Service and Civic Engagement Self-Study Task Force Final Report, June 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

May Issue, 2003

THE TORY SALUTES THE CLASS OF 2003 April - May 2003 PRINCETON TORY On the legacy of Dean Fred Hargadon, and the administration trying to rewrite it... - BRAD SIMMONS ’03 PLUS: JENN CARTER ’03 on the Emptiness of “The Princeton Experience” PETE HEGSETH ’03 on Victory in Iraq DANIEL MARK ’03 on Abortion, Slavery, and the Democratic Party And much more! Notes from the Publisher HE RINCETON T P Amoebas on the Slide TORY Engineering is everywhere you look at Princeton. No, I’m not April - May 2003 just talking about my department, ORFE, or the E-Quad. I’m referring to Volume XX - Number 3 social engineering. Publisher Editor-in-Chief The racial “diversity” of the entering class is engineered to some John Andrews ’05 Evan Baehr ’05 arbitrarily-designated optimal ratio. The life of the athlete is engineered to some quota of practice and, well, anything-but-practice. The bounds of Managing Editors acceptable campus speech and religious practice are engineered to a non- Brad Heller ’05 Duncan Sahner ’06 offensive beige by a gauntlet of advisers, peer educators, and deans. Web Manager Financial Manager What’s scary about this social engineering is not its current level Eric Czervionke ’05 Ira Leeds ’06 of control but the conclusion that this engineering is increasing, a conclu- sion made inevitable by recent events. Some examples are ones with Graphics Editor which you may be familiar: Tilghman’s athletics moratorium and amicus Deb Brundage ’03 brief, and the Bush-bashing fest sponsored by the Wilson School. I hope Pete Hegseth ’03, Publisher Emeritus you’ll read this issue and find more examples, from Murray-Dodge to the Brad Simmons ’03, Editor-in-Chief Emeritus Office of Admissions to a subjective and multiculturalist curriculum. -

The Politics of Saudi Arabia's New University

T The Princeton ory December 2008 Tilghman’s Gamble Arabia’sThe Politics New University of Saudi December 2008 ALSO: AN EXC L U S IV E INT E RVI E W WITH PR O F Sea N WI le NTZ O N TH E Ele CTI O N AFT E RM A TH The Princeton Letter from the Publisher Tory A Party Blessed with Defeat December 2008 The election of Barack Obama is at once the Volume XXV - Issue V worst thing that could have happened to the country and the best thing that could have happened to the Table of Contents Republican Party. In the aftermath of November 4, Publisher conservatives have tended to focus too much on the Joel Alicea ‘10 former and not enough on the latter. True, the elec- tion bodes ill for the nation for the next four years. Editor-in-Chief Managing Editors At a time when the country is in the midst of what Leon Furchtgott ‘09 Brandon McGinley ‘10 is being described as the worst economic down- Andrew Saraf ‘11 turn since the Great Depression, the man we have Copy Editors selected to lead us through this crisis was only four Robert Day ‘10 Production Manager years ago an undistinguished state senator who has Katie Fletcher ‘10 Robert Day ‘10 since become an unaccomplished member of Con- Shivani Radhakrishnan ‘11 gress. As we wage war against a ruthless and determined enemy in two theatres Production Assisstant and face the most consequential foreign policy decisions since the end of the Cold War, the Commander-in-Chief is to be a man whose statements on these issues are Financial Manager Alfred Miller ‘11 dangerously naïve and foolhardy, a man no person could reasonably claim has the Brendan Lyons ‘09 experience to handle such challenges. -

Mccoshed: a Special Investigation Reveals Incompetence and Ethical Lapses at Princeton’S Health Center

THE March 2008 PRINCETON TORY McCoshed: A special investigation reveals incompetence and ethical lapses at Princeton’s health center Also Inside: The untold story of the Nava response Princeton’s Preacher Sex Jeopardy! & Whit Stillman From the Publisher THE THE PRINCETON A special investigation in this issue of the Tory reveals that after a 116-year history of serv- TORY ing the campus community, McCosh Clinic March 2007 has recently been plagued by ethics lapses and PRINCETON TORY Volume XXIV - Issue IV March 2008 www.princeton.edu/~tory violations of state law. Since 2003, McCosh has Publisher Matthew J. Schmitz ’08 broken the law by failing to send in important data used to protect students from outbreaks of Editor in Chief Senior Managing Sherif Girgis ’08 Editor STDs. During the same time, McCosh’s direc- Jordan Reimer ’08 tor, Daniel Silverman, established a relationship with a consulting firm that violated university Production Manager Financial Manager Rick Morgan ’09 Matt Martin ’08 ethics rules and resulted in a lucrative job for Silverman. IN TH I S ISSUE : Managing Editors Production Team Emely Peña’09 Brendan Lyons ’09 Despite the fact that Silverman has left the Leon Furchtgott ’09 Julius Dimas ’09 University, Princeton has decided to continue MCCOSHED : COVER STORY ON PAGE 14 to pay for his advice as an outside consultant. Publisher Emeritus Webmaster Juliann Vikse ’08 Johnny Love ’09 His job? Telling Princeton how to improve its health services. Students, parents TORY EXCLUSIVE ON NEW JERSEY ’S INVES T IGA T ION OF MCCOSH and alumni should demand that Silverman and his firm be barred from receiving any more of Princeton’s money. -

Feb-March 2002

THE PRINCETON TORY February-March 2002 www.princetontory.com Coming Out of the Closet Notes from the Publisher THE PRINCETON Princeton University is, in its most profound sense, an institution dedicated to the education and cultivation of tomorrow’s leaders. And in TORY pursuit of a well-rounded liberal arts February-March 2002 education, Princetonians are constantly Volume XIX - Number 1 involved in the timeless exchange of ideas. From the moment we arrive on campus, a Publisher Editor in Chief wide range of ideologies are thrown in our Pete Hegseth ’03 Brad Simmons ’03 direction. From the Marxists to the atheist Managing Editors Religion Professors to the Secular Humanists, Jennifer Carter ’03 Nitesh Paryani ’05 Princeton’s got ’em all. However, underneath all the liberal noise, there is a Layout Editor Content Editor traditional core to the Princeton experience. It is that core which Amy Burghardt ’05 Nat Hoopes ’03 The Princeton Tory seeks to rediscover. The Tory original Statement of Principles, written in 1984, sums up our mission well: Web Manager Financial Manager “Our objective is to legitimate conservatism as a philosophy and as Brian Beck ’05 Ryan Feeney ’03 an approach for those reformers who seek to ameliorate our social Staff Writers and political problems. We present our views as a challenge to those Nathaniel Norman ’03 Matt O’Brien ’03 who would build their new world by destroying many of those very Carlos Mrosovsky ’04 Pete Sutherland ’04 qualities which we value in our civilization.” Arvin Bahl ’05 John Brunger ’05 As conservatives it is our duty to present the other side of Jonathan Bydlak ’05 Dan Larach ’05 the story—the right side. -

Art & Archaeology Newsletter

PrincetonUniversity DEPARTMENT OF Art Archaeology & Newsletter Dear Friends and Colleagues: SPRING 7 We have entered a period of transfor- Yet the most important change concerns the Inside faculty. In the next five years no fewer than eight mation. Our self-study in 2006–07 distinguished senior colleagues, in fields that extend from ancient and Byzantine to Italian Renaissance resulted in several changes in the cur- FACULTY NEWS and American, will retire or depart. This year alone riculum; for example, Art 101 is now we bid farewell to two important figures, John two courses, and the junior seminar Wilmerding and Carol Armstrong. Hence rebuild- 8 ing and extending the faculty is much on our VISUAL ARTS FACULTY for majors is now a regular course in minds. Indeed, our season of new hires has already methodology. begun: as I write, we are concluding two searches, a senior position in Japanese art, to replace our Last fall, a distinguished committee of external LECTURES, SYMPOSIUMS, esteemed colleague Yoshiaki Shimizu, and a junior reviewers supported these initiatives and suggested COLLOQUIUMS position in Northern European art of circa 1400– more—including a more integrative proseminar 1800. Next year we will undertake at least two and a more rigorous requirement in a minor field more searches: a broadly defined senior position in 4 for our graduate students—which we have ancient art and/or archaeology and a junior hire in GRADUATE STUDENT NEWS adopted. African art, a field we have long wished to represent The review also urged us to highlight our at Princeton. As we search in these areas—and in “cross-cutting” strengths in architectural history 8 others in the years and archaeology, UNDERGRADUATE NEWS ahead—we will col- and we have since laborate with other moved to collabo- departments and 3 rate more effectively programs, both EXCAVATIONS with the School of new and old, such Architecture and as classics and the have extended our 5 Center for African Program 3 from INDEX OF CHRISTIAN ART American Studies. -

Freshman Issue, 2005

THE PRINCETON From the Publisher TORY September 2005 Volume XXII - Issue IV Dear freshmen, Publisher Editor Emeritus Ira Leeds ’06 Duncan Sahner ’06 Twenty-one years ago this month, a group of Princeton students led by Yoram Hazony ’86, Senior Managing Editors Daniel Polisar ’87, and Peter Heinecke ’87 decided Paul Thompson ’06 Jurgen Reinhoudt ’06 that the rampant liberalism overtaking Princeton’s Managing Editors campus had to be checked. These enterprising Christian Sahner ’07 Ward Benson ’07 individuals founded The Princeton Tory as a voice of moderate and conservative political thought to Copy Editors act as a counter to the liberal bias that had saturated Powell Fraser ’06 Stephen Lambe ’06 the administration and many professors alike. Financial Manager Operations Manager The bad news is that today liberalism is still well J. Ruben Pope ’07 Robert W. Wong ’06 entrenched in this educational institution. However, across the nation, liberalism is finding itself caught Production Team in a much harder fight to keep its predominance on college campuses. The Mike Kratsios ’08 growing campus conservatism movement is finally taking ground back from Matt Martin ’08 its Princeton’s liberal overseers. The Tory was one of the first student groups to answer the call to arms, and we hold in high esteem those who came before Staff Writers us. Even with the gains made by our predecessors we still have a lot of Julie Toran ’05 Clarke Smith ’07 work ahead of us. As one of the most-read publications on campus and the Mike Fragoso ’06 Marissa Troiano ’06 Marissa Troiano ’06 Jordan Reimer ’08 only one with a true conservative lean, we have an obligation to further the Stuart Lange ’07 Will Scharff ’08 discussion and debate of conservative ideals and their relation to the politics of Matt MacDonald ’07 Juliann Vikse ’08 the moment. -

OUR LATEST Laureate a Ngus Deaton Wins the Nobel Prize in Economics

REMEMBERING 75 YEARS LIMITATIONS ON C.K. WILLIAMS WITH WPRB CAMPUS SPEECH? PRINCETON ALUMNI WEEKLY OUR LATEST LAUREATE A ngus Deaton wins the Nobel Prize in economics NOVEMBER 11, 2015 PAW.PRINCETON.EDU 00paw1111_Cover2.indd 1 10/28/15 10:38 AM S:7” Invest In What Lasts How do you pass down what you’ve spent your life building up? A Morgan Stanley Financial Advisor can help you create a legacy plan based on the values you live by. So future generations can benefit from not just your money, but also your example. Let’s have that conversation. morganstanley.com/legacy S:9.25” © 2015 Morgan Stanley Smith Barney LLC. Member SIPC. CRC 1134840 04/15 November 11, 2015 Volume 116, Number 4 An editorially independent magazine by alumni for alumni since 1900 P RESIDENT’S PAGE 2 INBOX 5 FROM THE EDITOR 6 ON THE CAMPUS 13 Angus Deaton wins Nobel Public-safety officers gain access to guns African American studies now a department Endowment results Remembering C.K. Williams STUDENT DISPATCH: Anscombe Society SPORTS: Women’s basketball Road to Rio LIFE OF THE MIND 25 Stacey Sinclair on implicit bias Marina Rustow on the Cairo Geniza Harry G. Frankfurt on inequality PRINCETONIANS 39 Josh Morris ’99, rock climber “We Flourish” alumni conference Historian Gordon Chang ’70 Ken Katkin ’87, a WPRB DJ, in CLASS NOTES 43 1984, page 28 MEMORIALS 62 The Voice of Princeton 28 Can We Say That? 32 WPRB, our much-loved campus radio Across the country, there are calls for CLASSIFIEDS 70 station, is celebrating its 75th anniversary. -

October 2004

May 2004 May 2004 Including: Kerry and Catholicism Christianity in the Classroom Same-Sex Marriage And more... THE PRINCETON From the Publisher TORY Dear fellow Princetonians, October 2004 Volume XXI - Issue IV In watching the presidential Publisher Editor-in-Chief and vice-presidential debates over the Ira Leeds ’06 Duncan Sahner ’06 last few weeks, I have been pleasantly surprised to see an increase in the actual Managing Editors Brad Heller ’05 debating of ideas in this election versus Powell Fraser ’06 Jurgen Reinhoudt ’06 presidential elections-past. Now before I overstate my position, please do not Financial Manager think that I have found ideological Paul Thompson ’06 substance to the debates themselves. Production Team No, no, that would be too much of a Stephen Lambe’06 Ruben Pope ’07 blessing. Nevertheless, on Princeton’s campus and across the nation it is the Publisher Emeritus Editor Emeritus first time in a long time where political John Andrews ’05 Evan Baehr ’05 debate has risen above one banal issue such as tax policy or social security reform. With both major political parties Staff Writers fielding relatively extreme presidential candidates, this election has actually turned into an ideological battleground that I would argue has produced a Julie Toran ’05 Eleanor Mulhern ’07 healthy political debate. Marissa Troiano ’06 Christian Sahner ’07 In an era where political apathy has reached new heights and voter Stuart Lange ’07 Clarke Smith ’07 participation has sunk to new lows, perhaps what the country really needs is Ward Benson ’07 Marissa Troiano ’06 a messy, antagonizing, ugly election. -

Assessing the Morality of the Egg Donation Business in The

Egg “Donation?”—Assessing the Morality of the Egg Donation Business in the United States through the Lens of Virtue Ethics. By: Gina Milano Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment for Honors in Science and Society, A.B. Brown University April 15, 2016 Thesis Advisor: Timothy P. Flanigan, M.D. Second Reader: Kenneth R. Miller, Ph.D. Table of Contents Abstract………………………………………………………………………………pg. 3 Introduction……………………………………………………..…………………pg. 4-5 Chapter I: Egg Donation…………………….………………………….……….pg. 6-16 Chapter II: The Case for Virtue Ethics………………………………..…….....pg. 17-23 Chapter III: Virtue Ethics and Egg Donation………………………………....pg. 24-34 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………….pg. 35-37 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………….pg. 38-42 2 Abstract In this paper I aim to address whether the current egg donation business in the United States is moral. First, I investigate the egg donation business in the United States. My research focuses on: what the egg donation business is, how the business is successful, who is involved, and why it is so popular. Ethical dilemmas associated with egg donation involve monetary compensations for human eggs, unknown serious health risks for donors, and consequences of the technology failing. Next, I evaluated different ethical theories to apply to this bioethical issue. I found virtue ethics as the most convincing and I present a case for it in Chapter 2. Finally, in Chapter 3, I use virtue ethics as a lens to assess the morality of the egg donation business. Here, I argue that if virtue ethics is true, then, the egg donation process in the United States is morally wrong. I conclude my paper with possible solutions to help make egg donation more in line with living a virtuous life. -

Freshman Issue, 2003

Freshman Issue September 2003 PRINCETON TORY Special Report: Professors and Politics plus The Issues 2003-04 and THE RANT THE PRINCETON Notes from the Publisher Microwave-Safe Plato TORY Mongers of the intellectual crisis, eat your hearts out: September 2003 This summer in Washington, where I worked at a conservative Volume XX - Issue IV think tank, I left the barbershop where I had trimmed up before the Tory Publisher Editor-in-Chief went on camera. (Tory editors, past and present, will appear alongside John Andrews ’05 Evan Baehr ’05 William F. Buckley and Justice Antonin Scalia in a celebration of the fifti- Managing Editors eth anniversary of the Intercollegiate Studies Institute.) Brad Heller ’05 Duncan Sahner ’06 Newly shorn and sauntering back to the train, I paused in a small, musty, second-hand bookshop. While browsing I found, gathering dust Web Manager Financial Manager and a bit of mildew, a 1937 edition of the Harvard Classics, Dr. Charles Eric Czervionke ’05 Ira Leeds ’06 Eliot’s “Five-Foot Shelf of Books.” The fifty-two volume set was priced, Graphics Editor and seemed to have been for many years, at fifty dollars. What a bargain! Deb Brundage ’03 Happily, I paid the full price. I returned after the taping, wheeling a large suitcase to collect the set. Pete Hegseth ’03, Publisher Emeritus The Classics cleaned up quite handsomely, making a wonderful Brad Simmons ’03, Editor-in-Chief Emeritus addition to my library. Sometime in my second-hand book-buying past, I Staff Writers learned that a good way to kill mildew spores is to heat the book in a microwave, and then give it a good dusting. -

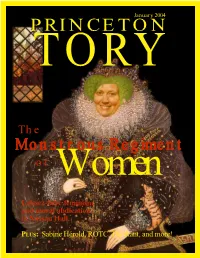

January Issue, 2004

January 2004 PRINCETON TORY The MonsMonstrtrousous RRegimentegiment of Women Laissez-faire feminism and moral abdication in Nassau Hall. PLUS: Sabine Hérold, ROTC, The Rant, and more! Notes from the Publisher THE PRINCETON Hail and Farewell TORY As this issue of the Tory is the last that I will publish, I’ve decided January 2004 to go out swinging. Prediction time. Volume XXI - Issue I I am not optimistic about the future of the University. We students are witnessing the erosion, unchecked and accelerating since the sixties, Publisher Editor-in-Chief of every institution that makes Princeton Princeton. Before our children’s John Andrews ’05 Evan Baehr ’05 time, the only distinctions remaining will be statues cowering in niches and epitaphs furtively chiseled in archways. This University will be just Managing Editors Brad Heller ’05 Duncan Sahner ’06 another Brown, or, God help us, Yale. The conservative student movement is strong, and I’ve found the student body’s response to the Tory Web Manager Financial Manager Eric Czervionke ’05 Ira Leeds ’06 heartening. However, there is no democratic recourse against a self- perpetuating liberal elite that simply brushes aside, and unfairly, I believe, Graphics Editor not just student publications like the Tory but an enormous body of well- Deb Brundage ’03 reasoned dissent from some of the brightest and most seasoned academics and commentators in the country. The only bright side I can see is that Staff Writers the future will provide ample material for Tory articles. I find enormous hope, however, in the state of the nation as a John Ference ’04 Ward Benson ’07 whole. -

To Reclaim a Legacy of Diversity: Analyzing the "Political Correctness" Debates in Higher Education

DOCUMENT AESUME ED 364 170 HE 026 973 AUTHOR Schultz, Debra L.; And Others TITLE To Reclaim a Legacy of Diversity: Analyzing the "Political Correctness" Debates in Higher Education. INSTITUTION National Council for Research on Women,, New York, NY. PUB DATE 93 NOTE 76p. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council for Research on Women, 530 Broadway at Spring Street, 10th Floor, New York, NY 10012 ($12). PUB TYPE Information Analyses (070) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS College Curriculum; Conservatism; Curriculpm Development; Ethnic Groups; Ethnic Studies; Financial Support; Higher Education; Liberalism; *Mass Media Role; Minority Groups; *Multicultural Education; Negative Attitudes; Political Influences; Politics of Education; Resistance (Psychology); *Social Action; ( Social Attitudes; Womens Studies IDENTIFIERS *Diversity (Groups); *Political Correctness ABSTRACT "Political correctness" has recently been appropriated by organizations and individual advocates seeking to attack and focus negative media att.ention on reforms in higher education. This report documents both the facts and media distortions that have shaped almost a decade of campus debate on affirmative action, multicultural and feminist curriculum reform, and programs to diversify college campuses. The report also highlights the conditions that have given rise to an unrivaled backlash in academia. Topics addressed include media coverage of political correctness, conservative activism in higher education, liberal responses to the backlash, funding patterns, and campus violence/campus climate issues. Appendices include a chronological list of media coverage that addressed political correctness issues between 1989 and 1993, a list of activist networks of student newspapers on campuses, statistics concerning people of color and women in higher education, the addresses and phone numbers of National Council for Research on Women Member Centers throughout the country, and a list of selected guides and resources concerning integrating women of color into the curriculum.