK FLOYD DVD DISCOGRAPHY Solo Works USA Syd Barrett Syd Barrett's First Trip Label: MVD Music Video Catalog number: DR-2780 (on case spine) 0 22891 27802 3 (barcode on rear cover) Release Date: 2001 Country of origin: USA Format : 4:3 Language: English Subtitles: none Notes: “ Limited edition” home movie recordings from the early days of Barrett and Pink Floyd showing Syd taking mushrooms - and the band after signing their first contract. USA PINK FLOYD DVD DISCOGRAPHY PINK FLOYD DVD DISCOGRAPHY Solo Works USA David Gilmour David Gilmour In Concert Label: Capitol Records Catalog number: C9 7243 4 92960 9 1 (on case spine) 7 24349 29609 1 (barcode on rear cover) Release Date: November 5, 2002 Country of origin: USA Format : 16:9 Language: English Extras: Spare Digits, Home Movie, High Hopes choral and some rare recordings (I Put a Spell on You, Don’t, Sonnet 18) Notes: Concert film from 2002 with guest appearance of Richard Wright. -

A Collection of Short Stories Scott Randall a Creative Writing Project

LEARNED HELPLESSNESS a collection of short stories by Scott Randall A Creative Writing Project submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research through English Language, Literature and Creative Writing in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts at the University of Windsor Windsor, Ontario, Canada 1998 Copyright 1998 Scott Randall National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1+1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellington Ottawa ON K 1A ON4 OrtawaON K1AON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or seii reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Acknowledgments 1 am grateful to Dr. John Ditsky and Dr. Alistair MacLeod for their tirne, their writing, and their warm, generous hearts. Thank you. for Sharon Anne and Katrina Ernber Contents First Impressions ........................................... -1 Two Ends of Time Are Neatïy Tied ............................ -

Elements 2019 Edition

King of the World I Am – Eric Short – Visual – 2019 Elements 2019 Editor-in-Chief: Morgan Cusack Faculty Advisor: Dr. Erika T. Wurth Editorial Board: Christian Sessom, Isai Lopez, Emma Dayhoff, Morgan Cusack and Jacob Taylor Alexis Fioroni Connor Sullivan Fairy Tales Evil Crow Unlocked Jewel Woodward everything isn’t what it always seems Angelique Herrera Abandonment Cory Clark Just a Bite Broken Memory In the Dust Kate Birr Caught Austin Middelton Days Gone Sidney Bottino Coffee Curtis Pointer Sound Casey Hendrickson Ekpharastic Cold Human Aaron Mendenall This Evening Jacob Taylor Don’t Blame Your Diagnosis Living in Chicago Kaylee Gundling Emma Dayhoff Meshes of the Afternoon Greenwood Letting Go Director’s Cut Joshua Miller No Longer Alone Morgan Cusack this place you made Matt Barry Chasing the Sun Birdcage Those Left Behind Shelby Davin Emilie Hahn The Boogeyman Overcome: A Sestina Marshelle Kellum Emily Trenter Me a Writer? Frozen Patience Alisa Davis Deadbeat Dads Best Part Winners of the Lois C. Bruner Creative Nonfiction Award: 1st Place - Marissa Purdum The Dog Days 2nd Place - Marcus Sweeten A Dose of Change 3rd Place - Kendrick Keller Flight Winners of the Cordell Larner Award in Fiction: 1st Place - Adam Norris Cheap Rubber Mulch 2nd Place - Angelique Herrera Hush Hush 3rd Place - Brandon Williams End Measured Mile Winners of the Cordell Larner Award in Poetry: 1st Place - Eric Short Speak to us on Freedom The Drinking Game You’re Old Country Now 2nd Place - Marcus Sweeten 102 E. Clay Zerzan 3rd Place - Janae Imeri The Puppeteer and The Puppet Train of Thought Alexis Fioroni “Fairy Tales” What did you do? I did what any woman would do, I filled my bed with the finest queens Searching for you, in their damp skin I kissed the quiet valleys in the cracks of their backs, their celestial mooans, Danced with sacred fairies. -

Þáttur 6.Odt

Obscured by Clouds When You're in Good afternoon. My name is Björgvin Rúnar Leifsson and this is an episode about Pink Floyd. Although a certain foundation for "Dark Side of the Moon" had already been laid out in early 1972, it still took the band most of the year to develop the music and, among other things, test it on the audience at several concerts during that year. One of the reasons why Dark Side took so long to emerge is because they suffered some distractions as Mason puts it in his book. To start with the latter, the film "Live at Pompei" about the eponymous, Pink Floyd's spectator-free concert in the ancient city of Pompeii was released in November 1972, although the concert had taken place more than a year earlier. Then, in early 1972 they took some time to record film music for another film by Barbet Schroeder, the same person who made More in 1969. The film is called La Vallee and is about a woman who goes on a strange self-guided tour in Papua New Guinea's jungles and among other things, meets the Mapuga tribe, who are propably the most isolated people on earth. The film was released on July 11, 1972, just over a month after the release of the album and got the subtitle "Obscured by Clouds" which was the name that Pink Floyd decided to give the album after a heated argument with the film company. All the music on Obscured by Clouds was composed and recorded over several days in February and March 1972. -

Adele Live at the Royal Albert Hall Mkv 1080P Dts

1 / 2 Adele Live At The Royal Albert Hall Mkv 1080p Dts name, se, le, time, size info, uploader. Adele Live at the Royal Albert Hall (2011) (1080p BluRay x265 HEVC 10bit AAC 5.1 Tigole) [QxR]5, 43, 9, Jul.. Iron Man 2 2010 2160p GER UHD BluRay HDR HEVC DTS-HD MA 5. ... 1 MPEG2-TrollHD Adele: Live at the Royal Albert Hall (2011) AVC 1080I DTS HDMA 5.. Pink Floyd Classics Live in Concert @1080p HDTV HD Widescreen Pinkfloyd, ... Concert Pulse (1994) Adele Live At The. Royal Albert Hall Mkv 1080p Dts.mkv.. 阿黛尔伦敦爱尔伯特音乐厅演唱会Adele Live at the Royal Albert Hall》是2011年由 ... Adele.Live.at.the.Royal.Albert.Hall.2011.BluRay.1080p.DTS.x264-CHD[8.58 GB] .... 3 мар. 2015 г. — Adele - Live at The Royal Albert Hall (2011) 1 CD | Tracks: 17 | Flac, Tracks+.cue | Genre: Pop, Soul, RnB Size: 469 mb | Front, Back, .... Download Free PC Software with their Crack, Patch, Keygen, Serial key, License keys, Product keys, . ... Adele Live At The Royal Albert Hall Mkv 1080p Dts.. 版本:1080p BluRay DTS x264 mkv. 格式: Subrip(srt) 语言:简(?) 字幕文件名:[Adele Live At the Royal Albert Hall] 1080p BluRay... 日期: 2014-12-06 05:14:46.. Find Adele - Live at the Royal Albert Hall (+ Audio-CD) [2 DVDs] at ... The DTS-HD Master soundtrack is great if the have the supporting equipment to decode .... DTS.x264-HDMaNiAcS Adele-Live at the Royal Albert Hall 2011 720p Alanis. ... HDTV.720p.x264-pia Placebo We Come In Pieces Mkv 1080p Dts Hd Red.Hot.Chilli.. Live At The Royal Albert Hall was recorded on September 22 at the height of what has been an amazing year for Adele. -

Clas of 2026 Woul Lik T Dedicat Thi Volum T Mr . Kath Curt

�� Clas� of 2026 woul� lik� t� dedicat� thi� volum� t� Mr�. Kath� Curt� W� than� Mr�. Curt� for helpin� u� t� paus� an� reflec� o� our strength�, joy�, an� struggle� aer suc� � demandin� year. W� hav� ha� t� adap� t� man� challenge� durin� thi� pandemi�, bu� reconnectin� wit� our value� an� eachother help� t� keep u� grounde� an� ope� t� findin� new meaning�. I� Gratitud�, Mr�. Daniell� Pec� an� M�. Perron�’� Sevent� Grad� Clas� Jun� 2021 1 I Believe in the Power of Music By: Carly Suessenbach I believe in the power of music. Music can help people in so many ways like when you are sad you can listen to happy music, if you can't sleep you can turn on calming music that doesn't have any lyrics, or you can put on sad music if you just want to let out a cry. Music can also motivate you or inspire you to do something. Music helps me by calming me down when I'm stressed, makes me happy when I am sad or angry, or sometimes I just listen to sad music because I just feel like it. Music also helps me fall asleep faster. When I listen to music I feel like I'm in a whole different world and in that world all my worries, problems and stress goes away and I feel happy. Music is important to me because a lot of songs have really deep meanings to them. Music inspires me to make my own music or learn to play the piano or guitar. -

Page | 1 Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA

Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. JACKIE MCLEAN NEA Jazz Master (2001) Interviewee: Jackie McLean (May 17, 1931 – March 31, 2006) Interviewer: William Brower with recording engineer Sven Abow Date: July 20-21, 2001 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History. Smithsonian Institution Description: Transcript, 131 pp. Brower: My name is William Brower. I’m sitting with Jackie McLean at the Artists Collective in Hartford, Connecticut, on Friday, July the 20th, 2001. We’re conducting an oral history interview for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Project. The first thing I’d like to do is thank Mr. McLean for agreeing to participate in this oral history. McLean: Oh, it’s my pleasure. It’s very important. Brower: I want to start with what we were talking about before we actually started the formal interview and ask you to tell us about your recent trip to Europe, where you played, with whom you were playing, and then talk about how you’re handling your performance – the performance dimension of your life – right now. McLean: This most recent trip that I made – I made two trips to play with Mal Waldron. The first one was in Verona, Italy, a couple of weeks ago. That was a duo where Mal and I played for about 70 minutes solo, between he and I, duo. Then I went just last week over to the North Sea Festival in the Hague to play with Mal again, this time with his trio, with Andrew Cyrille, Reggie Workman, Mal, and I was special guest.