Forest History Oral History Project Minnesota Historical Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grunge Is Dead Is an Oral History in the Tradition of Please Kill Me, the Seminal History of Punk

THE ORAL SEATTLE ROCK MUSIC HISTORY OF GREG PRATO WEAVING TOGETHER THE DEFINITIVE STORY OF THE SEATTLE MUSIC SCENE IN THE WORDS OF THE PEOPLE WHO WERE THERE, GRUNGE IS DEAD IS AN ORAL HISTORY IN THE TRADITION OF PLEASE KILL ME, THE SEMINAL HISTORY OF PUNK. WITH THE INSIGHT OF MORE THAN 130 OF GRUNGE’S BIGGEST NAMES, GREG PRATO PRESENTS THE ULTIMATE INSIDER’S GUIDE TO A SOUND THAT CHANGED MUSIC FOREVER. THE GRUNGE MOVEMENT MAY HAVE THRIVED FOR ONLY A FEW YEARS, BUT IT SPAWNED SOME OF THE GREATEST ROCK BANDS OF ALL TIME: PEARL JAM, NIRVANA, ALICE IN CHAINS, AND SOUNDGARDEN. GRUNGE IS DEAD FEATURES THE FIRST-EVER INTERVIEW IN WHICH PEARL JAM’S EDDIE VEDDER WAS WILLING TO DISCUSS THE GROUP’S HISTORY IN GREAT DETAIL; ALICE IN CHAINS’ BAND MEMBERS AND LAYNE STALEY’S MOM ON STALEY’S DRUG ADDICTION AND DEATH; INSIGHTS INTO THE RIOT GRRRL MOVEMENT AND OFT-OVERLOOKED BUT HIGHLY INFLUENTIAL SEATTLE BANDS LIKE MOTHER LOVE BONE, THE MELVINS, SCREAMING TREES, AND MUDHONEY; AND MUCH MORE. GRUNGE IS DEAD DIGS DEEP, STARTING IN THE EARLY ’60S, TO EXPLAIN THE CHAIN OF EVENTS THAT GAVE WAY TO THE MUSIC. THE END RESULT IS A BOOK THAT INCLUDES A WEALTH OF PREVIOUSLY UNTOLD STORIES AND FRESH INSIGHT FOR THE LONGTIME FAN, AS WELL AS THE ESSENTIALS AND HIGHLIGHTS FOR THE NEWCOMER — THE WHOLE UNCENSORED TRUTH — IN ONE COMPREHENSIVE VOLUME. GREG PRATO IS A LONG ISLAND, NEW YORK-BASED WRITER, WHO REGULARLY WRITES FOR ALL MUSIC GUIDE, BILLBOARD.COM, ROLLING STONE.COM, RECORD COLLECTOR MAGAZINE, AND CLASSIC ROCK MAGAZINE. -

Sew Any Fabric Provides Practical, Clear Information for Novices and Inspiration for More Experienced Sewers Who Are Looking for New Ideas and Techniques

SAFBCOV.qxd 10/23/03 3:34 PM Page 1 S Fabric Basics at Your Fingertips EW A ave you ever wished you could call an expert and ask for a five-minute explanation on the particulars of a fabric you are sewing? Claire Shaeffer provides this key information for 88 of today’s most NY SEW ANY popular fabrics. In this handy, easy-to-follow reference, she guides you through all the basics while providing hints, tips, and suggestions based on her 20-plus years as a college instructor, pattern F designer, and author. ABRIC H In each concise chapter, Claire shares fabric facts, design ideas, workroom secrets, and her sewing checklist, as well as her sewability classification to advise you on the difficulty of sewing each ABRIC fabric. Color photographs offer further ideas. The succeeding sections offer sewing techniques and ForewordForeword byby advice on needles, threads, stabilizers, and interfacings. Claire’s unique fabric/fiber dictionary cross- NancyNancy ZiemanZieman references over 600 additional fabrics. An invaluable reference for anyone who F sews, Sew Any Fabric provides practical, clear information for novices and inspiration for more experienced sewers who are looking for new ideas and techniques. About the Author Shaeffer Claire Shaeffer is a well-known and well- respected designer, teacher, and author of 15 books, including Claire Shaeffer’s Fabric Sewing Guide. She has traveled the world over sharing her sewing secrets with novice, experienced, and professional sewers alike. Claire was recently awarded the prestigious Lifetime Achievement Award by the Professional Association of Custom Clothiers (PACC). Claire and her husband reside in Palm Springs, California. -

Storenewsoflansburgh&Brq

nr J TIMES. THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 6, 1919. 7 THE WASHINGTON - , mmm - - ... -JJ SOLONS PLAN BUYS AERIAL WAR w. EQUIPMENT W- StoreNewsofLansburgh&Brq. FOR TIFF KB FRiDi- - rr 3. jjmmmmmWWimMs The British embargo on American Two Lob 1 goods and efforts, apparently de Editorial Modes In Fine Spring Suits ; New signed to gobble American trade, will Wash Goods Republl- - An enthusiastic merchant be used by "high rotection" wrote a to his former cans Congress an argument for letter in as office boy who had just got- Remnants . tariff up- Chic Fashions for the Spring Appealing in Silhouette and immediate revision of the 'Mm ten back from France ask- Specially Priced ward. to call and see about Tariff legislation probably will be HIh ing him Exemplary in Tailoring among measures present-- 1 mm his old position. Included in these two lots of the earliest ;lSb JRv in walked ed when the Republicans takft the A few days later high-cla- ss white and col- industry b&mH?- - mm in officer's Suits fresh from the tailors hands. They reins in Congress. American the younjf man These are wash goods are thou- niust be helped over the readjustment i uniform two silver bars on ored Kepuu special collection fashion period and then protected, tne i ' Klfe-JH- his shoulders. represent a that our sands of yards all ia $ood lieann arnm. Tentative drafts of a -' lengths and best qualities. new law already have been assembled for early Not only tariff Both employer and employe salon customers. -- made. ' "confused. They consist of voiles, resumes discus-- , were net a little When the Senate do show the smart new lines and touches poplins, . -

The Cauldron 2015

Mikaela Liotta, Cake Head Man, mixed media The Cauldron Senior Editors Grace Jaewon Yoo Muriel Leung Liam Nadire Staff Pann Boonbaichaiyapruck Phoebe Danaher Daniel Fung 2015 Sally Jee Prim Sirisuwannatash Angela Wong Melissa Yukseloglu Faculty Advisor Joseph McDonough 1 Poetry Emma Woodberry Remember 5 GyuHui Hwang Two Buttons Undone 6 Khanh Nyguen I Wait for You to Have Dinner 8 Angela Wong Euphoria 9 Sabi Benedicto The House was Supposed to be Tan 12 (But was Accidentally Painted Yellow) Canvas Li Haze 15 Adam Jolly Spruce and Hemlock Placed By 44 Gentle Hands Jordan Moller The Burning Cold 17 Grace Jaewon Yoo May 18 Silent Hills 40 Lindsay Wallace Forgotten 27 Joelle Troiano Flicker 30 Jack Bilbrough Untitled 31 Valentina Mathis A Hop Skip 32 Jessica Li The Passenger 36 Daddy’s Girl 43 Eugenia Rose stumps 38 Brandon Fong Ironing 47 Ryder Sammons Mixed Media, Ceramics New Year’s Cold 48 Mikaela Liotta Shayla Lamb Spine 7 Senior Year 50 Mermaid 46 Teddy Simson Elephant Skull 16 Prose Eye of the Tiger 53 Muriel Leung Katie I A Great River 20 Imagination 19 Zorte 52 Sabi Benedicto Geniophobia 32 2 Photography Rachel Choe More Please 8 Pann Boonbaichaiyapruck DEAD 2 Spin 12 Swimmingtotheschor 22 Bigfernfloating 41 Lydia Stenflo LA as seen from the 14 Griffith Observatory at Night in March Beach Warrior 58 Meimi Zhu Reflection 30 Jessica Li Juvenescence 37 The Last Door 42 Brandon Fong The End is Neigh 38 Sunday in Menemsha 53 Liam Nadire Hurricane Sandy #22 47 Pride 58 Painting, Drawing Katie I Risen 4 Oban Galbraith The Divide 9 Joni Leung -

Death, Difference, and Dialogue

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 1-1-2009 April 4, 1968: Death, Difference, and Dialogue Kristine Marie Warrenburg University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Warrenburg, Kristine Marie, "April 4, 1968: Death, Difference, and Dialogue" (2009). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 950. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/950 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. APRIL 4, 1968: DEATH, DIFFERENCE, AND DIALOGUE ROBERT F. KENNEDY ANNOUNCES THE ASSASSINATION OF MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR. __________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of Arts and Humanities University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________ by Kristine Warrenburg August 2009 Advisor: Darrin Hicks, Ph.D. ©Copyright by Kristine Warrenburg 2009 All Rights Reserved Author: Kristine Warrenburg Title: APRIL 4, 1968: DEATH, DIFFERENCE, AND DIALOGUE ROBERT F. KENNEDY ANNOUNCES THE ASSASSINATION OF MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR. Advisor: Darrin Hicks, Ph.D. Degree Date: August 2009 ABSTRACT Robert Kennedy’s announcement of the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., in an Indianapolis urban community that did not revolt in riots on April 4, 1968, provides one significant example in which feelings, energy, and bodily risk resonate alongside the articulated message. The relentless focus on Kennedy’s spoken words, in historical biographies and other critical research, presents a problem of isolated effect because the power really comes from elements outside the speech act. -

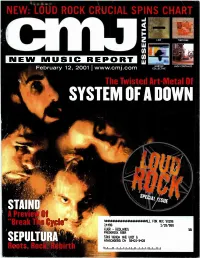

System of a Down Molds Metal Like Silly Putty, Bending and Shaping Its Parame- 12 Slayer's First Amendment Ters to Fit the Band's Twisted Vision

NEW: LOUD ROCK CRUCIAL SPINS CHART LOW TORTOISE 1111 NEW MUSIC REPORT Uà NORTEC JACK COSTANZO February 12, 20011 www.cmj.com COLLECTIVE The Twisted Art-Metal Of SYSTEM OF ADOWN 444****************444WALL FOR ADC 90138 24438 2/28/388 KUOR - REDLAHDS FREDERICK SUER S2V3HOD AUE unr G ATASCADER0 CA 88422-3428 IIii II i ti iii it iii titi, III IlitlIlli lilt ti It III ti ER THEIR SELF TITLED DEBUT AT RADIO NOW • FOR COLLEGE CONTACT PHIL KASO: [email protected] 212-274-7544 FOR METAL CONTACT JEN MEULA: [email protected] 212-274-7545 Management: Bryan Coleman for Union Entertainment Produced & Mixed by Bob Marlette Production & Engineering of bass and drum tracks by Bill Kennedy a OADRUNNEll ACME MCCOWN« ROADRUNNER www.downermusic.com www.roadrunnerrecords.com 0 2001 Roadrunner Records. Inc. " " " • Issue 701 • Vol 66 • No 7 FEATURES 8 Bucking The System member, the band is out to prove it still has Citing Jane's Addiction as a primary influ- the juice with its new release, Nation. ence, System Of A Down molds metal like Silly Putty, bending and shaping its parame- 12 Slayer's First Amendment ters to fit the band's twisted vision. Loud Follies Rock Editor Amy Sciarretto taps SOAD for Free speech is fodder for the courts once the scoop on its upcoming summer release. again. This time the principals involved are a headbanger institution and the parents of 10 It Takes A Nation daughter who was brutally murdered by three Some question whether Sepultura will ever of its supposed fans. be same without larger-than-life frontman 15 CM/A: Staincl Max Cavalera. -

Stylwear Clothes

frmiTiTTWirriiir!K a Bvy.iyg woiifD, fkidaYh yoymjij, 7, im. it ENQINE-ORASrHNJUR- FIVE. JGLQAK MODELHSKS $00,000- - A Wide Variety Virm Truck Goes Through Window of Men's and Young Men's Ur WAK PLANb bNUlNbtH --One Man Will Die. Bench Made Fall and Winter Shoes In Black, Tan and the New Christmas Spectacle Opens With a 7, Great BVltACUSE, N, York's T.. Nov. One man 9ic Charges He Is Now Going to waa fatally Injured and four others new Browns. In Marry Another terlouil) hurt yesterday when an Calf, Kid and auto fire engine crashed through a Woman. Cordovan. big plate glass window nnd Into the Unusual WANAMAKER'S. 1 lobby Saturday, tM.OOO ot Hotel 10.30 Suit to recover for attest the Winchester. The at values. Carnival Parade breech ot promise was brought yeater-6- T driver had tried to avoid colllalon In the 8upremfi Court. Brooklyn. I.v with u twin car. At MUi Marxuertte Frohman, k pretty Both trucks were apeedlng In $9.00. Jack-and-the-Bean-S- World-Ba- cloak model of No. Wl Lincoln ru v. aporise to an alarm uf fire and met up talk and Toy ng! They're Off! against James A. May. engineer. In at rlsht angles In. front of the hotel. oluxre ot the plant ot the Nentor Ma- William Ammurman of Moravia, a nufactory; Company, No. 40 Wet 13th travelling salesman, was hit. Hla Street, Manhattan, which during the skull was fractured and he was In- - war luppllcd airplanes to the dovern ternally hurt. -

GREEN, GREEN, & TENDER a Thesis Submitted to Kent State University

GREEN, GREEN, & TENDER A thesis submitted To Kent State University in partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts by Karly R. Milvet May, 2016 © Copyright All rights reserved Except for previously published materials Green, Green, & Tender written by Karly R. Milvet B.A., Kent State University, 2012 M.F.A., Kent State University, 2016 Approved by Catherine Wing , Advisor Robert Trogdon , Chair, Department of English James L. Blank , Dean, College of Arts and Science Table of Contents Part I Midnight, Tiny Tokyo..................................................................................................................... 2 Coming Over................................................................................................................................... 3 Someday Knowing.......................................................................................................................... 4 Advice I Should Have Taken.......................................................................................................... 6 [ ] .......................................................................................................................................... 7 Dear Anna....................................................................................................................................... 8 A Story of Origins......................................................................................................................... 10 A Poem Is the Threat Of What We’re -

Solo Works JAPAN

Solo Works JAPAN David Gilmour David Gilmour Sampler David Gilmour Guest Appearances David Gilmour Promotional Issues Roger Waters Roger Waters Sampler Roger Waters Soundtrack Roger Waters Promotional Issues PINK FLOYD DVD DISCOGRAPHY Copyright © 2003-2011 Hans Gerlitz. All rights reserved. www.pinkfloyd-forum.de/discography [email protected] This discography is a reference guide, not a book on the artwork of Pink Floyd. The photos of the artworks are used solely for the purposes of distinguishing the differences between the releases. The product names used in this document are for identification purposes only. All trademarks and registered trademarks are the property of their respective owners. Permission is granted to download and print this document for personal use. Any other use including but not limited to commercial or profitable purposes or uploading to any publicly accessibly web site is expressly forbidden without prior written consent of the author. JAPAN PINK FLOYD DVD DISCOGRAPHY PINK FLOYD DVD DISCOGRAPHY Solo Works JAPAN David Gilmour David Gilmour in Concert Label: Capitol Catalog numbers: TOBW-3059 4 988006 942912 (barcode) Country of origin: Japan Format : 16:9 Notes: Concert film from 2002 with guest appearance of Richard Wright. Issued in a standard Amaray case. David Gilmour in Concert Label: Capitol Catalog numbers: TOBW-92008 4 988006 946255 (barcode) Country of origin: Japan Format : 16:9 Notes: Concert film from 2002 with guest appearance of Richard Wright. Issued in a standard Amaray case. JAPAN PINK FLOYD DVD DISCOGRAPHY On An Island – Limited Edition CD + DVD Label: Sony Catalog numbers: MHCP 1223-4 (on OBI spine) MHCP 1223-4 (on rear of OBI) 4 582192 932636 (barcode on OBI) 8 2876-80280-2 5 (barcode on rear of the CD cover) MHCP 1223-4 (on rear of the CD cover) MHCP 1223 (on CD) no barcode on rear of the DVD cover MHCP 1223-4 (on rear of the DVD cover) MHCP 1224 (on DVD) Country of origin: Japan Notes: Limited edition which includes the regular CD and the “Live And In Session” DVD. -

Solo Works USA

Solo Works USA Syd Barrett David Gilmour David Gilmour Sampler David Gilmour Soundtrack David Gilmour Guest Appearances David Gilmour Promotional Issues Roger Waters Roger Waters Sampler Roger Waters Soundtrack Roger Waters Promotional Issues PINK FLOYD DVD DISCOGRAPHY Copyright © 2003-2011 Hans Gerlitz. All rights reserved. www.pinkfloyd-forum.de/discography [email protected] This discography is a reference guide, not a book on the artwork of Pink Floyd. The photos of the artworks are used solely for the purposes of distinguishing the differences between the releases. The product names used in this document are for identification purposes only. All trademarks and registered trademarks are the property of their respective owners. Permission is granted to download and print this document for personal use. Any other use including but not limited to commercial or profitable purposes or uploading to any publicly accessibly web site is expressly forbidden without prior written consent of the author. USA PINK FLOYD DVD DISCOGRAPHY PINK FLOYD DVD DISCOGRAPHY Solo Works USA Syd Barrett Syd Barrett's First Trip Label: MVD Music Video Catalog number: DR-2780 (on case spine) 0 22891 27802 3 (barcode on rear cover) Release Date: 2001 Country of origin: USA Format : 4:3 Language: English Subtitles: none Notes: “ Limited edition” home movie recordings from the early days of Barrett and Pink Floyd showing Syd taking mushrooms - and the band after signing their first contract. USA PINK FLOYD DVD DISCOGRAPHY PINK FLOYD DVD DISCOGRAPHY Solo Works USA David Gilmour David Gilmour In Concert Label: Capitol Records Catalog number: C9 7243 4 92960 9 1 (on case spine) 7 24349 29609 1 (barcode on rear cover) Release Date: November 5, 2002 Country of origin: USA Format : 16:9 Language: English Extras: Spare Digits, Home Movie, High Hopes choral and some rare recordings (I Put a Spell on You, Don’t, Sonnet 18) Notes: Concert film from 2002 with guest appearance of Richard Wright. -

THE FAIR Anniversary at (Main Floor)

FRIDAY. NOV. 23. 1923 THE INDIANAPOLIS TIMES 3 Store Open Saturdays Till 9 P. M. BAGS—PURSES Children’s Novelty Anniversary Sale of “The Store of Greater Values” Girls’ Wool $2.00 BROCADED 18th Anniversary Sale of Corselettes To $2 Boxes 75c HAND BAGS BRASSIERES Gauntlet Gloves CORSETS SI.OO and Vanity Cases Which are so popular this Two pair supporters, flesh Large Just unpacked, pouch shapes, Flesh color, basket FLESH color coutil, two selection of the season’s weave. year. Specially priced for the color. Sizes up to 30 latest novelties, Saturday only, — hand-painted decorated Sizes 32 to 44. Sale — pair supporters. Sizes to 30 at SI.OO. THE FAIR Anniversary at (main floor). SI.OO 39c 19c -*=*TRAUGOTT BROS.—3II-325 W. Wash. St., 39c $1.19 69c 18th ANNIVERSARY SALE! Starts at 8:30 A. M. Tomorrow Offering Greater Values Than Ever Before Prices are the test of a “sale” and the test of a store's value to thepeople. 3,000 Pairs of WOMEN’S We have searched America for GOOD merchandise, and at the prices we 18th Anniversary Sale of offer it tomorrow you will agree we are doing a remarkable public service. This page advertisement is only a hasty sketch of thousands of items to APRON FROCKS HOSE Women’s pretty apron frocks, m be picture counters, racks made jm In this lot of 3,000 pairs of found here. The real is the merchandise on our of good quality percale, in neat Jm Jm Women’s Hose there are some and in our show cases. -

A Collection of Short Stories Scott Randall a Creative Writing Project

LEARNED HELPLESSNESS a collection of short stories by Scott Randall A Creative Writing Project submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research through English Language, Literature and Creative Writing in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts at the University of Windsor Windsor, Ontario, Canada 1998 Copyright 1998 Scott Randall National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1+1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellington Ottawa ON K 1A ON4 OrtawaON K1AON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or seii reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Acknowledgments 1 am grateful to Dr. John Ditsky and Dr. Alistair MacLeod for their tirne, their writing, and their warm, generous hearts. Thank you. for Sharon Anne and Katrina Ernber Contents First Impressions ........................................... -1 Two Ends of Time Are Neatïy Tied ............................