Interview with Bob Mitchler # VR2-A-L-2011-028.01 Interview # 1: June 29, 2011 Interviewer: Mark Depue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grunge Is Dead Is an Oral History in the Tradition of Please Kill Me, the Seminal History of Punk

THE ORAL SEATTLE ROCK MUSIC HISTORY OF GREG PRATO WEAVING TOGETHER THE DEFINITIVE STORY OF THE SEATTLE MUSIC SCENE IN THE WORDS OF THE PEOPLE WHO WERE THERE, GRUNGE IS DEAD IS AN ORAL HISTORY IN THE TRADITION OF PLEASE KILL ME, THE SEMINAL HISTORY OF PUNK. WITH THE INSIGHT OF MORE THAN 130 OF GRUNGE’S BIGGEST NAMES, GREG PRATO PRESENTS THE ULTIMATE INSIDER’S GUIDE TO A SOUND THAT CHANGED MUSIC FOREVER. THE GRUNGE MOVEMENT MAY HAVE THRIVED FOR ONLY A FEW YEARS, BUT IT SPAWNED SOME OF THE GREATEST ROCK BANDS OF ALL TIME: PEARL JAM, NIRVANA, ALICE IN CHAINS, AND SOUNDGARDEN. GRUNGE IS DEAD FEATURES THE FIRST-EVER INTERVIEW IN WHICH PEARL JAM’S EDDIE VEDDER WAS WILLING TO DISCUSS THE GROUP’S HISTORY IN GREAT DETAIL; ALICE IN CHAINS’ BAND MEMBERS AND LAYNE STALEY’S MOM ON STALEY’S DRUG ADDICTION AND DEATH; INSIGHTS INTO THE RIOT GRRRL MOVEMENT AND OFT-OVERLOOKED BUT HIGHLY INFLUENTIAL SEATTLE BANDS LIKE MOTHER LOVE BONE, THE MELVINS, SCREAMING TREES, AND MUDHONEY; AND MUCH MORE. GRUNGE IS DEAD DIGS DEEP, STARTING IN THE EARLY ’60S, TO EXPLAIN THE CHAIN OF EVENTS THAT GAVE WAY TO THE MUSIC. THE END RESULT IS A BOOK THAT INCLUDES A WEALTH OF PREVIOUSLY UNTOLD STORIES AND FRESH INSIGHT FOR THE LONGTIME FAN, AS WELL AS THE ESSENTIALS AND HIGHLIGHTS FOR THE NEWCOMER — THE WHOLE UNCENSORED TRUTH — IN ONE COMPREHENSIVE VOLUME. GREG PRATO IS A LONG ISLAND, NEW YORK-BASED WRITER, WHO REGULARLY WRITES FOR ALL MUSIC GUIDE, BILLBOARD.COM, ROLLING STONE.COM, RECORD COLLECTOR MAGAZINE, AND CLASSIC ROCK MAGAZINE. -

Weekly Intelligence Digest 3 November 1950

SECRET COPY NO. T'HE PACiFIC COMMAND 30 Fr INTELLIGENCE 21 NOV 1950 NUMBER• 4 4 - 5 0 • 0P32mflS 3 November 1950 DECLASSlflEIJ Authority 1✓Nrl__&l¥"YOO ,\ " SECR'E"T. FOR U.S. EYES ONLY The Weekl.7 Intelligence Digest ie published solely to disseminate intelllgenoe to sub ordinate units of the Pacific Command. Intelligence contained herein is the result or evaluati011 and' synthesis of all sources available to the Pacific Command. Lower echelon commandere or the Pacific Command are here b;y authorized to disseminate this intelligence to their commands on a med-to-know basis with proper security restrictions. Its use in formulating intelligence estimates is en- couraged. There is not objection to the use ot tbs Digest by addressees outside the Pacitic Com mand if it is UDderstood that the , secondaey nature of' its contents precludes its use as cont.11'1Zlation or arq pri!D8.!'7 source. The Digest Dimply represents current estimates and evaluation ot the Paci.tic Command im is by no means rigid. This document contains information atf'ecting _the national defense or the United State~ within the meaning ot the Espionage Act SO, Code 31 and 32, as amended. Its transmission or the revelation of' its contents in auy manner to an unauthorized person is prohibited bT law · • 'l'ramndssion b;y United States registered mail or registered guard mail is authorized in accordanoe with article, 7-5, United States 1favy Security lanual for Clasaified Matt.er, and the pertinent paragraphs ot Arrq Regulations 380-5. DISTRIBUTION {10-20-50) 22E. -

By Dead Reckoning by Bill Mciver

index Abernathy, Susan McIver 23 , 45–47 36 , 42 Acheson, Dean Bao Dai 464 and Korea 248 , 249 Barrish, Paul 373 , 427 first to state domino theory 459 Bataan, Battling Bastards of 332 Acuff, Roy 181 Bataan Death March 333 Adams, M.D 444 Bataan Gang. See MacArthur, Douglas Adams, Will 31 Bataan Peninsula 329–333 Adkisson, Paul L. 436. See also USS Colahan bathythermograph 455 Alameda, California 268 , 312 , 315 , 317 , 320 , Battle of Coral Seas 296–297 335 , 336 , 338 , 339 , 345 , 346 , 349 , Battle off Samars 291 , 292 , 297–298 , 303 , 351 , 354 , 356 306–309 , 438 Alamogordo, New Mexico 63 , 64 Bedichek, Roy 220 Albano, Sam 371 , 372 , 373 , 414 , 425 , 426 , Bee County, Texas 12 , 17 , 19 427 Beeville, Texas 19 Albany, Texas 161 Belfast, Ireland 186 Albuquerque, New Mexico 228 , 229 Bengal, Oklahoma 94 Allred, Lue Jeff 32 , 44 , 200 Bidault, Georges 497 , 510 Alpine, Texas 67 Big Cypress Bayou, Texas 33 Amarillo, Texas 66 , 88 , 122 , 198 , 431 Big Spring, Texas 58 , 61 , 68 , 74 , 255 , 256 Ambrose, Stephen Bikini Atoll. See Operation Castle on Truman’s decision 466 , 467 Bilyeau, Paul 519 , 523 , 526 Anderson County, Texas 35 Blick, Robert 487 , 500 , 505 , 510 Anson County, North Carolina 21 Blytheville, Arkansas 112 Appling, Luke 224 Bockius, R.W. 272 , 273 , 288 , 289 , 290 Arapaho Reservation 50 commended by Halsey 273 Archer City, Texas 50 , 55 , 74 , 104 , 200 , 201 , during typhoon 288 , 289 , 290 259 on carrier work 272 Argyllshire, Scotland 45 Boerne, Texas 68 Arnold, Eddie 181 Bonamarte, Joseph 20 Arrington, Fred 164 Booth, Sarah 433 Ashworth, Barbara 110 , 219 , 220 , 433 , 434 Boudreau, Lou 175 Ashworth, Don 219 , 433 Bowers, Gary 361 , 375 , 386 , 427 Ashworth, Kenneth 219 , 220 Bowie, James 244 Ashworth, Mae 199 , 219 , 220 Bradley, Omar 252 Ashworth, R.B. -

Kings Bay , Georgia

Cold War Up Periscope Nathan home War in Korea ends, What do you do Service dog matched but not Asian interests for family fun? with Wounded Warrior Page 12 Page 9 Page 13 THE kings bay, georgia VOL. 43 • ISSUE 48 , FLORIDA Vol. 48 • Issue 32 www.cnic.navy.mil/kingsbay kingsbayperiscope.jacksonville.com Thursday, August 22, 2013 Front, from left, CSSN Abdul Ney to USS Alaska Muhammad, CS3 Jeffrey The Capt. Edward F. Ney sonnel. White, Culinary award Memorial Award is an an- “The level of dedication our CSSA Victor added to list of nual awards, co-sponsored CSs have toward their craft Crawford; by the International Food is absolutely amazing,” said back, from SSBN’s honors Service C m d r . left, CSCM Execu- R o b e r t Cameron By MC1 James Kimber “... food is one of Submarine Group 10 Public Affairs t i v e s W i r t h , Kelsey, CS2 Asso- the biggest morale Alaska Zack Little, CS2 Jerome The Culinary Specialists ciation boosters ...” G o l d from the USS Alaska (SSBN (IF- com- Green, CS3 732) Gold crew were pre- S E A ) , Rear Adm. Mark Heinrich mand- Robert Gibson sented their trophy as the t h a t Navy Supply Systems Command ing offi- and Lt. j.g. top food service department encour- cer. “The Jared Givens in the submarine force Aug. a g e s N e y with the Ney 14 at an awards ceremony at excellence in Navy Food Award is one of the most Award. -

The Cauldron 2015

Mikaela Liotta, Cake Head Man, mixed media The Cauldron Senior Editors Grace Jaewon Yoo Muriel Leung Liam Nadire Staff Pann Boonbaichaiyapruck Phoebe Danaher Daniel Fung 2015 Sally Jee Prim Sirisuwannatash Angela Wong Melissa Yukseloglu Faculty Advisor Joseph McDonough 1 Poetry Emma Woodberry Remember 5 GyuHui Hwang Two Buttons Undone 6 Khanh Nyguen I Wait for You to Have Dinner 8 Angela Wong Euphoria 9 Sabi Benedicto The House was Supposed to be Tan 12 (But was Accidentally Painted Yellow) Canvas Li Haze 15 Adam Jolly Spruce and Hemlock Placed By 44 Gentle Hands Jordan Moller The Burning Cold 17 Grace Jaewon Yoo May 18 Silent Hills 40 Lindsay Wallace Forgotten 27 Joelle Troiano Flicker 30 Jack Bilbrough Untitled 31 Valentina Mathis A Hop Skip 32 Jessica Li The Passenger 36 Daddy’s Girl 43 Eugenia Rose stumps 38 Brandon Fong Ironing 47 Ryder Sammons Mixed Media, Ceramics New Year’s Cold 48 Mikaela Liotta Shayla Lamb Spine 7 Senior Year 50 Mermaid 46 Teddy Simson Elephant Skull 16 Prose Eye of the Tiger 53 Muriel Leung Katie I A Great River 20 Imagination 19 Zorte 52 Sabi Benedicto Geniophobia 32 2 Photography Rachel Choe More Please 8 Pann Boonbaichaiyapruck DEAD 2 Spin 12 Swimmingtotheschor 22 Bigfernfloating 41 Lydia Stenflo LA as seen from the 14 Griffith Observatory at Night in March Beach Warrior 58 Meimi Zhu Reflection 30 Jessica Li Juvenescence 37 The Last Door 42 Brandon Fong The End is Neigh 38 Sunday in Menemsha 53 Liam Nadire Hurricane Sandy #22 47 Pride 58 Painting, Drawing Katie I Risen 4 Oban Galbraith The Divide 9 Joni Leung -

Death, Difference, and Dialogue

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 1-1-2009 April 4, 1968: Death, Difference, and Dialogue Kristine Marie Warrenburg University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Warrenburg, Kristine Marie, "April 4, 1968: Death, Difference, and Dialogue" (2009). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 950. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/950 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. APRIL 4, 1968: DEATH, DIFFERENCE, AND DIALOGUE ROBERT F. KENNEDY ANNOUNCES THE ASSASSINATION OF MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR. __________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of Arts and Humanities University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________ by Kristine Warrenburg August 2009 Advisor: Darrin Hicks, Ph.D. ©Copyright by Kristine Warrenburg 2009 All Rights Reserved Author: Kristine Warrenburg Title: APRIL 4, 1968: DEATH, DIFFERENCE, AND DIALOGUE ROBERT F. KENNEDY ANNOUNCES THE ASSASSINATION OF MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR. Advisor: Darrin Hicks, Ph.D. Degree Date: August 2009 ABSTRACT Robert Kennedy’s announcement of the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., in an Indianapolis urban community that did not revolt in riots on April 4, 1968, provides one significant example in which feelings, energy, and bodily risk resonate alongside the articulated message. The relentless focus on Kennedy’s spoken words, in historical biographies and other critical research, presents a problem of isolated effect because the power really comes from elements outside the speech act. -

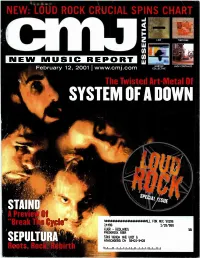

System of a Down Molds Metal Like Silly Putty, Bending and Shaping Its Parame- 12 Slayer's First Amendment Ters to Fit the Band's Twisted Vision

NEW: LOUD ROCK CRUCIAL SPINS CHART LOW TORTOISE 1111 NEW MUSIC REPORT Uà NORTEC JACK COSTANZO February 12, 20011 www.cmj.com COLLECTIVE The Twisted Art-Metal Of SYSTEM OF ADOWN 444****************444WALL FOR ADC 90138 24438 2/28/388 KUOR - REDLAHDS FREDERICK SUER S2V3HOD AUE unr G ATASCADER0 CA 88422-3428 IIii II i ti iii it iii titi, III IlitlIlli lilt ti It III ti ER THEIR SELF TITLED DEBUT AT RADIO NOW • FOR COLLEGE CONTACT PHIL KASO: [email protected] 212-274-7544 FOR METAL CONTACT JEN MEULA: [email protected] 212-274-7545 Management: Bryan Coleman for Union Entertainment Produced & Mixed by Bob Marlette Production & Engineering of bass and drum tracks by Bill Kennedy a OADRUNNEll ACME MCCOWN« ROADRUNNER www.downermusic.com www.roadrunnerrecords.com 0 2001 Roadrunner Records. Inc. " " " • Issue 701 • Vol 66 • No 7 FEATURES 8 Bucking The System member, the band is out to prove it still has Citing Jane's Addiction as a primary influ- the juice with its new release, Nation. ence, System Of A Down molds metal like Silly Putty, bending and shaping its parame- 12 Slayer's First Amendment ters to fit the band's twisted vision. Loud Follies Rock Editor Amy Sciarretto taps SOAD for Free speech is fodder for the courts once the scoop on its upcoming summer release. again. This time the principals involved are a headbanger institution and the parents of 10 It Takes A Nation daughter who was brutally murdered by three Some question whether Sepultura will ever of its supposed fans. be same without larger-than-life frontman 15 CM/A: Staincl Max Cavalera. -

GREEN, GREEN, & TENDER a Thesis Submitted to Kent State University

GREEN, GREEN, & TENDER A thesis submitted To Kent State University in partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts by Karly R. Milvet May, 2016 © Copyright All rights reserved Except for previously published materials Green, Green, & Tender written by Karly R. Milvet B.A., Kent State University, 2012 M.F.A., Kent State University, 2016 Approved by Catherine Wing , Advisor Robert Trogdon , Chair, Department of English James L. Blank , Dean, College of Arts and Science Table of Contents Part I Midnight, Tiny Tokyo..................................................................................................................... 2 Coming Over................................................................................................................................... 3 Someday Knowing.......................................................................................................................... 4 Advice I Should Have Taken.......................................................................................................... 6 [ ] .......................................................................................................................................... 7 Dear Anna....................................................................................................................................... 8 A Story of Origins......................................................................................................................... 10 A Poem Is the Threat Of What We’re -

June 2018.Pdf

MILITARY SEA SERVICES MUSEUM, INC. SEA SERVICES SCUTTLEBUTT June 2018 A message from the President Greetings, Summer arrived in Sebring. It has been very hot (high 80s, low 90s) the last couple of weeks. June also is start of the rainy and hurricane seasons in Florida and we have been receiving almost daily showers since late May. Hopefully our Northern members are enjoying cooler and drier air. So far this year we have had close to 600 visitors, hopefully headed for a record number of visitors for the year. Summer normally brings a decline in the number of visitors. This is a great time for visits from Scouts and other groups----can pretty much have the Museum to John Cecil themselves. Just let us know in advance when your group wants to visit (863) 385-0992 or [email protected]. We received many favorable comments on our Memorial Day observance. It was held in front of the Museum with attendees seated under a large tent. Towards the end of the observance, it began to rain and all attendees came inside the Museum where the observance was concluded. This also worked out well as we had a cake cutting ceremony planned inside to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the Museum which opened its doors as the Military Sea Services Museum on Memorial Day 1998. See additional comments and photos elsewhere in this "Scuttlebutt." Photos were provided by Fred Carino, Cris Carino, Diana Borders and Donald Laylock. Have a great summer. Stay safe! John Military Sea Services Museum Hours of Operation 1402 Roseland Avenue, Sebring, Open: Wednesday through Saturday Florida, 33870 Phone: (863) 385-0992 Noon to 4:00 p.m. -

Albert J. Baciocco, Jr. Vice Admiral, US Navy (Retired)

Albert J. Baciocco, Jr. Vice Admiral, U. S. Navy (Retired) - - - - Vice Admiral Baciocco was born in San Francisco, California, on March 4, 1931. He graduated from Lowell High School and was accepted into Stanford University prior to entering the United States Naval Academy at Annapolis, Maryland, in June 1949. He graduated from the Naval Academy in June 1953 with a Bachelor of Science degree in Engineering, and completed graduate level studies in the field of nuclear engineering in 1958 as part of his training for the naval nuclear propulsion program. Admiral Baciocco served initially in the heavy cruiser USS SAINT PAUL (CA73) during the final days of the Korean War, and then in the diesel submarine USS WAHOO (SS565) until April of 1957 when he became one of the early officer selectees for the Navy's nuclear submarine program. After completion of his nuclear training, he served in the commissioning crews of three nuclear attack submarines: USS SCORPION (SSN589), as Main Propulsion Assistant (1959-1961); USS BARB (SSN596), as Engineer Officer (1961-1962), then as Executive Officer (1963- 1965); and USS GATO (SSN615), as Commanding Officer (1965-1969). Subsequent at-sea assignments, all headquartered in Charleston, South Carolina, included COMMANDER SUBMARINE DIVISION FORTY-TWO (1969-1971), where he was responsible for the operational training readiness of six SSNs; COMMANDER SUBMARINE SQUADRON FOUR (1974-1976), where he was responsible for the operational and material readiness of fifteen SSNs; and COMMANDER SUBMARINE GROUP SIX (1981-1983), where, during the height of the Cold War, he was accountable for the overall readiness of a major portion of the Atlantic Fleet submarine force, including forty SSNs, 20 SSBNs, and various other submarine force commands totaling approximately 20,000 military personnel, among which numbered some forty strategic submarine crews. -

Cold War Allies: Commonwealth and United States Naval Cooperation in Asian Waters Edward J

Cold War Allies: Commonwealth and United States Naval Cooperation in Asian Waters Edward J. Marolda L’interaction entre les gouvernements canadiens, australiens, des États- Unis et du Royaume-Uni au cours de la guerre froide en Asie a été le plus souvent caractérisée par un désaccord sur les objectifs et la politique des États-Unis. Tel n’était pas le cas, cependant, avec l’expérience opérationnelle des marines de ces pays. En effet, les liens tissés entre les chefs des marines et des commandants de combat pendant les guerres de Corée et du Viêtnam ainsi que l’effort pour ramener la stabilité en Extrême-Orient, ont eu un impact positif sur la solidarité alliée et sur les mesures de sécurité collectives à la fin du 20ème et au 21ème siècles. Ce document traite de la nature de la relation opérationnelle entre les quatre marines dans la guerre de Corée; des actions navales américaines, britanniques et australiennes dans la gestion des conflits en Asie du Sud- Est au cours des années 50 et 60; l’expérience sous feu de la Marine royale australienne et la Marine américaine; et l’interaction vers la fin de la guerre froide pour faire face à la la présence et la montée en puissance de la marine soviétique dans les eaux asiatiques. The navies of the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand operated side by side with the navy of the United States throughout much of the Cold War in Asia. Despite often contentious policy disagreements between Washington and Commonwealth capitals, their navies functioned at high levels of coordination, interoperability, and efficiency. -

1.0 1.1 MICROFILMED by NPPSO-NAVAL Distria

1.0 2.5 lU ^t 2.2 S E4 ^ « a2.0 1.1 1.8 DATE /2l^^ 1.25 1.4 1.6 jZ J '' ,;'Jh'^- |^g^4(z^y'j/F^^L^->4'<r //2> / ^/S'<D /i^ j/^ MICROFILMED BY NPPSO-NAVAL DISTRia WASHINGTON ilCROFILM SECTION REEL TARGET - START AND END NDW-NPPSO-5210/1 (6.-78) Office of Kaval Records-and History Ships' Histories Section Havy Department ; • HISTORY'OP USS MASSEY (DD 778) • The USS MASSEY, one of the Navy's nev 2,200 ton destroyers, has had an eventful career. She was. built at the Seattle plant of the Todd-Pacific Shipbuilding Company. Mrs. Lance E. Massey christened the ship on Septem'ber- 12, 19^4, in honor of her late' husband,, Lieu• tenant Commander Lance E. Massey, USN, one of the early heroes of the Pacific- war. As the Commander of Torpedo Squadron Three in the Battle of Midway, Commander Massey died pressing home an assault through in• tense antiaircraft and fighter opposition that resulted In the sinking of two Japanese aircraft carriers. .On November 24, 1944, in Seattle, the USS MASSEY was officially placed in commission with Commander Charles W, Aldrich, USN,- as her first 'commanding officer. For the next week, the MASSEY continued • on her final outfitting alongside the dock before getting underway on • .'November 50 on the first of her pre-shakedown trial runs. After con• ducting various gunnery, radar, and degauslng tests and-exercises in .the.Puget Sound area, the MASSEY departed for San Diego on December 12. Here she underwent six weeks of various drills and inspections climaxed by her final military Inspection of January 25.