Biodiversity Values on Selected Kimberley Islands, Australia Edited

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

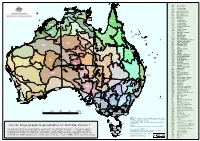

Australia's 89 Bioregions (PDF

ARC Arnhem Coast ARP Arnhem Plateau TIW AUA Australian Alps AVW Avon Wheatbelt BBN Brigalow Belt North DARWIN ! ARC BBS Brigalow Belt South BEL Ben Lomond ITI DAC PCK ARP BHC Broken Hill Complex CEA BRT Burt Plain CAR Carnarvon ARC CEA Central Arnhem DAB CYP CEK Central Kimberley CER Central Ranges NOK VIB CHC Channel Country CMC Central Mackay Coast GUC COO Coolgardie GFU STU COP Cobar Peneplain COS Coral Sea CEK CYP Cape York Peninsula OVP DAB Daly Basin DAC Darwin Coastal DAL WET GUP EIU DAL Dampierland DEU Desert Uplands DMR Davenport Murchison Ranges COS DRP Darling Riverine Plains DMR TAN EIU Einasleigh Uplands MII ESP Esperance Plains GSD EYB Eyre Yorke Block FIN Finke FLB Flinders Lofty Block CMC FUR Furneaux BRT GAS Gascoyne PIL DEU GAW Gawler MGD BBN GES Geraldton Sandplains GFU Gulf Fall and Uplands MAC GID Gibson Desert LSD GID GSD Great Sandy Desert GUC Gulf Coastal GUP Gulf Plains CAR GAS CER FIN CHC GVD Great Victoria Desert HAM Hampton ITI Indian Tropical Islands SSD JAF Jarrah Forest KAN Kanmantoo KIN King GVD LSD Little Sandy Desert STP BBS MUR SEQ MAC MacDonnell Ranges MUL MAL Mallee ! BRISBANE MDD Murray Darling Depression YAL MGD GES Mitchell Grass Downs STP MII Mount Isa Inlier MUL Mulga Lands NUL MUR Murchison NAN Nandewar GAW NET NCP Naracoorte Coastal Plain SWA COO NAN NET New England Tablelands AVW HAM BHC DRP NNC NSW North Coast FLB NOK Northern Kimberley ! COP PERTH NSS NSW South Western Slopes MDD NNC NUL Nullarbor MAL EYB OVP Ord Victoria Plain PCK Pine Creek JAF ESP SYB PSI PIL Pilbara ADELAIDE ! ! PSI Pacific -

House of Representatives Standing Committee on the Environment and Energy

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES STANDING COMMITTEE ON THE ENVIRONMENT AND ENERGY Inquiry into controlling the spread of Cane Toads SUBMISSION FROM THE DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT AND ENERGY February 2019 Contents a) EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................. 3 b) National coordination................................................................................................................... 4 Cane Toads: Impacts on Matters of National Environmental Significance ..................................... 5 c) Roles of the Department of the Environment and Energy ........................................................... 6 Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 .................................................. 6 Funding ......................................................................................................................................... 10 National Park Management.......................................................................................................... 10 Information ................................................................................................................................... 11 d) Inquiry Terms of Reference ........................................................................................................ 11 The effectiveness of control measures to limit the spread of cane toads in Australia. ............... 11 Additional support for cane toad population control measures. -

Part B: Terrestrial Environments Overview

Part B: Terrestrial Environments Norm McKenzie, Tony Start, Andrew Burbidge, Kevin Kenneally and Neil Burrows Overview The Kimberley extends from sub-humid to semi-arid areas and covers a variety of different geological basements. These differences are reflected in the distinctive geomorphologies, soil, landscapes and biotas of the north, central, south and eastern Kimberley, and have determined their different land-use histories and contemporary land condition. In these terms, five biogeographical regions (10 subregions) are recognised in the Kimberley (Thackway and Cresswell 1995, McKenzie et al. 2003), that provide a framework for planning and action. In this section, we review the information base then characterise the bioregions to identify their different contributions to Kimberley diversity (treated here as a mosaic of regional ecosystems). Then we summarise the biodiversity values of Kimberley ecosystems and identify special features, communities, clades and species that should be a particular focus for management because of rarity, special value, vulnerability or imminent risk. Next, we review the condition and trend of the ecosystems in each bioregion, and provide a schematic model of the soil nutrient, hydrological and inter-species processes that maintain the compositional diversity of savanna because it is the matrix in which all of the Kimberley’s other ecosystems and special features are set. Finally, we identify priority management needs, particularly strategic actions that will mitigate degrading processes throughout the Kimberley and protect or rehabilitate whole suites of ecosystems and species. Healthy country is more productive, both in economic and biodiversity terms (Whitehead et al. 2000, Start 2003). The most cost effective conservation strategy is to protect, restore and maintain functional landscapes and systems, rather than trying to preserve small remnants or focussing only on localised, patch-scale remedial actions such as site restoration. -

West Kimberley Place Report

WEST KIMBERLEY PLACE REPORT DESCRIPTION AND HISTORY ONE PLACE, MANY STORIES Located in the far northwest of Australia’s tropical north, the west Kimberley is one place with many stories. National Heritage listing of the west Kimberley recognises the natural, historic and Indigenous stories of the region that are of outstanding heritage value to the nation. These and other fascinating stories about the west Kimberley are woven together in the following description of the region and its history, including a remarkable account of Aboriginal occupation and custodianship over the course of more than 40,000 years. Over that time Kimberley Aboriginal people have faced many challenges and changes, and their story is one of resistance, adaptation and survival, particularly in the past 150 years since European settlement of the region. The listing also recognizes the important history of non-Indigenous exploration and settlement of the Kimberley. Many non-Indigenous people have forged their own close ties to the region and have learned to live in and understand this extraordinary place. The stories of these newer arrivals and the region's distinctive pastoral and pearling heritage are integral to both the history and present character of the Kimberley. The west Kimberley is a remarkable part of Australia. Along with its people, and ancient and surviving Indigenous cultural traditions, it has a glorious coastline, spectacular gorges and waterfalls, pristine rivers and vine thickets, and is home to varied and unique plants and animals. The listing recognises these outstanding ecological, geological and aesthetic features as also having significance to the Australian people. In bringing together the Indigenous, historic, aesthetic, and natural values in a complementary manner, the National Heritage listing of the Kimberley represents an exciting prospect for all Australians to work together and realize the demonstrated potential of the region to further our understanding of Australia’s cultural history. -

Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation for Australia, Version 7 Data Used Are Assumed to Be Correct As Received from the Data Suppliers

ARC Arnhem Coast ARP Arnhem Plateau TIW AUA Australian Alps AVW Avon Wheatbelt DARWIN BBN Brigalow Belt North ARC BBS Brigalow Belt South BEL Ben Lomond ITI DAC PCK ARP BHC Broken Hill Complex CEA BRT Burt Plain CAR Carnarvon ARC CEA Central Arnhem DAB CYP CEK Central Kimberley CER Central Ranges NOK VIB CHC Channel Country CMC Central Mackay Coast GUC COO Coolgardie GFU STU COP Cobar Peneplain COS Coral Sea CEK CYP Cape York Peninsula OVP DAB Daly Basin DAC Darwin Coastal DAL WET GUP EIU DAL Dampierland DEU Desert Uplands DMR Davenport Murchison Ranges COS DRP Darling Riverine Plains DMR TAN EIU Einasleigh Uplands MII ESP Esperance Plains GSD EYB Eyre Yorke Block FIN Finke FLB Flinders Lofty Block CMC FUR Furneaux BRT GAS Gascoyne PIL DEU GAW Gawler MGD BBN GES Geraldton Sandplains GFU Gulf Fall and Uplands MAC GID Gibson Desert LSD GID GSD Great Sandy Desert GUC Gulf Coastal GUP Gulf Plains CAR GAS CER FIN CHC GVD Great Victoria Desert HAM Hampton ITI Indian Tropical Islands SSD JAF Jarrah Forest KAN Kanmantoo KIN King GVD LSD Little Sandy Desert STP BBS MUR SEQ MAC MacDonnell Ranges MUL BRISBANE MAL Mallee MDD Murray Darling Depression YAL MGD GES Mitchell Grass Downs STP MII Mount Isa Inlier MUL Mulga Lands NUL MUR Murchison NAN Nandewar GAW NET NCP Naracoorte Coastal Plain SWA COO NAN NET New England Tablelands AVW HAM BHC DRP NNC NSW North Coast FLB NOK Northern Kimberley PERTH COP NSS NSW South Western Slopes MDD NNC NUL Nullarbor MAL EYB OVP Ord Victoria Plain PCK Pine Creek JAF ESP SYB PIL Pilbara ADELAIDE SYDNEY PSI PSI Pacific -

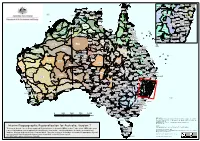

Terrestrial Protected Areas - IBRA Boundaries

Appendix 7 Terrestrial protected areas - IBRA boundaries AA Australian Alps TIW ARC Arnhem Coast Terrestrial Protected Areas - ARP Arnhem Plateau ARC AW Avon Wheatbelt 80,895,099 hectares (10.52%) BBN Brigalow Belt North DARWIN BBS Brigalow Belt South DAC ARP BEL Ben Lomond PCK CA BHC Broken Hill Complex BRT Burt Plain CA Central Arnhem DAB CYP CAR Carnarvon CHC Channel Country NK VB CK Central Kimberley GUC CMC Central Mackay Coast GFU COO Coolgardie STU CP Cobar Peneplain CR Central Ranges CK OVP CYP Cape York Peninsula DAB Daly Basin DL WT DAC Darwin Coastal GUP EIU DEU Desert Uplands DL Dampierland DMR Davenport Murchison Ranges DMR DRP Darling Riverine Plains TAN EIU Einasleigh Uplands MII ESP Esperance Plains GSD EYB Eyre Yorke Block FIN Finke FLB Flinders Lofty Block MGD BRT CMC FLI Flinders PIL DEU GAS Gascoyne BBN GAW Gawler GD Gibson Desert MAC GFU Gulf Fall and Uplands LSD GD GS Geraldton Sandplains GSD Great Sandy Desert CR FIN GUC Gulf Coastal CAR GAS GUP Gulf Plains CHC GVD Great Victoria Desert HAM Hampton SSD JF Jarrah Forest BBS KAN Kanmantoo SEQ KIN King STP ML LSD Little Sandy Desert MUR GVD BRISBANE MAC MacDonnell Ranges MAL Mallee MDD Murray Darling Depression GS YA L MGD Mitchell Grass Downs MII Mount Isa Inlier ML Mulga Lands NUL MUR Murchison NAN NAN Nandewar GAW DRP NET NCP Naracoorte Coastal Plain AW COO BHC NET New England Tablelands FLB NK Northern Kimberley PERTH HAM CP NNC NSW North Coast NSS NSW South Western Slopes SWA NNC MAL EYB NUL Nullarbor OVP Ord Victoria Plain JF SB PCK Pine Creek ESP NSS PIL Pilbara RIV SYDNEY RIV Riverina ADELAIDE SB Sydney Basin SEH ± WAR MDD SCP South East Coastal Plain 200100 0 200 400 KAN SEC South East Corner SEH South Eastern Highlands NCP AA SEQ South Eastern Queensland Kilometres VM SSD Simpson Strzelecki Dunefields Sources: STP Stony Plains IBRA 6.1 - IBRA Version 6.1 (2004), Australian Government Department of the Environment and VVP SEC STU Sturt Plateau Heritage through compilation of State/Territory SCP SWA Swan Coastal Plain datasets. -

Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation for Australia, Version 7 KIN01 Data Used Are Assumed to Be Correct As Received from the Data Suppliers

SEQ02 SEQ04 BBS17 BBS20 BBS19 BBS18 SEQ03 SEQ10 CYP03 SEQ11 TIW02 ARC05 NAN01 NET15 TIW01 ARC01 NNC02 CYP04 ARC02 BBS22 NET12 SEQ13 DAC01 DRP03 NET14 NNC18 ITI03 ARP01 BBS21 DARWIN ARC03 NET10 NET06 PCK01 ARP02 SEQ12 CEA02 NAN02 NET11 CEA01 CYP07 NET07 NNC03 NNC05 VIB02 NET17 ARC04 NET18 CYP01 NAN03 NET09 NNC04 DAB01 CYP09 NET01 NET05 NOK02 BBS23 NET16 NET08 NNC06 CYP08 NET04 VIB01 VIB03 CYP06 NAN04 NET13 NOK01 STU03 GUC02 NNC08 GFU01 GUC01 CYP02 NNC09 OVP03 NNC07 CYP05 BBS25 NNC10 GUP10 NET03 STU02 WET09 CEK01 GUP04 EIU03 CEK03 OVP01 GUP06 WET08 NNC11 GUP07 BBS24 OVP04 GFU02 WET07 NNC14 OVP02 STU01 GUP01 NNC12 DAL01 WET04 WET03 CEK02 GUP02 BBS26 NNC15 NNC13 DAL02 EIU02 EIU06 WET02 BBS27 MGD01 EIU01 NNC17 DMR01 GUP08 WET06 WET01 MII02 SYB01 WET05 NSS01 SYB02 NNC16 DMR03 GUP03 GUP05 EIU04 SYB04 TAN02 MGD02 GUP09 GSD01 TAN01 MII01 EIU05 BBN01 COS01 DMR02 MII03 CMC06 MGD06 PIL04 TAN03 DEU03 BBN02 GSD02 CMC01 BBN03 BBN04 PIL01 CMC02 BRT01 DEU01 BBN05 CHC01 MGD03 MGD07 DEU02 BRT02 BRT04 MGD05 BBN06 CMC03 LSD01 GSD05 GSD06 BBN07 PIL02 BRT03 MGD04 PIL03 GSD03 MAC03 BBN12 CAR01 GID02 MAC01 BBN09 BBN10 CMC04 DEU04 BBN11 BBN14 CMC05 GAS01 LSD02 MAC02 SSD01 BBN08 BBN13 GID01 GSD04 CHC03 BBS03 SEQ14 FIN01 MGD08 FIN02 SSD02 CHC04 BBS02 BBS05 BBS01 GAS03 CER01 BBS04 MUL09 BBS09 BBS06 BBS07 FIN03 SEQ01 CAR02 GAS02 BBS10 STP06 CHC02 BBS08 CHC05 FIN04 MUL06 SEQ08 MUL10 MUL04 BBS11 GVD04 CER03 STP05 CHC07 BBS12 SEQ07 MUR02 CER02 BBS13 STP01 MUL08 SEQ09 STP02 SSD03 SEQ05 CHC06 CHC08 BBS14 SEQ04 YAL01 GVD02 MUL02 SEQ06 MUL03 BBS16 BRISBANE MUR01 GVD05 STP04 -

Central Kimberley 2

Central Kimberley 2 Central Kimberley 2 (CK2 – Hart subregion) GORDON GRAHAM AUGUST 2001 Subregional description and deciduous low open-woodland with sparse-tussock grasses. biodiversity values • Eucalyptus brevifolia (snappy gum) low open- woodland with Triodia bitextura hummock grasses Description and area +/- Enneapogon spp. (nineawn grass) short-tussock grasses or sometimes a grassland without trees. This is hilly to mountainous country with parallel siliceous ranges of Proterozoic sedimentary rocks with Dominant land use skeletal sandy soils supporting Triodia spp. hummock (see Appendix B, key b) grasses with scattered trees, and with earths on Proterozoic volcanics in valleys supporting ribbon grass (ix) Grazing – Native pastures (Chrysopogon spp.) with scattered trees. Open forests of (xi) UCL and Crown reserves river gum (Eucalyptus camaldulensis) and Pandanus spp. occur along drainage lines. The climate is dry hot tropical Continental Stress Class and sub-humid to semi-arid with summer rainfall. The subregion has a rugged topography dominated by The Continental Stress Class for CK2 is 5. Hart dolerite exposed along the eastern edge of the Kimberley Craton, where its basement members are Known special values in relation to landscape, folded and exposed. The basement rocks are volcanics, ecosystem, species and genetic values plutonics and sedimentary rocks. This is the driest part of Central Kimberley bioregion with an annual rainfall of Rare Features: 600 mm to 700 mm. The vegetation is primarily • The subregion is fox and rabbit free and essentially savannah woodland over Triodia spp. and/or bunch uninhabited. grasses. In this subregion are found the headwaters of the • Two of the Kimberley region’s major rivers originate Ord, Dunham and Fitzroy Rivers. -

Central Kimberley 1 (CK1 – Pentecost Subregion)

Central Kimberley 1 Central Kimberley 1 (CK1 – Pentecost subregion) GORDON GRAHAM AUGUST 2001 Subregional description and biodiversity bitextura (curly spinifex) and Sorghum spp. (sorghum) grasses. values • Eucalyptus grandifolia (large-leaved cabbage gum) +/- Eucalyptus greeniana (broad-leaved bloodwood) +/- Eucalyptus polycarpa (long-fruited bloodwood) Description and area low open-woodland with Triodia bitextura (curly spinifex) hummock grasses or Chrysopogon spp. This is hilly to mountainous country with parallel (ribbon grass) and Dichanthium spp. (blue grass) siliceous ranges of Proterozoic sedimentary rocks with tussock grasses. skeletal sandy soils supporting Triodia spp. hummock • Eucalyptus brevifolia (snappy gum) low open- grasses with scattered trees, and with earths on woodland with Triodia pungens (soft spinifex) Proterozoic volcanics in valleys supporting ribbon grass and/or Triodia bitextura (curly spinifex) hummock (Chrysopogon spp.) with scattered trees. Open forests of grasses and/or tussock grasses. river red gum (Eucalyptus camaldulensis) and Pandanus • Eucalyptus brevifolia (snappy gum) low open- spp. occur along drainage lines. The climate is dry hot woodland with Triodia bitextura (curly spinifex) tropical and sub-humid to semi-arid with summer hummock grasses +/- Enneapogon spp. (nine-awn rainfall. grass) short-tussock grasses or sometimes a grassland without trees. The Pentecost subregion is predominantly middle Pentecosts sandstone, with King Leopold and Warton sandstone ranges along its southern peripheries. Large Dominant land use areas are mantled by Cainozoic soils. There is moderate (see Appendix B, key b) dissection by several rivers (Durack, Chamberlain and Fitzroy). This is the true central Kimberley. Average (ix) Grazing – Native pastures annual rainfall ranges from 750 mm to 1000 mm. The (xi) UCL and Crown reserves dominant vegetation is savannah woodlands of eucalypts over Triodia spp. -

Flora and Vegetation Communities of Selected Islands Off the Kimberley Coast of Western Australia

RECORDS OF THE WESTERN AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM 81 205–244 (2014) DOI: 10.18195/issn.0313-122x.81.2014.205-244 SUPPLEMENT Flora and vegetation communities of selected islands off the Kimberley coast of Western Australia M.N. Lyons1*, G.J. Keighery1, L.A. Gibson2 and T. Handasyde3 1 Department of Parks and Wildlife, Science and Conservation Division, Keiran McNamara Conservation Science Centre, Locked Bag 104, Bentley Delivery Centre, Western Australia 6983, Australia. 2 Department of Parks and Wildlife, Science and Conservation Division, PO Box 51, Wanneroo, Western Australia 6946, Australia. 3 Department of Parks and Wildlife, Science and Conservation Division, PO Box 942, Kununurra, Western Australia 6743, Australia. * Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT – A systematic survey of fl ora and fl oristic communities was undertaken on 24 selected inshore islands off the Northern Kimberley (NK) coast between 2007 and 2010. One hundred and thirty seven 50 x 50 m quadrats were sampled for fl oristics and surface soils, and site attributes recorded. Quadrat sampling was supplemented by general collecting to further document the fl oristics of major substrates and habitats of each island. We recorded 1005 taxa from the surveyed islands, of which, 403 taxa were new records for the collective islands of the NK bioregion. Based on existing Western Australian Herbarium collections and current survey records, the fl ora recorded from the islands represents approximately 49 percent of the NK bioregion fl ora. A total of 57 taxa of conservation signifi cance were recorded from the surveyed islands. Few taxa appear to be restricted to islands. -

Volume 5 Pt 3

Conservation Science W. Aust. 8 (3) : 259–275 (2013) Weedy native plants in Western Australia: an annotated checklist GREG KEIGHERY Science Division, Department of Environment and Conservation, Locked Bag 104, Bentley Delivery Centre, Western Australia, 6983. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT An annotated checklist of 78 Western Australian native plant species with naturalized populations in Western Australia is presented. Information on natural and weedy distributions, habitat and establishment is presented for each species, along with voucher specimen details. Further information is provided on doubtfully naturalized species, species contributing to disruption of genetic integrity, and species of uncertain occurrence status. Keywords: checklist, naturalised Western Australian vascular plants INTRODUCTION Herbaria 2012), and regional distributions follow IBRA 7 Regions of Western Australia (Department of Any plant outside the checks and balances of its natural Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and habitat can potentially be a weed. Western Australian native Community 2012). Natural distributions were sourced species are no exception and some are already serious weeds from the revisions and studies cited or from Florabase of the natural environment (Keighery 2002). With and the Australian Virtual Herbarium. increasing attempts to restore, rehabilitate and revegetate disturbed land in Western Australia, it is vital that we understand the natural distribution and ecology of our RESULTS AND DISCUSSION native flora. This enables the use of local provenance material that should minimize the actual and potential Our understanding of the distribution and ecology of introduction of potentially damaging weedy taxa. This many native species has improved greatly over the past paper seeks to list known weedy native species and provide 50 years. -

Tropical Savannas

© The Pew Environment Group Authors: Carol Booth & Barry Traill Published 2008 Cover photo: By Kerry Trapnell, McIllwraith Range, Cape York Peninsula For further information on this study, contact: Dr. Barry Traill, Director, Wild Australia Program, Pew Environment Group, 2 Treehaven Way, Maleny Qld. Australia 4552 Email: [email protected] CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................... 9 AIMS OF THIS PAPER ................................................................................................................................................ 9 ORIGINS & AIMS OF THE WILD AUSTRALIA PROGRAM .................................................................................................... 9 PROTECTION OF LARGE NATURAL AREAS .................................................................................................................... 11 Gaps and ommissions ................................................................................................................................... 12 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .............................................................................................................................................. 12 METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................................................................. 13 SELECTION OF FOCUS AREAS ....................................................................................................................................