Flint Fights Back, Environmental Justice And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2008 and 2013 Flint River Watershed Biosurvey Monitoring Report

MI/DEQ/WRD-17/009 MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY WATER RESOURCES DIVISION APRIL 2017 STAFF REPORT A BIOLOGICAL SURVEY OF THE FLINT RIVER AND SELECTED TRIBUTARIES IN GENESEE, LAPEER, OAKLAND, SANILAC, SAGINAW, SHIAWASSEE, AND TUSCOLA COUNTIES JUNE-SEPTEMBER 2008 AND 2013 Qualitative biological sampling of the Flint River watershed was conducted by staff of the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ), Surface Water Assessment Section (SWAS), from June-September of both 2008 and 2013 as part of a five-year watershed monitoring cycle. The Flint River watershed is a vast watershed that falls within two ecoregions: the Southern Michigan Northern Indiana Till Plain and Huron and Lake Erie Till Plain ecoregions (Omernik and Gallant, 1988). Land use in the Flint River watershed is predominantly agriculture and forested with portions also being urban. The Flint River is a major tributary to the Saginaw River/Bay ecosystem. OBJECTIVES These biological surveys were conducted to: • Assess the current status condition of individual waters to determine attainment of Michigan Water Quality Standards (WQS). • Evaluate potential impacts from National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES)-regulated sources to water quality in the watersheds. • Identify potential nonpoint sources (NPS) of water quality impairment. • Satisfy monitoring request submitted by internal and external customers. The locations of the surveyed biological stations are illustrated in Figures 1a (2008) and 1b (2013) and Tables 1a (2008) and 1b (2013). For the 2008 data, detailed macroinvertebrate, fish, and habitat sampling results are provided in Tables 2a and 2b, 3a and 3b, and 4, respectively. Water (14 locations) and sediment (2 locations) chemistry samples were collected during the 2008 watershed assessment; locations and results can be found in Tables 5 and 6. -

The Flint Water Crisis, KWA and Strategic-Structural Racism

The Flint Water Crisis, KWA and Strategic-Structural Racism By Peter J. Hammer Professor of Law and Director Damon J. Keith Center for Civil Rights Wayne State University Law School Written Testimony Submitted to the Michigan Civil Rights Commission Hearings on the Flint Water Crisis July 18, 2016 i Table of Contents I Flint, Municipal Distress, Emergency Management and Strategic- Structural Racism ………………………………………………………………... 1 A. What is structural and strategic racism? ..................................................1 B. Knowledge, power, emergency management and race………………….3 C. Flint from a perspective of structural inequality ………………………. 5 D. Municipal distress as evidence of a history of structural racism ………7 E. Emergency management and structural racism………………………... 9 II. KWA, DEQ, Treasury, Emergency Managers and Strategic Racism………… 11 A. The decision to approve Flint’s participation in KWA………………… 13 B Flint’s financing of KWA and the use of the Flint River for drinking water………………………………………………………………………. 22 1. The decision to use the Flint River………………………………. 22 2. Flint’s financing of the $85 million for KWA pipeline construction ..……………………………………………………. 27 III. The Perfect Storm of Strategic and Structural Racism: Conflicts, Complicity, Indifference and the Lack of an Appropriate Political Response……………... 35 A. Flint, Emergency Management and Structural Racism……………….. 35 B. Strategic racism and the failure to respond to the Flint water crisis…. 38 VI Conclusion ……………………………………………………………………….. 45 Appendix: Peter J. Hammer, The Flint Water Crisis: History, Housing and Spatial-Structural Racism, Testimony before Michigan Civil Rights Commission Hearing on Flint Water Crisis (July 14, 2016) ……………………… 46 ii The Flint Water Crisis, KWA and Strategic-Structural Racism By Peter J. Hammer1 Flint is a complicated story where race plays out on multiple dimensions. -

Making It LOUD

Making it LOUD 2011 Annual Report WWW.USFIRST.ORG1 For over 20 years, FIRST® Founder Dean Kamen and everyone associated with FIRST have been on a mission to spread President Barack Obama, along with White House Technology Officer Aneesh Chopra, continued to feature FIRST teams as perfect examples of the president’s national White the word about the many educational, societal, economical, and House Science Fair initiative promoting STEM (science, technology, engineering, and Dean Kamen will.i.am planetary benefits of getting youth and adults alike involved in theFIRST math) education and celebrating science and math achievement in American schools. Morgan Freeman experience. Despite not having access to the millions of marketing Soledad O’Brien dollars required to make FIRST a household “brand,” the program has continued to grow each year at a blistering pace. …aND loudER Books, magazines, newspapers, cable TV, and the Web helped us create noise, too, with ongoing national coverage by Bloomberg, CNN, Popular Mechanics, In 2011, however, thanks to the fervent interest of major figures Popular Science, Wired, ESPN Magazine, WallStreetJournal.com, and more. Author Neal Bascomb brought the FIRST experience to life in his inspiring in government, the media, and mainstream entertainment, the book, The New Cool.Time Warner Cable incorporated “volume” of voices promoting FIRST... FIRST into its national “Connect A Million Minds™” initiative, featuring our FRC program in its TV show “It Ain’t Rocket Science.” The clamor of FIRST recognition continues to grow ...GOT TuRNED UP loud...VERY loud! louder every day. The continuing mainstream exposure is helping propel us toward our goal of making FIRST known and recognized around the globe. -

Pac Fundraising File

PAC FUNDRAISING RANKING FOR 2015-2016 CYCLE AS OF JULY 20, 2016 RANK NAME OF PAC AMOUNT AMOUNT RAISED IN RAISED AS OF 2015-2016 SAME POINT CYCLE (AS OF IN 2013-2014 JULY 20, 2016) CYCLE 1 HOUSE REPUBLICAN CAMPAIGN COMMITTEE $2,763,239 $2,460,213 2 MICHIGAN HOUSE DEMOCRATIC FUND $2,062,304 $1,837,991 3 SENATE REPUBLICAN CAMPAIGN COMMITTEE $1,894,958 $2,123,759 4 MICHIGAN SENATE DEMOCRATIC FUND $958,148 $839,493 5 BLUE CROSS BLUE SHIELD OF MICHIGAN PAC $933,166 $907,976 6 HEALTH PAC (MICHIGAN HEALTH AND HOSPITAL ASSOCIATION) $774,892 $696,557 7 REALTORS PAC OF MICHIGAN $757,622 $648,775 8 MICHIGAN BEER AND WINE WHOLESALERS PAC $745,683 $675,721 9 MICHIGAN REGIONAL COUNCIL OF CARPENTERS PAC $618,272 $505,313 10 GREAT LAKES EDUCATION PROJECT (GLEP) $590,050 $423,820 11 MICHIGAN PIPE TRADES ASSOCIATION (SUPER PAC) $579,369 $184,371 12 DTE ENERGY COMPANY PAC $554,578 $527,720 13 MICHIGAN EDUCATION ASSOCIATION PAC $519,184 $655,658 14 UAW MICHIGAN VOLUNTARY PAC $489,144 $1,000,000 15 MICHIGAN CHAMBER PAC $476,897 $422,929 16 BUSINESS LEADERS FOR MICHIGAN PAC II (SUPER PAC) $476,000 $515,000 17 MICHIGAN LABORERS POLITICAL LEAGUE $471,873 $284,560 18 MICHIGAN ASSOCIATION FOR JUSTICE (JUSTICE PAC) $460,175 $524,852 19 POWERING THE ECONOMY (DETROIT REGIONAL CHAMBER) (SUPER PAC) $438,314 $79,361 20 MOVING MICHIGAN FORWARD FUND II (SEN. ARLAN MEEKHOF) $437,661 $22,051 21 MICHIGAN BANKERS ASSOCIATION (MIBANKPAC) $369,571 $382,358 22 MOVING MICHIGAN FORWARD FUND (SEN. -

Point Source Water Contamination Module Was Originally Published in 2003 by the Advanced Technology Environmental and Energy Center (ATEEC)

From the POINT SOURCE Technology and Environmental Decision-Making WATER Series CONTAMINATION This 2017 version of the Point Source Water Contamination module was originally published in 2003 by the Advanced Technology Environmental and Energy Center (ATEEC). The module, part of the series Technology and Environmental Decision-Making: A critical-thinking approach to 7 environmental challenges, was initially developed by ATEEC and the Laboratory for Energy and Environment at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and funded by the National Science Foundation. The ATEEC project team has updated this version of the module and gratefully acknowledges the past and present contributions, assistance, and thoughtful critiques of this material provided by authors, content experts, and reviewers. These contributors do not, however, necessarily approve, disapprove, or endorse these modules. Any errors in the modules are the responsibility of ATEEC. Authors: Melonee Docherty, ATEEC Michael Beck, ATEEC Editor: Glo Hanne, ATEEC Copyright 2017, ATEEC This project was supported, in part, by the Advanced Technological Education Program at the National Science Foundation under Grant No. DUE #1204958. The information provided in this instructional material does not necessarily represent NSF policy. Cover image: Ground water monitoring wells, Cape Cod, MA. Credit: U.S. Geological Survey. Additional copies of this module can be downloaded from the ATEEC website. i Point Source Water Contamination Corroded pipes from Flint’s water distribution system. -

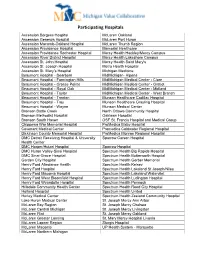

Participating Hospitals

Participating Hospitals Ascension Borgess Hospital McLaren Oakland Ascension Genesys Hospital McLaren Port Huron Ascension Macomb-Oakland Hospital McLaren Thumb Region Ascension Providence Hospital Memorial Healthcare Ascension Providence Rochester Hospital Mercy Health Hackley/Mercy Campus Ascension River District Hospital Mercy Health Lakeshore Campus Ascension St. John Hospital Mercy Health Saint Mary's Ascension St. Joseph Hospital Metro Health Hospital Ascension St. Mary’s Hospital Michigan Medicine Beaumont Hospital - Dearborn MidMichigan- Alpena Beaumont Hospital - Farmington Hills MidMichigan Medical Center - Clare Beaumont Hospital - Grosse Pointe MidMichigan Medical Center - Gratiot Beaumont Hospital - Royal Oak MidMichigan Medical Center - Midland Beaumont Hospital - Taylor MidMichigan Medical Center - West Branch Beaumont Hospital - Trenton Munson Healthcare Cadillac Hospital Beaumont Hospital - Troy Munson Healthcare Grayling Hospital Beaumont Hospital - Wayne Munson Medical Center Bronson Battle Creek North Ottawa Community Hospital Bronson Methodist Hospital Oaklawn Hospital Bronson South Haven OSF St. Francis Hospital and Medical Group Chippewa War Memorial Hospital ProMedica Bixby Hospital Covenant Medical Center Promedica Coldwater Regional Hospital Dickinson County Memorial Hospital ProMedica Monroe Regional Hospital DMC Detroit Receiving Hospital & University Sparrow Carson Hospital Health Center DMC Harper/Hutzel Hospital Sparrow Hospital DMC Huron Valley-Sinai Hospital Spectrum Health Big Rapids Hospital DMC Sinai-Grace -

Speakers of the House of Representatives, 1835-20171

SPEAKERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, 1835-20171 Representative County of Residence District Session Years Ezra Convis ............. Calhoun ............ Calhoun . 1835-1836 Charles W. Whipple ....... Wayne.............. Wayne .................. 1837 Kinsley S. Bingham........ Livingston ........... Livingston................ 1838-1839 Henry Acker............. Jackson ............. Jackson.................. 1840 Philo C. Fuller2 ........... Lenawee ............ Lenawee................. 1841 John Biddle ............. Wayne.............. Wayne .................. 1841 Kinsley S. Bingham........ Livingston ........... Livingston................ 1842 Robert McClelland ........ Monroe............. Monroe.................. 1843 Edwin H. Lothrop ......... Kalamazoo .......... Kalamazoo . 1844 Alfred H. Hanscom ........ Oakland ............ Oakland ................. 1845 Isaac E. Crary ............ Calhoun ............ Calhoun . 1846 George W. Peck .......... Livingston ........... Livingston................ 1847 Alexander W. Buel ........ Wayne.............. Wayne .................. 1848 Leander Chapman......... Jackson ............. Jackson.................. 1849 Silas G. Harris............ Ottawa ............. Ottawa/Kent .............. 1850 Jefferson G. Thurber ....... Monroe............. Monroe.................. 1851 Daniel G. Quackenboss .... Lenawee ............ 1st Lenawee .............. 1853 Cyrus Lovell ............. Ionia............... Ionia.................... 1855 Byron G. Stout ........... Oakland ............ 1st Oakland ............. -

SEARCH PROSPECTUS: Dean of the School of Management TABLE of CONTENTS

SEARCH PROSPECTUS: Dean of the School of Management TABLE OF CONTENTS OVERVIEW OF THE SEARCH 3 HISTORY OF KETTERING UNIVERSITY 4 THE COMMUNITY OF FLINT AND REGION 5 ABOUT KETTERING UNIVERSITY AND ACADEMIC LIFE 6 MISSION, VISION, VALUES AND PILLARS OF SUCCESS 6 SCHOOL LEADERSHIP AND GOVERNANCE 7 ACCOLADES AND POINTS OF PRIDE AT KETTERING UNIVERSITY 7 UNIVERSITY FINANCES 7 ACADEMIC PROGRAMS 7 INTERNATIONAL PROGRAMS AND OPPORTUNITIES 8 KETTERING UNIVERSITY ONLINE (KUO)/KETTERING GLOBAL 9 ACCREDITATION 9 THE SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT 9 STUDENTS AND ALUMNI 10 STUDENTS AND STUDENT LIFE 10 ALUMNI AND ALUMNI ACCOLADES 10 SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT FOR ACADEMIC AFFAIRS AND PROVOST 11 LEADERSHIP AGENDA FOR THE DEAN OF THE SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT 12 REQUIRED QUALIFICATIONS 12 DESIRED EXPERIENCE, KNOWLEDGE, AND ATTRIBUTES 13 PROCEDURES FOR NOMINATIONS AND APPLICATIONS 14 SEARCH PROSPECTUS: Dean of the School of Management 2 OVERVIEW OF THE SEARCH Kettering University, a private (nonprofit) co- It is an exciting time of energy, innovation, successes, educational institution in Flint, Michigan, invites challenges, and opportunities at Kettering University. nominations for and inquiries and applications The institution is a unique national leader in from individuals interested in a transformational experiential STEM and business education, integrating leadership opportunity as Dean of the School an intense curriculum with applied professional of Management. This position carries with it an experience. Students realize their potential and endowed chair title of Riopelle Endowed Chair of advance their ideas by combining theory and practice. Engineering Management. The Dean is expected to be an effective collaborative partner with Provost Dr. In June 2019 Kettering University announced a $150 James Z. -

Flint River Flood Mitigation Alternatives Saginaw County, Michigan

Draft Environmental Assessment Flint River Flood Mitigation Alternatives Saginaw County, Michigan Flint River Erosion Control Board FEMA-DR-1346-MI, HMGP Project No. A1346.53 April 2006 U.S. Department of Homeland Security FEMA Region V 536 South Clark Street, Sixth Floor Chicago, IL 60605 This document was prepared by URS Group, Inc. 200 Orchard Ridge Drive, Suite 101 Gaithersburg, MD 20878 Contract No. EMW-2000-CO-0246, Task Order No. 138. Job No. 15292488.00100 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Acronyms ........................................................................................................................................ iii Section 1 ONE Introduction........................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Project Authority..........................................................................................1 1.2 Project Location and Setting........................................................................1 1.3 Purpose and Need ........................................................................................2 Section 2 TWO Alternative Analysis .......................................................................................................... 3 2.1 Alternative 1 – No Action Alternative.........................................................3 2.2 Alternative 2 – Dike Reconstruction and Reservoir Construction (Proposed Action) ........................................................................................3 2.2.1 Project Segment -

EM **Quarterly Financial Report 7.15.2014

CITY OF FLINT OFFICE OF THE EMERGENCY MANA GER C Darnell Earley, ICMA-CM, MPA Emergency Manager July 14, 2014 Mr. R. Kevin Clinton, State Treasurer Michigan Department of Treasury Bureau of Local Government Services 4th floor Treasury building 430 West Allegan Street Lansing, MI 48922 Dear Mr. Clinton: I am attaching for your consideration the quarterly report of the Emergency Manager of the City of Flint as required by Section 9(5) of P.A. 436 of 2012. The report details activities for the period of April 1, 2014 through June 30, 2014. Respectfully submitted, Darnell Earley, ICMA-CM, MPA Emergency Manager Attachments cc: Wayne Workman, Deputy Treasurer Edward Koryzno, Bureau Director of Local Government Services Randall Byrne, Office of Fiscal Responsibility James Ananich, State Senator Woodrow Stanley, State Representative Phil Phelps, State Representative Dayne Walling, Mayor City of Flint City of Flint • 1101 S. Saginaw Street • Flint, Michigan 48502 www.cityofflint.com • (810) 766-7346 • Fax: (810) 766-7218 QUARTERLY REPORT TO THE STATE TREASURER REGARDING THE FINANCIAL CONDITION OF THE CITY OF FLINT July 15, 2014 This quarterly report covers the period from April 1, 2014 through June 30, 2014 and addresses the financial condition of the City of Flint. Per P.A. 436 Section 9 (MCL141.l549) requires that you submit quarterly reports to the State Treasurer with respect to the financial condition of your local government, secondly, a copy to each state senator and state representative who represents your local government. In addition, each quarterly report shall be posted on the local government’s website within 7 days after the report is submitted to the State Treasurer. -

Management Weaknesses Delayed Response to Flint Water Crisis

U.S. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL Ensuring clean and safe water Compliance with the law Management Weaknesses Delayed Response to Flint Water Crisis Report No. 18-P-0221 July 19, 2018 Report Contributors: Stacey Banks Charles Brunton Kathlene Butler Allison Dutton Tiffine Johnson-Davis Fred Light Jayne Lilienfeld-Jones Tim Roach Luke Stolz Danielle Tesch Khadija Walker Abbreviations CCT Corrosion Control Treatment CFR Code of Federal Regulations EPA U.S. Environmental Protection Agency FY Fiscal Year GAO U.S. Government Accountability Office LCR Lead and Copper Rule MDEQ Michigan Department of Environmental Quality OECA Office of Enforcement and Compliance Assurance OIG Office of Inspector General OW Office of Water ppb parts per billion PQL Practical Quantitation Limit PWSS Public Water System Supervision SDWA Safe Drinking Water Act Cover Photo: EPA Region 5 emergency response vehicle in Flint, Michigan. (EPA photo) Are you aware of fraud, waste or abuse in an EPA Office of Inspector General EPA program? 1200 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW (2410T) Washington, DC 20460 EPA Inspector General Hotline (202) 566-2391 1200 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW (2431T) www.epa.gov/oig Washington, DC 20460 (888) 546-8740 (202) 566-2599 (fax) [email protected] Subscribe to our Email Updates Follow us on Twitter @EPAoig Learn more about our OIG Hotline. Send us your Project Suggestions U.S. Environmental Protection Agency 18-P-0221 Office of Inspector General July 19, 2018 At a Glance Why We Did This Project Management Weaknesses -

Michigan Auto Project Progress Report - December 2000 I Inaugural Progress Report Michigan Automotive Pollution Prevention Project

A VOLUNTARY POLLUTION PREVENTION AND RESOURCE CONSERVATION PARTNERSHIP ADMINISTERED BY: Michigan Department of Environmental Quality Environmental Assistance Division DECEMBER, 2000: 1st ISSUE John Engler, Governor • Russell J. Harding, Director www.deq.state.mi.us ACKNOWLEDGMENTS DaimlerChrysler Corporation, Ford Motor Company, General Motors Corporation and the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) thank the Auto Project Stakeholder Group members for providing advice to the Auto Project partners and facilitating public information exchange. The Auto Companies and MDEQ also acknowledge the guidance and counsel provided by the US EPA Region V. CONTACTS FOR ADDITIONAL INFORMATION For information regarding the Michigan Automotive Pollution Prevention Project Progress Report, contact DaimlerChrysler, Ford, or General Motors at the addresses listed below or the Environmental Assistance Division of the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality at 1-800-662-9278. DaimlerChrysler Ford Doug Orf, CIMS 482-00-51 Sue Rokosz DaimlerChrysler Corporation Ford Motor Company 800 Chrysler Drive One Parklane Blvd., Suite 1400 Auburn Hills, MI 48326-2757 Dearborn, MI 48126 [email protected] [email protected] General Motors MDEQ Sandra Brewer, 482-303-300 Anita Singh Welch General Motors Corporation Environmental Assistance Division 465 W. Milwaukee Ave. Michigan Department of Environmental Quality Detroit, MI 48202 P.O. Box 30457 [email protected] Lansing, MI 48909 [email protected] Michigan Auto Project Progress Report - December 2000 i Inaugural Progress Report Michigan Automotive Pollution Prevention Project TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Foreward iv I. Executive Summary Project Overview 1 Activities and Accomplishments 4 Focus on Michigan 11 Auto Company Profiles II. DaimlerChrysler Corporation Project Status 12 Activities and Accomplishments 14 Focus on Michigan 16 III.