African Mathematics 1 Running Head

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

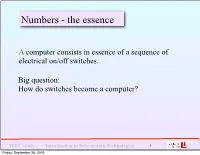

Numbers - the Essence

Numbers - the essence A computer consists in essence of a sequence of electrical on/off switches. Big question: How do switches become a computer? ITEC 1000 Introduction to Information Technologies 1 Friday, September 25, 2009 • A single switch is called a bit • A sequence of 8 bits is called a byte • Two or more bytes are often grouped to form word • Modern laptop/desktop standardly will have memory of 1 gigabyte = 1,000,000,000 bytes ITEC 1000 Introduction to Information Technologies 2 Friday, September 25, 2009 Question: How do encode information with switches ? Answer: With numbers - binary numbers using only 0’s and 1’s where for each switch on position = 1 off position = 0 ITEC 1000 Introduction to Information Technologies 3 Friday, September 25, 2009 • For a byte consisting of 8 bits there are a total of 28 = 256 ways to place 0’s and 1’s. Example 0 1 0 1 1 0 1 1 • For each grouping of 4 bits there are 24 = 16 ways to place 0’s and 1’s. • For a byte the first and second groupings of four bits can be represented by two hexadecimal digits • this will be made clear in following slides. ITEC 1000 Introduction to Information Technologies 4 Friday, September 25, 2009 Bits & Bytes imply creation of data and computer analysis of data • storing data (reading) • processing data - arithmetic operations, evaluations & comparisons • output of results ITEC 1000 Introduction to Information Technologies 5 Friday, September 25, 2009 Numeral systems A numeral system is any method of symbolically representing the counting numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, . -

On the Origin of the Indian Brahma Alphabet

- ON THE <)|{I<; IN <>F TIIK INDIAN BRAHMA ALPHABET GEORG BtfHLKi; SECOND REVISED EDITION OF INDIAN STUDIES, NO III. TOGETHER WITH TWO APPENDICES ON THE OKU; IN OF THE KHAROSTHI ALPHABET AND OF THK SO-CALLED LETTER-NUMERALS OF THE BRAHMI. WITH TIIKKK PLATES. STRASSBUKi-. K A K 1. I. 1 1M I: \ I I; 1898. I'lintccl liy Adolf Ilcil/.haiisi'ii, Vicniiii. Preface to the Second Edition. .As the few separate copies of the Indian Studies No. Ill, struck off in 1895, were sold very soon and rather numerous requests for additional ones were addressed both to me and to the bookseller of the Imperial Academy, Messrs. Carl Gerold's Sohn, I asked the Academy for permission to issue a second edition, which Mr. Karl J. Trlibner had consented to publish. My petition was readily granted. In addition Messrs, von Holder, the publishers of the Wiener Zeitschrift fur die Kunde des Morgenlandes, kindly allowed me to reprint my article on the origin of the Kharosthi, which had appeared in vol. IX of that Journal and is now given in Appendix I. To these two sections I have added, in Appendix II, a brief review of the arguments for Dr. Burnell's hypothesis, which derives the so-called letter- numerals or numerical symbols of the Brahma alphabet from the ancient Egyptian numeral signs, together with a third com- parative table, in order to include in this volume all those points, which require fuller discussion, and in order to make it a serviceable companion to the palaeography of the Grund- riss. -

Texts in Transit in the Medieval Mediterranean

Texts in Transit in the medieval mediterranean Edited by Y. Tzvi Langermann and Robert G. Morrison Texts in Transit in the Medieval Mediterranean Texts in Transit in the Medieval Mediterranean Edited by Y. Tzvi Langermann and Robert G. Morrison Th e Pennsylvania State University Press University Park, Pennsylvania This book has been funded in part by the Minerva Center for the Humanities at Tel Aviv University and the Bowdoin College Faculty Development Committee. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Langermann, Y. Tzvi, editor. | Morrison, Robert G., 1969– , editor. Title: Texts in transit in the medieval Mediterranean / edited by Y. Tzvi Langermann and Robert G. Morrison. Description: University Park, Pennsylvania : The Pennsylvania State University Press, [2016] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: “A collection of essays using historical and philological approaches to study the transit of texts in the Mediterranean basin in the medieval period. Examines the nature of texts themselves and how they travel, and reveals the details behind the transit of texts across cultures, languages, and epochs”— Provided by Publisher. Identifiers: lccn 2016012461 | isbn 9780271071091 (cloth : alk. paper) Subjects: lcsh: Transmission of texts— Mediterranean Region— History— To 1500. | Manuscripts, Medieval— Mediterranean Region. | Civilization, Medieval. Classification: lcc z106.5.m43 t49 2016 | ddc 091 / .0937—dc23 lc record available at https:// lccn .loc .gov /2016012461 Copyright © 2016 The Pennsylvania State University All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Published by The Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park, PA 16802–1003 The Pennsylvania State University Press is a member of the Association of American University Presses. -

AL-KINDI 'Philosopher of the Arabs' Abū Yūsuf Yaʿqūb Ibn Isḥāq Al

AL-KINDI ‘Philosopher of the Arabs’ – from the keyboard of Ghurayb Abū Yūsuf Ya ʿqūb ibn Is ḥāq Al-Kindī , an Arab aristocrat from the tribe of Kindah, was born in Basrah ca. 800 CE and passed away in Baghdad around 870 (or ca. 196–256 AH ). This remarkable polymath promoted the collection of ancient scientific knowledge and its translation into Arabic. Al-Kindi worked most of his life in the capital Baghdad, where he benefitted from the patronage of the powerful ʿAbb āssid caliphs al- Ma’mūn (rg. 813–833), al-Muʿta ṣim (rg. 833–842), and al-Wāthiq (rg. 842–847) who were keenly interested in harmonizing the legacy of Hellenic sciences with Islamic revelation. Caliph al-Ma’mūn had expanded the palace library into the major intellectual institution BAYT al-ḤIKMAH (‘Wisdom House ’) where Arabic translations from Pahlavi, Syriac, Greek and Sanskrit were made by teams of scholars. Al-Kindi worked among them, and he became the tutor of Prince A ḥmad, son of the caliph al-Mu ʿtasim to whom al-Kindi dedicated his famous work On First Philosophy . Al-Kindi was a pioneer in chemistry, physics, psycho–somatic therapeutics, geometry, optics, music theory, as well as philosophy of science. His significant mathematical writings greatly facilitated the diffusion of the Indian numerals into S.W. Asia & N. Africa (today called ‘Arabic numerals’ ). A distinctive feature of his work was the conscious application of mathematics and quantification, and his invention of specific laboratory apparatus to implement experiments. Al-Kindi invented a mathematical scale to quantify the strength of a drug; as well as a system linked to phases of the Moon permitting a doctor to determine in advance the most critical days of a patient’s illness; while he provided the first scientific diagnosis and treatment for epilepsy, and developed psycho-cognitive techniques to combat depression. -

Two Editions of Ibn Al-Haytham's Completion of the Conics

Historia Mathematica 29 (2002), 247–265 doi:10.1006/hmat.2002.2352 Two Editions of Ibn al-Haytham’s Completion of the Conics View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Jan P. Hogendijk provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Mathematics Department, University of Utrecht, P.O. Box 80.010, 3508 TA Utrecht, Netherlands E-mail: [email protected] The lost Book VIII of the Conics of Apollonius of Perga (ca. 200 B.C.) was reconstructed by the Islamic mathematician Ibn al-Haytham (ca. A.D. 965–1041) in his Completion of the Conics. The Arabic text of this reconstruction with English translation and commentary was published as J. P. Hogendijk, Ibn al-Haytham’s Completion of the Conics (New York: Springer-Verlag, 1985). In a new Arabic edition with French translation and commentary (R. Rashed, Les mathematiques´ infinitesimales´ du IXe au XIe siecle.´ Vol. 3., London: Al-Furqan Foundation, 2000), it was claimed that my edition is faulty. In this paper the similarities and differences between the two editions, translations, and commentaries are discussed, with due consideration for readers who do not know Arabic. The facts will speak for themselves. C 2002 Elsevier Science (USA) C 2002 Elsevier Science (USA) C 2002 Elsevier Science (USA) 247 0315-0860/02 $35.00 C 2002 Elsevier Science (USA) All rights reserved. 248 JAN P. HOGENDIJK HMAT 29 AMS subject classifications: 01A20, 01A30. Key Words: Ibn al-Haytham; conic sections; multiple editions; Rashed. 1. INTRODUCTION The Conics of Apollonius of Perga (ca. 200 B.C.) is one of the fundamental texts of ancient Greek geometry. -

History of Mathematics in Mathematics Education. Recent Developments Kathy Clark, Tinne Kjeldsen, Sebastian Schorcht, Constantinos Tzanakis, Xiaoqin Wang

History of mathematics in mathematics education. Recent developments Kathy Clark, Tinne Kjeldsen, Sebastian Schorcht, Constantinos Tzanakis, Xiaoqin Wang To cite this version: Kathy Clark, Tinne Kjeldsen, Sebastian Schorcht, Constantinos Tzanakis, Xiaoqin Wang. History of mathematics in mathematics education. Recent developments. History and Pedagogy of Mathematics, Jul 2016, Montpellier, France. hal-01349230 HAL Id: hal-01349230 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01349230 Submitted on 27 Jul 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. HISTORY OF MATHEMATICS IN MATHEMATICS EDUCATION Recent developments Kathleen CLARK, Tinne Hoff KJELDSEN, Sebastian SCHORCHT, Constantinos TZANAKIS, Xiaoqin WANG School of Teacher Education, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL 32306-4459, USA [email protected] Department of Mathematical Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Denmark [email protected] Justus Liebig University Giessen, Germany [email protected] Department of Education, University of Crete, Rethymnon 74100, Greece [email protected] Department of Mathematics, East China Normal University, China [email protected] ABSTRACT This is a survey on the recent developments (since 2000) concerning research on the relations between History and Pedagogy of Mathematics (the HPM domain). Section 1 explains the rationale of the study and formulates the key issues. -

Maths Week 2021

Maths Week 2021 Survivor Series/Kia Mōrehurehu Monday Level 5 Questions What to do for students 1 You can work with one or two others. Teams can be different each day. 2 Do the tasks and write any working you did, along with your answers, in the spaces provided (or where your teacher says). 3 Your teacher will tell you how you can get the answers to the questions and/or have your work checked. 4 When you have finished each day, your teacher will give you a word or words from a proverb. 5 At the end of the week, put the words together in the right order and you will be able to find the complete proverb! Your teacher may ask you to explain what the proverb means. 6 Good luck. Task 1 – numbers in te reo Māori The following chart gives numbers in te reo Māori. Look at the chart carefully and note the patterns in the way the names are built up from 10 onwards. Work out what each of the numbers in the following calculations is, do each calculation, and write the answer in te reo Māori. Question Answer (a) whitu + toru (b) whā x wa (c) tekau mā waru – rua (d) ono tekau ma whā + rua tekau ma iwa (e) toru tekau ma rua + waru x tekau mā ono Task 2 - Roman numerals The picture shows the Roman Emperor, Julius Caesar, who was born in the year 100 BC. (a) How many years ago was 100 BC? You may have seen places where numbers have been written in Roman numerals. -

On the Use of Coptic Numerals in Egypt in the 16 Th Century

ON THE USE OF COPTIC NUMERALS IN EGYPT IN THE 16 TH CENTURY Mutsuo KAWATOKO* I. Introduction According to the researches, it is assumed that the culture of the early Islamic period in Egypt was very similar to the contemporary Coptic (Qibti)/ Byzantine (Rumi) culture. This is most evident in their language, especially in writing. It was mainly Greek and Coptic which adopted the letters deriving from Greek and Demotic. Thus, it was normal in those days for the official documents to be written in Greek, and, the others written in Coptic.(1) Gold, silver and copper coins were also minted imitating Byzantine Solidus (gold coin) and Follis (copper coin) and Sassanian Drahm (silver coin), and they were sometimes decorated with the representation of the religious legends, such as "Allahu", engraved in a blank space. In spite of such situation, around A. H. 79 (698), Caliph 'Abd al-Malik b. Marwan implemented the coinage reformation to promote Arabisation of coins, and in A. H. 87 (706), 'Abd Allahi b. 'Abd al-Malik, the governor- general of Egypt, pursued Arabisation of official documentation under a decree by Caliph Walid b. 'Abd al-Malik.(2) As a result, the Arabic letters came into the immediate use for the coin inscriptions and gradually for the official documents. However, when the figures were involved, the Greek or the Coptic numerals were used together with the Arabic letters.(3) The Abjad Arabic numerals were also created by assigning the numerical values to the Arabic alphabetic (abjad) letters just like the Greek numerals, but they did not spread very much.(4) It was in the latter half of the 8th century that the Indian numerals, generally regarded as the forerunners of the Arabic numerals, were introduced to the Islamic world. -

By the Persian Mathematician and Engineer Abubakr

1 2 The millennium old hydrogeology textbook “The Extraction of Hidden Waters” by the Persian 3 mathematician and engineer Abubakr Mohammad Karaji (c. 953 – c. 1029) 4 5 Behzad Ataie-Ashtiania,b, Craig T. Simmonsa 6 7 a National Centre for Groundwater Research and Training and College of Science & Engineering, 8 Flinders University, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia 9 b Department of Civil Engineering, Sharif University of Technology, Tehran, Iran, 10 [email protected] (B. Ataie-Ashtiani) 11 [email protected] (C. T. Simmons) 12 13 14 15 Hydrology and Earth System Sciences (HESS) 16 Special issue ‘History of Hydrology’ 17 18 Guest Editors: Okke Batelaan, Keith Beven, Chantal Gascuel-Odoux, Laurent Pfister, and Roberto Ranzi 19 20 1 21 22 Abstract 23 We revisit and shed light on the millennium old hydrogeology textbook “The Extraction of Hidden Waters” by the 24 Persian mathematician and engineer Karaji. Despite the nature of the understanding and conceptualization of the 25 world by the people of that time, ground-breaking ideas and descriptions of hydrological and hydrogeological 26 perceptions such as components of hydrological cycle, groundwater quality and even driving factors for 27 groundwater flow were presented in the book. Although some of these ideas may have been presented elsewhere, 28 to the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that a whole book was focused on different aspects of hydrology 29 and hydrogeology. More importantly, we are impressed that the book is composed in a way that covered all aspects 30 that are related to an engineering project including technical and construction issues, guidelines for maintenance, 31 and final delivery of the project when the development and construction was over. -

The What and Why of Whole Number Arithmetic: Foundational Ideas from History, Language and Societal Changes

Portland State University PDXScholar Mathematics and Statistics Faculty Fariborz Maseeh Department of Mathematics Publications and Presentations and Statistics 3-2018 The What and Why of Whole Number Arithmetic: Foundational Ideas from History, Language and Societal Changes Xu Hu Sun University of Macau Christine Chambris Université de Cergy-Pontoise Judy Sayers Stockholm University Man Keung Siu University of Hong Kong Jason Cooper Weizmann Institute of Science SeeFollow next this page and for additional additional works authors at: https:/ /pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/mth_fac Part of the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Sun X.H. et al. (2018) The What and Why of Whole Number Arithmetic: Foundational Ideas from History, Language and Societal Changes. In: Bartolini Bussi M., Sun X. (eds) Building the Foundation: Whole Numbers in the Primary Grades. New ICMI Study Series. Springer, Cham This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mathematics and Statistics Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Authors Xu Hu Sun, Christine Chambris, Judy Sayers, Man Keung Siu, Jason Cooper, Jean-Luc Dorier, Sarah Inés González de Lora Sued, Eva Thanheiser, Nadia Azrou, Lynn McGarvey, Catherine Houdement, and Lisser Rye Ejersbo This book chapter is available at PDXScholar: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/mth_fac/253 Chapter 5 The What and Why of Whole Number Arithmetic: Foundational Ideas from History, Language and Societal Changes Xu Hua Sun , Christine Chambris Judy Sayers, Man Keung Siu, Jason Cooper , Jean-Luc Dorier , Sarah Inés González de Lora Sued , Eva Thanheiser , Nadia Azrou , Lynn McGarvey , Catherine Houdement , and Lisser Rye Ejersbo 5.1 Introduction Mathematics learning and teaching are deeply embedded in history, language and culture (e.g. -

History of Mathematics

Georgia Department of Education History of Mathematics K-12 Mathematics Introduction The Georgia Mathematics Curriculum focuses on actively engaging the students in the development of mathematical understanding by using manipulatives and a variety of representations, working independently and cooperatively to solve problems, estimating and computing efficiently, and conducting investigations and recording findings. There is a shift towards applying mathematical concepts and skills in the context of authentic problems and for the student to understand concepts rather than merely follow a sequence of procedures. In mathematics classrooms, students will learn to think critically in a mathematical way with an understanding that there are many different ways to a solution and sometimes more than one right answer in applied mathematics. Mathematics is the economy of information. The central idea of all mathematics is to discover how knowing some things well, via reasoning, permit students to know much else—without having to commit the information to memory as a separate fact. It is the reasoned, logical connections that make mathematics coherent. The implementation of the Georgia Standards of Excellence in Mathematics places a greater emphasis on sense making, problem solving, reasoning, representation, connections, and communication. History of Mathematics History of Mathematics is a one-semester elective course option for students who have completed AP Calculus or are taking AP Calculus concurrently. It traces the development of major branches of mathematics throughout history, specifically algebra, geometry, number theory, and methods of proofs, how that development was influenced by the needs of various cultures, and how the mathematics in turn influenced culture. The course extends the numbers and counting, algebra, geometry, and data analysis and probability strands from previous courses, and includes a new history strand. -

Bit, Byte, and Binary

Bit, Byte, and Binary Number of Number of values 2 raised to the power Number of bytes Unit bits 1 2 1 Bit 0 / 1 2 4 2 3 8 3 4 16 4 Nibble Hexadecimal unit 5 32 5 6 64 6 7 128 7 8 256 8 1 Byte One character 9 512 9 10 1024 10 16 65,536 16 2 Number of bytes 2 raised to the power Unit 1 Byte One character 1024 10 KiloByte (Kb) Small text 1,048,576 20 MegaByte (Mb) A book 1,073,741,824 30 GigaByte (Gb) An large encyclopedia 1,099,511,627,776 40 TeraByte bit: Short for binary digit, the smallest unit of information on a machine. John Tukey, a leading statistician and adviser to five presidents first used the term in 1946. A single bit can hold only one of two values: 0 or 1. More meaningful information is obtained by combining consecutive bits into larger units. For example, a byte is composed of 8 consecutive bits. Computers are sometimes classified by the number of bits they can process at one time or by the number of bits they use to represent addresses. These two values are not always the same, which leads to confusion. For example, classifying a computer as a 32-bit machine might mean that its data registers are 32 bits wide or that it uses 32 bits to identify each address in memory. Whereas larger registers make a computer faster, using more bits for addresses enables a machine to support larger programs.