Relations Between English Settlers and Indians in 17Th Century New

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Course Outline of Record Los Medanos College 2700 East Leland Road Pittsburg CA 94565 (925) 439-2181

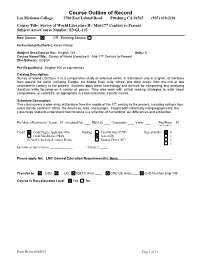

Course Outline of Record Los Medanos College 2700 East Leland Road Pittsburg CA 94565 (925) 439-2181 Course Title: Survey of World Literature II: Mid-17th Century to Present Subject Area/Course Number: ENGL-145 New Course OR Existing Course Instructor(s)/Author(s): Karen Nakaji Subject Area/Course No.: English 145 Units: 3 Course Name/Title: Survey of World Literature II: Mid-17th Century to Present Discipline(s): English Pre-Requisite(s): English 100 or equivalency Catalog Description: Survey of World Literature II is a comparative study of selected works, in translation and in English, of literature from around the world, including Europe, the Middle East, Asia, Africa, and other areas, from the mid or late seventeenth century to the present. Students apply basic terminology and devices for interpreting and analyzing literature while focusing on a variety of genres. They also work with critical reading strategies to write about comparisons, or contrasts, as appropriate in a baccalaureate, transfer course. Schedule Description: This class covers a wide array of literature from the middle of the 17th century to the present, including authors from every literate continent: Africa, the Americas, Asia, and Europe. Taught both historically and geographically, the class helps students understand how literature is a reflection of humankind, our differences and similarities. Hrs/Mode of Instruction: Lecture: 54 Scheduled Lab: ____ HBA Lab: ____ Composition: ____ Activity: ____ Total Hours 54 (Total for course) Credit Credit Degree Applicable -

English Settlement Before the Mayhews: the “Pease Tradition”

151 Lagoon Pond Road Vineyard Haven, MA 02568 Formerly MVMUSEUM The Dukes County Intelligencer NOVEMBER 2018 VOLUME 59 Quarterly NO. 4 Martha’s Vineyard Museum’s Journal of Island History MVMUSEUM.ORG English settlement before the Mayhews: Edgartown The “Pease Tradition” from the Sea Revisited View from the deck of a sailing ship in Nantucket Sound, looking south toward Edgartown, around the American Revolution. The land would have looked much the same to the first English settlers in the early 1600s (from The Atlantic Neptune, 1777). On the Cover: A modern replica of the Godspeed, a typical English merchant sailing ship from the early 1600s (photo by Trader Doc Hogan). Also in this Issue: Place Names and Hidden Histories MVMUSEUM.ORG MVMUSEUM Cover, Vol. 59 No. 4.indd 1 1/23/19 8:19:04 AM MVM Membership Categories Details at mvmuseum.org/membership Basic ..............................................$55 Partner ........................................$150 Sustainer .....................................$250 Patron ..........................................$500 Benefactor................................$1,000 Basic membership includes one adult; higher levels include two adults. All levels include children through age 18. Full-time Island residents are eligible for discounted membership rates. Contact Teresa Kruszewski at 508-627-4441 x117. Traces Some past events offer the historians who study them an embarrassment of riches. The archives of a successful company or an influential US president can easily fill a building, and distilling them into an authoritative book can consume decades. Other events leave behind only the barest traces—scraps and fragments of records, fleeting references by contemporary observers, and shadows thrown on other events of the time—and can be reconstructed only with the aid of inference, imagination, and ingenuity. -

The Exchange of Body Parts in the Pequot War

meanes to "A knitt them togeather": The Exchange of Body Parts in the Pequot War Andrew Lipman was IN the early seventeenth century, when New England still very new, Indians and colonists exchanged many things: furs, beads, pots, cloth, scalps, hands, and heads. The first exchanges of body parts a came during the 1637 Pequot War, punitive campaign fought by English colonists and their native allies against the Pequot people. the war and other native Throughout Mohegans, Narragansetts, peoples one gave parts of slain Pequots to their English partners. At point deliv so eries of trophies were frequent that colonists stopped keeping track of to individual parts, referring instead the "still many Pequods' heads and Most accounts of the war hands" that "came almost daily." secondary as only mention trophies in passing, seeing them just another grisly were aspect of this notoriously violent conflict.1 But these incidents a in at the Andrew Lipman is graduate student the History Department were at a University of Pennsylvania. Earlier versions of this article presented graduate student conference at the McNeil Center for Early American Studies in October 2005 and the annual conference of the South Central Society for Eighteenth-Century comments Studies in February 2006. For their and encouragement, the author thanks James H. Merrell, David Murray, Daniel K. Richter, Peter Silver, Robert Blair St. sets George, and Michael Zuckerman, along with both of conference participants and two the anonymous readers for the William and Mary Quarterly. 1 to John Winthrop, The History ofNew England from 1630 1649, ed. James 1: Savage (1825; repr., New York, 1972), 237 ("still many Pequods' heads"); John Mason, A Brief History of the Pequot War: Especially Of the memorable Taking of their Fort atMistick in Connecticut In 1637 (Boston, 1736), 17 ("came almost daily"). -

On-Site Historical Reenactment As Historiographic Operation at Plimoth Plantation

Fall2002 107 Recreation and Re-Creation: On-Site Historical Reenactment as Historiographic Operation at Plimoth Plantation Scott Magelssen Plimoth Plantation, a Massachusetts living history museum depicting the year 1627 in Plymouth Colony, advertises itself as a place where "history comes alive." The site uses costumed Pilgrims, who speak to visitors in a first-person presentvoice, in order to create a total living environment. Reenactment practices like this offer possibilities to teach history in a dynamic manner by immersing visitors in a space that allows them to suspend disbelief and encounter museum exhibits on an affective level. However, whether or not history actually "comes alive"at Plimoth Plantation needs to be addressed, especially in the face of new or postmodem historiography. No longer is it so simple to say the past can "come alive," given that in the last thirty years it has been shown that the "past" is contestable. A case in point, I argue, is the portrayal of Wampanoag Natives at Plimoth Plantation's "Hobbamock's Homesite." Here, the Native Wampanoag Interpretation Program refuses tojoin their Pilgrim counterparts in using first person interpretation, choosing instead to address visitors in their own voices. For the Native Interpreters, speaking in seventeenth-century voices would disallow presentationoftheir own accounts ofthe way colonists treated native peoples after 1627. Yet, from what I have learned in recent interviews with Plimoth's Public Relations Department, plans are underway to address the disparity in interpretive modes between the Pilgrim Village and Hobbamock's Homesite by introducing first person programming in the latter. I Coming from a theatre history and theory background, and looking back on three years of research at Plimoth and other living history museums, I would like to trouble this attempt to smooth over the differences between the two sites. -

Winslows: Pilgrims, Patrons, and Portraits

Copyright, The President and Trustees of Bowdoin College Brunswick, Maine 1974 PILGRIMS, PATRONS AND PORTRAITS A joint exhibition at Bowdoin College Museum of Art and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Organized by Bowdoin College Museum of Art Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2015 https://archive.org/details/winslowspilgrimsOObowd Introduction Boston has patronized many painters. One of the earhest was Augustine Clemens, who began painting in Reading, England, in 1623. He came to Boston in 1638 and probably did the portrait of Dr. John Clarke, now at Harvard Medical School, about 1664.' His son, Samuel, was a member of the next generation of Boston painters which also included John Foster and Thomas Smith. Foster, a Harvard graduate and printer, may have painted the portraits of John Davenport, John Wheelwright and Increase Mather. Smith was commis- sioned to paint the President of Harvard in 1683.^ While this portrait has been lost, Smith's own self-portrait is still extant. When the eighteenth century opened, a substantial number of pictures were painted in Boston. The artists of this period practiced a more academic style and show foreign training but very few are recorded by name. Perhaps various English artists traveled here, painted for a time and returned without leaving a written record of their trips. These artists are known only by their pictures and their identity is defined by the names of the sitters. Two of the most notable in Boston are the Pierpont Limner and the Pollard Limner. These paint- ers worked at the same time the so-called Patroon painters of New York flourished. -

A Matter of Truth

A MATTER OF TRUTH The Struggle for African Heritage & Indigenous People Equal Rights in Providence, Rhode Island (1620-2020) Cover images: African Mariner, oil on canvass. courtesy of Christian McBurney Collection. American Indian (Ninigret), portrait, oil on canvas by Charles Osgood, 1837-1838, courtesy of Massachusetts Historical Society Title page images: Thomas Howland by John Blanchard. 1895, courtesy of Rhode Island Historical Society Christiana Carteaux Bannister, painted by her husband, Edward Mitchell Bannister. From the Rhode Island School of Design collection. © 2021 Rhode Island Black Heritage Society & 1696 Heritage Group Designed by 1696 Heritage Group For information about Rhode Island Black Heritage Society, please write to: Rhode Island Black Heritage Society PO Box 4238, Middletown, RI 02842 RIBlackHeritage.org Printed in the United States of America. A MATTER OF TRUTH The Struggle For African Heritage & Indigenous People Equal Rights in Providence, Rhode Island (1620-2020) The examination and documentation of the role of the City of Providence and State of Rhode Island in supporting a “Separate and Unequal” existence for African heritage, Indigenous, and people of color. This work was developed with the Mayor’s African American Ambassador Group, which meets weekly and serves as a direct line of communication between the community and the Administration. What originally began with faith leaders as a means to ensure equitable access to COVID-19-related care and resources has since expanded, establishing subcommittees focused on recommending strategies to increase equity citywide. By the Rhode Island Black Heritage Society and 1696 Heritage Group Research and writing - Keith W. Stokes and Theresa Guzmán Stokes Editor - W. -

London and Middlesex in the 1660S Introduction: the Early Modern

London and Middlesex in the 1660s Introduction: The early modern metropolis first comes into sharp visual focus in the middle of the seventeenth century, for a number of reasons. Most obviously this is the period when Wenceslas Hollar was depicting the capital and its inhabitants, with views of Covent Garden, the Royal Exchange, London women, his great panoramic view from Milbank to Greenwich, and his vignettes of palaces and country-houses in the environs. His oblique birds-eye map- view of Drury Lane and Covent Garden around 1660 offers an extraordinary level of detail of the streetscape and architectural texture of the area, from great mansions to modest cottages, while the map of the burnt city he issued shortly after the Fire of 1666 preserves a record of the medieval street-plan, dotted with churches and public buildings, as well as giving a glimpse of the unburned areas.1 Although the Fire destroyed most of the historic core of London, the need to rebuild the burnt city generated numerous surveys, plans, and written accounts of individual properties, and stimulated the production of a new and large-scale map of the city in 1676.2 Late-seventeenth-century maps of London included more of the spreading suburbs, east and west, while outer Middlesex was covered in rather less detail by county maps such as that of 1667, published by Richard Blome [Fig. 5]. In addition to the visual representations of mid-seventeenth-century London, a wider range of documentary sources for the city and its people becomes available to the historian. -

CAPE HENRY MEMORIAL VIRGINIA the Settlers Reached Jamestown

CAPE HENRY MEMORIAL VIRGINIA the settlers reached Jamestown. In the interim, Captain Newport remained in charge. The colonists who established Jamestown On April 27 a second party was put ashore. They spent some time "recreating themselves" made their first landing in Virginia and pushed hard on assembling a small boat— a "shallop"—to aid in exploration. The men made short marches in the vicinity of the cape and at Cape Henry on April 26, 1607 enjoyed some oysters found roasting over an Indian campfire. The next day the "shallop" was launched, and The memorial cross, erected in 1935. exploration in the lower reaches of the Chesa peake Bay followed immediately. The colonists At Cape Henry, Englishmen staged Scene scouted by land also, and reported: "We past Approaching Chesapeake Bay from the south through excellent ground full of Flowers of divers I, Act I of their successful drama of east, the Virginia Company expedition made kinds and colours, and as goodly trees as I have conquering the American wilderness. their landfall at Cape Henry, the southernmost seene, as Cedar, Cipresse, and other kinds . Here, "about foure a clocke in the morning" promontory of that body of water. Capt. fine and beautiful Strawberries, foure time Christopher Newport, in command of the fleet, bigger and better than ours in England." on April 26,1607, some 105 sea-weary brought his ships to anchor in protected waters colonists "descried the Land of Virginia." just inside the bay. He and Edward Maria On April 29 the colonists, possibly using Wingfield (destined to be the first president of English oak already fashioned for the purpose, They had left England late in 1606 and the colony), Bartholomew Gosnold, and "30 others" "set up a Crosse at Chesupioc Bay, and named spent the greater part of the next 5 months made up the initial party that went ashore to that place Cape Henry" for Henry, Prince of in the strict confines of three small ships, see the "faire meddowes," "Fresh-waters," and Wales, oldest son of King James I. -

A Jamestown Timeline

A Jamestown Timeline Christopher Columbus never reached the shores of the North American Continent, but European explorers learned three things from him: there was someplace to go, there was a way to get there, and most importantly, there was a way to get back. Thus began the European exploration of what they referred to as the “New World”. The following timeline details important events in the establishment of the fi rst permanent English settlement in America – Jamestown, Virginia. PRELIMINARY EVENTS 1570s Spanish Jesuits set up an Indian mission on the York River in Virginia. They were killed by the Indians, and the mission was abandoned. Wahunsonacock (Chief Powhatan) inherited a chiefdom of six tribes on the upper James and middle York Rivers. By 1607, he had conquered about 25 other tribes. 1585-1590 Three separate voyages sent English settlers to Roanoke, Virginia (now North Carolina). On the last voyage, John White could not locate the “lost” settlers. 1602 Captain Bartholomew Gosnold explored New England, naming some areas near and including Martha’s Vineyard. 1603 Queen Elizabeth I died; James VI of Scotland became James I of England. EARLY SETTLEMENT YEARS 1606, April James I of England granted a charter to the Virginia Company to establish colonies in Virginia. The charter named two branches of the Company, the Virginia Company of London and the Virginia Company of Plymouth. 1606, December 20 Three ships – Susan Constant, Godspeed, and Discovery – left London with 105 men and boys to establish a colony in Virginia between 34 and 41 degrees latitude. 1607, April 26 The three ships sighted the land of Virginia, landed at Cape Henry (present day Virginia Beach) and were attacked by Indians. -

Aquidneck Island's Reluctant Revolutionaries, 16'\8- I 660

Rhode Island History Pubhshed by Th e Rhod e bland Hrstoncal Society, 110 Benevolent St reet, Volume 44, Number I 1985 Providence, Rhode Island, 0 1~, and February prmted by a grant from th e Stale of Rhode Island and Providence Plamauons Contents Issued Ouanerl y at Providence, Rhode Island, ~bruary, May, Au~m , and Freedom of Religion in Rhode Island : November. Secoed class poet age paId al Prcvrdence, Rhode Island Aquidneck Island's Reluctant Revolutionaries, 16'\8- I 660 Kafl Encson , presIdent S HEI LA L. S KEMP Alden M. Anderson, VIet presIdent Mrs Edwin G FI!I.chel, vtce preudenr M . Rachtl Cunha, seatrory From Watt to Allen to Corliss: Stephen Wllhams. treasurer Arnold Friedman, Q.u ur<lnt secretary One Hundred Years of Letting Off Steam n u ow\ O f THl ~n TY 19 Catl Bndenbaugh C H AR LES H O F f M A N N AND TESS HOFFMANN Sydney V James Am cmeree f . Dowrun,; Richard K Showman Book Reviews 28 I'UIIU CAT!O~ S COM!I4lTT l l Leonard I. Levm, chairmen Henry L. P. Beckwith, II. loc i Cohen NOl1lUn flerlOlJ: Raben Allen Greene Pamtla Kennedy Alan Simpson William McKenzIe Woodward STAff Glenn Warren LaFamasie, ed itor (on leave ] Ionathan Srsk, vUlI1ng edltot Maureen Taylo r, tncusre I'drlOt Leonard I. Levin, copy editor [can LeGwin , designer Barbara M. Passman, ednonat Q8.lislant The Rhode Island Hrsto rrcal Socrerv assumes no respcnsrbihrv for the opinions 01 ccntnbutors . Cl l9 8 j by The Rhode Island Hrstcncal Society Thi s late nmeteensh-centurv illustration presents a romanticized image of Anne Hutchinson 's mal during the AntJnomian controversy. -

"In the Pilgrim Way" by Linda Ashley, A

In the Pilgrim Way The First Congregational Church, Marshfield, Massachusetts 1640-2000 Linda Ramsey Ashley Marshfield, Massachusetts 2001 BIBLIO-tec Cataloging in Publication Ashley, Linda Ramsey [1941-] In the pilgrim way: history of the First Congregational Church, Marshfield, MA. Bibliography Includes index. 1. Marshfield, Massachusetts – history – churches. I. Ashley, Linda R. F74. 2001 974.44 Manufactured in the United States. First Edition. © Linda R. Ashley, Marshfield, MA 2001 Printing and binding by Powderhorn Press, Plymouth, MA ii Table of Contents The 1600’s 1 Plimoth Colony 3 Establishment of Green’s Harbor 4 Establishment of First Parish Church 5 Ministry of Richard Blinman 8 Ministry of Edward Bulkley 10 Ministry of Samuel Arnold 14 Ministry of Edward Tompson 20 The 1700’s 27 Ministry of James Gardner 27 Ministry of Samuel Hill 29 Ministry of Joseph Green 31 Ministry of Thomas Brown 34 Ministry of William Shaw 37 The 1800’s 43 Ministry of Martin Parris 43 Ministry of Seneca White 46 Ministry of Ebenezer Alden 54 Ministry of Richard Whidden 61 Ministry of Isaac Prior 63 Ministry of Frederic Manning 64 The 1900’s 67 Ministry of Burton Lucas 67 Ministry of Daniel Gross 68 Ministry of Charles Peck 69 Ministry of Walter Squires 71 Ministry of J. Sherman Gove 72 Ministry of George W. Zartman 73 Ministry of William L. Halladay 74 Ministry of J. Stanley Bellinger 75 Ministry of Edwin C. Field 76 Ministry of George D. Hallowell 77 Ministry of Vaughn Shedd 82 Ministry of William J. Cox 85 Ministry of Robert H. Jackson 87 Other Topics Colonial Churches of New England 92 United Church of Christ 93 Church Buildings or Meetinghouses 96 The Parsonages 114 Organizations 123 Sunday School and Youth 129 Music 134 Current Officers, Board, & Committees 139 Gifts to the Church 141 Memorial Funds 143 iii The Centuries The centuries look down from snowy heights Upon the plains below, While man looks upward toward those beacon lights Of long ago. -

(King Philip's War), 1675-1676 Dissertation Presented in Partial

Connecticut Unscathed: Victory in The Great Narragansett War (King Philip’s War), 1675-1676 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Major Jason W. Warren, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: John F. Guilmartin Jr., Advisor Alan Gallay, Kristen Gremillion Peter Mansoor, Geoffrey Parker Copyright by Jason W. Warren 2011 Abstract King Philip’s War (1675-1676) was one of the bloodiest per capita in American history. Although hostile native groups damaged much of New England, Connecticut emerged unscathed from the conflict. Connecticut’s role has been obscured by historians’ focus on the disasters in the other colonies as well as a misplaced emphasis on “King Philip,” a chief sachem of the Wampanoag groups. Although Philip formed the initial hostile coalition and served as an important leader, he was later overshadowed by other sachems of stronger native groups such as the Narragansetts. Viewing the conflict through the lens of a ‘Great Narragansett War’ brings Connecticut’s role more clearly into focus, and indeed enables a more accurate narrative for the conflict. Connecticut achieved success where other colonies failed by establishing a policy of moderation towards the native groups living within its borders. This relationship set the stage for successful military operations. Local native groups, whether allied or neutral did not assist hostile Indians, denying them the critical intelligence necessary to coordinate attacks on Connecticut towns. The English colonists convinced allied Mohegan, Pequot, and Western Niantic warriors to support their military operations, giving Connecticut forces a decisive advantage in the field.