Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neoplatonism: the Last Ten Years

The International Journal The International Journal of the of the Platonic Tradition 9 (2015) 205-220 Platonic Tradition brill.com/jpt Critical Notice ∵ Neoplatonism: The Last Ten Years The past decade or so has been an exciting time for scholarship on Neo platonism. I ought to know, because during my stint as the author of the “Book Notes” on Neoplatonism for the journal Phronesis, I read most of what was published in the field during this time. Having just handed the Book Notes over to George BoysStones, I thought it might be worthwhile to set down my overall impressions of the state of research into Neoplatonism. I cannot claim to have read all the books published on this topic in the last ten years, and I am here going to talk about certain themes and developments in the field rather than trying to list everything that has appeared. So if you are an admirer, or indeed author, of a book that goes unmentioned, please do not be affronted by this silence—it does not necessarily imply a negative judgment on my part. I hope that the survey will nonetheless be wideranging and comprehensive enough to be useful. I’ll start with an observation made by Richard Goulet,1 which I have been repeating to students ever since I read it. Goulet conducted a statistical analy sis of the philosophical literature preserved in the original Greek, and discov ered that almost threequarters of it (71%) was written by Neoplatonists and commentators on Aristotle. In a sense this should come as no surprise. -

B Philosophy (General) B

B PHILOSOPHY (GENERAL) B Philosophy (General) For general philosophical treatises and introductions to philosophy see BD10+ Periodicals. Serials 1.A1-.A3 Polyglot 1.A4-Z English and American 2 French and Belgian 3 German 4 Italian 5 Spanish and Portuguese 6 Russian and other Slavic 8.A-Z Other. By language, A-Z Societies 11 English and American 12 French and Belgian 13 German 14 Italian 15 Spanish and Portuguese 18.A-Z Other. By language, A-Z 20 Congresses Collected works (nonserial) 20.6 Several languages 20.8 Latin 21 English and American 22 French and Belgian 23 German 24 Italian 25 Spanish and Portuguese 26 Russian and other Slavic 28.A-Z Other. By language, A-Z 29 Addresses, essays, lectures Class here works by several authors or individual authors (31) Yearbooks see B1+ 35 Directories Dictionaries 40 International (Polyglot) 41 English and American 42 French and Belgian 43 German 44 Italian 45 Spanish and Portuguese 48.A-Z Other. By language, A-Z Terminology. Nomenclature 49 General works 50 Special topics, A-Z 51 Encyclopedias 1 B PHILOSOPHY (GENERAL) B Historiography 51.4 General works Biography of historians 51.6.A2 Collective 51.6.A3-Z Individual, A-Z 51.8 Pictorial works Study and teaching. Research Cf. BF77+ Psychology Cf. BJ66+ Ethics Cf. BJ66 Ethics 52 General works 52.3.A-Z By region or country, A-Z 52.5 Problems, exercises, examinations 52.65.A-Z By school, A-Z Communication of information 52.66 General works 52.67 Information services 52.68 Computer network resources Including the Internet 52.7 Authorship Philosophy. -

BIBLIOGRAPHY for a New Edition of ARISTOTLE's PROTREPTICUS

1 PROVISIONAL BIBLIOGRAPHY for a new edition of ARISTOTLE'S PROTREPTICUS compiled by D. S. Hutchinson and Monte Ransome Johnson version of 2013 February 25 A. Primary Sources 1. Aristotle a. Collections of fragments of Aristotle's lost works, including his Protrepticus b. Editions and translations of fragments of Aristotle’s Protrepticus c. Editions and translations of papyri attributable to Aristotle's Protrepticus d. Editions and translations of the Aristotle Corpus e. Editions and translations of other lost works of Aristotle 2. Isocrates 3. Plato 4. Archytas of Tarentum 5. Heraclides of Pontus 6. Anonymous Iamblichi 7. Cicero 8. Clement of Alexandria (AD II-III) 9. Lactantius (AD III-IV) 10. Iamblichus of Chalcis (AD III-IV) a. Manuscripts of the Protrepticus b. Printed editions and translations of the Protrepticus c. Editions and translations of other works of Iamblichus 11. Ancient Commentators a. Aristocles of Messene (AD I) b. Alexander of Aphrodisias (AD II) c. Ammonius (AD V) d. Proclus (AD V) e. Olympiodorus the younger (AD V-VI) f. Philoponus (AD VI) g. Asclepius of Tralles (AD VI) h. Elias (AD VI-VII) i. David the Invincible Philosopher (AD VI-VII) j. Anonymous Scholion on Cod.Par.Gr.2064 12. Boethius (AD V-VI) 13. Stobaeus (AD VI) B. Secondary Sources (arranged alphabetically) 2 A. Primary Sources 1. Aristotle a. Collections of fragments of Aristotle's lost works, including his Protrepticus Flashar, H. Aristoteles: Fragmente zu Philosophie, Rhetorik, Poetik, Dictung. Darmstadt, 2006. Gigon, O. Librorum deperditorum fragmenta = vol. iii of Aristoteles Opera. Berlin, 1987. Gohlke, P. Aristoteles Fragmente. Paderborn, 1959. -

Idea Xxix/1 2017

Rada Redakcyjna: Mira Czarnawska (Warszawa), Zbigniew Kaźmierczak (Białystok), Andrzej Kisielewski (Białystok), Jerzy Kopania (Białystok), Małgorzata Kowalska (Białystok), Dariusz Kubok (Katowice) Rada Naukowa: Adam Drozdek, PhD Associate Professor, Duquesne University, Pittsburgh, USA Anna Grzegorczyk, prof. dr hab., Uniwersytet Adama Mickiewicza w Poznaniu Vladimír Leško, Prof. PhDr., Uniwersytet Pavla Jozefa Šafárika w Koszycach, Słowacja Marek Maciejczak, prof. dr hab., Wydział Administracji i Nauk Społecznych, Politechnika Warszawska Artur Malinovsky, dr, Odeski Narodowy Uniwersytet im. Ilii Miecznnikowa, Ukraina David Ost, Joseph DiGangi Professor of Political Science, Hobart and William Smith Colleges, Geneva, New York, USA Teresa Pękala, prof. dr hab., UMCS w Lublinie Swietłana Suchariewa, dr hab., Wschodnioeuropejski Uniwersytet Narodowy im. Łesi Ukrainki w Łucku, Ukraina Tahir Uluç, PhD Associate Professor, Necmettin Erbakan Üniversites, iİlahiyat Fakültesi, Wydział Teologii, Konya, Turcja Recenzenci: Vladimír Leško, Prof. PhDr. Jacek Breczko, dr. hab. Andrzej Noras, prof. dr hab. Tahir Uluç, PhD Associate Professor Redakcja: dr hab. Sławomir Raube (redaktor naczelny) dr Daniel Karczewski, mgr Karol Więch (sekretarze) dr hab. Dariusz Kulesza, prof. UwB (redaktor językowy) dr Kirk Palmer (redaktor językowy, native speaker) Korekta: Zespół Projekt okładki i strony tytułowej: Tomasz Czarnawski Redakcja techniczna: Ewa Frymus-Dąbrowska ADRES REDAKCJI: Uniwersytet w Białymstoku Plac Uniwersytecki 1 15-420 Białystok e-mail: [email protected] http://filologia.uwb.edu.pl/idea/idea.htm ISSN 0860–4487 © Copyright by Uniwersytet w Białymstoku, Białystok 2017 Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu w Białymstoku 15–097 Białystok, ul. Marii Skłodowskiej-Curie 14, tel. 857457120 http://wydawnictwo.uwb.edu.pl, e-mail: [email protected] Skład, druk i oprawa: Wydawnictwo PRYMAT, Mariusz Śliwowski, ul. Hetmańska 42, 15-727 Białystok, tel. -

2:00-4:00 Pm Session 1A: Theandrites: Byzantine Philosophy

Thursday, June 10, 2021 (All times are in the time zone of Athens.) 2:00-4:00 p.m. Session 1a: Theandrites: Byzantine Philosophy and Christian Platonism Frederick Laurtizen <[email protected]> and Sarah Klitenic Wear <[email protected]> Panagiotis Pavlos <[email protected]>, University of Oslo, Platonism and Christian Thought: A System in Phase Transition; An Approach to the Contributions of Vassilios Tatakis and fr. John Romanides” Fernandez Marco Alviz <[email protected]>, National University of Distance Learning, UNED, Madrid, “Χάρισμα and παιδεία in Late Antiquity: From Neoplatonic circles to Christian thought in the 3rd and 4th centuries” Chris Chris Barnard <[email protected]>, Newman University, “The Good and Evil λόγοι Dialectic in Saint Maximus the Confessor” Evi Zacharia <[email protected]>, Radboud University Nijmegen, “Commentary on Alcibiades I: towards an explanation of human perfection through love” Session 1b: Plotinus and Proclus Marcin Podbielski <[email protected]> Paolo Di Leo <[email protected]>, Singapore University of Technology and Design, “Plotinus and Heidegger: A Dialogue Through Parmenides’ R. B3” Marcin Podbielski <[email protected]>, Jesuit University Ignatianum, “Revisiting the Text, Grammar, and Translations of Plotinus’s On Contemplation” Martin Lee Mueller <[email protected]>, University of Oslo, “Deep Ecology and Telling About Nature” Zdenek Lenner, <[email protected]>, École Pratique des Hautes -

The Armenians the Peoples of Europe

The Armenians The Peoples of Europe General Editors James Campbell and Barry Cunliffe This series is about the European tribes and peoples from their origins in prehistory to the present day. Drawing upon a wide range of archaeolo gical and historical evidence, each volume presents a fresh and absorbing account of a group’s culture, society and usually turbulent history. Already published The Etruscans The Franks Graeme Barker and Thomas Edward James Rasmussen The Russians The Lombards Robin Milner-Gulland Neil Christie The Mongols The Basques David Morgan Roger Collins The Armenians The English A.E. Redgate Geoffrey Elton The Huns The Gypsies E. A. Thompson Angus Fraser The Early Germans The Bretons Malcolm Todd Patrick Galliou and Michael Jones The Illyrians The Goths John Wilkes Peter Heather In preparation The Sicilians The Spanish David Abulafia Roger Collins The Irish The Romans Francis John Byrne and Michael Timothy Cornell Herity The Celts The Byzantines David Dumville Averil Cameron The Scots The First English Colin Kidd Sonia Chadwick Hawkes The Ancient Greeks The Normans Brian Sparkes Marjorie Chibnall The Piets The Serbs Charles Thomas Sima Cirkovic The Armenians A. E. Redgate Copyright © Anne Elizabeth Redgate 1998,2000 The right of Anne Elizabeth Redgate to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 1998 First published in paperback 2000 2468 10975 3 1 Blackwell Publishers Ltd 108 Cowley Road Oxford OX4 1JF Blackwell Publishers Inc. 350 Main Street Malden, Massachusetts 02148 USA All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. -

Who Is David the Invincible Philosopher?

Who is David the Invincible Philosopher? To know wisdom and instruction; to perceive the words of understanding Proverbs 1:2 Famously, this verse from the beginning of the Book of Proverbs was the first thing written down in the newly invented Armenian alphabet. Wisdom, imasdutyun, is the root of the word for philosophy in Armenian, imasdasirutyun, which directly reflects the Greek, meaning “love of wisdom.” After the creation of the Armenian alphabet by Mesrob Masdotz in 405 AD, his students produced a flurry of translation into Armenian. It is this activity of learned translation of edifying works into Armenian that the Armenian Church celebrates this Saturday. We recall the “Holy Translators,” a list that includes Mesrob himself, early writers and translators such as Yeghishe (who wrote the history of St. Vartan), as well as later translators such as Nersess Shnorhali. Among the list of Holy Translators we commemorate this Saturday is one “David the Philosopher.” While his title of philosopher, a lover of wisdom, points to that first moment of translation into Armenian and provides us with a glimpse of the goals and objectives of those translators, he is not as well known a figure as Masdotz, Yeghishe, or Shnorhali. Who is “David the Philosopher,” and why is a philosopher recognized as a holy translator? Often called “David the Invincible Philosopher,” the figure of David is best known through his texts, which became absolutely central to Armenian literary and philosophical history. He has left us four major texts: two translations and commentaries on works of Aristotle (Categories and Analytics), a commentary on the neo-Platonist philosopher Porphyry’s Isagoge, and perhaps his most well-known work, Definitions and Divisions of Philosophy. -

Library of Congress Classification

B PHILOSOPHY (GENERAL) B Philosophy (General) For general philosophical treatises and introductions to philosophy see BD10+ Periodicals. Serials 1.A1-.A3 Polyglot 1.A4-Z English and American 2 French and Belgian 3 German 4 Italian 5 Spanish and Portuguese 6 Russian and other Slavic 8.A-Z Other. By language, A-Z Societies 11 English and American 12 French and Belgian 13 German 14 Italian 15 Spanish and Portuguese 18.A-Z Other. By language, A-Z 20 Congresses Collected works (nonserial) 20.6 Several languages 20.8 Latin 21 English and American 22 French and Belgian 23 German 24 Italian 25 Spanish and Portuguese 26 Russian and other Slavic 28.A-Z Other. By language, A-Z 29 Addresses, essays, lectures Class here works by several authors or individual authors (31) Yearbooks see B1+ 35 Directories Dictionaries 40 International (Polyglot) 41 English and American 42 French and Belgian 43 German 44 Italian 45 Spanish and Portuguese 48.A-Z Other. By language, A-Z Terminology. Nomenclature 49 General works 50 Special topics, A-Z 51 Encyclopedias Historiography 51.4 General works Biography of historians 51.6.A2 Collective 51.6.A3-Z Individual, A-Z 51.8 Pictorial works Study and teaching. Research Cf. BF77+ Psychology Cf. BJ66+ Ethics Cf. BJ66 Ethics 52 General works 1 B PHILOSOPHY (GENERAL) B Study and teaching. Research -- Continued 52.3.A-Z By region or country, A-Z 52.5 Problems, exercises, examinations 52.65.A-Z By school, A-Z Communication of information 52.66 General works 52.67 Information services 52.68 Computer network resources Including the Internet 52.7 Authorship Philosophy. -

The Council of Chalcedon and the Armenian Church

THE COUNCIL OF CHALCEDON AND THE ARMENIAN CHURCH KAREKIN SARKISSIAN Prelate, Armenian Apostolic Church of America A PUBLICATION OF The Armenian Church Prelacy NEW YORK Copyright© 1965 by Archbishop Karekin Sarkissian Preface to the Second Edition Copyright © 1975 by The Armenian Apostolic Church of America Ail rights reserved Printed in U.S.A. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Sarkissian, Karekin, Bp. The Council of Chalccdon and the Armenian Church. Bibliography: p. Includes indexes. i. Armenian Church. 2. Chalccdon, Council of, 451. I. Title. S25 1975 28i'.62 75-28381 To the beloved memory of His Holiness ZAREHI Catholicos of the Great House of Cilicia (1915-1963) In. humble recognition of his sacrifice for the Armenian Church and Nation CONTENTS page FOREWORD xi MAPS I Armenia in the fourth and fifth centuries xiv il Christianity in Syria and Mesopotamia in the fifth and sixth centuries xv EXPLANATORY NOTES xvii INTRODUCTION i The Problem and its Significance i n The Traditional View 6 in Recent Critical Approach 14 1. CHALCEDON AFTER CHALCEDON i Some Significant Aspects of the Council of Chalcedon 25 n Some Aspects of Post-Chalcedonian History 47 2. THE HISTORICAL BACKGROUND (i): The Political Situation 61 3. THE HISTORICAL BACKGROUND (2): The Ecclesiastical Situation Before the Council of Ephesus 75 i The First Four Centuries 76 n The First Three Decades of the Fourth Century 85 4. THE HISTORICAL BACKGROUND (3): The Ecclesiastical Situation between the Council of Ephesus and the Council of Chalcedon 111 5. THE HISTORICAL BACKGROUND (4) The Ecclesiastical Situation after the Council of Chalcedon 148 6. -

Gohar Muradyan, David the Invincible Commentary on Porphyry's Isagoge

62 Reviews Gohar Muradyan, David the Invincible Commentary on Porphyry’s Isagoge: Old Armenian Text with the Greek Original, an English Translation, Introduc- tion and Notes, Philosophia Antiqua, 137 (Leiden: Brill, 2015). ISBN 978-9- 004280847, e-ISBN 978-9-004280885, 205€. The mysterious David Anhałt, the Invincible Philosopher whose work is one of the only works of literature from the sixth century that could arguably be called ‘Armenian’. About David himself we know almost nothing at all— only that he was probably a pupil of Olympiodorus in Alexandria, and that he gave lectures on philosophy, versions of four of which have come down to us. These include a prolegomena known as the ‘Definitions and Divisions of Philosophy’, a commentary on the Isagogē of Porphyry, and commentaries on two works of Aristotle, the Categories and the Prior Analytics. These works appear to have circulated originally in Greek, but Armenian versions appeared soon afterward amid a wave of late sixth-century translations of Greek philo- sophical works. David’s connection to Armenia can only be established on the basis of the attention that his works received and on the strong tradition that arose in medieval times claiming him as one of his own. According to this tradition he was from the village of Nergin in Tarōn, a fact either giving rise to or derived from the toponymic ‘Nerginacʿi’ by which he is occasionally known. He is usually named as a pupil of Maštocʿ, the creator of the Armenian alphabet in the early fifth century, but has also been called a pupil of Movsēs Xorenacʿi, the historian known as the ‘father of Armenian history’ and whose own biog- raphy and era remains a matter of dispute. -

Michael B. Papazian: Curriculum Vitae

Michael B. Papazian Department of Religion and Philosophy Phone: (706) 346-5311 Berry College Fax: (706) 236-5091 Box 550 Email: [email protected] 2277 Martha Berry Highway Homepage: http://sites.berry.edu/mpapazian Mt. Berry, GA 30149 http://berry.academia.edu/MichaelPapazian/ Areas of Specialization Ancient philosophy, medieval Armenian theology, philosophical logic Areas of Interest and Competence Medieval philosophy, metaphysics, philosophy of law Education Ph.D. Philosophy, University of Virginia, 1995 M.St. Classical Armenian, Oxford University, 1995 M.A. Philosophy, University of Virginia, 1991 B.A. German and Philosophy, Johns Hopkins University, 1987 Employment Professor of Philosophy, Berry College, 2010-Present Associate Professor of Philosophy, Berry College, 2004-2010 Assistant Professor of Philosophy, Berry College, 1998-2004 Visiting Assistant Professor of Philosophy, Hampden-Sydney College, 1997-1998 Visiting Instructor of Philosophy, University of Virginia, 1996-1997 Adjunct Lecturer in Philosophy, St. Peter's College, 1995-1996 Administrative Positions Acting Chair, Department of Religion and Philosophy, Berry College, August 2014-January 2015 Chair, Philosophy Department Search Committee, Berry College, August 2013- February 2014 Chair, Berry College General Education Review Task Force, August 2009- May 2013 Chair, Department of Religion and Philosophy, Berry College, August 2004-December 2010 Interim Director, Berry College Honors Program, Fall 2005 Director, Berry College Honors Program, August 2001-May 2004 Assistant Director, Berry College Honors Program, August 2000- May 2001 Michael B. Papazian 2 Publications Books Step`anos Siwnets`i: Commentary on the four evangelists. New York: SIS Publications, 2014 Light from Light: An introduction to the history and theology of the Armenian Church. New York: SIS Publiciations, 2006 Commentary on Genesis by Eghishe. -

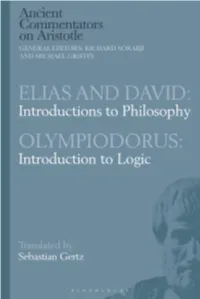

"Introductions to Philosophy" with Olympiodorus

E l i a s a n d D a v i d Introductions to Philosophy with Olympiodorus Introduction to Logic i Ancient Commentators on Aristotle GENERAL EDITORS : Richard Sorabji, Honorary Fellow, Wolfson College, University of Oxford, and Emeritus Professor, King’s College London, UK ; and Michael Griffi n, Assistant Professor, Departments of Philosophy and Classics, University of British Columbia, Canada. Th is prestigious series translates the extant ancient Greek philosophical commentaries on Aristotle. Written mostly between 200 and 600 AD , the works represent the classroom teaching of the Aristotelian and Neoplatonic schools in a crucial period during which pagan and Christian thought were reacting to each other. Th e translation in each volume is accompanied by an introduction, comprehensive commentary notes, bibliography, glossary of translated terms and a subject index. Making these key philosophical works accessible to the modern scholar, this series fi lls an important gap in the history of European thought. A webpage for the Ancient Commentators Project is maintained at ancientcommentators.org.uk and readers are encouraged to consult the site for details about the series as well as for addenda and corrigenda to published volumes. ii Elias and David Introductions to Philosophy with Olympiodorus Introduction to Logic T r a n s l a t e d b y S e b a s t i a n G e r t z BLOOMSBURY ACADEMIC Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY ACADEMIC and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain 2018 Copyright © Sebastian Gertz, 2018 Sebastian Gertz has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identifi ed as Editor of this work.