Forging the Climate Movement: Environmental Activism and the Keystone XL Pipeline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Research Report: Nebraska Pilot Test

6.1 Nebraska pilot test Effective Designs for the Administration of Federal Elections Section 6: Research report: Nebraska pilot test June 2007 U.S. Election Assistance Commission 6.2 Nebraska pilot test Nebraska pilot test overview Preparing for an election can be a challenging, complicated process for election offi cials. Production cycles are organized around state-mandated deadlines that often leave narrow windows for successful content development, certifi cation, translations, and election design activities. By keeping election schedules tightly controlled and making uniform voting technology decisions for local jurisdictions, States aspire to error-free elections. Unfortunately, current practices rarely include time or consideration for user-centered design development to address the basic usability needs of voters. As a part of this research effort, a pilot study was conducted using professionally designed voter information materials and optical scan ballots in two Nebraska counties on Election Day, November 7, 2006. A research contractor partnered with Nebraska’s Secretary of State’s Offi ce and their vendor, Elections Systems and Software (ES&S), to prepare redesigned materials for Colfax County and Cedar County (Lancaster County, originally included, opted out of participation). The goal was to gauge overall design success with voters and collaborate with experienced professionals within an actual production cycle with all its variables, time lines, and participants. This case study reports the results of voter feedback on election materials, observations, and interviews from Election Day, and insights from a three-way attempt to utilize best practice design conventions. Data gathered in this study informs the fi nal optical scan ballot and voter information specifi cations in sections 2 and 3 of the best practices documentation. -

May 16, 2008 Primary Election

PR 2008 Official Report Hall County Primary Election Presidential (May 16, 2008) Republican Ticket President of the United States (vote for 1) John McCain 3769 Ron Paul 485 WRITE-IN 101 Total 4355 U.S. Senator (vote for 1) Mike Johanns 3435 Pat Flynn 1025 WRITE-IN 17 Total 4477 U.S. Representative Dist. 3 (vote for 1) Adrian Smith 3612 Jeremiah Ellison 768 WRITE-IN 9 Total 4389 Hall County Public Defender (vote for 1) Gerard Piccolo 3615 (WRITE-IN) 29 Total 3644 Hall County Supervisor Dist. 2 (vote for 1) Jim Eriksen 345 Daniel Purdy 433 WRITE-IN 2 Total 780 Hall County Supervisor Dist. 4 (vote for 1) Pamela E. Lancaster 421 WRITE-IN 10 Total 431 Hall County Supervisor Dist. 6 1 of 6 PR 2008 (vote for 1) Robert M. Humiston, Jr. 165 Gary Quandt 189 WRITE-IN Total 354 Democratic Ticket President of the United States (vote for 1) Hillary Clinton 1558 Mike Gravel 130 Barack Obama 1075 WRITE-IN 34 Total 2797 U.S. Senator (vote for 1) Larry Marvin 49 Scott Kleeb 2245 James Bryan Wilson 44 Tony Raimondo 516 WRITE-IN 5 Total 2859 U.S. Representative Dist. 3 (vote for 1) Jay Stoddard 2043 Paul A. Spatz 565 WRITE-IN 5 Total 2613 Hall County Public Defender (vote for 1) (no declared candidate) (WRITE-IN) 132 Total 132 Hall County Supervisor Dist. 2 (vote for 1) (no declared candidate) WRITE-IN 18 Total 18 Hall County Supervisor Dist. 4 (vote for 1) (no declared candidate) 2 of 6 PR 2008 WRITE-IN 10 Total 10 Hall County Supervisor Dist. -

The Committee on Government, Military and Veterans Affairs Met at 1:30 P.M

Transcript Prepared By the Clerk of the Legislature Transcriber's Office Government, Military and Veterans Affairs Committee January 31, 2008 [LB803 LB991 LB1062 LR225CA] The Committee on Government, Military and Veterans Affairs met at 1:30 p.m. on Thursday, January 31, 2008, in Room 1507 of the State Capitol, Lincoln, Nebraska, for the purpose of conducting a public hearing on LB803, LB991, LB1062, and LR225CA. Senators present: Ray Aguilar, Chairperson; Kent Rogert, Vice Chairperson; Greg Adams; Bill Avery; Mike Friend; Russ Karpisek; Scott Lautenbaugh; and Rich Pahls. Senators absent: None. [ ] SENATOR AGUILAR: Welcome to the Government, Military and Veterans Affairs Committee. I'll start off by introducing the senators that are present. On my far left: Senator Kent Rogert, the Vice Chair of the committee from Tekamah, Nebraska; next to him Christy Abraham our legal counsel; my name is Ray Aguilar, I'm from Grand Island, Chair of the committee; next to me, Sherry Shaffer, committee clerk; Senator Mike Friend from Omaha; Senator Rich Pahls from Omaha; Senator Greg Adams from York; and Senator Bill Avery of Lincoln. Our pages today are Ashley McDonald from Rockville, Nebraska, Courtney Ruwe from Herman, Nebraska. The bills will be taken up in the following order that they are...and also as they are posted on the door: LB803 and LB991 will be heard together, but as you use the sign-in sheets, if you're in favor or against one bill in particular, sign it accordingly; followed by LB1062, LR225CA. The sign-in sheets are at both entrances. Sign in only if you're going to testify and put it in the box up here in front of me. -

2006 Primary Election

2006 Voter Guide State Affi liate to the National & Candidate Survey Right to Life Committee Primary Election - May 9, 2006 Political Action Committee • 404 S. 11th Street • Lincoln, NE 68508 2006 Survey for State Candidates ABORTION-RELATED QUESTIONS embryos created for the express purpose of medical research? 11. Would you support banning the “use” of cloning of human embryos 1. In its 1973 rulings, Roe v. Wade and Doe v. Bolton, the U.S. Supreme either for therapeutic research or for reproductive purposes? Court created a constitutional “right to abortion “which invalidated the 12. Would you oppose efforts to legalize physician-assisted suicide? abortion laws in all 50 states giving us a policy of abortion on demand 13. Do you believe that food and water (nutrition and hydration) along with whereby a woman may obtain an abortion throughout all nine months other basic comfort care, should always be provided to patients, espe- of pregnancy for any reason. Nebraska Right to Life (NRL) believes cially persons with disabilities, the chronically ill and elderly? that unborn children should be protected by law and that abortion is permissible only when the life of the mother is in grave, immediate POLITICAL PARTY QUESTION danger and every effort has been made to save both mother and baby. Under what circumstances, if any, do you believe abortion should be 14. Would you support a pro-life plank in your county, state and national legal? political party platform? 1A. In no case. 1B. Only to prevent the death of the mother. POLITICAL FREE SPEECH QUESTION 1C. In cases of incest and in cases of forcible rape reported to law enforcement authorities. -

Official Results of Nebraska General Election - November 4, 2008 Table of Contents REPORTED PROBLEMS

Page 1 Official Results of Nebraska General Election - November 4, 2008 Table of Contents REPORTED PROBLEMS........................................................................................................................................................ 3 VOTING STATISTICS............................................................................................................................................................. 4 NUMBER OF REGISTERED VOTERS...........................................................................................................................................4 TOTAL VOTING BY LOCATION.................................................................................................................................................6 FEDERAL OFFICES ................................................................................................................................................................ 8 FOR PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES .................................................................................................................................8 FOR PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES BY CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT...............................................................................10 UNITED STATES SENATOR ..................................................................................................................................................... 13 MEMBER OF THE U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES .............................................................................................................15 -

A Moral Call for a National Moratorium on Water, Power and Broadband Shutoffs

To: The Honorable Nancy Pelosi The Honorable Mitch McConnell Speaker Majority Leader U.S. House of Representatives U.S. Senate Washington, D.C. 20515 Washington, D.C. 20510 The Honorable Kevin McCarthy The Honorable Chuck Schumer Minority Leader Democratic Leader U.S. House of Representatives U.S. Senate Washington, D.C. 20515 Washington, D.C. 20510 cc: U.S. Senate Environment and Public Works Committee U.S. Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources U.S. Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation Date: July 30, 2020 A Moral Call for a National Moratorium on Water, Power and Broadband Shutoffs Dear Senate Majority Leader McConnell, Minority Leader Schumer, Speaker Pelosi, Minority Leader McCarthy, Chairman Barrasso, and Ranking Member Carper, Chairwoman Murkowski, Ranking Member Manchin, Chairman Wicker, and Ranking Member Cantwell: On behalf of our congregants, members and supporters nationwide, we, the undersigned 537 faith leaders and organizations urge Congress to take decisive, moral action and implement a nationwide moratorium on the shut-offs of electricity, water, broadband, and all other essential utility services for all households, places of worship, and other non-profit community centers as part of the next COVID-19 rescue package. As faith leaders in the Christian, Muslim, Jewish, Buddhist, Baha’i, and other religious traditions, we call on you to come to the aid of struggling families and houses of worship across the country--and ensure that we all have access to water, power, and broadband during the ongoing coronavirus pandemic. Nearly 80% of the American population self identifies as being grounded in a faith ideology. -

Billionaire's Club

United States Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works Minority Staff Report The Chain of Environmental Command: How a Club of Billionaires and Their Foundations Control the Environmental Movement and Obama’s EPA July 30, 2014 Contact: Luke Bolar — [email protected] (202) 224-6176 Cheyenne Steel — [email protected] (202) 224-6176 U.S. Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works (Minority) EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In his 2010 State of the Union Address, President Obama famously chided the Supreme Court for its recent campaign finance decision by proclaiming, “With all due deference to the separation of powers, the Supreme Court reversed a century of law to open the floodgates for special interests – including foreign corporations – to spend without limit in our elections."1 In another speech he further lamented, “There aren’t a lot of functioning democracies around the world that work this way where you can basically have millionaires and billionaires bankrolling whoever they want, however they want, in some cases undisclosed. What it means is ordinary Americans are shut out of the process.”2 These statements are remarkable for their blatant hypocrisy and obfuscation of the fact that the President and his cadre of wealthy liberal allies and donors embrace the very tactics he publically scorned. In reality, an elite group of left wing millionaires and billionaires, which this report refers to as the “Billionaire’s Club,” who directs and controls the far-left environmental movement, which in turn controls major policy decisions and lobbies on behalf of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Even more unsettling, a dominant organization in this movement is Sea Change Foundation, a private California foundation, which relies on funding from a foreign company with undisclosed donors. -

Ethanol: Salvation Or Damnation?

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Journalism & Mass Communications: Student Journalism and Mass Communications, College Media of Fall 2008 Ethanol: Salvation or Damnation? Mimi Abebe University of Nebraska-Lincoln Melissa Drozda University of Nebraska - Lincoln Cassie Fleming University of Nebraska - Lincoln Lucas Jameson University of Nebraska - Lincoln Aaron E. Price University of Nebraska - Lincoln See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/journalismstudent Part of the Journalism Studies Commons Abebe, Mimi; Drozda, Melissa; Fleming, Cassie; Jameson, Lucas; Price, Aaron E.; Veik, Kate; Koiwai, Kosuke; Hauter, Alex; Costello, Penny; Jacobs, Stephanie; Soukup, Amanda; Anderson, Emily; Vander Weil, Michaela; Smith, Shannon; Koperski, Scott; Wittstruck, Mallory; Johnsen, Carolyn; Starita, Joe; Stoner, Perry; Farrell, Michael; and Hahn, Marilyn, "Ethanol: Salvation or Damnation?" (2008). Journalism & Mass Communications: Student Media. 3. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/journalismstudent/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journalism and Mass Communications, College of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journalism & Mass Communications: Student Media by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Authors Mimi Abebe, Melissa Drozda, Cassie Fleming, Lucas Jameson, Aaron E. Price, Kate Veik, Kosuke Koiwai, Alex Hauter, -

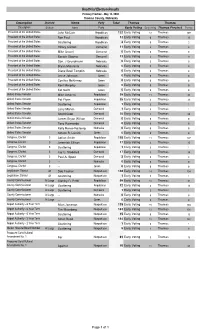

2008 Primary Election Results

Unofficial Election Results Primary Election - May 13, 2008 Thomas County, Nebraska Description District# Name Party Total Thomas Thomas Description District# Name Party Early Voting Early Voting Thomas Precinct Thomas President of the United States John McCain Republican 122 Early Voting 13 Thomas 109 President of the United States Ron Paul Republican 12 Early Voting 0 Thomas 12 President of the United States Scattering Republican 2 Early Voting 0 Thomas 2 President of the United States Hillary Clinton Democrat 11 Early Voting 3 Thomas 8 President of the United States Mike Gravel Democrat 0 Early Voting 0 Thomas 0 President of the United States Barack Obama Democrat 13 Early Voting 2 Thomas 11 President of the United States Don. J Grundmann Nebraska 0 Early Voting 0 Thomas 0 President of the United States Bryan Malatesta Nebraska 0 Early Voting 0 Thomas 0 President of the United States Diane Beall Templin Nebraska 0 Early Voting 0 Thomas 0 President of the United States Jesse Johnson Green 0 Early Voting 0 Thomas 0 President of the United States Cynthia McKinney Green 0 Early Voting 0 Thomas 0 President of the United States Kent Mesplay Green 0 Early Voting 0 Thomas 0 President of the United States Kat Swift Green 0 Early Voting 0 Thomas 0 United States Senator Mike Johanns Republican 99 Early Voting 11 Thomas 88 United States Senator Pat Flynn Republican 35 Early Voting 2 Thomas 33 United States Senator Scattering Republican 1 Early Voting 0 Thomas 1 United States Senator Larry Marvin Democrat 1 Early Voting 0 Thomas 1 United States Senator Scott Kleeb Democrat 25 Early Voting 5 Thomas 20 United States Senator James Bryan Wilson Democrat 0 Early Voting 0 Thomas 0 United States Senator Tony Raimondo Democrat 0 Early Voting 0 Thomas 0 United States Senator Kelly Renee Rosberg Nebraska 0 Early Voting 0 Thomas 0 United States Senator Steven R. -

Official Results School Bond Election Official Results for Early Voters General Election 2008 Results

OFFICIAL RESULTS SCHOOL BOND ELECTION OFFICIAL School Bond Election Results Phelps County School District 44 Tuesday, September 15, 2009 FOR said bonds and tax- 794 AGAINST said bonds and tax- 1650 OFFICIAL RESULTS FOR EARLY VOTERS OFFICIAL EARLY VOTING RESULTS School Bond Election Results Phelps County School District 44 Tuesday, September 15, 2009 FOR said bonds and tax 91 AGAINST said bonds and tax 238 GENERAL ELECTION 2008 RESULTS GENERAL ELECTION 2008 RESULTS OFFICAL RESULTS General Election Results Phelps County General Election 4-Nov-08 Precincts Counted (of 14) 14 Registered Voters 6468 Ballots Counted 4539 FOR PRESIDENT & VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES John McCain/Sara Palin 3360 Barack Obama/Joseph Biden 1050 Chuck Baldwin/Darrel Castle 14 Cynthia McKinney/Rosa Clemente 3 Bob Barr/Wayne Root 11 Ralph Nader/Matt Gonzalez 27 FOR UNITED STATES SENATOR Mike Johanns 3058 Scott Kleeb 1392 Kelly Renee Rosberg 33 Steven R. Larrick 11 REPRESENTATIVE IN CONGRESS DISTRICT 3 Adrian smith 3657 Jay Stoddard 765 COUNTY SUPERVISOR DIST-2 Russell A. Cruise 534 COUNTY SUPERVISOR DIST-4 Theresa Puls 590 COUNTY SUPERVISOR DIST-6 Harold Raburn 652 JUDGE OF WORKERS COMP COURT LAUREEN K. VAN NORMAN Yes 2786 No 762 JUDGE OF WORKERS COMP COURT MICHAEL K. HIGH Yes 2790 No 726 JUDGE OF DISTRICT COURT TERRI HARDER Yes 2869 No 716 CENTRAL COMMUNITY COLLEGE DIST-2 Merikay Gengenbach 3280 CENTRAL COMMUNITY COLLEGE AT LARGE Sam Cowan 1646 Homer Pierce 1246 CENTRAL NEBRASKA PPD PHELPS Roger Olson 3623 TRI BASIN NRD SUB DIST 1 Larry Reynolds 275 TRI BASIN NRD SUB DIST 2 Phyllis Johnson 1153 TRI BASIN NRD SUB DIST 3 Ray Winz 1102 TRI BASIN NRD SUB DIST 4 Todd Garrelts 961 ESU 10 DIST 6 Robert Reed 6 ESU 10 DIST 7 Ronal Tuttle 32 ESU 11 DIST 2 Maryilyn Winkler 956 ESU 11 DIST 4 Susan Perry 1016 TWIN VALLEY PPD SUBDIV 1 6 YR TERM Bruce Lans 93 TWIN VALLEY PPD SUBDIV 1 2 YR TERM David Black 96 DAWSON PPD Robert Stubblefield 4 BOARD OF EDUCATION-HOLDREGE Vote for 3 Teresa J. -

2008 General Election Results

OFFICIAL 2008 GENERAL ELECTION RESULTS FOR FILLMORE COUNTY 12 OF 12 PRECINCTS (Updated 11/06/2008) Votes Votes President of the United States Little Blue NRD Board, Subdistrict #7 John McCain (Republican) 1913 Tim Pohlmann 262 Barack Obama (Democrat) 962 Chuck Baldwin (Nebraska) 18 Little Blue NRD Board, Subdistrict #8 Cynthia McKinney (Green) 5 James Cunningham 251 Bob Barr (Libertarian) 7 Ralph Nader (By Petition) 27 Upper Big Blue NRD Board, Subdistrict #1 Roger Houdersheldt 1663 United States Senator Mike Johanns (Republican) 1610 Upper Big Blue NRD Board, Subdistrict #2 Scott Kleeb (Democrat) 1315 Yvonne C. Austin 1660 Kelly Renee Rosberg (Nebraska) 30 Steven R. Larrick (Green) 8 Upper Big Blue NRD Board, Subdistrict #3 Douglas Bruns 1671 Representative in Congress, District 3 Adrian Smith (Republican) 2175 Upper Big Blue NRD Board, Subdistrict #5 Jay C. Stoddard (Democrat) 637 Merlin Volkmer 1839 County Supervisor, District #2 Upper Big Blue NRD Board, Subdistrict #6 Albert Simacek (Republican) 337 William Kuehner 393 John Miller 1364 County Supervisor, District #4 Larry L. Cerny (Republican) 410 Upper Big Blue NRD Board, Subdistrict #6 Gary Eberle 1634 County Supervisor, District #6 Ray Capek (Democrat) 340 Upper Big Blue NRD Board, Subdistrict #8 Steve Buller 1615 Retain Judge Laureen K. Van Norman Yes 1662 ESU 5, District 2 No 554 Debra K. Meyer 51 Retain Judge Michael K. High ESU 6, District 2 Yes 1593 Dale Kahla 1 No 579 ESU 9, District 4 Retain Judge Daniel E. Bryan, Jr. Sam Townsend 68 Yes 2117 No 417 Fillmore County Weed Board Gary Richards 1830 Retain Judge Paul W. -

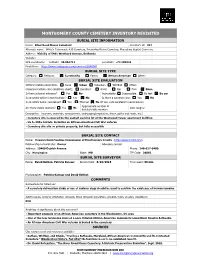

White's Tabernacle No. 39

MONTGOMERY COUNTY CEMETERY INVENTORY REVISITED BURIAL SITE INFORMATION Name: River Road Moses Cemetery Inventory ID: 327 Alternate name: White's Tabernacle #39 Cemetery, Friendship Moses Cemetery, Macedonia Baptist Cemetery Address: Vicinity of 5401 Westbard Avenue, Bethesda Website: GPS coordinates: Latitude: 38.964711 Longitude: -77.105944 FindaGrave: https://www.findagrave.com/cemetery/2648340 BURIAL SITE TYPE Category: Religious Community Family African American Other: BURIAL SITE EVALUATION Setting/location description: Rural Urban Suburban Wooded Other: General condition (See conditions sheet): Excellent Good Fair Poor None Is there a formal entrance? Yes No Accessibility: Inaccessible By foot By car Is cemetery active (recent burials)? Yes No Is there a cemetery sign: Yes No Is cemetery being maintained? Yes Minimal No (If yes, note caretaker’s name below) Approximate number of Are there visible markers? Yes o N Date ranges: burials/visible markers: Description: (markers, materials, arrangement, landscaping/vegetation, fence, paths and roads, etc.) • Cemetery site is covered by the asphalt parking lot of the Westwood Tower apartment building • Up to 200+ burials, including an African-American Civil War veteran • Cemetery site sits on private property, but fully accessible BURIAL SITE CONTACT Name: Housing Opportunities Commission of Montgomery County (http://www.hocmc.org/) Relationship to burial site: Owner Advocacy contact: Address: 10400 Detrick Avenue Phone: 240-627-9400 City: Kensington State: MD ZIP Code: 20895 BURIAL SITE SURVEYOR Name: David Kathan, Patricia Kolesar Survey Date: 8/19/2018 Time spent: 30 min Photographer: Patricia Kolesar and David Kathan COMMENTS Suggestions for follow-up: • A cemetery delineation study or use of cadaver dogs should be used to confirm the existence of human remains.