Area Handbook for Uruguay. INSTITUTION American Univ., Washington, D.C.Foreign Area Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La República Perdida

1 UNIVERSIDAD DE LA REPÚBLICA FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS SOCIALES INSTITUTO DE CIENCIA POLÍTICA Maestría en Ciencia Política LA REPÚBLICA PERDIDA Democracia y ciudadanía en el discurso político de los batllistas de la lista quince. 1946-1972 Pablo Ferreira Rodríguez Tutor: Mag. Jaime Yaffé diciembre/2013 2 ÍNDICE Índice....................................................................................................................................................2 I- Introducción ....................................................................................................................................4 1. Objetivo de la .tesis ...................................................................................................................5 2. La hipótesis ................................................................................................................................6 3. Delimitación temporal, estructura de la tesis y periodización....................................................9 4. Apuntes sobre la metodología...................................................................................................11 4.1 La trayectoria dinámica de los conceptos políticos..........................................................11 4.2. Discurso político y acción política..................................................................................12 4.3. Escalas de observación....................................................................................................13 4.4. Actores y fuentes..............................................................................................................14 -

El Herrerismo Como Factor 'Amortiguador' De La Política Exterior

UNIVERSIDAD DE LA REPÚBLICA FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS SOCIALES DEPARTAMENTO DE CIENCIA POLÍTICA Licenciatura en Ciencia Política El herrerismo como factor ‘amortiguador’ de la política exterior uruguaya José Carlos Castro Meny Tutores: Romeo Pérez Antón, Adolfo Garcé 1 _________________________________________________ EL HERRERISMO COMO FACTOR ‘AMORTIGUADOR’ DE LA POLÍTICA EXTERIOR URUGUAYA __________________________________________ CASTRO MENY José Carlos Tutor(es): Dr. Romeo Pérez Antón, Dr. Adolfo Garcé _____________________________________________________________ UDELAR // Facultad de Ciencias Sociales Monografía de Grado de la Licenciatura en Ciencia Política _____________________________________________________________ Dedicado a mis compañeros de estudio, mi deseo y esperanza para que disfruten de “un mundo de mayor libertad y verdadera justicia” (Haedo 1969: dedicatoria). _____________________________________________________________ Así como se nos ha pensado como una ‘sociedad amortiguadora’ -así definida por, y a partir del análisis de Carlos Real de Azúa (1)- del mismo modo pretendemos hablar de un ’herrerismo amortiguador’ respecto del giro de la inserción de la política exterior uruguaya hacia el panamericanismo. Durante el período de ascenso como potencia de Estados Unidos de América, que devendrá en hegemónica, nuestro país bajo la batuta del batllismo (Baltasar Brum (2), Alberto Guani (3)) inclinará la balanza de nuestra diplomacia como afín a la de la potencia emergente. Al mismo tiempo, uno de nuestros dos vecinos, la República Argentina, mantendrá una actitud de distancia y neutralidad. Un mayor apego a las posiciones tradicionales en materia de política exterior. A diferencia de Brasil, cuya política exterior busca consolidarse como potencia regional sub- hegemónica, en detrimento de la pretensión de la República Argentina, y con el paraguas de sus acuerdos con los Estados Unidos de América. -

Complete Issue More Information About This Article Journal's Webpage in Redalyc.Org Basso, C.; Cibils-Stewart, X. Foundations An

Agrociencia Uruguay ISSN: 1510-0839 ISSN: 2301-1548 [email protected] Universidad de la República Uruguay Basso, C.; Cibils-Stewart, X. Foundations and developments of pest management in Uruguay: a review of the lessons and challenges Agrociencia Uruguay, vol. 24, no. 2, 2020, July-December, pp. 1-28 Universidad de la República Uruguay DOI: https://doi.org/10.31285/AGRO.24.409 Complete issue More information about this article Journal's webpage in redalyc.org Agrociencia Uruguay 2020 | Volume 24 | Number 2 | Article 409 DOI: 10.31285/AGRO.24.409 ISSN 2301-1548 Foundations and developments of pest management in Uruguay Editor a review of the lessons and challenges Martín Bollazzi Universidad de la República, Montevideo, Uruguay. Cimientos y desarrollo del manejo de Correspondence plagas en Uruguay César Basso, [email protected] una revisión de las lecciones y los desafíos Received 08 Sep 2020 Accepted 01 Oct 2020 Fundamentos e desenvolvimento do Published 13 Oct 2020 manejo de pragas no Uruguai Citation Basso C, Cibils-Stewart X. Foundations and developments uma revisão das lições e desafios of pest management in Uruguay: a review of the lessons and challenges. Agrociencia Uruguay [Internet]. Basso, C. 1; Cibils-Stewart, X. 2 2020 [cited dd mmm yyyy];24(2):409. Available from: http://agrocienciauruguay. uy/ojs/index.php/agrocien- 1Universidad de la República, Facultad de Agronomía, Unidad de cia/article/view/409 Entomología, Montevideo, Uruguay. 2Instituto Nacional de Investigación Agropecuaria (INIA), Programa Nacional de Investigación en Pasturas y Forrajeras, Entomología, Protección Vegetal, Colonia, Uruguay. History of pest management in Uruguay Abstract FAO has proclaimed 2020 as the “International Year of Plant Health”. -

Hugo Cores Former Guerrillas in Power:Advances, Setbacks And

Hugo Cores Former Guerrillas in Power: Advances, Setbacks and Contradictions in the Uruguayan Frente Amplio For over 135 years, Uruguayan politics was essen- tially a two party system. There had been other “small parties” including socialist parties, commu- nist parties or those inspired by Christian groups but all of them garnered little electoral support. Within the two principal political parties that competed for power, however, there were factions within each that could be considered to a greater or lesser extent progressive, anti-imperialist, and/or committed to some kind of vision of social justice. For the most part, the working class vote tended to gravitate towards these progressive wings within the domi- nant parties. The Twentieth Century history of the Uruguayan left would have been very distinct had pragmatism prevailed, an attitude that was later called the logic of incidencia by leaders of the Independent Batllist Faction (CBI – Corriente Batllista Independiente). Indeed, what sense did it make during the 1920s, 30s, 40s and 50s to be a socialist, communist, or Christian Democrat when if all taken together, they failed to reach even 10% of the vote? When the “theorists” of the CBI spoke of the “logic of incidencia, they referred to the idea that voting and cultivating an accumulation of left forces within the traditional political parties was a viable strategy to 222 • Hugo Cores have an organised impact upon the state apparatus, establishing positions of influence from within. The intent of the CBI itself to pursue such a strategy ultimately failed and disintegrated or became absorbed within the ranks of political support given to the Colorado Party of Sanguinetti.1 To remain outside of the traditional political parties, in contrast, meant that the opposition would be deprived of incidencia. -

1 María Eugenia Jung U

Vol. 13, No. 2, Winter 2016, 172-211 Una universidad para Salto: de demanda localista a la agenda de los grupos de derecha radical (1968-1970)1 María Eugenia Jung Universidad de la República Introducción La instalación de una universidad “propia” fue largamente acariciada por variados sectores de la sociedad salteña, que la concibieron como otra forma de enfrentar el centralismo montevideano y dinamizar su propio desarrollo. Desde mediados de los años 40 hubo varias iniciativas al respecto, promovidas por organizaciones civiles, asociaciones profesionales y agrupaciones de padres, docentes y estudiantes con el apoyo de las autoridades municipales. Como resultado en noviembre de 1948 se colocó la piedra fundamental y se procedió a la posesión simbólica de los terrenos donde se pensaba instalar la futura Universidad del Norte (UN) y casi una década más tarde, en 1957, tras la intensa movilización de alumnos de bachillerato del Liceo Departamental, profesores y padres, se instalaron cursos de primer año de Derecho y Notariado de la Universidad de la República (UDELAR), lo que fue concebido en ámbitos locales como un primer paso en la creación de la UN. En diciembre de 1966, el diputado 1 Este artículo es una versión de mi tesis de maestría en Ciencias Humanas, opción Historia Rioplatense. Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de la Educación—UDELAR. La educación superior entre el reclamo localista y la ofensiva derechista. El Movimiento pro Universidad del Norte de Salto (1968- 1973), defendida y aprobada en 2014. Una universidad para Salto 173 salteño Martín Boada presentó a la Cámara de Representantes un proyecto de ley para su instalación que no prosperó2. -

List of Presidents of Uruguay

SNo Name Took office Left office Political party 1 Fructuoso Rivera November 6, 1830 October 24, 1834 Colorado 2 Carlos Anaya October 24, 1834 March 1, 1835 Colorado 3 Manuel Oribe March 1, 1835 October 24, 1838 National 4 Gabriel Antonio Pereira October 24, 1838 March 1, 1839 Colorado 5 Fructuoso Rivera March 1, 1839 March 1, 1843 Colorado 6 Manuel Oribe February 16, 1843 October 8, 1851 National 7 Joaquín Suárez March 1, 1843 February 15, 1852 Colorado 8 Bernardo Berro February 15, 1852 March 1, 1852 National 9 Juan Francisco Giró March 1, 1852 September 25, 1853 National 10 Venancio Flores September 25, 1853 March 12, 1854 Colorado 11 Juan Antonio Lavalleja September 25, 1853 October 22, 1853 Independent 12 Fructuoso Rivera September 25, 1853 January 13, 1854 Colorado 13 Venancio Flores March 12, 1854 August 29, 1855 Colorado 14 Luis Lamas August 29, 1855 September 10, 1855 National 15 Manuel Basilio Bustamante September 10, 1855 February 15, 1856 Colorado 16 José María Plá February 15, 1856 March 1, 1856 Colorado 17 Gabriel Antonio Pereira March 1, 1856 March 1, 1860 Colorado 18 Bernardo Berro March 1, 1860 March 1, 1864 National 19 Atanasio Aguirre March 1, 1864 February 15, 1865 National 20 Tomás Villalba February 15, 1865 February 20, 1865 National 21 Venancio Flores February 20, 1865 February 15, 1868 Colorado 22 Pedro Varela February 15, 1868 March 1, 1868 Colorado 23 Lorenzo Batlle y Grau March 1, 1868 March 1, 1872 Colorado 24 Tomás Gomensoro Albín March 1, 1872 March 1, 1873 Colorado 25 José Eugenio Ellauri March 1, 1873 January -

Jorge Luis Batlle Ibáñez

Jorge Luis Batlle Ibáñez Uruguay, Presidente de la República Duración del mandato: 01 de Marzo de 2000 - de de Nacimiento: Montevideo, departamento de Montevideo, 25 de Octubre de 1927 Partido político: PC Profesión : Periodista ResumenJorge Luis Batlle Ibáñez es el heredero de una de las más célebres dinastías políticas de Uruguay. Siendo en origen una familia catalana emigrada desde Sitges, población de mar cercana a Barcelona, al país platense a principios del siglo XIX, antes de la independencia de España en 1830, los Batlle han estado en la médula del Partido Colorado (PC), histórica formación de tradición liberal y progresista, si bien muchas veces escorada a la derecha. http://www.cidob.org 1 of 14 Biografía 1. Un dirigente de casta del Partido Colorado 2. Otras tres apuestas presidenciales tras la restauración de la democracia 3. Una Administración marcada por la crisis económica 4. La debacle financiera de 2002 5. Pérdida de la iniciativa política hasta el final del mandato 1. Un dirigente de casta del Partido Colorado Junto con su rival, el, en origen, más conservador Partido Nacional (PN), también llamado Blanco, el PC conformó un duopolio por el que los dos se alternaron irregularmente en el poder durante 170 años, aunque los colorados gobernaron mucho más tiempo que los blancos; precisamente, el período presidencial de Jorge Batlle, entre 2000 y 2005, marcó el final de esta larguísima supremacía desigualmente compartida. Así, su tío-abuelo fue José Pablo Batlle Ordóñez (1856-1929), quien ocupara la Presidencia de la República tres veces, en 1899, en 1903-1907 y en 1911-1915; a su vez, José Batlle era hijo de Lorenzo Cristóbal Batlle Grau (1810-1887), presidente en 1868-1872. -

Conflictos Sociales Y Guerras De Independencia En La Provincia Cisplatina/Oriental, 1820-1830

X Jornadas Interescuelas/Departamentos de Historia. Escuela de Historia de la Facultad de Humanidades y Artes, Universidad Nacional del Rosario. Departamento de Historia de la Facultad de Ciencias de la Educación, Universidad Nacional del Litoral, Rosario, 2005. Conflictos sociales y guerras de independencia en la Provincia Cisplatina/Oriental, 1820-1830. Enfrentamientos étnicos: de la alianza al exterminio. Frega Ana. Cita: Frega Ana (2005). Conflictos sociales y guerras de independencia en la Provincia Cisplatina/Oriental, 1820-1830. Enfrentamientos étnicos: de la alianza al exterminio. X Jornadas Interescuelas/Departamentos de Historia. Escuela de Historia de la Facultad de Humanidades y Artes, Universidad Nacional del Rosario. Departamento de Historia de la Facultad de Ciencias de la Educación, Universidad Nacional del Litoral, Rosario. Dirección estable: https://www.aacademica.org/000-006/16 Acta Académica es un proyecto académico sin fines de lucro enmarcado en la iniciativa de acceso abierto. Acta Académica fue creado para facilitar a investigadores de todo el mundo el compartir su producción académica. Para crear un perfil gratuitamente o acceder a otros trabajos visite: https://www.aacademica.org. Xº JORNADAS INTERESCUELAS / DEPARTAMENTOS DE HISTORIA Rosario, 20 al 23 de septiembre de 2005 Título: Conflictos sociales y guerras de independencia en la Provincia Cisplatina/Oriental, 1820-1830. Enfrentamientos étnicos: de la alianza al exterminio Mesa Temática Nº 2: Conflictividad, insurgencia y revolución en América del Sur. 1800-1830 Pertenencia institucional: Universidad de la República, Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de la Educación, Departamento de Historia del Uruguay Autora: Frega, Ana. Profesora Agregada del Dpto. de Historia del Uruguay. Dirección laboral: Magallanes 1577, teléfono (+5982) 408 1838, fax (+5982) 408 4303 Correo electrónico: [email protected] 1 Conflictos sociales y guerras de independencia en la Provincia Cisplatina/Oriental, 1820-1830. -

Essential Facts About the League of Nations

■(/IS. S' ESSENTIAL FACTS ABOUT THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS GENEVA 1937 1. New Buildings of the League 2. International Labour Office 3. Former Buildings of the League (1920-1935) ESSENTIAL FACTS ABOUT THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS EIGHTH EDITION (REVISED) GEN EVA 1937 INFORMATION SECTION r NOTE This publication, which has been prepared by the Informa- tion Section of the League of Nations Secretariat, is not to be regarded as an official document for which the League of Nations is responsible. Passages from the text of the Covenant of the League of Nations appear in heavy type. The complete text of the Covenant is at the beginning of this book. The information herein contained has been revised down to December 31st, 1936. What is public opinion? It is an old but very useful cloak which diplomats and Ministers for Foreign Affairs like to draw around them when their disagreements threaten to embarrass their personal relations. But it is much more than that. It is essentially a feeling which everyone shares. It may at times be coloured by heroism or enthusiasm, dignity or resignation. But some such common feeling there must be, if modern organised societies are to accept the laws and restraints, the surrender of wealth and the possible surrender of life, which are necessary to their preservation. The experience and memories of the last war and of the severe economic depression which followed upon it have focused public opinion on foreign policy. The people of every country find their everyday life affected by variations in other countries. More than this, the view which other peoples take of peace and war, their stability or " dynamism ” (as it is called nowadays) may in every country have the effect of increasing taxation through expenditure on armaments and of endangering the lives of millions. -

University of California Santa Cruz Marxism

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ MARXISM AND CONSTITUENT POWER IN LATIN AMERICA: THEORY AND HISTORY FROM THE MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY THROUGH THE PINK TIDE A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in HISTORY OF CONSCIOUSNESS with an emphasis in POLITICS by Robert Cavooris December 2019 The dissertation of Robert Cavooris is approved: _______________________________________ Robert Meister, Chair _______________________________________ Guillermo Delgado-P. _______________________________________ Juan Poblete _______________________________________ Megan Thomas _________________________________________ Quentin Williams Acting Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Robert Cavooris, 2019. All rights reserved. Table of Contents Abstract iv Acknowledgements and Dedication vi Preface x Introduction 1 Chapter 1 41 Intellectuals and Political Strategy: Hegemony, Posthegemony, and Post-Marxist Theory in Latin America Chapter 2 83 Constituent Power and Capitalism in the Works of René Zavaleta Mercado Chapter 3 137 Bolivian Insurgency and the Early Work of Comuna Chapter 4 204 Potentials and Limitations of the Bolivian ‘Process of Change’ Conclusions 261 Appendix: List of Major Works by Comuna (1999–2011) 266 Bibliography 271 iii Abstract Marxism and Constituent Power in Latin America: Theory and History from the Mid-Twentieth Century through The Pink Tide Robert Cavooris Throughout the history of Marxist theory and practice in Latin America, certain questions recur. What is the relationship between political and social revolution? How can state institutions serve as tools for political change? What is the basis for mass collective political agency? And how can intellectual work contribute to broader emancipatory political movements? Through textual and historical analysis, this dissertation examines how Latin American intellectuals and political actors have reframed and answered these questions in changing historical circumstances. -

INTELLECTUALS and POLITICS in the URUGUAYAN CRISIS, 1960-1973 This Thesis Is Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements

INTELLECTUALS AND POLITICS IN THE URUGUAYAN CRISIS, 1960-1973 This thesis is submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Spanish and Latin American Studies at the University of New South Wales 1998 And when words are felt to be deceptive, only violence remains. We are on its threshold. We belong, then, to a generation which experiences Uruguay itself as a problem, which does not accept what has already been done and which, alienated from the usual saving rituals, has been compelled to radically ask itself: What the hell is all this? Alberto Methol Ferré [1958] ‘There’s nothing like Uruguay’ was one politician and journalist’s favourite catchphrase. It started out as the pride and joy of a vision of the nation and ended up as the advertising jingle for a brand of cooking oil. Sic transit gloria mundi. Carlos Martínez Moreno [1971] In this exercise of critical analysis with no available space to create a distance between living and thinking, between the duties of civic involvement and the will towards lucidity and objectivity, the dangers of confusing reality and desire, forecast and hope, are enormous. How can one deny it? However, there are also facts. Carlos Real de Azúa [1971] i Acknowledgments ii Note on references in footnotes and bibliography iii Preface iv Introduction: Intellectuals, Politics and an Unanswered Question about Uruguay 1 PART ONE - NATION AND DIALOGUE: WRITERS, ESSAYS AND THE READING PUBLIC 22 Chapter One: The Writer, the Book and the Nation in Uruguay, 1960-1973 -

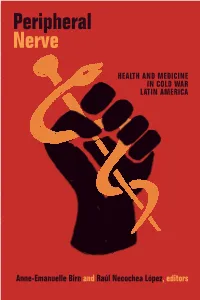

Peripheral Nerve

Peripheral Nerve HEALTH AND MEDICINE IN COLD WAR LATIN AMERICA Anne-Emanuelle Birn and Raúl Necochea López, editors AMERICAN ENCOUNTERS/GLOBAL INTERACTIONS A Series edited by Gilbert M. Joseph and Penny Von Eschen The series aims to stimulate critical perspectives and fresh interpretive frameworks for scholarship on the history of the imposing global presence of the United States. Its pri- mary concerns include the deployment and contestation of power, the construction and deconstruction of cultural and po liti cal borders, the fl uid meaning of intercultural encoun- ters, and the complex interplay between the global and the local. American Encounters seeks to strengthen dialogue and collaboration between historian of U.S. international relations and area studies specialists. The series encourages scholarship based on multi- archive historical research. At the same time, it supports a recognition of the repre sen ta tional character of all stories about the past and promotes critical inquiry into issues of subjectivity and narrative. In the pro cess, American En- counters strives to understand the context in which mean- ings related to nations, cultures, and po liti cal economy are continually produced, challenged, and reshaped. Peripheral Nerve HEALTH AND MEDICINE IN COLD WAR LATIN AMER ICA Anne- Emanuelle Birn and Raúl Necochea López DUKE UNIVERSITY PRESS DURHAM AND LONDON 2020 © 2020 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Drew Sisk Typeset in Portrait Text, Folio, and Rockwell by Westchester Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Birn, Anne- Emanuelle, [date].