Introduction 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Suppression of Jewish Culture by the Soviet Union's Emigration

\\server05\productn\B\BIN\23-1\BIN104.txt unknown Seq: 1 18-JUL-05 11:26 A STRUGGLE TO PRESERVE ETHNIC IDENTITY: THE SUPPRESSION OF JEWISH CULTURE BY THE SOVIET UNION’S EMIGRATION POLICY BETWEEN 1945-1985 I. SOCIAL AND CULTURAL STATUS OF JEWS IN THE SOVIET SOCIETY BEFORE AND AFTER THE WAR .................. 159 R II. BEFORE THE BORDERS WERE CLOSED: SOVIET EMIGRATION POLICY UNDER STALIN (1945-1947) ......... 163 R III. CLOSING OF THE BORDER: CESSATION OF JEWISH EMIGRATION UNDER STALIN’S REGIME .................... 166 R IV. THE STRUGGLE CONTINUES: SOVIET EMIGRATION POLICY UNDER KHRUSHCHEV AND BREZHNEV .................... 168 R V. CONCLUSION .............................................. 174 R I. SOCIAL AND CULTURAL STATUS OF JEWS IN THE SOVIET SOCIETY BEFORE AND AFTER THE WAR Despite undergoing numerous revisions, neither the Soviet Constitu- tion nor the Soviet Criminal Code ever adopted any laws or regulations that openly or implicitly permitted persecution of or discrimination against members of any minority group.1 On the surface, the laws were always structured to promote and protect equality of rights and status for more than one hundred different ethnic groups. Since November 15, 1917, a resolution issued by the Second All-Russia Congress of the Sovi- ets called for the “revoking of all and every national and national-relig- ious privilege and restriction.”2 The Congress also expressly recognized “the right of the peoples of Russia to free self-determination up to seces- sion and the formation of an independent state.” Identical resolutions were later adopted by each of the 15 Soviet Republics. Furthermore, Article 124 of the 1936 (Stalin-revised) Constitution stated that “[f]reedom of religious worship and freedom of anti-religious propaganda is recognized for all citizens.” 3 1 See generally W.E. -

Questions to Russian Archives – Short

The Raoul Wallenberg Research Initiative RWI-70 Formal Request to the Russian Government and Archival Authorities on the Raoul Wallenberg Case Pending Questions about Documentation on the 1 Raoul Wallenberg Case in the Russian Archives Photo Credit: Raoul Wallenberg’s photo on a visa application he filed in June 1943 with the Hungarian Legation, Stockholm. Source: The Hungarian National Archives, Budapest. 1 This text is authored by Dr. Vadim Birstein and Susanne Berger. It is based on the paper by V. Birstein and S. Berger, entitled “Das Schicksal Raoul Wallenbergs – Die Wissenslücken.” Auf den Spuren Wallenbergs, Stefan Karner (Hg.). Innsbruck: StudienVerlag, 2015. S. 117-141; the English version of the paper with the title “The Fate of Raoul Wallenberg: Gaps in Our Current Knowledge” is available at http://www.vbirstein.com. Previously many of the questions cited in this document were raised in some form by various experts and researchers. Some have received partial answers, but not to the degree that they could be removed from this list of open questions. 1 I. FSB (Russian Federal Security Service) Archival Materials 1. Interrogation Registers and “Prisoner no. 7”2 1) The key question is: What happened to Raoul Wallenberg after his last known presence in Lubyanka Prison (also known as Inner Prison – the main investigation prison of the Soviet State Security Ministry, MGB, in Moscow) allegedly on March 11, 1947? At the time, Wallenberg was investigated by the 4th Department of the 3rd MGB Main Directorate (military counterintelligence); -

Download to View

The Mao Era in Objects Money (钱) Helen Wang, The British Museum & Felix Boecking, University of Edinburgh Summary In the early twentieth century, when the Communists gained territory, they set up revolutionary base areas (also known as soviets), and issued new coins and notes, using whatever expertise, supplies and technology were available. Like coins and banknotes all over the world, these played an important role in economic and financial life, and were also instrumental in conveying images of the new political authority. Since 1949, all regular banknotes in the People’s Republic of China have been issued by the People’s Bank of China, and the designs of the notes reflect the concerns of the Communist Party of China. Renminbi – the People’s Money The money of the Mao era was the renminbi. This is still the name of the PRC's currency today - the ‘people’s money’, issued by the People’s Bank of China (renmin yinhang 人民银 行). The ‘people’ (renmin 人民) refers to all the people of China. There are 55 different ethnic groups: the Han (Hanzu 汉族) being the majority, and the 54 others known as ethnic minorities (shaoshu minzu 少数民族). While the term renminbi (人民币) deliberately establishes a contrast with the currency of the preceding Nationalist regime of Chiang Kai-shek, the term yuan (元) for the largest unit of the renminbi (which is divided into yuan, jiao 角, and fen 分) was retained from earlier currencies. Colloquially, the yuan is also known as kuai (块), literally ‘lump’ (of silver), which establishes a continuity with the silver-based currencies which China used formally until 1935 and informally until 1949. -

Political Trends in Russia

russian analytical russian analytical digest 60/09 digest analysis Fascist Tendencies in Russia’s Political Establishment: The Rise of the International Eurasian Movement By Andreas Umland, Eichstaett, Bavaria Abstract Aleksandr Dugin, a prominent advocate of fascist and anti-Western views, has risen from a fringe ideologue to deeply penetrate into Russian governmental offices, mass media, civil society and academia in ways that many in the West do not realize or understand. Prominent members of Russian society are affiliated with his International Eurasian Movement. Among Dugin’s most important collaborators are electronic and print media commentator Mikhail Leont’ev and the legendary TV producer and PR specialist Ivan Demidov. If Dugin’s views become more widely accepted, a new Cold War will be the least that the West should expect from Russia during the coming years. The Rise of Aleksandr Dugin course that must be taken seriously. Dugin’s numerous In recent years, various forms of nationalism have be- links to the political and academic establishments of a come a part of everyday Russian political and social life. number of post-Soviet countries, as well as institutions Since the end of the 1990s, an increasingly aggressive in Turkey, remain understudied or misrepresented. In racist sub-culture has been infecting sections of Russia’s other cases, Dugin and his followers receive more se- youth, and become the topic of numerous analyses by rious attention, yet are still portrayed as anachronis- Russian and non-Russian observers. Several new radi- tic, backward-looking imperialists – merely a partic- cal right-wing organizations, like the Movement Against ularly radical form of contemporary Russian anti-glo- Illegal Emigration, known by its Russian acronym balism. -

Recital Homenatge a Montserrat Caballé

JULIOL - AGOST 2019 ©Pavel Antonov SONDRA RADVANOVSKY RECITAL HOMENATGE A MONTSERRAT CABALLÉ www.festivalperalada.com EL FESTIVAL ÉS POSSIBLE GRÀCIES A: ESGLÉSIA DEL SONDRA CARME Moltes gràcies per ajudar-nos a fer-ho possible! 17 D’AGOST Presentat per: Patrocinador Principal: RADVANOVSKY RECITAL HOMENATGE A MONTSERRAT CABALLÉ Amb el copatrocini de: Sondra RADVANOVSKY, soprano Anthony MANOLI, piano Amb la col·laboració de: ® I II Giulio CACCINI (1551-1618) Gioacchino ROSSINI (1792-1868) Amarilli, mia bella La regata veneziana: 1) Anzoleta avanti la regata Amb el suport de: pantone 378 c Alessandro SCARLATTI (1660-1725) 2) Anzoleta co passa la regata Sento nel core 3) Anzoleta dopo la regata CCI FRANCE ESPAGNE CÁMARA DE COMERCIO FRANCESA Christoph Willibald GLUCK (1714-1787) Giacomo PUCCINI (1858-1924) desde 1883 O del mio dolce ardor Sole e amore Mitjans de comunicació oficials: Mitjans de comunicació col·laboradors: E l’uccellino Francesco DURANTE (1684-1755) Danza, danza, fanciulla gentile “Sola, perduta, abbandonata”, de Manon Lescaut Vincenzo BELLINI (1801-1835) Productes oficials: Per pieta, bell’idol mio Giuseppe VERDI La Ricordanza “Una macchia, è qui tuttora!”, Ma rendi pur contento de Macbeth Giuseppe VERDI (1813-1901) Festival Castell Peralada és membre de: El Festival dóna suport a: “Non so le tetre immagini”, d’Il Corsaro Agraïments: Gaetano Donizetti (1797-1848) “L’amor suo mi fe’ beata”, de Roberto Devereux ETERNA MONTSERRAT CABALLÉ arlar de Peralada és parlar de Montserrat Caballé. El fidel públic del Festival sap perfectament del què parlem, amb moltes nits de records inesborrables, com posa de manifest l’exposició PCaballé per sempre que es pot veure aquest estiu als jardins del Castell. -

Can the Soviet System Accommodate the “Democratic Movement”?

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-1974 Systemic Adaptation: Can the Soviet System Accommodate the “Democratic Movement”? Phillip A. Petersen Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Petersen, Phillip A., "Systemic Adaptation: Can the Soviet System Accommodate the “Democratic Movement”?" (1974). Master's Theses. 2588. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/2588 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SYSTEMIC ADAPTATION: CAN THE SOVIET SYSTEM ACCOMMODATE THE "DEMOCRATIC MOVEMENT"? by Phillip A. Petersen A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the Degree of Master of Arts Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan August 1974 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to begin by thanking Dr. Craig N. Andrews of Wayne State University for introducing me to the phenomenon of dissent in the Soviet Union. As for the project itself, Dr. John Gorgone of Western Michigan University not only suggested the approach to the phenomenon, but also had a fundamental role in shaping the perspective from which observations were made. The success of the research phase of the project is due, in great part, to the encouragement and assistance of Lt. Col. Carlton Willis of the Army Security Agency Training Center and School. -

University of Groningen Between Personal Experience and Detached

University of Groningen Between personal experience and detached information Harbers, Frank IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2014 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Harbers, F. (2014). Between personal experience and detached information: The development of reporting and the reportage in Great Britain, the Netherlands and France, 1880-2005. [S.l.]: [S.n.]. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 12-11-2019 Paranymphs Dominique van der Wal Marten Harbers Voor mijn vader en mijn moeder Graphic design Peter Boersma - www.hehallo.nl Printed by Wöhrmann Print Service Between Personal Experience and Detached Information The development of reporting and the reportage in Great Britain, the Netherlands and France, 1880-2005 Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Rijksuniversiteit Groningen op gezag van de rector magnificus prof. -

US-Soviet Public Diplomacy (04/01/1985-04/16/1985) Box: RAC Box 11

Ronald Reagan Presidential Library Digital Library Collections This is a PDF of a folder from our textual collections. Collection: Raymond, Walter: Files Folder Title: US-Soviet Public Diplomacy (04/01/1985-04/16/1985) Box: RAC Box 11 To see more digitized collections visit: https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/archives/digitized-textual-material To see all Ronald Reagan Presidential Library inventories visit: https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/archives/white-house-inventories Contact a reference archivist at: [email protected] Citation Guidelines: https://reaganlibrary.gov/archives/research- support/citation-guide National Archives Catalogue: https://catalog.archives.gov/ WITHDRAWAL SHEET Ronald Reagan Library Collection Name RAYMOND, WALTER: FILES Withdrawer KML 2/28/2012 File Folder U.S.-SOVIET PUBLIC DIPLOMACY (04/01/1985- FOIA 04/16/1985) Ml0-326/2 Box Number 11 PARRY 63 ID Doc Type Document Description No of Doc Date Restrictions Pages 132389 MEMO JOHN LENCZOWSKI TO ROBERT 2 4/1 6/1 985 Bl MCFARLANE RE WI CK PROPOSAL R 6/8/2018 M326/2 132390 MEMO ROBERT MCFARLANE TO THE PRESIDENT ND Bl RE WI CK PROPOSAL 132391 MEMO FOR NICHOLAS PLATT RE WICK PROPOSAL ND Bl 132392 MEMO TO CHARLES WICK RE PROPOSAL ND Bl Freedom of Information Act - (5 U.S.C. 552(b)] B-1 National security classified information [(b)(1) of the FOIA] B-2 Release would disclose internal personnel rules and practices of an agency [(b)(2) of the FOIA] B-3 Release would violate a Federal statute [(b)(3) of the FOIA] B-4 Release would disclose trade secrets or confidential or financial information [(b)(4) of the FOIA] B-6 Release would constitute a clearly unwarranted Invasion of personal privacy [(b)(6) of the FOIA] B-7 Release would disclose Information compiled for law enforcement purposes [(b)(7) of the FOIA] B-8 Release would disclose information concerning the regulation of financial institutions [(b)(8) of the FOIA] B-9 Release would disclose geological or geophysical Information concerning wells [(b)(9) of the FOIA] C. -

Bul NKVD AJ.Indd

The NKVD/KGB Activities and its Cooperation with other Secret Services in Central and Eastern Europe 1945 – 1989 Anthology of the international conference Bratislava 14. – 16. 11. 2007 Edited by Alexandra Grúňová Nation´s Memory Institute BRATISLAVA 2008 Anthology was published with kind support of The International Visegrad Fund. Visegrad Fund NKVD/KGB Activities and its Cooperation with other Secret Services in Cen- tral and Eastern Europe 1945 – 1989 14 – 16 November, 2007, Bratislava, Slovakia Anthology of the international conference Edited by Alexandra Grúňová Published by Nation´s Memory Institute Nám. SNP 28 810 00 Bratislava Slovakia www.upn.gov.sk 1st edition English language correction Anitra N. Van Prooyen Slovak/Czech language correction Alexandra Grúňová, Katarína Szabová Translation Jana Krajňáková et al. Cover design Peter Rendek Lay-out, typeseting, printing by Vydavateľstvo Michala Vaška © Nation´s Memory Institute 2008 ISBN 978-80-89335-01-5 Nation´s Memory Institute 5 Contents DECLARATION on a conference NKVD/KGB Activities and its Cooperation with other Secret Services in Central and Eastern Europe 1945 – 1989 ..................................................................9 Conference opening František Mikloško ......................................................................................13 Jiří Liška ....................................................................................................... 15 Ivan A. Petranský ........................................................................................ -

Putin's New Russia

PUTIN’S NEW RUSSIA Edited by Jon Hellevig and Alexandre Latsa With an Introduction by Peter Lavelle Contributors: Patrick Armstrong, Mark Chapman, Aleksandr Grishin, Jon Hellevig, Anatoly Karlin, Eric Kraus, Alexandre Latsa, Nils van der Vegte, Craig James Willy Publisher: Kontinent USA September, 2012 First edition published 2012 First edition published 2012 Copyright to Jon Hellevig and Alexander Latsa Publisher: Kontinent USA 1800 Connecticut Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20009 [email protected] www.us-russia.org/kontinent Cover by Alexandra Mozilova on motive of painting by Ilya Komov Printed at Printing house "Citius" ISBN 978-0-9883137-0-5 This is a book authored by independent minded Western observers who have real experience of how Russia has developed after the failed perestroika since Putin first became president in 2000. Common sense warning: The book you are about to read is dangerous. If you are from the English language media sphere, virtually everything you may think you know about contemporary Rus- sia; its political system, leaders, economy, population, so-called opposition, foreign policy and much more is either seriously flawed or just plain wrong. This has not happened by accident. This book explains why. This book is also about gross double standards, hypocrisy, and venal stupidity with western media playing the role of willing accomplice. After reading this interesting tome, you might reconsider everything you “learn” from mainstream media about Russia and the world. Contents PETER LAVELLE ............................................................................................1 -

Homosexuality in the USSR (1956–82)

Homosexuality in the USSR (1956–82) Rustam Alexander Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2018 School of Historical and Philosophical Studies Faculty of Arts The University of Melbourne Abstract The history of Soviet homosexuality is largely unexplored territory. This has led some of the few scholars who have examined this topic to claim that, in the period from Stalin through to the Gorbachev era, the issue of homosexuality was surrounded by silence. Such is the received view and in this thesis, I set out to challenge it. My investigation of a range of archival sources, including reports from the Soviet Interior Ministry (MVD), as well as juridical, medical and sex education literature, demonstrates that although homosexuality was not widely discussed in the broader public sphere, there was still lively discussion of it in these specialist and in some cases classified texts, from 1956 onwards. The participants of these discussions sought to define homosexuality, explain it, and establish their own methods of eradicating it. In important ways, this handling of the issue of homosexuality was specific to the Soviet context. This thesis sets out to broaden our understanding of the history of official discourses on homosexuality in the late Soviet period. This history is also examined in the context of and in comparison to developments on this front in the West, on the one hand, and Eastern Europe, on the other. The thesis draws on the observation made by Dan Healey, the pioneering scholar of Russian and Soviet sexuality, that in the Soviet Union after Stalin’s death a combination of science and police methods was used to strengthen heterosexual norms in the Soviet society. -

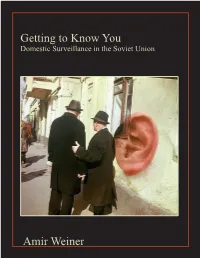

Getting to Know You. the Soviet Surveillance System, 1939-1957

Getting to Know You Domestic Surveillance in the Soviet Union Amir Weiner Forum: The Soviet Order at Home and Abroad, 1939–61 Getting to Know You The Soviet Surveillance System, 1939–57 AMIR WEINER AND AIGI RAHI-TAMM “Violence is the midwife of history,” observed Marx and Engels. One could add that for their Bolshevik pupils, surveillance was the midwife’s guiding hand. Never averse to violence, the Bolsheviks were brutes driven by an idea, and a grandiose one at that. Matched by an entrenched conspiratorial political culture, a Manichean worldview, and a pervasive sense of isolation and siege mentality from within and from without, the drive to mold a new kind of society and individuals through the institutional triad of a nonmarket economy, single-party dictatorship, and mass state terror required a vast information-gathering apparatus. Serving the two fundamental tasks of rooting out and integrating real and imagined enemies of the regime, and molding the population into a new socialist society, Soviet surveillance assumed from the outset a distinctly pervasive, interventionist, and active mode that was translated into myriad institutions, policies, and initiatives. Students of Soviet information systems have focused on two main features—denunciations and public mood reports—and for good reason. Soviet law criminalized the failure to report “treason and counterrevolutionary crimes,” and denunciation was celebrated as the ultimate civic act.1 Whether a “weapon of the weak” used by the otherwise silenced population, a tool by the regime