Rhode Island History Winter/Spring 2009 Volume 67, Number 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revolutionary War and an Amsterdam Privy: the Remarkable Background of a Rhode Island Ship Token Ranjith M

Northeast Historical Archaeology Volume 40 Article 7 2011 Revolutionary War and an Amsterdam Privy: The Remarkable Background of a Rhode Island Ship Token Ranjith M. Jayasena Follow this and additional works at: http://orb.binghamton.edu/neha Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Jayasena, Ranjith M. (2011) "Revolutionary War and an Amsterdam Privy: The Remarkable Background of a Rhode Island Ship Token," Northeast Historical Archaeology: Vol. 40 40, Article 7. https://doi.org/10.22191/neha/vol40/iss1/7 Available at: http://orb.binghamton.edu/neha/vol40/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). It has been accepted for inclusion in Northeast Historical Archaeology by an authorized editor of The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). For more information, please contact [email protected]. Northeast Historical Archaeology/Vol. 40, 2011 123 Revolutionary War and an Amsterdam Privy: The Remarkable Background of a Rhode Island Ship Token Ranjith M. Jayasena In 2008 the City of Amsterdam Office for Monuments & Archaeology (BMA) excavated a remarkable find from a late 18th-century privy in Amsterdam’s city centre that can be directly linked to the American Revolutionary War, a 1779 Rhode Island Ship Token. Approximately twenty five examples of this token are known worldwide, but none of them come from an archaeological context. From this Amsterdam find one can examine these tokens from an entirely new aspect, namely the socio-economic context of the owner as well as the period in which the token was used. The Rhode Island Ship Token was a British propaganda piece ridiculing the weakness of the Americans in 1778 and distributed in the Netherlands to create negative views of the American revolutionaries to discourage the Dutch from intervening in the Anglo-American conflict. -

An Inclusive Commonwealth This Year’S Theme Celebrates the Diversity of the Commonwealth, Which Is Made up of More Than Two Billion People

An Inclusive Commonwealth This year’s theme celebrates the diversity of the Commonwealth, which is made up of more than two billion people. Every one of them is different, and each of them has something unique to offer. The Commonwealth Charter asserts that everyone is equal and deserves to be treated fairly, whether they are rich or poor, without regard to their race, age, gender, belief or other identity. The Commonwealth builds a better world by including and respecting everybody and the richness of their personalities. Commonwealth Day is 14 March 2016 thecommonwealth.org/inclusivecommonwealth #inclusivecommonwealth 1 4 27 50 52 32 7 3 23 9 26 11 30 43 8 39 2 6 53 15 29 45 47 18 36 28 24 10 41 24 14 37 35 40 25 20 The Commonwealth is made up of 12 49 38 48 53 countries around the world 5 22 42 19 31 16 46 13 The Commonwealth is a voluntary association of 51 34 independent countries spread over every continent 33 and ocean. Its two billion people, who account for nearly 44 21 30 per cent of the world’s population, are in Africa, Asia, the Caribbean and Americas, Europe and the Pacific. 17 They are of many faiths, races, languages and cultures. Commonwealth countries Can you name the Commonwealth countries? ANTIGUA AND NAURU BARBUDA NEW ZEALAND AUSTRALIA NIGERIA BAHAMAS CAPITAL COUNTRY CAPITAL COUNTRY CAPITAL COUNTRY CAPITAL COUNTRY PAKISTAN BANGLADESH PAPUA NEW GUINEA 1 OTTAWA 15 FREETOWN 28 MALÉ 42 PORT VILA BARBADOS RWANDA BELIZE 2 KINGSTOWN 16 PORT LOUIS 29 ACCRA 43 CASTRIES ST KITTS AND NEVIS BOTSWANA SAINT LUCIA 3 NEW DELHI 17 -

A Matter of Truth

A MATTER OF TRUTH The Struggle for African Heritage & Indigenous People Equal Rights in Providence, Rhode Island (1620-2020) Cover images: African Mariner, oil on canvass. courtesy of Christian McBurney Collection. American Indian (Ninigret), portrait, oil on canvas by Charles Osgood, 1837-1838, courtesy of Massachusetts Historical Society Title page images: Thomas Howland by John Blanchard. 1895, courtesy of Rhode Island Historical Society Christiana Carteaux Bannister, painted by her husband, Edward Mitchell Bannister. From the Rhode Island School of Design collection. © 2021 Rhode Island Black Heritage Society & 1696 Heritage Group Designed by 1696 Heritage Group For information about Rhode Island Black Heritage Society, please write to: Rhode Island Black Heritage Society PO Box 4238, Middletown, RI 02842 RIBlackHeritage.org Printed in the United States of America. A MATTER OF TRUTH The Struggle For African Heritage & Indigenous People Equal Rights in Providence, Rhode Island (1620-2020) The examination and documentation of the role of the City of Providence and State of Rhode Island in supporting a “Separate and Unequal” existence for African heritage, Indigenous, and people of color. This work was developed with the Mayor’s African American Ambassador Group, which meets weekly and serves as a direct line of communication between the community and the Administration. What originally began with faith leaders as a means to ensure equitable access to COVID-19-related care and resources has since expanded, establishing subcommittees focused on recommending strategies to increase equity citywide. By the Rhode Island Black Heritage Society and 1696 Heritage Group Research and writing - Keith W. Stokes and Theresa Guzmán Stokes Editor - W. -

What Do These Things Mean?

What Do These Things Mean? ms.,71 IRE 47===16, , 44(-4-62.7; N 141S PRAISE IN THE S LA • .7. AND Vol 4—No 7] Port-of-Spain, July, 1906. [Price 3 Cents ..VECE2 ME=MIMM. 0 0 0 -0 0oc' 9 0, 0 ORPHANAGE, KARMATAR, INDIA. c-3c, c3c, c-3c, cS4ca oho 4, 4. 4:?Q pi o ao cler, c-3c, <lc> cy7 cso c•-sc, c-sc, oho cz:sc, ii THE CARIBBEAN WATCHMAN ••••••• •••••.• • ••••••• •••••,•••••. • ....•••••••••••••••....• "..,..•••...•Croo•volg;#•••••••,•••••• •••0•••••'•00,00•.~. • ••••••,..0 • 0.0 • ottt• ••••••• • •••• • ••••. ••••...• ta, •••,.. • • O ( )( )( ) PUBLISHED MONTHLY BY THE Publishers' Notes International Tract Society. Registered as a newspaper at Port-of-Spain. 0 ) ( ) Trinidad. 8. A. Wellman.. .. .. Business Manager We are just in receipt of a new stock of the following excellent Terms of Subscription. 'volumes, well known and admired by the book-loving portion of Per Year, post-paid, inert. our readers. Steps to Christ in both cloth and paper bindings at Six Months • Acts, 5o and 25 cents respectively; Bible Readings, marble at $2.25; Great Controversy, marble at $2.25 ; Gospel Primer, board at 25cts; To Our Patrons Paradise Home, board 25 cents ; Coming King, cloth at $1, and Please be careful to write all names of persomr and places plainly. Heralds of the Morning, cloth at $1.50. Other volumes too numer- Send Money by Post Office Money Order. of ous to mention-. The old standbys are in stock. Bank Draft on New York or London. Orders and Drafts should be made payable to S. A. Wellman. When Subscriptions Expire no more papers are The past month, with the aid of our new machinery, we have sent to the party except by special arrangement. -

David Library of the American Revolution Guide to Microform Holdings

DAVID LIBRARY OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION GUIDE TO MICROFORM HOLDINGS Adams, Samuel (1722-1803). Papers, 1635-1826. 5 reels. Includes papers and correspondence of the Massachusetts patriot, organizer of resistance to British rule, signer of the Declaration of Independence, and Revolutionary statesman. Includes calendar on final reel. Originals are in the New York Public Library. [FILM 674] Adams, Dr. Samuel. Diaries, 1758-1819. 2 reels. Diaries, letters, and anatomy commonplace book of the Massachusetts physician who served in the Continental Artillery during the Revolution. Originals are in the New York Public Library. [FILM 380] Alexander, William (1726-1783). Selected papers, 1767-1782. 1 reel. William Alexander, also known as “Lord Sterling,” first served as colonel of the 1st NJ Regiment. In 1776 he was appointed brigadier general and took command of the defense of New York City as well as serving as an advisor to General Washington. He was promoted to major- general in 1777. Papers consist of correspondence, military orders and reports, and bulletins to the Continental Congress. Originals are in the New York Historical Society. [FILM 404] American Army (Continental, militia, volunteer). See: United States. National Archives. Compiled Service Records of Soldiers Who Served in the American Army During the Revolutionary War. United States. National Archives. General Index to the Compiled Military Service Records of Revolutionary War Soldiers. United States. National Archives. Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. United States. National Archives. Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty and Warrant Application Files. United States. National Archives. Revolutionary War Rolls. 1775-1783. American Periodicals Series I. 33 reels. Accompanied by a guide. -

Sails of Glory Battle for the Seas a Sails of Glory Campaign

Sails Of Glory Battle for the Seas A Sails of Glory Campaign Time Sometime during the Napoleonic Wars 1803-1805. Info about the Campaign After Napoleon had won many great victories on land in Europe, and crushed every country in battle. France was the dominating power in Europe on land and the English were masters of the sea. Behind their wooden wall of ships, they were relatively safe from any invasion force. Napoleon wanted to change this and invade England. In March 1802 a peace treaty was signed between France and England in Amiens, France. But both countries were irritated and angry with each other’s actions in the aftermath of the peace treaty, and it was an uneasy peace. And after some diplomatic quarrels England declared war on France again in May 1803. After war broke out again, Napoleon started preparation for invasion of England – but to have success, he needed to take out the English fleet that protected the English Channel. From 1803 to 1805 a new army of 150 000-200,000 men, known as the Armée des côtes de l'Océan (Army of the Ocean Coasts) or the Armée d'Angleterre (Army of England), was gathered and trained at camps at Boulogne, Bruges and Montreuil. A large "National Flotilla" of invasion barges was built in Channel ports along the coasts of France and the Netherlands. A fleet of nearly 2000 craft. At the same time he made plans with the Spanish to assemble a large fleet, which was strong enough to challenge the English Navy, and make it possible for Napoleon to invade England. -

Aquidneck Island's Reluctant Revolutionaries, 16'\8- I 660

Rhode Island History Pubhshed by Th e Rhod e bland Hrstoncal Society, 110 Benevolent St reet, Volume 44, Number I 1985 Providence, Rhode Island, 0 1~, and February prmted by a grant from th e Stale of Rhode Island and Providence Plamauons Contents Issued Ouanerl y at Providence, Rhode Island, ~bruary, May, Au~m , and Freedom of Religion in Rhode Island : November. Secoed class poet age paId al Prcvrdence, Rhode Island Aquidneck Island's Reluctant Revolutionaries, 16'\8- I 660 Kafl Encson , presIdent S HEI LA L. S KEMP Alden M. Anderson, VIet presIdent Mrs Edwin G FI!I.chel, vtce preudenr M . Rachtl Cunha, seatrory From Watt to Allen to Corliss: Stephen Wllhams. treasurer Arnold Friedman, Q.u ur<lnt secretary One Hundred Years of Letting Off Steam n u ow\ O f THl ~n TY 19 Catl Bndenbaugh C H AR LES H O F f M A N N AND TESS HOFFMANN Sydney V James Am cmeree f . Dowrun,; Richard K Showman Book Reviews 28 I'UIIU CAT!O~ S COM!I4lTT l l Leonard I. Levm, chairmen Henry L. P. Beckwith, II. loc i Cohen NOl1lUn flerlOlJ: Raben Allen Greene Pamtla Kennedy Alan Simpson William McKenzIe Woodward STAff Glenn Warren LaFamasie, ed itor (on leave ] Ionathan Srsk, vUlI1ng edltot Maureen Taylo r, tncusre I'drlOt Leonard I. Levin, copy editor [can LeGwin , designer Barbara M. Passman, ednonat Q8.lislant The Rhode Island Hrsto rrcal Socrerv assumes no respcnsrbihrv for the opinions 01 ccntnbutors . Cl l9 8 j by The Rhode Island Hrstcncal Society Thi s late nmeteensh-centurv illustration presents a romanticized image of Anne Hutchinson 's mal during the AntJnomian controversy. -

Organization Lloyd Albert AAA Northeast Thomas Ardito

First Name: Last Name: Organization Lloyd Albert AAA Northeast Thomas Ardito Aquidneck Island Planning Commission William Ashworth VHB Kate Aubin Lisa Aurecchia Woonasquatucket River Watershed Council Scott Avedisian City of Warwick Robert Azar Providence Planning & Development Paul Bannon BETA Group, Inc. Anthony Baro E2SOL LLC Dan Baudouin The Providence Foundation Ingrid Bentsen Matthew Blair Annette Bourne Grow Smart RI Laura Bozzi Karen Bradbury Office of Senator Sheldon Whitehouse Meredith Brady Rhode Island Department of Transportation Peter Brassard Todd Brayton Bryant Associates, Inc. Brett Broesder Edward Brown RIPTA James Brown Bryant University Kenneth Burke RI Water Resources Board Liza Burkin Bike Newport Linsey Callaghan Rhode Island Statewide Planning Program Allison Callahan Rhode Island Deparment of Environmental Management Chris Capizzo Shechtman Halperin Savage, LLP Lauren Carson State Representative Taber Caton Searle Design Group Josh Catone James Celenza RICOSH Buff Chace Cornish Associates, LP Nathaniel Chace Cornish Associates, LP Sandra Clarey McMahon Associates Molly Clark American Lung Association in Rhode Island Abel Collins Coalition for Transportation Choices Dylan Conley Millennial Professional Group of Rhode Island Sam Coren Ellen Cynar City of Providence- Healthy Communities Jeff Davis Rhode Island Division of Planning Stephen Devine RIDOT Alberta Devor James Diossa City of Central Falls Steve Durkee Cornish Assoc. Arthur Eddy Birchwood Design Group Jerry Elmer Conservation Law Foundation Jim Eng Rhode -

Jamestown, Rhode Island

Historic andArchitectural Resources ofJamestown, Rhode Island 1 Li *fl U fl It - .-*-,. -.- - - . ---... -S - Historic and Architectural Resources of Jamestown, Rhode Island Rhode Island Historical Preservation & Heritage Commission 1995 Historic and Architectural Resources ofJamestown, Rhode Island, is published by the Rhode Island Historical Preservation & Heritage Commission, which is the state historic preservation office, in cooperation with the Jamestown Historical Society. Preparation of this publication has been funded in part by the National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior. The contents and opinions herein, however, do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior. The Rhode Island Historical Preservation & Heritage Commission receives federal funds from the National Park Service. Regulations of the United States Department of the Interior strictly prohibit discrimination in departmental federally assisted programs on the basis of race, color, national origin, or handicap. Any person who believes that he or she has been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility operated by a recipient of federal assistance should write to: Director, Equal Opportunity Program, United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, P.O. Box 37127, Washington, D.C. 20013-7127. Cover East Fern’. Photograph c. 1890. Couriecy of Janiestown Historical Society. This view, looking north along tile shore, shows the steam feriy Conanicut leaving tile slip. From left to rig/It are tile Thorndike Hotel, Gardner house, Riverside, Bay View Hotel and tile Bay Voyage Inn. Only tile Bay Voyage Iiii suivives. Title Page: Beavertail Lighthouse, 1856, Beavertail Road. Tile light/louse tower at the southern tip of the island, the tallest offive buildings at this site, is a 52-foot-high stone structure. -

Collision Between Hms Relentless & Hms Vigilant

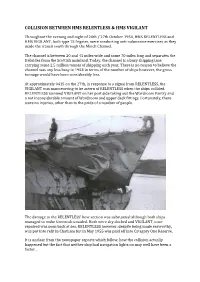

COLLISION BETWEEN HMS RELENTLESS & HMS VIGILANT Throughout the evening and night of 26th / 27th October 1954, HMS RELENTLESS and HMS VIGILANT, both type 15 frigates, were conducting anti-submarine exercises as they made the transit south through the Minch Channel. The channel is between 20 and 45 miles wide and some 70 miles long and separates the Hebrides from the Scottish mainland. Today, the channel is a busy shipping lane carrying some 2.5 million tonnes of shipping each year. There is no reason to believe the channel was any less busy in 1954 in terms of the number of ships however, the gross tonnage would have been considerably less. At approximately 0415 on the 27th, in response to a signal from RELENTLESS, the VIGILANT was manoeuvring to be astern of RELENTLESS when the ships collided. RELENTLESS rammed VIGILANT on her port side taking out the Wardroom Pantry and a not inconsiderable amount of Wardroom and upper deck fittings. Fortunately, there were no injuries, other than to the pride of a number of people. The damage to the RELENTLESS’ bow section was substantial although both ships managed to make Greenock unaided. Both were dry docked and VIGILANT, once repaired was soon back at sea. RELENTLESS however, despite being made seaworthy, was put into refit in Chatham but in May 1955 was paid off into Category One Reserve. It is unclear from the newspaper reports which follow, how the collision actually happened but the fact that neither ship had navigation lights on may well have been a factor... The Glasgow Herald, Saturday December 4th 1954. -

Cuban-American Developers Want a Say in Ambitious Havana Restoration

Vol. 11, No. 12 December 2003 www.cubanews.com In the News Despite Bacardi threat, Havana Club J-V GDP inches up enjoys booming rum sales in W. Europe Cuban officials say the island’s economy BY LARRY LUXNER 100 premium distilled spirits. “Demand has been exploding in Europe,” he grew by 2% in 2003 ........................Page 4 ’m just a humble rum merchant,” protests Alexandre Sirech as he sits in his cheerful, said, noting that total sales in the first 10 months Isunny office decorated with posters of 1950s of 2003 were 11% higher than the comparable Washington briefs Havana and shelves lined with liquor bottles of period in 2002. “If we keep up with this momen- OFAC devotes 17.5% of staff to embargo; every size, shape and brand imaginable. tum, we should rank in the top 40 very soon.” What makes this achievement really impres- Dennis Hays has new job .............Page 5 Of course, Sirech is joking. As director-general of Havana Club Interna- sive is that Havana Club has been able to score tional S.A., the 37-year-old Frenchman from Bor- these gains without selling a drop of rum in the Daiquiri diplomacy deaux — who speaks English like a Londoner United States, the world’s largest rum market. Florida-based Splash wins $500,000 deal and Spanish like a madrileño — presides over Sirech said that in order to prevent his bosses for frozen cocktail mixes ..............Page 7 what may be the biggest, most successful joint from violating the 1996 Helms-Burton Act and venture ever launched between foreign in- lesser manifestations of Washington’s 40-year- vestors and Cuba’s communist government. -

Loyalists in War, Americans in Peace: the Reintegration of the Loyalists, 1775-1800

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2008 LOYALISTS IN WAR, AMERICANS IN PEACE: THE REINTEGRATION OF THE LOYALISTS, 1775-1800 Aaron N. Coleman University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Coleman, Aaron N., "LOYALISTS IN WAR, AMERICANS IN PEACE: THE REINTEGRATION OF THE LOYALISTS, 1775-1800" (2008). University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations. 620. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_diss/620 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF DISSERATION Aaron N. Coleman The Graduate School University of Kentucky 2008 LOYALISTS IN WAR, AMERICANS IN PEACE: THE REINTEGRATION OF THE LOYALISTS, 1775-1800 _________________________________________________ ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION _________________________________________________ A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Kentucky By Aaron N. Coleman Lexington, Kentucky Director: Dr. Daniel Blake Smith, Professor of History Lexington, Kentucky 2008 Copyright © Aaron N. Coleman 2008 iv ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION LOYALISTS IN WAR, AMERICANS IN PEACE: THE REINTEGRATION OF THE LOYALISTS, 1775-1800 After the American Revolution a number of Loyalists, those colonial Americans who remained loyal to England during the War for Independence, did not relocate to the other dominions of the British Empire.