Neurodiversity in Relation: an Artistic Intraethnography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Life and Times Of'asperger's Syndrome': a Bakhtinian Analysis Of

The life and times of ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’: A Bakhtinian analysis of discourses and identities in sociocultural context Kim Davies Bachelor of Education (Honours 1st Class) (UQ) Graduate Diploma of Teaching (Primary) (QUT) Bachelor of Social Work (UQ) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2015 The School of Education 1 Abstract This thesis is an examination of the sociocultural history of ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’ in a Global North context. I use Bakhtin’s theories (1919-21; 1922-24/1977-78; 1929a; 1929b; 1935; 1936-38; 1961; 1968; 1970; 1973), specifically of language and subjectivity, to analyse several different but interconnected cultural artefacts that relate to ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’ and exemplify its discursive construction at significant points in its history, dealt with chronologically. These sociocultural artefacts are various but include the transcript of a diagnostic interview which resulted in the diagnosis of a young boy with ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’; discussion board posts to an Asperger’s Syndrome community website; the carnivalistic treatment of ‘neurotypicality’ at the parodic website The Institute for the Study of the Neurologically Typical as well as media statements from the American Psychiatric Association in 2013 announcing the removal of Asperger’s Syndrome from the latest edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-5 (APA, 2013). One advantage of a Bakhtinian framework is that it ties the personal and the sociocultural together, as inextricable and necessarily co-constitutive. In this way, the various cultural artefacts are examined to shed light on ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’ at both personal and sociocultural levels, simultaneously. -

Gesnerus 2020-2.Indb

Gesnerus 77/2 (2020) 279–311, DOI: 10.24894/Gesn-de.2020.77012 Vom «autistischen Psychopathen» zum Autismusspektrum. Verhaltensdiagnostik und Persönlichkeitsbehauptung in der Geschichte des Autismus Rüdiger Graf Abstract Der Aufsatz untersucht das Verhältnis von Persönlichkeit und Verhalten in der Defi nition und Diagnostik des Autismus von Kanner und Asperger in den 1940er Jahren bis in die neueren Ausgaben des DSM und ICD. Dazu unter- scheidet er drei verschiedene epistemische Zugänge zum Autismus: ein exter- nes Wissen der dritten Person, das über Verhaltensbeobachtungen, Testver- fahren und Elterninterviews gewonnen wird; ein stärker praktisches Wissen der zweiten Person, das in der andauernden, alltäglichen Interaktion bei El- tern und Betreuer*innen entsteht, und schließlich das introspektive Wissen der ersten Person, d.h. der Autist*innen selbst. Dabei resultiert die Kerndif- ferenz in der Behandlung des Autismus daraus, ob man meint, die Persönlich- keit eines Menschen allein über die Beobachtung von Verhaltensweisen er- schließen zu können oder ob es sich um eine vorgängige Struktur handelt, die introspektiv zugänglich ist, Verhalten prägt und ihm Sinn verleihen kann. Die Entscheidung hierüber führt zu grundlegend anderen Positionierungen zu verhaltenstherapeutischen Ansätzen, wie insbesondere zu Ole Ivar Lovaas’ Applied Behavior Analysis. Autismus; Psychiatriegeschichte; Wissensgeschichte; Verhaltenstherapie; Neurodiversität PD Dr. Rüdiger Graf, Leibniz-Zentrum für Zeithistorische Forschung Potsdam, Am Neuen Markt 1, 14467 Potsdam, [email protected]. Gesnerus 77 (2020) 279 Downloaded from Brill.com09/27/2021 01:45:02AM via free access «Autistic Psychopaths» and the Autism Spectrum. Diagnosing Behavior and Claiming Personhood in the History of Autism The article examines how understandings of personality and behavior have interacted in the defi nition and diagnostics of autism from Kanner and As- perger in the 1940s to the latest editions of DSM and ICD. -

AAC Technology, Autism, and the Empathic Turn

Delft University of Technology AAC Technology, Autism, and the Empathic Turn van Grunsven, Janna; Roeser, Sabine DOI 10.1080/02691728.2021.1897189 Publication date 2021 Document Version Final published version Published in Social Epistemology Citation (APA) van Grunsven, J., & Roeser, S. (2021). AAC Technology, Autism, and the Empathic Turn. Social Epistemology. https://doi.org/10.1080/02691728.2021.1897189 Important note To cite this publication, please use the final published version (if applicable). Please check the document version above. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download, forward or distribute the text or part of it, without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license such as Creative Commons. Takedown policy Please contact us and provide details if you believe this document breaches copyrights. We will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. This work is downloaded from Delft University of Technology. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to a maximum of 10. Social Epistemology A Journal of Knowledge, Culture and Policy ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tsep20 AAC Technology, Autism, and the Empathic Turn Janna van Grunsven & Sabine Roeser To cite this article: Janna van Grunsven & Sabine Roeser (2021): AAC Technology, Autism, and the Empathic Turn, Social Epistemology, DOI: 10.1080/02691728.2021.1897189 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/02691728.2021.1897189 © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group. -

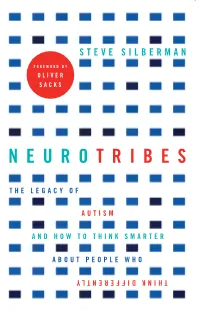

Neuro Tribes

NEURO SMARTER ABOUT PEOPLE WHO THE LEGACY OF ‘NeuroTribes is a sweeping and penetrating history, presented with a rare sympathy and sensitivity . it will change how you think of autism.’—From the foreword by Oliver Sacks STEVE SILBERMAN What is autism: a devastating developmental disorder, a lifelong FOREWORD BY disability, or a naturally occurring form of cognitive difference akin AUTISM to certain forms of genius? In truth, it is all of these things and more OLIVER —and the future of our society depends on our understanding it. TRIBES SACKS Following on from his ground breaking article ‘The Geek Syndrome’, AND HOW TO THINK Wired reporter Steve Silberman unearths the secret history of autism, THINK DIFFERENTLY long suppressed by the same clinicians who became famous for identifying it, and discovers why the number of diagnoses has soared in recent years. Going back to the earliest autism research and chronicling the brave and lonely journey of autistic people and their families through the decades, Silberman provides long-sought solutions to the autism puzzle, while mapping out a path towards a more humane world in which people with learning differences have access to the resources they need to live happier and more meaningful lives. NEUROTRIBES He reveals the untold story of Hans Asperger, whose ‘little professors’ STEVE SILBERMAN were targeted by the darkest social-engineering experiment in human history; exposes the covert campaign by child psychiatrist Leo Kanner THE LEGACY OF to suppress knowledge of the autism spectrum for fifty years; and casts light on the growing movement of ‘neurodiversity’ activists seeking respect, accommodations in the workplace and education, and the right to self-determination for those with cognitive differences. -

L Brown Presentation

Health Equity Learning Series Beyond Service Provision and Disparate Outcomes: Disability Justice Informing Communities of Practice HEALTH EQUITY LEARNING SERIES 2016-17 GRANTEES • Aurora Mental Health Center • Northwest Colorado Health • Bright Futures • Poudre Valley Health System • Central Colorado Area Health Education Foundation (Vida Sana) Center • Pueblo Triple Aim Corporation • Colorado Cross-Disability Coalition • Rural Communities Resource Center • Colorado Latino Leadership, Advocacy • Southeast Mental Health Services and Research Organization • The Civic Canopy • Cultivando • The Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and • Eagle County Health and Human Transgender Community Center of Services Colorado • El Centro AMISTAD • Tri-County Health Network • El Paso County Public Health • Warm Cookies of the Revolution • Hispanic Affairs Project • Western Colorado Area Health Education Center HEALTH EQUITY LEARNING SERIES Lydia X. Z. Brown (they/them) • Activist, writer and speaker • Past President, TASH New England • Chairperson, Massachusetts Developmental Disabilities Council • Board member, Autism Women’s Network ACCESS NOTE Please use this space as you need or prefer. Sit in chairs or on the floor, pace, lie on the floor, rock, flap, spin, move around, step in and out of the room. CONTENT/TW I will talk about trauma, abuse, violence, and murder of disabled people, as well as forced treatment and institutions, and other acts of violence, including sexual violence. Please feel free to step out of the room at any time if you need to. BEYOND SERVICE -

Disability in an Age of Environmental Risk by Sarah Gibbons a Thesis

Disablement, Diversity, Deviation: Disability in an Age of Environmental Risk by Sarah Gibbons A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2016 © Sarah Gibbons 2016 I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This dissertation brings disability studies and postcolonial studies into dialogue with discourse surrounding risk in the environmental humanities. The central question that it investigates is how critics can reframe and reinterpret existing threat registers to accept and celebrate disability and embodied difference without passively accepting the social policies that produce disabling conditions. It examines the literary and rhetorical strategies of contemporary cultural works that one, promote a disability politics that aims for greater recognition of how our environmental surroundings affect human health and ability, but also two, put forward a disability politics that objects to devaluing disabled bodies by stigmatizing them as unnatural. Some of the major works under discussion in this dissertation include Marie Clements’s Burning Vision (2003), Indra Sinha’s Animal’s People (2007), Gerardine Wurzburg’s Wretches & Jabberers (2010) and Corinne Duyvis’s On the Edge of Gone (2016). The first section of this dissertation focuses on disability, illness, industry, and environmental health to consider how critics can discuss disability and environmental health in conjunction without returning to a medical model in which the term ‘disability’ often designates how closely bodies visibly conform or deviate from definitions of the normal body. -

Neurodiversity Studies

Neurodiversity Studies Building on work in feminist studies, queer studies, and critical race theory, this vol• ume challenges the universality of propositions about human nature, by questioning the boundaries between predominant neurotypes and ‘others’, including dyslexics, autistics, and ADHDers. This is the first work of its kind to bring cutting-edge research across disciplines to the concept of neurodiversity. It offers in-depth explorations of the themes of cure/ prevention/eugenics; neurodivergent wellbeing; cross-neurotype communication; neu• rodiversity at work; and challenging brain-bound cognition. It analyses the role of neuro-normativity in theorising agency, and a proposal for a new alliance between the Hearing Voices Movement and neurodiversity. In doing so, we contribute to a cultural imperative to redefine what it means to be human. To this end, we propose a new field of enquiry that finds ways to support the inclusion of neurodivergent perspectives in knowledge production, and which questions the theoretical and mythological assump• tions that produce the idea of the neurotypical. Working at the crossroads between sociology, critical psychology, medical humani• ties, critical disability studies, and critical autism studies, and sharing theoretical ground with critical race studies and critical queer studies, the proposed new field – neurodiversity studies – will be of interest to people working in all these areas. Hanna Bertilsdotter Rosqvist is an Associate Professor in Sociology and currently a Senior Lecturer in Social work at Södertörn University. Her recent research is around autism, identity politics, and sexual, gendered, and age normativity. She is the former Chief Editor of Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research. Nick Chown is a book indexer who undertakes autism research in his spare time. -

Download Decision

BEFORE THE OFFICE OF ADMINISTRATIVE HEARINGS STATE OF CALIFORNIA In the Consolidated Matters of: PARENT ON BEHALF OF STUDENT, OAH CASE NO. 2013080387 v. LAS VIRGENES UNIFIED SCHOOL DISTRICT, LAS VIRGENES UNIFIED SCHOOL OAH CASE NO. 2013071203 DISTRICT, v. PARENTS ON BEHALF OF STUDENT. DECISION Las Virgenes Unified School District (District) filed a Request for Due Process Hearing in OAH Case No. 2013071203 with the Office of Administrative Hearings (OAH), State of California, on July 29, 2013, naming Student. Student filed a Request for Due Process Hearing in OAH Case No. 2013080387 with OAH on August 8, 2013, naming District. OAH consolidated the matters on August 16, 2013, and ordered the 45-day timeline for issuance of the decision to be based on the date the complaint was filed in Student‟s case (OAH Case Number 2013080387). OAH continued the consolidated matter for good cause on September 6, 2013. June R. Lehrman, Administrative Law Judge (ALJ), heard this matter on October 28- 31, 2013, and November 4-6, 2013, in Calabasas, California. Jane DuBovy, Attorney at Law, and Carolina Watts, educational advocate, represented Parents and Student (collectively, Student). Student‟s mother (Mother) attended the hearing on all days. Student‟s father (Father) attended the hearing on October 28, November 4, and November 5, 2013. 1 Wesley B. Parsons and Siobhan H. Cullen, Attorneys at Law, appeared on behalf of District. Mary Schillinger, Assistant Superintendent, and Sahar Barsoum, Coordinator of Special Education, attended the hearing on all days. On the last day of hearing, a continuance was granted for the parties to file written closing arguments and the record remained open until November 20, 2013. -

The Impact of a Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder on Nonmedical Treatment Options in the Learning Environment from the Perspectives of Parents and Pediatricians

St. John Fisher College Fisher Digital Publications Education Doctoral Ralph C. Wilson, Jr. School of Education 12-2017 The Impact of a Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder on Nonmedical Treatment Options in the Learning Environment from the Perspectives of Parents and Pediatricians Cecilia Scott-Croff St. John Fisher College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/education_etd Part of the Education Commons How has open access to Fisher Digital Publications benefited ou?y Recommended Citation Scott-Croff, Cecilia, "The Impact of a Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder on Nonmedical Treatment Options in the Learning Environment from the Perspectives of Parents and Pediatricians" (2017). Education Doctoral. Paper 341. Please note that the Recommended Citation provides general citation information and may not be appropriate for your discipline. To receive help in creating a citation based on your discipline, please visit http://libguides.sjfc.edu/citations. This document is posted at https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/education_etd/341 and is brought to you for free and open access by Fisher Digital Publications at St. John Fisher College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Impact of a Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder on Nonmedical Treatment Options in the Learning Environment from the Perspectives of Parents and Pediatricians Abstract The purpose of this qualitative study was to identify the impact of a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder on treatment options available, within the learning environment, at the onset of a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) from the perspective of parents and pediatricians. Utilizing a qualitative methodology to identify codes, themes, and sub-themes through semi-structured interviews, the research captures the lived experiences of five parents with children on the autism spectrum and five pediatricians who cared for those children and families. -

The Joy of Autism: Part 2

However, even autistic individuals who are profoundly disabled eventually gain the ability to communicate effectively, and to learn, and to reason about their behaviour and about effective ways to exercise control over their environment, their unique individual aspects of autism that go beyond the physiology of autism and the source of the profound intrinsic disabilities will come to light. These aspects of autism involve how they think, how they feel, how they express their sensory preferences and aesthetic sensibilities, and how they experience the world around them. Those aspects of individuality must be accorded the same degree of respect and the same validity of meaning as they would be in a non autistic individual rather than be written off, as they all too often are, as the meaningless products of a monolithically bad affliction." Based on these extremes -- the disabling factors and atypical individuality, Phil says, they are more so disabling because society devalues the atypical aspects and fails to accommodate the disabling ones. That my friends, is what we are working towards -- a place where the group we seek to "help," we listen to. We do not get offended when we are corrected by the group. We are the parents. We have a duty to listen because one day, our children may be the same people correcting others tomorrow. In closing, about assumptions, I post the article written by Ann MacDonald a few days ago in the Seattle Post Intelligencer: By ANNE MCDONALD GUEST COLUMNIST Three years ago, a 6-year-old Seattle girl called Ashley, who had severe disabilities, was, at her parents' request, given a medical treatment called "growth attenuation" to prevent her growing. -

Introduction Contents

Select Committee on Autism, Department of the Senate, Parliament House, Canberra, ACT 2600. To the Committee, Introduction My name is David Cameron Staples. I am a son, a husband, a father, a professional worker in IT, I have lived in Melbourne my whole life, and I am on the Autism spectrum. Or, as we autists tend to prefer, I am “autistic”. Since I received my Asperger’s Syndrome diagnosis in 2010 at the age of 37, I have been reconciling myself with this new revealed identity, relearning how to better manage myself and my relations with others, and, over the last few years, attempting to advance the cause of Autism advocacy and access in my workplace at the University of Melbourne. Please note that what follows is based on my own experience and understanding. I am not a researcher (although I do make an effort to stay abreast of the research), and I do not speak for the University of Melbourne. I speak as an advocate for myself, and for my autistic kin, including those who aren’t so lucky as to be able to speak on their own behalf, easily or at all. I have tried to highlight key points below by bolding the main point and applying callout marks in the margins, as in this paragraph. I would make more recommendations for where to go next, but I think the main problem is that either we still don’t understand the question well enough yet, or else that it’s blindingly obvious what the answer is, but no-one’s done anything to implement it yet. -

The Stone Age Origins of Autism

Chapter 1 The Stone Age Origins of Autism Penny Spikins Additional information is available at the end of the chapter http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/53883 ‘Their strengths and deficits do not deny them humanity but, rather, shape their humanity’ Grinker 2010: 173 [in [1]] © 2013 Spikins; licensee InTech. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. 4 Recent Advances in Autism Spectrum Disorders - Volume II 1. Introduction 1.1. Minds from a stone age past Our modern societies have been said to house ‘stone age minds’ (see [2]). That is to say that despite all the influences of modern culture our hard wired neurological make-up, instinc‐ tive responses and emotional capacities evolved in the vast depths of time which make up our evolutionary past. Much of what makes us ‘human’ thus rests on the nature of societies in the depths of prehistory thousands or even millions of years ago. Looking back on the archaeological record of the early stone age there is much to be proud of in our ancestry. Not only our remarkable intelligence but also our deep capacities to care about others and work together for a common good come from evolutionary selection on early humans throughout millions of years of the stone age. As far back as 1.6 million years ago we have archaeological evidence from survival of illnesses and trauma that those who were ill were looked after by others, and by the time of Neanderthals extensive care of the ill, infirm and elderly was common, see [3,4].