Forum on Religion and Ecology at Yale Religion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philosophy, Science, Antiscience the Institute of Philosophy Summer School 2020 Zagreb, 15-17 June 2020

Philosophy, Science, Antiscience The Institute of Philosophy Summer School 2020 Zagreb, 15-17 June 2020 MONDAY 9.30-10.00 Registration 10.00-13.00 Course 1 Dr. Luka Boršić (Institute of Philosophy, Zagreb) Anti-Aristotelianism and the Emergence of Modern Science 13.00-16.00 Break 16.00-19.00 Course 2 Professor Robert J. Hankinson (University of Texas at Austin) Physics, Mathematics, and Explanation in Aristotle TUESDAY 10.00-13.00 Course 3 Dr. Ivana Skuhala Karasman (Institute of Philosophy, Zagreb) Astrology: From Science to Pseudoscience 13.00-15.00 Break 15.00-18.00 Course 4 Professor Jure Zovko (Institute of Philosophy, Zagreb / University of Zadar) Does Relativism Threaten the Sciences? WEDNESDAY 10.00-13.00 Course 5 Dr. Marija Brajdić Vuković (Institute of Social Research, Zagreb) What is an Expert? Scientific and Public Controversies 13.00-15.00 Break 15.00-18.00 Course 6 Professor Luca Malatesti (University of Rijeka) Science in the Courtroom. Some Conceptual and Methodological Issues in Transferring Neuropsychological Science in the Insanity Defence 18:00-18:30 Break 1 18.30-20.00 Closing Lecture Professor Darko Polšek (Department of Anthropology, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Zagreb) Science: Good, Bad and Bogus (New Challenges!) 2 COURSE 1 Anti-Aristotelianism and the Emergence of Modern Science INSTRUCTOR Dr. Luka Boršić (Institute of Philosophy, Zagreb) ABSTRACT We are going to inquire into the changes of paradigm that happened notably in the 16th century and which prepared the ground for the emergence of modern science. In more detail we are going to explore the texts of three Renaissance philosophers: Mario Nizolio (De veris principiis), Frane Petrić (Francesco Patrizi, Discussiones peripateticae) and Jacopo Mazzoni (In universam Platonis et Aristotelis philosophiam praeludia). -

Demystifying the Placebo Effect

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2018 Demystifying the Placebo Effect Phoebe Friesen The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2775 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] DEMYSTIFYING THE PLACEBO EFFECT by PHOEBE FRIESEN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Philosophy in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2018 © 2018 PHOEBE FRIESEN All Rights Reserved ii Demystifying the Placebo Effect by Phoebe Friesen This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Philosophy in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ___________ ____________________________________ Date [Peter Godfrey-Smith] Chair of Examining Committee ___________ ____________________________________ Date [Nickolas Pappas ] Executive Office Supervisory Committee: Peter Godfrey-Smith Jesse Prinz John Greenwood THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Demystifying the Placebo Effect by Phoebe Friesen Advisor: Peter Godfrey-Smith This dissertation offers a philosophical analysis of the placebo effect. After offering an overview of recent evidence concerning the phenomenon, I consider several prominent accounts of the placebo effect that have been put forward and argue that none of them are able to adequately account for the diverse instantiations of the phenomenon. I then offer a novel account, which suggests that we ought to think of the placebo effect as encompassing three distinct responses: conditioned placebo responses, cognitive placebo responses, and network placebo responses. -

Flint Fights Back, Environmental Justice And

Thank you for your purchase of Flint Fights Back. We bet you can’t wait to get reading! By purchasing this book through The MIT Press, you are given special privileges that you don’t typically get through in-device purchases. For instance, we don’t lock you down to any one device, so if you want to read it on another device you own, please feel free to do so! This book belongs to: [email protected] With that being said, this book is yours to read and it’s registered to you alone — see how we’ve embedded your email address to it? This message serves as a reminder that transferring digital files such as this book to third parties is prohibited by international copyright law. We hope you enjoy your new book! Flint Fights Back Urban and Industrial Environments Series editor: Robert Gottlieb, Henry R. Luce Professor of Urban and Environmental Policy, Occidental College For a complete list of books published in this series, please see the back of the book. Flint Fights Back Environmental Justice and Democracy in the Flint Water Crisis Benjamin J. Pauli The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England © 2019 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. This book was set in Stone Serif by Westchester Publishing Services. Printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Pauli, Benjamin J., author. -

A Moral Call for a National Moratorium on Water, Power and Broadband Shutoffs

To: The Honorable Nancy Pelosi The Honorable Mitch McConnell Speaker Majority Leader U.S. House of Representatives U.S. Senate Washington, D.C. 20515 Washington, D.C. 20510 The Honorable Kevin McCarthy The Honorable Chuck Schumer Minority Leader Democratic Leader U.S. House of Representatives U.S. Senate Washington, D.C. 20515 Washington, D.C. 20510 cc: U.S. Senate Environment and Public Works Committee U.S. Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources U.S. Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation Date: July 30, 2020 A Moral Call for a National Moratorium on Water, Power and Broadband Shutoffs Dear Senate Majority Leader McConnell, Minority Leader Schumer, Speaker Pelosi, Minority Leader McCarthy, Chairman Barrasso, and Ranking Member Carper, Chairwoman Murkowski, Ranking Member Manchin, Chairman Wicker, and Ranking Member Cantwell: On behalf of our congregants, members and supporters nationwide, we, the undersigned 537 faith leaders and organizations urge Congress to take decisive, moral action and implement a nationwide moratorium on the shut-offs of electricity, water, broadband, and all other essential utility services for all households, places of worship, and other non-profit community centers as part of the next COVID-19 rescue package. As faith leaders in the Christian, Muslim, Jewish, Buddhist, Baha’i, and other religious traditions, we call on you to come to the aid of struggling families and houses of worship across the country--and ensure that we all have access to water, power, and broadband during the ongoing coronavirus pandemic. Nearly 80% of the American population self identifies as being grounded in a faith ideology. -

Download PDF 650.02 KB

Rea, The Medieval Slut Page 1 of 163 The Medieval Slut Sexual Identities of Medieval Women in the Patriarchal Narratives of the Decameron and Canterbury Tales Rosalynd Rea Advised by Professor Cord J. Whitaker of the English Department Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Prerequisite for Honors in Medieval & Renaissance Studies May 2019 Rea, The Medieval Slut Page 2 of 163 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Chapter One: The Introductory Slut............................................................................................................... 5 Chapter Two: The Courtly Slut ..................................................................................................................... 25 Chapter Three: The Adulterous Slut ............................................................................................................. 69 Chapter Four: The Professional Slut .......................................................................................................... 106 Chapter Five: The Conclusory Slut or The Modern Medieval Slut ....................................................... 140 Works Cited ................................................................................................................................................... 159 Rea, The Medieval Slut Page 3 of 163 Acknowledgements I would like to start by thanking Professor Cord Whitaker, without whom -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 104 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 104 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 142 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, MAY 29, 1996 No. 76 Senate The Senate was not in session today. Its next meeting will be held on Monday, June 3, 1996, at 1:30 p.m. House of Representatives WEDNESDAY, MAY 29, 1996 The House met at 2 p.m. and was THE JOURNAL COMMUNICATION FROM THE called to order by the Speaker pro tem- The SPEAKER pro tempore. The CLERK OF THE HOUSE pore [Ms. GREENE of Utah]. Chair has examined the Journal of the The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- f last day's proceedings and announces fore the House the following commu- to the House his approval thereof. nication from the Clerk of the House of Pursuant to clause 1, rule I, the Jour- Representatives: DESIGNATION OF THE SPEAKER nal stand as approved. PRO TEMPORE U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, Mr. CHABOT. Madam Speaker, pur- Washington, DC, May 28, 1996. The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- suant to clause 1, rule I, I demand a Hon. NEWT GINGRICH, fore the House the following commu- vote on agreeing to the Speaker's ap- The Speaker, U.S. House of Representatives, nication from the Speaker: proval of the Journal. Washington, DC. DEAR MR. SPEAKER: Pursuant to the per- WASHINGTON, DC, The SPEAKER pro tempore. The May 29, 1996. mission granted in Clause 5 of Rule III of the question is on the Chair's approval of Rules of the U.S. -

Social Thinking®: Science, Pseudoscience, Or Antiscience?

Behav Analysis Practice DOI 10.1007/s40617-016-0108-1 DISCUSSION AND REVIEW PAPER Social Thinking®: Science, Pseudoscience, or Antiscience? Justin B. Leaf1 & Alyne Kassardjian1 & Misty L. Oppenheim-Leaf2 & Joseph H. Cihon1 & Mitchell Taubman1 & Ronald Leaf1 & John McEachin1 # Association for Behavior Analysis International 2016 Abstract Today, there are several interventions that can be has been utilized by behaviorists and non-behaviorists. This implemented with individuals diagnosed with autism spec- commentary will outline Social Thinking® and provide evi- trum disorder. Most of these interventions have limited to no dence that the procedure, at the current time, qualifies as a empirical evidence demonstrating their effectiveness, yet they pseudoscience and, therefore, should not be implemented with are widely implemented in home, school, university, and com- individuals diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, espe- munity settings. In 1996, Green wrote a chapter in which she cially given the availability of alternatives which clearly meet outlined three levels of science: evidence science, pseudosci- the standard of evidence science. ence, and antiscience; professionals were encouraged to im- plement and recommend only those procedures that would be Keywords Applied behavior analysis . Evidence based . considered evidence science. Today, an intervention that is Social behavior . Social thinking . Autism commonly implemented with individuals diagnosed with au- tism spectrum disorder is Social Thinking®. This intervention In 1996, Green wrote a seminal chapter entitled, Evaluating Claims about Treatments for Autism.Inthischapter,Green * Justin B. Leaf described three levels of science (i.e., science, pseudoscience, [email protected] and antiscience) which can be utilized as a guide to evaluate treatments for individuals diagnosed with autism spectrum Alyne Kassardjian disorders (ASD). -

Destruction and Human Remains

Destruction and human remains HUMAN REMAINS AND VIOLENCE Destruction and human remains Destruction and Destruction and human remains investigates a crucial question frequently neglected in academic debate in the fields of mass violence and human remains genocide studies: what is done to the bodies of the victims after they are killed? In the context of mass violence, death does not constitute Disposal and concealment in the end of the executors’ work. Their victims’ remains are often treated genocide and mass violence and manipulated in very specific ways, amounting in some cases to true social engineering with often remarkable ingenuity. To address these seldom-documented phenomena, this volume includes chapters based Edited by ÉLISABETH ANSTETT on extensive primary and archival research to explore why, how and by whom these acts have been committed through recent history. and JEAN-MARC DREYFUS The book opens this line of enquiry by investigating the ideological, technical and practical motivations for the varying practices pursued by the perpetrator, examining a diverse range of historical events from throughout the twentieth century and across the globe. These nine original chapters explore this demolition of the body through the use of often systemic, bureaucratic and industrial processes, whether by disposal, concealment, exhibition or complete bodily annihilation, to display the intentions and socio-political frameworks of governments, perpetrators and bystanders. A NST Never before has a single publication brought together the extensive amount of work devoted to the human body on the one hand and to E mass violence on the other, and until now the question of the body in TTand the context of mass violence has remained a largely unexplored area. -

Inherited Memory: a Comparison of How World War II

Inherited Memory A Qualitative Study of How World War II Influences the Japanese Postwar Generation Submitted in fulfillment of the final project requirement for the Diploma of Process Work from the Process Work Center of Portland Graduate School by Ayako Fujisaki, M.A. November, 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS AKNOW LEDGEMENTS ……………..…………………………………………………………….. i ABSTRACT ………………………………………………………………………………………… iii I INTRO DUCTIO N………………………………..………………………………………………1 Research Purpose ………………………………………………......…………………… 5 Method ……………………………………………………………..……………………… 8 Introduction to Process W ork …………………………………………………………... 9 W orldwork ………………………………………………………...………………….. 10 Deep Dem ocracy……………………………………………...…………………… 11 Fields ………………………………………………………………………………….. 12 Role/Tim espirits ……………………………………………………………………… 12 G hosts ………………………………………………………………………...………. 13 Hot Spots …………………………………………………………………………….. 14 Overview of This Thesis ………………………………………………………………… 14 II METHODOLOGY ……………………………………………………………………………. 19 Methodology ……………………………………………………...…………………….. 19 Focus G roups ………………………………………………………………………... 21 Evaluation of This Study ……………………………………………………………. 24 Placem ent of Literature Review …………………………………………………. 26 Current Study …………………………………………………………………………….. 27 Participants ………………………………………………………………………….. 27 Q uestions …………………………………………………………………………….. 29 Analysis ………………………………………………………………………….……. 30 Ethical Considerations ……………………………………………………..………. 31 Issue of Translation ……………………………………………………………..…… 33 Sum m ary ……………………………………………………………………………..…… 34 III SUBJECTIVITY OF THE RESEACHER -

313 3D in Your Face 44 Magnum 5 X a Cosmic Trail A

NORMALPROGRAMM, IMPORTE, usw. Richtung Within Temptation mit einem guten Schuß Sentenced ALLOY CZAR ANGEL SWORD ACCUSER Awaken the metal king CD 15,50 Rebels beyond the pale CD 15,50 Dependent domination CD 15,50 Moderater NWoBHM Sound zwischen ANGRA BITCHES SIN, SARACEN, DEMON, Secret garden CD 15,50 Diabolic CD 15,50 SATANIC RITES gelegen. The forlorn divide CD 15,50 ALLTHENIKO ANGRA (ANDRE MATOS) Time to be free CD 29,00 ACID Back in 2066 CD 15,50 Japan imp. Acid CD 18,00 Devasterpiece CD 15,50 ANGUISH FORCE Engine beast CD 18,00 Millennium re-burn CD 15,50 2: City of ice CD 12,00 ACRIDITY ALMANAC 3: Invincibile imperium Italicum CD 15,50 For freedom I cry & bonustracks CD 17,00 Tsar - digibook CD & DVD 18,50 Cry, Gaia cry CD 12,00 ACTROID ALMORA Defenders united MCD 8,00 Crystallized act CD 29,00 1945 CD 15,50 Japan imp. RRR (1998-2002) CD 15,50 Kalihora´s song CD 15,50 Sea eternally infested CD 12,00 ABSOLVA - Sid by side CD 15,50 ADRAMELCH Kiyamet senfonisi CD 15,50 Broken history CD 15,50 ANIMETAL USA Shehrazad CD 15,50 Lights from oblivion CD 15,50 W - new album 2012 CD 30,00 313 ALTAR OF OBLIVION Japan imp. Opus CD 15,50 Three thirteen CD 17,00 Salvation CD 12,00 ANNIHILATED ADRENALINE KINGS 3D IN YOUR FACE ALTERED STATE Scorched earth policy CD 15,50 Same CD 15,50 Faster and faster CD 15,50 Winter warlock CD 15,50 ANNIHILATOR ADRENICIDE Eine tolle, packende Mischung aus AMARAN Alice in hell CD 12,00 PREMONITION (Florida) ILIUM, HAN- War begs no mercy CD 15,50 KER und neueren JAG PANZER. -

REGLEMENT Jeu « Sony Days 2018 »

REGLEMENT Jeu « Sony Days 2018 » Article 1. - Sociétés Organisatrices Sony Interactive Entertainment ® France SAS, au capital de 40 000 €, enregistrée au RCS de Nanterre sous le N° 399 930 593, située 92 avenue de Wagram, 75017 Paris ; Sony Mobile Communications, enregistrée au RCS de Nanterre sous le n°439 961 905, située 49-51 quai de Dion Bouton 92800 Puteaux ; Sony Pictures Home Entertainment France SNC, au capital de 107 500 €, enregistrée au RCS de Nanterre en date du 02/03/1987 sous le N° 324 834 266, située 25 quai Gallieni, 92150 Suresnes ; Sony Music Entertainment, France, SAS au capital de 2.524.720 €, enregistrée au RCS de Paris sous le n°542 055 603, située 52/54, rue de Châteaudun, 75009 Paris ; SONY France , succursale de Sony Europe Limited, 49-51 quai de Dion Bouton 92800 Puteaux , RCS Nanterre 390 711 323 (ci-après les « Sociétés Organisatrices ») ; organise un jeu avec obligation d’achat uniquement dans les magasins Fnac et Darty ainsi que sur le sites www.fnac.com et www.darty.com (ci-après le « Jeu ») par le biais d’instants gagnants ouverts du 02/04/2018 10h au 15/04/2018 23h59 inclus ouvert aux personnes physiques majeures (sous réserve des dispositions indiquées à l’article 2) résidant en France Métropolitaine (Corse et DROM-COM exclus). Article 2. - Participation Ce jeu est ouvert à toute personne physique majeure, résidant en France métropolitaine (Corse et DROM-COM exclus), à l'exception des mineurs, du personnel de la société organisatrice et des membres des sociétés partenaires de l'opération ainsi que de leur famille en ligne directe. -

White's Tabernacle No. 39

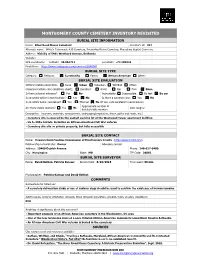

MONTGOMERY COUNTY CEMETERY INVENTORY REVISITED BURIAL SITE INFORMATION Name: River Road Moses Cemetery Inventory ID: 327 Alternate name: White's Tabernacle #39 Cemetery, Friendship Moses Cemetery, Macedonia Baptist Cemetery Address: Vicinity of 5401 Westbard Avenue, Bethesda Website: GPS coordinates: Latitude: 38.964711 Longitude: -77.105944 FindaGrave: https://www.findagrave.com/cemetery/2648340 BURIAL SITE TYPE Category: Religious Community Family African American Other: BURIAL SITE EVALUATION Setting/location description: Rural Urban Suburban Wooded Other: General condition (See conditions sheet): Excellent Good Fair Poor None Is there a formal entrance? Yes No Accessibility: Inaccessible By foot By car Is cemetery active (recent burials)? Yes No Is there a cemetery sign: Yes No Is cemetery being maintained? Yes Minimal No (If yes, note caretaker’s name below) Approximate number of Are there visible markers? Yes o N Date ranges: burials/visible markers: Description: (markers, materials, arrangement, landscaping/vegetation, fence, paths and roads, etc.) • Cemetery site is covered by the asphalt parking lot of the Westwood Tower apartment building • Up to 200+ burials, including an African-American Civil War veteran • Cemetery site sits on private property, but fully accessible BURIAL SITE CONTACT Name: Housing Opportunities Commission of Montgomery County (http://www.hocmc.org/) Relationship to burial site: Owner Advocacy contact: Address: 10400 Detrick Avenue Phone: 240-627-9400 City: Kensington State: MD ZIP Code: 20895 BURIAL SITE SURVEYOR Name: David Kathan, Patricia Kolesar Survey Date: 8/19/2018 Time spent: 30 min Photographer: Patricia Kolesar and David Kathan COMMENTS Suggestions for follow-up: • A cemetery delineation study or use of cadaver dogs should be used to confirm the existence of human remains.