Building Polyhedra Models for Mathematical Art Projects and Teaching Geometry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Poster

Associating Finite Groups with Dessins d’Enfants Luis Baeza, Edwin Baeza, Conner Lawrence, and Chenkai Wang Abstract Platonic Solids Rotation Group Dn: Regular Convex Polygon Approach Each finite, connected planar graph has an automorphism group G;such Following Magot and Zvonkin, reduce to easier cases using “hypermaps” permutations can be extended to automorphisms of the Riemann sphere φ : P1(C) P1(C), then composing β = φ f where S 2(R) P1(C). In 1984, Alexander Grothendieck, inspired by a result of f : 1( ) ! 1( )isaBely˘ımapasafunctionofeither◦ zn or ' P C P C Gennadi˘ıBely˘ıfrom 1979, constructed a finite, connected planar graph 4 zn/(zn +1)! 2 such that Aut(f ) Z or Aut(f ) D ,respectively. ' n ' n ∆β via certain rational functions β(z)=p(z)/q(z)bylookingatthe inverse image of the interval from 0 to 1. The automorphisms of such a Hypermaps: Rotation Group Zn graph can be identified with the Galois group Aut(β)oftheassociated 1 1 rational function β : P (C) P (C). In this project, we investigate how Rigid Rotations of the Platonic Solids I Wheel/Pyramids (J1, J2) ! w 3 (w +8) restrictive Grothendieck’s concept of a Dessin d’Enfant is in generating all n 2 I φ(w)= 1 1 z +1 64 (w 1) automorphisms of planar graphs. We discuss the rigid rotations of the We have an action : PSL2(C) P (C) P (C). β(z)= : v = n + n, e =2 n, f =2 − n ◦ ⇥ 2 !n 2 4 zn · Platonic solids (the tetrahedron, cube, octahedron, icosahedron, and I Zn = r r =1 and Dn = r, s s = r =(sr) =1 are the rigid I Cupola (J3, J4, J5) dodecahedron), the Archimedean solids, the Catalan solids, and the rotations of the regular convex polygons,with 4w 4(w 2 20w +105)3 I φ(w)= − ⌦ ↵ ⌦ 1 ↵ Rotation Group A4: Tetrahedron 3 2 Johnson solids via explicit Bely˘ımaps. -

Volumes of Prisms and Cylinders 625

11-4 11-4 Volumes of Prisms and 11-4 Cylinders 1. Plan Objectives What You’ll Learn Check Skills You’ll Need GO for Help Lessons 1-9 and 10-1 1 To find the volume of a prism 2 To find the volume of • To find the volume of a Find the area of each figure. For answers that are not whole numbers, round to prism a cylinder the nearest tenth. • To find the volume of a 2 Examples cylinder 1. a square with side length 7 cm 49 cm 1 Finding Volume of a 2. a circle with diameter 15 in. 176.7 in.2 . And Why Rectangular Prism 3. a circle with radius 10 mm 314.2 mm2 2 Finding Volume of a To estimate the volume of a 4. a rectangle with length 3 ft and width 1 ft 3 ft2 Triangular Prism backpack, as in Example 4 2 3 Finding Volume of a Cylinder 5. a rectangle with base 14 in. and height 11 in. 154 in. 4 Finding Volume of a 6. a triangle with base 11 cm and height 5 cm 27.5 cm2 Composite Figure 7. an equilateral triangle that is 8 in. on each side 27.7 in.2 New Vocabulary • volume • composite space figure Math Background Integral calculus considers the area under a curve, which leads to computation of volumes of 1 Finding Volume of a Prism solids of revolution. Cavalieri’s Principle is a forerunner of ideas formalized by Newton and Leibniz in calculus. Hands-On Activity: Finding Volume Explore the volume of a prism with unit cubes. -

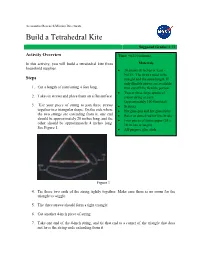

Build a Tetrahedral Kite

Aeronautics Research Mission Directorate Build a Tetrahedral Kite Suggested Grades: 8-12 Activity Overview Time: 90-120 minutes In this activity, you will build a tetrahedral kite from Materials household supplies. • 24 straws (8 inches or less) - NOTE: The straws need to be Steps straight and the same length. If only flexible straws are available, 1. Cut a length of yarn/string 4 feet long. then cut off the flexible portion. • Two or three large spools of 2. Take six straws and place them on a flat surface. cotton string or yarn (approximately 100 feet total) 3. Use your piece of string to join three straws • Scissors together in a triangular shape. On the side where • Hot glue gun and hot glue sticks the two strings are extending from it, one end • Ruler or dowel rod for kite bridle should be approximately 20 inches long, and the • Four pieces of tissue paper (24 x other should be approximately 4 inches long. 18 inches or larger) See Figure 1. • All-purpose glue stick Figure 1 4. Tie these two ends of the string tightly together. Make sure there is no room for the triangle to wiggle. 5. The three straws should form a tight triangle. 6. Cut another 4-inch piece of string. 7. Take one end of the 4-inch string, and tie that end to a corner of the triangle that does not have the string ends extending from it. Figure 2. 8. Add two more straws onto the longest piece of string. 9. Next, take the string that holds the two additional straws and tie it to the end of one of the 4-inch strings to make another tight triangle. -

THE GEOMETRY of PYRAMIDS One of the More Interesting Solid

THE GEOMETRY OF PYRAMIDS One of the more interesting solid structures which has fascinated individuals for thousands of years going all the way back to the ancient Egyptians is the pyramid. It is a structure in which one takes a closed curve in the x-y plane and connects straight lines between every point on this curve and a fixed point P above the centroid of the curve. Classical pyramids such as the structures at Giza have square bases and lateral sides close in form to equilateral triangles. When the closed curve becomes a circle one obtains a cone and this cone becomes a cylindrical rod when point P is moved to infinity. It is our purpose here to discuss the properties of all N sided pyramids including their volume and surface area using only elementary calculus and geometry. Our starting point will be the following sketch- The base represents a regular N sided polygon with side length ‘a’ . The angle between neighboring radial lines r (shown in red) connecting the polygon vertices with its centroid is θ=2π/N. From this it follows, by the law of cosines, that the length r=a/sqrt[2(1- cos(θ))] . The area of the iscosolis triangle of sides r-a-r is- a a 2 a 2 1 cos( ) A r 2 T 2 4 4 (1 cos( ) From this we have that the area of the N sided polygon and hence the pyramid base will be- 2 2 1 cos( ) Na A N base 2 4 1 cos( ) N 2 It readily follows from this result that a square base N=4 has area Abase=a and a hexagon 2 base N=6 yields Abase= 3sqrt(3)a /2. -

The Volumes of a Compact Hyperbolic Antiprism

The volumes of a compact hyperbolic antiprism Vuong Huu Bao joint work with Nikolay Abrosimov Novosibirsk State University G2R2 August 6-18, Novosibirsk, 2018 Vuong Huu Bao (NSU) The volumes of a compact hyperbolic antiprism Aug. 6-18,2018 1/14 Introduction Calculating volumes of polyhedra is a classical problem, that has been well known since Euclid and remains relevant nowadays. This is partly due to the fact that the volume of a fundamental polyhedron is one of the main geometrical invariants for a 3-dimensional manifold. Every 3-manifold can be presented by a fundamental polyhedron. That means we can pair-wise identify the faces of some polyhedron to obtain a 3-manifold. Thus the volume of 3-manifold is the volume of prescribed fundamental polyhedron. Theorem (Thurston, Jørgensen) The volumes of hyperbolic 3-dimensional hyperbolic manifolds form a closed non-discrete set on the real line. This set is well ordered. There are only finitely many manifolds with a given volume. Vuong Huu Bao (NSU) The volumes of a compact hyperbolic antiprism Aug. 6-18,2018 2/14 Introduction 1835, Lobachevsky and 1982, Milnor computed the volume of an ideal hyperbolic tetrahedron in terms of Lobachevsky function. 1993, Vinberg computed the volume of hyperbolic tetrahedron with at least one vertex at infinity. 1907, Gaetano Sforza; 1999, Yano, Cho ; 2005 Murakami; 2005 Derevnin, Mednykh gave different formulae for general hyperbolic tetrahedron. 2009, N. Abrosimov, M. Godoy and A. Mednykh found the volumes of spherical octahedron with mmm or 2 m-symmetry. | 2013, N. Abrosimov and G. Baigonakova, found the volume of hyperbolic octahedron with mmm-symmetry. -

E8 Physics and Quasicrystals Icosidodecahedron and Rhombic Triacontahedron Vixra 1301.0150 Frank Dodd (Tony) Smith Jr

E8 Physics and Quasicrystals Icosidodecahedron and Rhombic Triacontahedron vixra 1301.0150 Frank Dodd (Tony) Smith Jr. - 2013 The E8 Physics Model (viXra 1108.0027) is based on the Lie Algebra E8. 240 E8 vertices = 112 D8 vertices + 128 D8 half-spinors where D8 is the bivector Lie Algebra of the Real Clifford Algebra Cl(16) = Cl(8)xCl(8). 112 D8 vertices = (24 D4 + 24 D4) = 48 vertices from the D4xD4 subalgebra of D8 plus 64 = 8x8 vertices from the coset space D8 / D4xD4. 128 D8 half-spinor vertices = 64 ++half-half-spinors + 64 --half-half-spinors. An 8-dim Octonionic Spacetime comes from the Cl(8) factors of Cl(16) and a 4+4 = 8-dim Kaluza-Klein M4 x CP2 Spacetime emerges due to the freezing out of a preferred Quaternionic Subspace. Interpreting World-Lines as Strings leads to 26-dim Bosonic String Theory in which 10 dimensions reduce to 4-dim CP2 and a 6-dim Conformal Spacetime from which 4-dim M4 Physical Spacetime emerges. Although the high-dimensional E8 structures are fundamental to the E8 Physics Model it may be useful to see the structures from the point of view of the familiar 3-dim Space where we live. To do that, start by looking the the E8 Root Vector lattice. Algebraically, an E8 lattice corresponds to an Octonion Integral Domain. There are 7 Independent E8 Lattice Octonion Integral Domains corresponding to the 7 Octonion Imaginaries, as described by H. S. M. Coxeter in "Integral Cayley Numbers" (Duke Math. J. 13 (1946) 561-578 and in "Regular and Semi-Regular Polytopes III" (Math. -

Archimedean Solids

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln MAT Exam Expository Papers Math in the Middle Institute Partnership 7-2008 Archimedean Solids Anna Anderson University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/mathmidexppap Part of the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Anderson, Anna, "Archimedean Solids" (2008). MAT Exam Expository Papers. 4. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/mathmidexppap/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Math in the Middle Institute Partnership at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in MAT Exam Expository Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Archimedean Solids Anna Anderson In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts in Teaching with a Specialization in the Teaching of Middle Level Mathematics in the Department of Mathematics. Jim Lewis, Advisor July 2008 2 Archimedean Solids A polygon is a simple, closed, planar figure with sides formed by joining line segments, where each line segment intersects exactly two others. If all of the sides have the same length and all of the angles are congruent, the polygon is called regular. The sum of the angles of a regular polygon with n sides, where n is 3 or more, is 180° x (n – 2) degrees. If a regular polygon were connected with other regular polygons in three dimensional space, a polyhedron could be created. In geometry, a polyhedron is a three- dimensional solid which consists of a collection of polygons joined at their edges. The word polyhedron is derived from the Greek word poly (many) and the Indo-European term hedron (seat). -

Platonic and Archimedean Geometries in Multicomponent Elastic Membranes

Platonic and Archimedean geometries in multicomponent elastic membranes Graziano Vernizzia,1, Rastko Sknepneka, and Monica Olvera de la Cruza,b,c,2 aDepartment of Materials Science and Engineering, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60208; bDepartment of Chemical and Biological Engineering, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60208; and cDepartment of Chemistry, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60208 Edited by L. Mahadevan, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, and accepted by the Editorial Board February 8, 2011 (received for review August 30, 2010) Large crystalline molecular shells, such as some viruses and fuller- possible to construct a lattice on the surface of a sphere such enes, buckle spontaneously into icosahedra. Meanwhile multi- that each site has only six neighbors. Consequently, any such crys- component microscopic shells buckle into various polyhedra, as talline lattice will contain defects. If one allows for fivefold observed in many organelles. Although elastic theory explains defects only then, according to the Euler theorem, the minimum one-component icosahedral faceting, the possibility of buckling number of defects is 12 fivefold disclinations. In the absence of into other polyhedra has not been explored. We show here that further defects (21), these 12 disclinations are positioned on the irregular and regular polyhedra, including some Archimedean and vertices of an inscribed icosahedron (22). Because of the presence Platonic polyhedra, arise spontaneously in elastic shells formed of disclinations, the ground state of the shell has a finite strain by more than one component. By formulating a generalized elastic that grows with the shell size. When γ > γà (γà ∼ 154) any flat model for inhomogeneous shells, we demonstrate that coas- fivefold disclination buckles into a conical shape (19). -

Systematics of Atomic Orbital Hybridization of Coordination Polyhedra: Role of F Orbitals

molecules Article Systematics of Atomic Orbital Hybridization of Coordination Polyhedra: Role of f Orbitals R. Bruce King Department of Chemistry, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA; [email protected] Academic Editor: Vito Lippolis Received: 4 June 2020; Accepted: 29 June 2020; Published: 8 July 2020 Abstract: The combination of atomic orbitals to form hybrid orbitals of special symmetries can be related to the individual orbital polynomials. Using this approach, 8-orbital cubic hybridization can be shown to be sp3d3f requiring an f orbital, and 12-orbital hexagonal prismatic hybridization can be shown to be sp3d5f2g requiring a g orbital. The twists to convert a cube to a square antiprism and a hexagonal prism to a hexagonal antiprism eliminate the need for the highest nodality orbitals in the resulting hybrids. A trigonal twist of an Oh octahedron into a D3h trigonal prism can involve a gradual change of the pair of d orbitals in the corresponding sp3d2 hybrids. A similar trigonal twist of an Oh cuboctahedron into a D3h anticuboctahedron can likewise involve a gradual change in the three f orbitals in the corresponding sp3d5f3 hybrids. Keywords: coordination polyhedra; hybridization; atomic orbitals; f-block elements 1. Introduction In a series of papers in the 1990s, the author focused on the most favorable coordination polyhedra for sp3dn hybrids, such as those found in transition metal complexes. Such studies included an investigation of distortions from ideal symmetries in relatively symmetrical systems with molecular orbital degeneracies [1] In the ensuing quarter century, interest in actinide chemistry has generated an increasing interest in the involvement of f orbitals in coordination chemistry [2–7]. -

Math 366 Lecture Notes Section 11.4 – Geometry in Three Dimensions

Section 11-4 Math 366 Lecture Notes Section 11.4 – Geometry in Three Dimensions Simple Closed Surfaces A simple closed surface has exactly one interior, no holes, and is hollow. A sphere is the set of all points at a given distance from a given point, the center . A sphere is a simple closed surface. A solid is a simple closed surface with all interior points. (see p. 726) A polyhedron is a simple closed surface made up of polygonal regions, or faces . The vertices of the polygonal regions are the vertices of the polyhedron, and the sides of each polygonal region are the edges of the polyhedron. (see p. 726-727) A prism is a polyhedron in which two congruent faces lie in parallel planes and the other faces are bounded by parallelograms. The parallel faces of a prism are the bases of the prism. A prism is usually names after its bases. The faces other than the bases are the lateral faces of a prism. A right prism is one in which the lateral faces are all bounded by rectangles. An oblique prism is one in which some of the lateral faces are not bounded by rectangles. To draw a prism: 1) Draw one of the bases. 2) Draw vertical segments of equal length from each vertex. 3) Connect the bottom endpoints to form the second base. Use dashed segments for edges that cannot be seen. A pyramid is a polyhedron determined by a polygon and a point not in the plane of the polygon. The pyramid consists of the triangular regions determined by the point and each pair of consecutive vertices of the polygon and the polygonal region determined by the polygon. -

The Truncated Icosahedron As an Inflatable Ball

https://doi.org/10.3311/PPar.12375 Creative Commons Attribution b |99 Periodica Polytechnica Architecture, 49(2), pp. 99–108, 2018 The Truncated Icosahedron as an Inflatable Ball Tibor Tarnai1, András Lengyel1* 1 Department of Structural Mechanics, Faculty of Civil Engineering, Budapest University of Technology and Economics, H-1521 Budapest, P.O.B. 91, Hungary * Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] Received: 09 April 2018, Accepted: 20 June 2018, Published online: 29 October 2018 Abstract In the late 1930s, an inflatable truncated icosahedral beach-ball was made such that its hexagonal faces were coloured with five different colours. This ball was an unnoticed invention. It appeared more than twenty years earlier than the first truncated icosahedral soccer ball. In connection with the colouring of this beach-ball, the present paper investigates the following problem: How many colourings of the dodecahedron with five colours exist such that all vertices of each face are coloured differently? The paper shows that four ways of colouring exist and refers to other colouring problems, pointing out a defect in the colouring of the original beach-ball. Keywords polyhedron, truncated icosahedron, compound of five tetrahedra, colouring of polyhedra, permutation, inflatable ball 1 Introduction Spherical forms play an important role in different fields – not even among the relics of the Romans who inherited of science and technology, and in different areas of every- many ball games from the Greeks. day life. For example, spherical domes are quite com- The Romans mainly used balls composed of equal mon in architecture, and spherical balls are used in most digonal panels, forming a regular hosohedron (Coxeter, 1973, ball games. -

Arxiv:1705.01294V1

Branes and Polytopes Luca Romano email address: [email protected] ABSTRACT We investigate the hierarchies of half-supersymmetric branes in maximal supergravity theories. By studying the action of the Weyl group of the U-duality group of maximal supergravities we discover a set of universal algebraic rules describing the number of independent 1/2-BPS p-branes, rank by rank, in any dimension. We show that these relations describe the symmetries of certain families of uniform polytopes. This induces a correspondence between half-supersymmetric branes and vertices of opportune uniform polytopes. We show that half-supersymmetric 0-, 1- and 2-branes are in correspondence with the vertices of the k21, 2k1 and 1k2 families of uniform polytopes, respectively, while 3-branes correspond to the vertices of the rectified version of the 2k1 family. For 4-branes and higher rank solutions we find a general behavior. The interpretation of half- supersymmetric solutions as vertices of uniform polytopes reveals some intriguing aspects. One of the most relevant is a triality relation between 0-, 1- and 2-branes. arXiv:1705.01294v1 [hep-th] 3 May 2017 Contents Introduction 2 1 Coxeter Group and Weyl Group 3 1.1 WeylGroup........................................ 6 2 Branes in E11 7 3 Algebraic Structures Behind Half-Supersymmetric Branes 12 4 Branes ad Polytopes 15 Conclusions 27 A Polytopes 30 B Petrie Polygons 30 1 Introduction Since their discovery branes gained a prominent role in the analysis of M-theories and du- alities [1]. One of the most important class of branes consists in Dirichlet branes, or D-branes. D-branes appear in string theory as boundary terms for open strings with mixed Dirichlet-Neumann boundary conditions and, due to their tension, scaling with a negative power of the string cou- pling constant, they are non-perturbative objects [2].