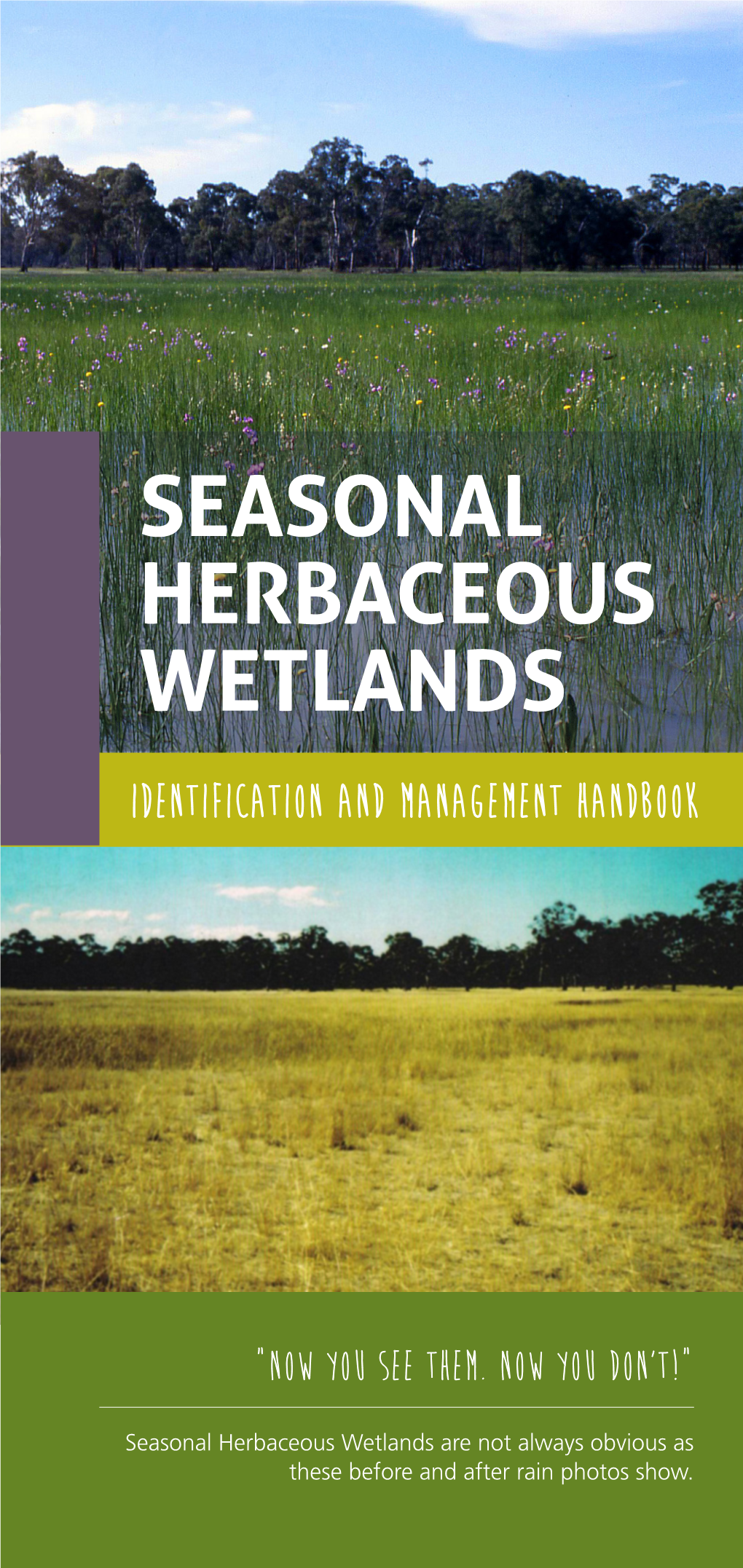

Seasonal Herbaceous Wetlands Identification and Management Handbook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A REVISION of TRISETUM Victor L. Finot,' Paul M

A REVISION OF TRISETUM Victor L. Finot,' Paul M. Peterson,3 (POACEAE: POOIDEAE: Fernando 0 Zuloaga,* Robert J. v sorene, and Oscar Mattnei AVENINAE) IN SOUTH AMERICA1 ABSTRACT A taxonomic treatment of Trisetum Pers. for South America, is given. Eighteen species and six varieties of Trisetum are recognized in South America. Chile (14 species, 3 varieties) and Argentina (12 species, 5 varieties) have the greatest number of taxa in the genus. Two varieties, T. barbinode var. sclerophyllum and T longiglume var. glabratum, are endemic to Argentina, whereas T. mattheii and T nancaguense are known only from Chile. Trisetum andinum is endemic to Ecuador, T. macbridei is endemic to Peru, and T. foliosum is endemic to Venezuela. A total of four species are found in Ecuador and Peru, and there are two species in Venezuela and Colombia. The following new species are described and illustrated: Trisetum mattheii Finot and T nancaguense Finot, from Chile, and T pyramidatum Louis- Marie ex Finot, from Chile and Argentina. The following two new combinations are made: T barbinode var. sclerophyllum (Hack, ex Stuck.) Finot and T. spicatum var. cumingii (Nees ex Steud.) Finot. A key for distinguishing the species and varieties of Trisetum in South America is given. The names Koeleria cumingii Nees ex Steud., Trisetum sect. Anaulacoa Louis-Marie, Trisetum sect. Aulacoa Louis-Marie, Trisetum subg. Heterolytrum Louis-Marie, Trisetum subg. Isolytrum Louis-Marie, Trisetum subsect. Koeleriformia Louis-Marie, Trisetum subsect. Sphenopholidea Louis-Marie, Trisetum ma- lacophyllum Steud., Trisetum variabile E. Desv., and Trisetum variabile var. virescens E. Desv. are lectotypified. Key words: Aveninae, Gramineae, Poaceae, Pooideae, Trisetum. -

Technical Protocols for Program Outcomes

Monitoring and Reporting Framework: Technical Protocols for Program Outcomes Melbourne Strategic Assessment © The State of Victoria Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning 2015 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. You are free to re-use the work under that licence, on the condition that you credit the State of Victoria as author. The licence does not apply to any images, photographs or branding, including the Victorian Coat of Arms, the Victorian Government logo and the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning logo. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en ISBN 978-1-74146-577-8 Accessibility If you would like to receive this publication in an alternative format, please telephone the DELWP Customer Service Centre on 136186, email [email protected] or via the National Relay Service on 133 677 www.relayservice.com.au. This document is also available on the internet at www.delwp.vic.gov.au Disclaimer This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence which may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. Contents Introduction 5 Context and scope 5 Monitoring Program Outcomes 5 Reporting on Program Outcomes 8 The composition, structure and function of Natural -

Cravens Peak Scientific Study Report

Geography Monograph Series No. 13 Cravens Peak Scientific Study Report The Royal Geographical Society of Queensland Inc. Brisbane, 2009 The Royal Geographical Society of Queensland Inc. is a non-profit organization that promotes the study of Geography within educational, scientific, professional, commercial and broader general communities. Since its establishment in 1885, the Society has taken the lead in geo- graphical education, exploration and research in Queensland. Published by: The Royal Geographical Society of Queensland Inc. 237 Milton Road, Milton QLD 4064, Australia Phone: (07) 3368 2066; Fax: (07) 33671011 Email: [email protected] Website: www.rgsq.org.au ISBN 978 0 949286 16 8 ISSN 1037 7158 © 2009 Desktop Publishing: Kevin Long, Page People Pty Ltd (www.pagepeople.com.au) Printing: Snap Printing Milton (www.milton.snapprinting.com.au) Cover: Pemberton Design (www.pembertondesign.com.au) Cover photo: Cravens Peak. Photographer: Nick Rains 2007 State map and Topographic Map provided by: Richard MacNeill, Spatial Information Coordinator, Bush Heritage Australia (www.bushheritage.org.au) Other Titles in the Geography Monograph Series: No 1. Technology Education and Geography in Australia Higher Education No 2. Geography in Society: a Case for Geography in Australian Society No 3. Cape York Peninsula Scientific Study Report No 4. Musselbrook Reserve Scientific Study Report No 5. A Continent for a Nation; and, Dividing Societies No 6. Herald Cays Scientific Study Report No 7. Braving the Bull of Heaven; and, Societal Benefits from Seasonal Climate Forecasting No 8. Antarctica: a Conducted Tour from Ancient to Modern; and, Undara: the Longest Known Young Lava Flow No 9. White Mountains Scientific Study Report No 10. -

Solar River Project the Solar River Project Pty

Solar River Project The Solar River Project Pty Ltd Data Report - Appendices Cnr Dartmoor Road and Bower Boundary Road, Maude, South Australia 8 March 2018 Solar River Project Data Report - Appendices Cnr Dartmoor Road and Bower Boundary Road, Maude, South Australia Kleinfelder Document Number: NCA18R71494 Project No: 20183040 All Rights Reserved Prepared for: THE SOLAR RIVER PROJECT PTY LTD 10 PULTENEY STREET ADELAIDE, SA, 5000 Only The Solar River Project Pty Ltd, its designated representatives or relevant statutory authorities may use this document and only for the specific project for which this report was prepared. It should not be otherwise referenced without permission. Document Control: Version Description Date Author Technical Reviewer Peer Reviewer P. Fagan and P. 1.0 Draft Data Report 7 March 2018 P. Barron S. Schulz Barron P. Fagan and P. 2.0 Final Data Report 8 March 2018 P. Barron S. Schulz Barron Kleinfelder Australia Pty Ltd Newcastle Office 95 Mitchell Road Cardiff NSW 2285 Phone: (02) 4949 5200 ABN: 23 146 082 500 Ref: NCA18R71494 Page i 8 March 2018 Copyright 2018 Kleinfelder APPENDIX 1. FLORA SPECIES LIST Transmission No. Family Common Name Main Site Scientific Name Line Easement 1. Aizoaceae Tetragonia eremaea Desert Spinach Y 2. Anacardiaceae *Schinus molle Pepper-tree Y 3. Asteraceae *Onopordum acaulon Stemless Thistle Y Y 4. Asteraceae *Carthamus lanatus Saffron Thistle Y Y 5. Asteraceae *Xanthium spinosum Bathurst Burr Y 6. Asteraceae Brachyscome ciliaris Variable Daisy Y Cratystylis 7. Asteraceae Bluebush Daisy Y conocephala 8. Asteraceae Leiocarpa websteri Narrow Plover-daisy Y Y Crinkle-leaf Daisy- 9. Asteraceae Y Olearia calcarea bush 10. -

Full Article

Volume 3(4): 599 TELOPEA Publication Date: 12 April 1990 Til. Ro)'al BOTANIC GARDENS dx.doi.org/10.7751/telopea19904909 Journal of Plant Systematics 6 DOPII(liPi Tm st plantnet.rbgsyd.nsw.gov.au/Telopea • escholarship.usyd.edu.au/journals/index.php/TEL· ISSN 0312-9764 (Print) • ISSN 2200-4025 (Online) Telopea Vol. 3(4): 599 (1990) 599 SHORT COMMUNICATION Amphibromus nervosus (Poaceae), an earlier combination and further synonyms Arthur Chapman, Bureau of Flora & Fauna, Canberra, has kindly pointed out to me that the combination Amphibromus nervosus (J. D. Hook.) Baillon had been made in 1893, earlier than the combination made by G. C. Druce re ported in our revision of the genus Amphibromus in Australia (Jacobs and Lapinpuro 1986). Baillon's combination had been overlooked by Index Kewensis and by the Chase Index (Chase and Niles 1962). The full citation is: Amphibromus nervosus (J. D. Hook.) Baillon, Histoire des Plantes 12: 203 (1893). BASIONYM: Danthonia nervosa J. D. Hook., Fl.FI. Tasm. 2: 121, pI.pl. 163A (1858). Hooker based his combination on the illegitimate Avena nervosa R. Br. (see Jacobs and Lapinpuro 1986 for further comment). Amphibromus nervosus (1. D. Hook.) G. C. Druce then becomes a superfluous combina tion and is added to the synonymy. Arthur Chapman also kindly pointed out a synonym that to the best of my knowledge has not been used beyond its initial publication. This synonym is: Avenastrum nervosum Vierh., Verhandlungen der Gesellschaft Deutscher Naturforscher und Artze 85. Versammlung zu Wien (Leipzig) 1: 672 (1913). This name was based on the illegitimate Avena nervosa R. -

Vegetation and Floristics of Naree and Yantabulla

Vegetation and Floristics of Naree and Yantabulla Dr John T. Hunter June 2015 23 Kendall Rd, Invergowrie NSW, 2350 Ph. & Fax: (02) 6775 2452 Email: [email protected] A Report to the Bush Heritage Australia i Vegetation of Naree & Yantabulla Contents Summary ................................................................................................................ i 1 Introduction ....................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Objectives ....................................................................................... 1 2 Methodology ...................................................................................................... 2 2.1 Site and species information ......................................................... 2 2.2 Data management ......................................................................... 3 2.3 Multivariate analysis ..................................................................... 3 2.4 Significant vascular plant taxa within the study area ............... 5 2.5 Mapping ......................................................................................... 5 2.6 Mapping caveats ............................................................................ 8 3 Results ................................................................................................................ 9 3.1 Site stratification ........................................................................... 9 3.2 Floristics ...................................................................................... -

Native Plants Sixth Edition Sixth Edition AUSTRALIAN Native Plants Cultivation, Use in Landscaping and Propagation

AUSTRALIAN NATIVE PLANTS SIXTH EDITION SIXTH EDITION AUSTRALIAN NATIVE PLANTS Cultivation, Use in Landscaping and Propagation John W. Wrigley Murray Fagg Sixth Edition published in Australia in 2013 by ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Reed New Holland an imprint of New Holland Publishers (Australia) Pty Ltd Sydney • Auckland • London • Cape Town Many people have helped us since 1977 when we began writing the first edition of Garfield House 86–88 Edgware Road London W2 2EA United Kingdom Australian Native Plants. Some of these folk have regrettably passed on, others have moved 1/66 Gibbes Street Chatswood NSW 2067 Australia to different areas. We endeavour here to acknowledge their assistance, without which the 218 Lake Road Northcote Auckland New Zealand Wembley Square First Floor Solan Road Gardens Cape Town 8001 South Africa various editions of this book would not have been as useful to so many gardeners and lovers of Australian plants. www.newhollandpublishers.com To the following people, our sincere thanks: Steve Adams, Ralph Bailey, Natalie Barnett, www.newholland.com.au Tony Bean, Lloyd Bird, John Birks, Mr and Mrs Blacklock, Don Blaxell, Jim Bourner, John Copyright © 2013 in text: John Wrigley Briggs, Colin Broadfoot, Dot Brown, the late George Brown, Ray Brown, Leslie Conway, Copyright © 2013 in map: Ian Faulkner Copyright © 2013 in photographs and illustrations: Murray Fagg Russell and Sharon Costin, Kirsten Cowley, Lyn Craven (Petraeomyrtus punicea photograph) Copyright © 2013 New Holland Publishers (Australia) Pty Ltd Richard Cummings, Bert -

Tracing History

Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Science and Technology 911 Tracing History Phylogenetic, Taxonomic, and Biogeographic Research in the Colchicum Family BY ANNIKA VINNERSTEN ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS UPPSALA 2003 Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Lindahlsalen, EBC, Uppsala, Friday, December 12, 2003 at 10:00 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Abstract Vinnersten, A. 2003. Tracing History. Phylogenetic, Taxonomic and Biogeographic Research in the Colchicum Family. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Science and Technology 911. 33 pp. Uppsala. ISBN 91-554-5814-9 This thesis concerns the history and the intrafamilial delimitations of the plant family Colchicaceae. A phylogeny of 73 taxa representing all genera of Colchicaceae, except the monotypic Kuntheria, is presented. The molecular analysis based on three plastid regions—the rps16 intron, the atpB- rbcL intergenic spacer, and the trnL-F region—reveal the intrafamilial classification to be in need of revision. The two tribes Iphigenieae and Uvularieae are demonstrated to be paraphyletic. The well-known genus Colchicum is shown to be nested within Androcymbium, Onixotis constitutes a grade between Neodregea and Wurmbea, and Gloriosa is intermixed with species of Littonia. Two new tribes are described, Burchardieae and Tripladenieae, and the two tribes Colchiceae and Uvularieae are emended, leaving four tribes in the family. At generic level new combinations are made in Wurmbea and Gloriosa in order to render them monophyletic. The genus Androcymbium is paraphyletic in relation to Colchicum and the latter genus is therefore expanded. -

Aspects of the Distribution, Phytosociology, Ecology and Management of Danthonia Popinensis 0.1. Morris, an Endangered Wallaby Grass from Tasmania

Papers and Proceedings o/the Royal Society o/Tasmania, Volume 131, 1997 31 ASPECTS OF THE DISTRIBUTION, PHYTOSOCIOLOGY, ECOLOGY AND MANAGEMENT OF DANTHONIA POPINENSIS 0.1. MORRIS, AN ENDANGERED WALLABY GRASS FROM TASMANIA by Louise Gilfedder and J.B. Kirkpatrick (with four tables and two text-figures) GILFEDDER, LOUISE & KIRKPATRICK, ]. B., 1997 (31 :viii): Aspects of the distribution, phytosociology, ecology and management of Danthonia popinensis D.1. Morris, an endangered wallaby grass from Tasmania. ISSN 0080-4703. Pap. Proc. R. Soc. Tasm. 131: 31-35. Parks and Wildlife Service, GPO Box 44A Hobart, Tasmania, Australia 7001, formerly Department of Geography and Environmental Studies (LG); Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, University of Tasmania, GPO Box 252- 78, Hobart, Tasmania, Australia 7001 GBK). Danthonia popinensis is a recently discovered, nationally endangered tussock grass, originally known from only one roadside population at Kempton, Tasmania. Six populations have been recorded, all from flat land with mildly acid non-rocky soils, and all in small toadside or paddock remnants, badly invaded by exotic plants. However, one site has recently been destroyed through roadworks. The species germinates best at temperatures of 10°e, indicating a winter germination strategy. Autumn burning at Kempton resulted in an increased cover of D. popinensis two years after the burn, but also resulted in an increased cover of competitive exotics. The future of the species needs to be secured by ex situ plantings, as almost all of its original habitat has been converted to crops or improved pasture. Key Words: Danthonia popinensis, wallaby grass, tussock grass, endangered species, Tasmania. INTRODUCTION common fire management regime (e.g. -

Common Spikerush Eleocharis Acuta

Eleocharis acuta CYPERACEAE Common spikerush Inflorescence Avon Catchment Council Eleocharis acuta Common spikerush Plant features Growth form Perennial, spreading sedge, up to 0.7m high, with slender creeping rhizomes from which new stems arise. It often forms extensive colonies across shallow waterbodies. CYPERACEAE Leaves The stems are light to medium green, 1-3mm wide, circular in cross section and up to 0.7m in length. The leaves are reduced to one or more purplish sheaths around the base, with the upmost leaf having a needle-like blade. Flowers The inflorescence is at the top of stems and is a single spikelet 10-30mm long and 3-7mm wide, making the stem and inflorescence look somewhat like a spear. The spikelet contains several small flowers. Flowers brown and occur from Sep-Dec. Fruits The nut is smooth, brown, slightly compressed and 1mm wide by 1.5-2mm long. Distribution An common wetland species from Carnarvon to east of Esperance and Floodfringe Kalgoorlie with scattered populations Floodway in the Avon catchment. Occurs in all Normal winter level other states. Prefered habitat of Eleocharis acuta Zone, habitat Occurs in fresh, seasonally waterlogged waterways including creek banks, swamps, floodways, seeps, clay pans and lake edges. Found in most soil types. Additional information It is an excellent soil stabiliser and nutrient stripper for winter wet waterbodies due to its network of roots and dense foliage at the soil surface. It often forms dense colonies around waterbodies and can be the dominant species. Tolerates a wide range of water levels. Also has the ability to pump oxygen into the sediment, which assists with essential microbial activity. -

Phenotypic Landscape Inference Reveals Multiple Evolutionary Paths to C4 Photosynthesis

RESEARCH ARTICLE elife.elifesciences.org Phenotypic landscape inference reveals multiple evolutionary paths to C4 photosynthesis Ben P Williams1†, Iain G Johnston2†, Sarah Covshoff1, Julian M Hibberd1* 1Department of Plant Sciences, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom; 2Department of Mathematics, Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom Abstract C4 photosynthesis has independently evolved from the ancestral C3 pathway in at least 60 plant lineages, but, as with other complex traits, how it evolved is unclear. Here we show that the polyphyletic appearance of C4 photosynthesis is associated with diverse and flexible evolutionary paths that group into four major trajectories. We conducted a meta-analysis of 18 lineages containing species that use C3, C4, or intermediate C3–C4 forms of photosynthesis to parameterise a 16-dimensional phenotypic landscape. We then developed and experimentally verified a novel Bayesian approach based on a hidden Markov model that predicts how the C4 phenotype evolved. The alternative evolutionary histories underlying the appearance of C4 photosynthesis were determined by ancestral lineage and initial phenotypic alterations unrelated to photosynthesis. We conclude that the order of C4 trait acquisition is flexible and driven by non-photosynthetic drivers. This flexibility will have facilitated the convergent evolution of this complex trait. DOI: 10.7554/eLife.00961.001 Introduction *For correspondence: Julian. The convergent evolution of complex traits is surprisingly common, with examples including camera- [email protected] like eyes of cephalopods, vertebrates, and cnidaria (Kozmik et al., 2008), mimicry in invertebrates and †These authors contributed vertebrates (Santos et al., 2003; Wilson et al., 2012) and the different photosynthetic machineries of equally to this work plants (Sage et al., 2011a). -

Ecological Differentiation of Combined and Separate Sexes of Wurmbea Dioica (Colchicaceae) in Sympatry

Ecology, 82(9), 2001, pp. 2601±2616 q 2001 by the Ecological Society of America ECOLOGICAL DIFFERENTIATION OF COMBINED AND SEPARATE SEXES OF WURMBEA DIOICA (COLCHICACEAE) IN SYMPATRY ANDREA L. CASE1 AND SPENCER C. H. BARRETT Department of Botany, University of Toronto, 25 Willcocks Street, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5S 3B2 Abstract. The evolution and maintenance of combined vs. separate sexes in ¯owering plants is in¯uenced by both ecological and genetic factors; variation in resources, partic- ularly moisture availability, is thought to play a role in selection for gender dimorphism in some groups. We investigated the density, distribution, biomass allocation, and physi- ology of sympatric monomorphic (cosexual) and dimorphic (female and male) populations of Wurmbea dioica in relation to soil moisture on the Darling Escarpment in southwestern Australia. Populations with monomorphic vs. dimorphic sexual systems segregated into wet vs. dry microsites, respectively, and biomass allocation patterns and physiological traits re¯ected differences in water availability, despite similarities in total ramet biomass between the sexual systems. Unisexuals ¯owered earlier at lower density, and they allocated sig- ni®cantly more biomass below ground to roots and corms than did cosexuals, which al- located more biomass above ground to leaves, stems, and ¯owers. Females, males, and cosexuals produced similar numbers of ¯owers per ramet, but unisexuals produced more ramets than cosexuals, increasing the total number of ¯owers per genet. Contrary to ex- pectation, cosexuals had signi®cantly higher (more positive) leaf carbon isotope ratios and lower leaf nitrogen content than unisexuals, suggesting that cosexuals are more water-use ef®cient and have lower rates of photosynthesis per unit leaf mass despite their occurrence in wetter microsites.